Updated February 1, 2026

The Tragedy of the Six Marys – Sun Myung Moon is the real Satan!!

45

Fleeing South to Escape the War

This chapter has been newly translated from the Korean. All the photos from the book, with additions, are included. The Japanese text can be found HERE. The Korean HERE.

▲ Seoul city in ruins during the Korean War. (September 1950)

47

From Pyongyang to Seoul

Pak Chung-hwa’s ankle bone fractured by thugs

Avoiding air raids, sometimes running along mountain paths and sometimes sleeping on the way, I arrived in Pyongyang three days later. After reuniting with my family, who had taken refuge at a church to escape the bombing, I went the next day to look for the house of the woman Kim Chong-hwa, but I could not find it. Around that time, the South Korean army was being pushed back by the North Korean army, and on August 18, 1950, the Korean government had moved to Busan.

The city of Pyongyang, controlled by the communist government of the North, was overflowing with an atmosphere of victory, but on September 15 the UN forces landed at Incheon, striking the rear of the North Korean army, and the tide of the war was reversed. The advance of the UN forces was swift, and by late September the South Korean and UN forces entered Pyongyang.

One day around that time, I was surrounded by a group of lawless men who called themselves a security unit. They were street thugs who welcomed the North when the North came and wagged their tails at the South and embraced those forces when they arrived.

“You were a battalion commander in the North Korean army, a real Communist Party member, so we’ll kill you. Die!” Several of them rushed at me and struck my leg with a hammer. My ankle bone was broken, and I was unable to move. By chance, I was rescued by a jeep of the South Korean military police that was passing by and was taken into custody for questioning, but when it was discovered that I had been imprisoned for dereliction of duty, I was released.

At one point, thinking that I might be killed in such a place, I had resolved myself to death, and I even found myself giving a hollow laugh, thinking, “You really never know what brings good fortune to a person.” Among those who remained in custody at that time, it seems that all of the serious offenders were executed by firing squad.

Because of the war, there were no hospitals in the city that were functioning properly anywhere. As a fifth-dan black belt in judo, I had no choice but to obtain suitable medicine from a pharmacy and take it, and for my broken ankle I applied an emergency measure by placing a wooden splint against it and binding it tightly.

48

Reunion with Yong Myung Moon (文龍明)

On October 27, Kim Won-pil and Moon Jeong-bin came to find me. They said that Teacher Moon had been released from prison and had arrived in Pyongyang on October 24, and since he was looking for me, they had come to take me to him. It was all so sudden that I was filled with joy and gladness, and I could hardly get any words out.

I was loaded onto a handcart and taken to the house of Ok Se-hyun, which was located on a gentle hillside. There, Teacher Moon greeted me warmly. At that moment, Teacher Moon and I clasped hands and burst into tears. Having been freed when the Heungnam Prison was liberated by the UN forces on October 14, Teacher Moon seems to have walked all the way to Pyongyang over the course of ten days.

Ok Se-hyun’s home was a Japanese-style house with a site measuring several hundred pyeong and several buildings standing on it, so it was certainly the home of a very wealthy family. Ok Se-hyun, her daughters Jeong-ae and Jeong-sun, Teacher Moon, Kim Won-pil, Moon Jeong-bin, and I, seven people in all, lived together like one family.

After about a week, the entire family of Woo Ha-seop, Ok Se-hyun’s husband, returned from Seoul, where they had evacuated, so we had no choice but to vacate the rooms we had been using. After discussing the matter, everyone decided to rent a room in a place called Seoseong-ri, and we moved there the next day. Teacher Moon, Kim Won-pil, Moon Jeong-bin, and I, the four of us, lived together.

During that time, Teacher Moon went around visiting acquaintances to check on their well-being, and he had Kim Won-pil notify people of his release from prison. Then, in Pyongyang, on December 2, 1950, an evacuation order was issued to all citizens throughout the city. This was because large numbers of Chinese troops had been deployed and were surging in like a massive human wave, forcing the South Korean and UN forces to withdraw temporarily.

At one point, the advance of the North Korean People’s Army, which had been driven all the way to the northernmost reaches of the Korean Peninsula, together with the Chinese Volunteer Army supporting it (which entered the war on October 25), seems to have been unexpectedly rapid. That night, a munitions depot not far away was bombed, and explosions continued all night long, so that we could not get even a moment of sleep.

49

Leaving my family in the North and following Teacher Moon

We decided to evacuate south. However, since my leg fracture had not yet healed and I could not walk, we decided to bring a bicycle from my older sister’s house in Sangsu-guri. I would ride it, and Kim Won-pil would push from behind.

We departed Pyongyang around 10 a.m. on December 4, 1950. Although it was winter, it was not yet terribly cold, so there were relatively few obstacles to evacuation. On the way, we planned to stop by my family home in Daedong County.

When we arrived at my home, my family welcomed us warmly. That I should set out for the South with an injured leg at such a difficult time met with strong opposition from the entire family, who said it was “utterly reckless.”

My nephew Jeong-geun desperately tried to stop me, saying, “Uncle, how can you even think of evacuating south with that leg?” Teacher Moon tried to persuade my family, explaining, “Although Pyongyang lies before our eyes, in the North it has become impossible to accomplish our purpose. We must, according to Heaven’s will, first go south.”

Bound by the promise between men that we had made in prison, I had already decided in my heart that I must go south together with Teacher Moon. After bidding farewell to my mother, who was already eighty years old, I entrusted family matters to my wife. At that moment, my eldest daughter, Hyo-sun, came forward in tears and said, “I will go south with Father too and take care of him,” but Teacher Moon dissuaded her. Teacher Moon also urged Moon Jeong-bin, who had come with us from Heungnam, to wait and come south later when the opportunity arose, and so they remained at my home.

Since Chinese Communist forces were surging forward like a flood behind Pyongyang, we thought that the only way to survive was to cross the Taedong River as quickly as possible. So we asked Jeong-geun for help, and that night we were able to cross by boat to Hyo-nam-ri in Namchung-myeon.

That night we stayed at my older sister’s house nearby. Many villagers who were trying to evacuate to the South had gathered there. The next morning, December 5, my sister loaded the food she had prepared onto the bicycle. I rode it while Kim Won-pil pushed from behind as we set out.

My sister thought Teacher Moon was a pastor, and the image of her bowing her head and saying, “Pastor, please take good care of my younger brother,” remains vividly in my memory even now. (After that, for forty-three years, meeting my family faded away like a vanishing dream, and I often wondered what had become of my wife and five children.)

50

The man who promised to stay together until death

The road southward was overflowing with people. The refugees were each holding hands, and truly tens of thousands of people were slowly walking south, southward. We passed through Yeokpo and entered Yongyeon-myeon, finally arriving at Gahak-ri around noon.

From the west, we could hear the sounds of bombing raids by aircraft and gunfire. The day was overcast, so although the sun had not yet set, it was already dark as if it had already gone down. At Teacher Moon’s direction, saying that we should give up going any farther that day and find a place to rest, we entered a nearby village and went into a farmhouse at the entrance. It seemed that no one was living there. The household goods were still there, but it appeared that the owner had fled south, because when we went into the kitchen, not only rice but also kimchi, soy sauce, and soybean paste were all left behind.

▲ Hordes of refugees fleeing from the North to the South during the war.

It truly felt as if the last day of humanity had come. What would become of this world from now on? Furniture, household goods, clothing, everything was left just as it was, yet only the families seemed to have evaporated. Seeing the scene of the first house we entered to rest during the evacuation made me think about many things.

Won-pil prepared the evening meal and brought it in. It was a simple table set with white rice and watery kimchi. We offered a prayer of thanks and ate. Teacher Moon said, “Chung-hwa’s leg is broken, so he is suffering, but it will heal soon. You will be able to walk freely again, so put your mind at ease.”

And perhaps because I looked lonely, thinking of my family, he encouraged me, saying, “We are going south now to create a new history. This is not merely a road of evacuation. We intended to create a new history in this world centered on Pyongyang, but because they sent me to prison, it came to nothing. We will do it again in the South.”

We spread out the quilts that had been neatly folded and placed on top of the rice chest and lay down, but no matter how hard I tried, I could not fall asleep. Won-pil, perhaps exhausted, fell asleep right away, but Teacher Moon also seemed unable to sleep for quite some time. Was he thinking about plans from now on?

“From now on, for our entire lives, Moon Yong-myung (his real name) and Pak Chung-hwa will share hardship and joy together and live together forever.” Because we had sworn this oath to each other in prison, was it not for this reason that I left my beloved hometown, parted from my loving family—my parents, elder brother, and my wife and five children (the eldest son aged seventeen, the second son fifteen, the third son thirteen, the eldest daughter ten, and the youngest son five)—and dragged my broken leg all the way here?

I entrusted my entire life to Teacher Moon, whom I believed to be the returning Messiah.

It seems I too was utterly exhausted. Before I knew it, I fell asleep, and when I awoke, the morning sun was already rising.

On the evacuation route, our clothing was as follows: Teacher Moon wore white silk trousers, rubber shoes, a black overcoat, and on his head a black anti-communist hood reminiscent of the final days of the Japanese colonial period. It gave the impression of something like the dangui ceremonial jackets worn by women in the feudal era, with only the front of the face visible. Not only his outward appearance but also his voice was like that of a woman, to the point that one could mistake him for an actual woman. As for me, I wore work clothes top and bottom, Japanese army boots, and a yellowish winter cap on my head. With baggage loaded onto a bright foreign-made bicycle, I, with my injured leg, sat astride it holding the handlebars, while Won-pil and Teacher Moon took turns pushing from behind. That sight must have looked rather strange.

52

A desperate and grueling refugee journey

If one took the main roads heading south, the route would have been relatively flat and easy, but military police were stationed here and there, restricting passage. In the end, the only routes the evacuees could use were narrow side roads with many ups and downs. As the days passed, the number of evacuees increased, and truly, like a flood of humanity, they overflowed the narrow roads. There was no guarantee whatsoever that simply going south would ensure survival, yet still, with some kind of hope, people continued heading south.

When leaving Pyongyang, we had set out on the evacuation road carrying bundles of clothing and household goods on our backs, but as the days went by, those loads gradually diminished. Walking continuously, our legs hurt and we grew exhausted, and items that were not particularly important were repeatedly discarded. By the time about twenty days of evacuation had passed, our baggage had almost completely dwindled away. With fatigue piling up in our bodies, the cold of midwinter was felt all the more keenly. Whenever we spotted a place where the snow had melted on the grass, suggesting warmth, we did not hesitate to rest, walking on again little by little. Even so, worries about sleeping places and meals were not especially severe.

That day as well, we decided to look for lodging a little early and rest, and entered a nearby village. When we went into one house, it looked like a fairly well-to-do household, but there was no one there. As before, the household goods and food had been left behind. After choosing a room and resting for quite some time, Won-pil prepared supper, and the three of us ate together. With my injured leg, I had no confidence that I could make it all the way to Busan like this. Mixed in with the steadily increasing number of evacuees, we continued heading south, southward.

Along the way, near Gwangju, there was a steep mountain pass with a slope of nearly 30 degrees. The pass was about 150 meters long, a stretch where it was impossible to push the bicycle up. No matter how hard Won-pil pushed while I sat on the bicycle, we could not climb it easily. Just when it seemed we had gone up a little, the bicycle would slip and tumble backward.

All around us the evacuees were packed tightly together, each one trying to get ahead of the others. Thinking that at this rate we would never be able to move forward, and believing that it would not do for Teacher Moon and Won-pil to be unable to go south because of me, I said to Teacher Moon,

“I can’t go on anymore. Leave me here and go ahead. Whatever happens to me here, I will accept my fate.”

At that, Teacher Moon grew angry and said,

“Didn’t you and I promise to stay together even unto death? Whatever happens from now on, let us live believing in God. Do not worry!”

He told Won-pil to take hold of the bicycle, and then carried me on his back and crossed over the pass. Deeply moved, I resolved once again to trust Teacher Moon and follow him.

54

Finally arriving in Seoul

After that, the three of us endured severe hardships on our way south: we witnessed many people being killed by strafing from UN fighter planes, carried out on the basis of information that communist troops were mixed among the evacuees heading south; we endured unbearable difficulties and passed through Sariwon, Haseong, Donghaeju, Cheongdan, Naeseong, Yongmaedo, Yeongyang, Toseong, and Jangseo, crossed the Imjin River to enter the South, passed Mapo, and headed toward Seoul.

On December 27, amid heavy falling snow, slipping and tumbling as we crossed the frozen Han River, the three of us arrived in the Seoul we had seen in our dreams after 24 days. First, we visited the home of a person surnamed Gwak in Heukseok-dong, Yeongdeungpo District. However, the man named Gwak, an old friend of Teacher Moon, had already evacuated toward Busan, and the house was empty.

The house was a two-story Western-style building, with all the household furnishings left as they were. With no other choice, we stayed in this empty house for some time. Seoul was Teacher Moon’s second hometown, where he had lived since his student days and experienced many things in terms of faith.

From there, Teacher Moon went to visit an elderly woman named Lee Gi-bong, at whose place he had boarded for a while after returning from his studies in Japan. But for some reason, she did not greet him warmly. After that, he went to see several other old friends, but whether they found Teacher Moon’s appearance strange, or whether we looked like beggars, they did not treat us kindly.

At that time, however, the citizens of Seoul were being rounded up by members of the National Defense Corps. Because my leg was disabled, I was not taken, but Teacher Moon and Won-pil were taken away unconditionally. The three of us had crossed the line of death and barely reached Seoul from Pyongyang, and now what was this? Left alone by myself and worried about what would happen next, there was nothing I could do.

For me, Seoul was an unfamiliar place, with not a single person I knew. Moreover, it was wartime. Even when Teacher Moon went to see people he knew, they did not treat him kindly, so even if someone like me were to visit them, there was no reason they would show me any sympathy. What, then, was I supposed to do from now on? No matter how much I thought about it, nothing came to mind. There was nothing to do but trust Teacher Moon and wait.

Fortunately, Teacher Moon and Won-pil were judged unfit during the National Defense Corps’ internal screening and returned, and the three of us once again lived together at Mr. Gwak’s house in Heukseok-dong.

With the new year, on January 2, 1951, an evacuation order was issued throughout Seoul. The communist forces had advanced close by. Once again, we had no choice but to set out on the road of evacuation. This time, our destination was Busan.

Up to that point, whenever we were stopped at checkpoints, we were first required to present identification documents. With that in mind, I went to a nearby security unit. I explained our circumstances to the unit leader, a man named Yoo Hong, and requested that they issue us each a “refugee certificate.” Not only did he kindly issue the certificates, but he even offered words of comfort, saying, “Be careful and have a safe journey.” I can never forget how I felt at that moment.

All the money we had brought from Pyongyang was gone, so we had no choice but to load suits and other items that might fetch some money, which were left behind at Mr. Gwak Nopil’s house, onto the back of the bicycle and leave Seoul. Even if we had left them behind, it was clear that nothing would remain if the People’s Army or the Chinese forces came flooding in. In fact, on January 4th, Seoul was once again taken over by the communist forces.

56

From Seoul to Busan

The second flight as refugees

On January 3rd, we set out once again, this time toward Busan, embarking on a 500-kilometer evacuation journey. This was our second evacuation. (During the January 4 retreat of the Korean War.) Riding on a bicycle and being pushed along, it was hardly a dignified sight, but it was undeniably a road of hope leading toward freedom.

After leaving Seoul, instead of following the Gyeongbu Line all the way to Busan, we decided to take the Jungang Line. The reason was that my paternal uncle, Jeong Gi-su, lived in a place called Jecheon, and we thought that if we stopped by there, we might receive various forms of help.

First, we passed through Seongnam and headed toward Icheon. This time, unlike the evacuation from Pyongyang to Seoul, unknown refugees did not line up together or move in large crowds. Rather, people traveled together with those from the same village or with their own families.

When night fell and it grew dark, we entered a village. In these villages, most houses were still inhabited, so empty homes were not easily found. Therefore, when we asked at a house for permission to stay one night, they would readily agree and allow us to borrow a room. When there was no spare room, we could rest in places like the kitchen or a shed.

Once a place to rest was secured, all that remained was to prepare a meal with the rice we carried, eat, and sleep.

Because this was our second evacuation, and we had experience from the first, we were able to maintain a bit more composure and travel at a more relaxed pace without rushing. It was best to enter a village early before nightfall and quickly arrange a place to sleep.

When the rice we had brought ran out, we stopped by a nearby small village.

▲ Refugees cross a river in winter

However, the people of this village seemed to have already evacuated, as most of the shops were closed. Nevertheless, we had no choice but to obtain rice somehow. So we went to a large house in the village, took out a suit we had brought from Mr. Gwak’s house, handed it to the elderly woman living there, and explained our situation. The dignified old woman, who appeared to be over seventy, perhaps felt pity for us, or perhaps coveted the suit. She opened the rice chest and gave us about one mal bag of rice. [A mal of rice is a traditional unit of measurement, roughly equivalent to 8 kilograms, about 17.6 pounds.]

Passing through Janghowon and Wonju, we searched for my uncle’s house in Jecheon in hopes of receiving help, but it had already been evacuated and was left empty, leaving us utterly discouraged. Still, we pressed on, and when we reached the ridge of Joryeong (Saenaejae), UN military police stopped us, saying, “Refugees must not travel on the main road.” That meant we had no choice but to take the difficult mountain path. By then, my leg had almost healed, so I resolved to force myself to walk even if it meant taking the mountain trail. But suddenly, the UN military police forcibly took away Teacher Moon and Won-pil.

I became extremely anxious, wondering if this would be our third separation. The first time was when we were taken by the security forces while fleeing from the North. The second time was when Teacher Moon and Won-pil were taken by the National Defense Corps in Seoul. And now, once again, I was left alone.

Even if I were left alone in such a place, I had no idea what to do. I was deeply worried, but after some time, the two of them returned. They said they had been put to work on a UN military vehicle.

From that point on, the road sloped downward, so I felt I could manage on my own.

“From here on, let’s throw away the cane and walk,” Teacher Moon said.

For nearly two months I had relied on a cane, sometimes riding the bicycle and sometimes getting off, so I was still not confident. But I steeled myself, threw away the cane, and found that I could walk even without it. From then on, I was able to walk by myself. The evacuation route continued through Danyang, Jeomchon, Punggi, Andong, and Uiseong.

58

Parting at Gyeongju

We arrived in Gyeongju in the evening. The city was overflowing with refugees, and it was very difficult to find any vacant rooms. After wandering around in all directions, we finally found a place in the city where we could rest, barely managing to secure lodging. It was a house whose front door had been boarded up in an X shape with planks. When we went to the house, a young man of about thirty came out. He asked why we had come, so we said, “We thought no one was living here because the door was boarded up with planks, and we hoped to stay for one night.”

He let us inside. Looking around the house, it seemed like a factory where something was being made out of planks. According to the owner’s explanation, they were making “small dining tables,” but because of the war all the workers had returned to their hometowns, so he had no choice but to shut down the workshop. We were able to rent a room.

When we came to say goodbye to the owner, telling him, “We are heading toward Busan today,” the young man replied that it would be all right for the younger two to go, but then, pointing at me, he said, “You seem to be the oldest and your body looks weak. Even if you go to Busan, it will be packed full of refugees, so wouldn’t it be better if the two of them went ahead first to get settled, and then you followed on afterward?”

Up to this point, I had crossed several life-and-death situations together with Teacher Moon and Won-pil, so I said, “No, I will also come to Busan.” But Teacher Moon said, “The kindness of this homeowner is admirable,” and then told me, “Chung-hwa, stay here for a while and wait. We will go to Busan and get settled, then contact you. At that time, we will join together again and undertake great work.”

Thus, I remained in Gyeongju at Jang Man-yeong’s house, while Teacher Moon and Won-pil continued on down to Busan. At that time, my feelings were extremely complicated. During the evacuation, I had experienced a number of very extreme situations with Teacher Moon, and had come this far for the sake of a great undertaking we were trying to carry out according to God’s will…

Left alone, my heart was filled with sorrow and a strong desire to go with them. However, I accepted this temporary separation, thinking that the evacuation journey would be easier with even one less person. Later, when Teacher Moon came to Gyeongju, I heard that at this time they walked as far as Ulsan, and from Ulsan were able to board a train for the first time. It was a train, but the situation was such that people were even riding on the roofs of the freight cars, and they barely managed to get on near a freight car, finally getting off at Choryang Station in Busan. That day, he said, was January 20, 1951.

60

Teacher Moon, driven by financial needs, comes looking for me

I remained alone in Gyeongju and became a boarder at Jang Man-yeong’s house. By April the weather had grown warm. Since I had been a boarder for a long time, I thought that I should at least do something to pay for my meals, so one day I discussed the matter with the owner.

He said, “During the war, even if we make things, they hardly sell, so the factory is closed.” But I suggested, “If you would just make low tables, I will load them onto a bicycle and go around selling them at the markets, so why don’t we try it?” The owner, too, became inclined to do so.

Thus, the three of us, the owner, his son who had worked at the factory before, and I, a refugee staying as a boarder, began making low tables.

At one time I would load twenty tables onto a bicycle and go to Pohang, to Yeongcheon, and also to Ulsan. I was not accustomed to trading, but somehow all the tables I carried out were sold, so I handed the proceeds over to the owner. Around Gyeongju there were markets in all directions. There were markets in Yeongcheon, Ulsan, Pohang, Eonyang, and Gampo, all about 20 or 30 kilometers from Gyeongju, and since markets opened every five days, I carried tables to those markets and sold them almost every day.

In the evenings, I also served as a private tutor for the owner’s son, who was attending middle school, and during my time as a boarder I more than adequately paid the cost of my meals.

While living this way, on March 7 of the following year, Teacher Moon, whom I had been waiting for so long, suddenly came from Busan. My joy was beyond words. However, since I myself was lodging at a factory with nothing but a single military blanket, there was no way for me to properly welcome Teacher Moon. The owner provided money so that I could at least host him for dinner, but there was no choice except to have him sleep at night in a room filled with wood scraps.

Teacher Moon spoke about what had happened in Busan during that time and about his plans going forward. It was all like a dreamlike story. It felt as though we had met again after several decades, and we talked together until deep into the night. The next day, Teacher Moon said, “Today I should return to Busan.”

As for my feelings, if only there had been one more room here, I would have wanted to establish an economic base and stay together with Teacher Moon, but since the circumstances were not yet favorable, it was not something that could be done.

As it happened, that day was a market day in Ulsan, so we decided to go together by train. In the morning, Teacher Moon watched me selling low tables at the market. After we ate lunch, Teacher Moon departed for Busan by train. I had been thinking that if many tables sold, I would at least give him some pocket money, but for some reason that day hardly any sold.

It was our first reunion in a year since parting in Gyeongju, and after seeing Teacher Moon off and returning, I fell into very deep thought. All I could think about was that I must somehow engage in business, raise capital, go to Busan, and devote myself together with Teacher Moon to achieving a great undertaking.

According to what Teacher Moon said, Won-pil was working at a restaurant, and Teacher Moon himself was staying as a boarder at the home of a former classmate with whom he had studied at a Japanese technical school [Aum Deok-mun 嚴德紋]. I thought that he must be very uncomfortable in such circumstances.

(In fact, at this time, he had come to see whether he might be able to live off me.)

I constantly thought about how I could establish an economic base even a single day sooner. Day after day, my entire work consisted of transporting low tables and selling them at the market. Should I simply hold on to this kind of work diligently and wait here with the hope that an opportunity would arise? Or would it be better to drop everything and go to Busan? I considered that as well, but even if I went to Busan, which was still overflowing with refugees, it seemed unlikely that there would be anything much to be gained, so I decided to remain in Gyeongju a while longer.

62

Reunion with Ok Se-hyun from Pyongyang

Seoul, which had been recaptured once again by the Communist forces on January 4th two years earlier, was retaken by UN forces on March 4th, exactly two months later. Around this time in Seoul, although the front lines advanced and retreated repeatedly, the overall situation gradually began to stabilize, and preparations for an armistice agreement were being promoted.

However, civilian casualties alone, north and south combined, were said to exceed two million, and the number of separated families surpassed ten million, so a shadow of anxiety and misfortune lay heavily over the people.

In the spring of 1953, that elderly woman Ok Se-hyun came to Gyeongju from Busan to find me, and after what had been a long time we met face to face. We had been separated when we fled from Pyongyang and had no way of knowing each other’s whereabouts, so meeting again like this was truly joyful. Ok Se-hyun told me her story of fleeing, news of Teacher Moon in Busan, how she was absorbed in raising the members, and how she had produced a manuscript to turn the Principle into a book. Remembering how Teacher Moon had always said during the time at Heungnam Prison that the Principle we discussed then must be organized and published, I was deeply moved that, even amid such an immense refugee life, she had managed to write it out at last.

I thought that we must establish an economic foundation as soon as possible, publish the Principle, distribute it nationwide, and carry out evangelism.

Thanks to the fact that Ok Se-hyun’s eldest son had brought a military truck, the entire family was able to come safely to the South. Once things were settled, we should work together in Busan, and we must strive as quickly as possible to establish an economic base.

We spoke fervently about how the time was soon approaching to carry out great works, together with Teacher Moon, for God’s will from six thousand years ago, and so on. Kim Won-pil seemed to be working at a U.S. military base at that time. A church had been established in Beomil-dong, and newly joined members were gathering to hear the Principle, and members who had been in Pyongyang were also said to have come to Busan. People living near the church also seemed to be coming to hear Teacher Moon’s message.

Ok Se-hyun stayed with me for one night and returned to Busan the next day. Then, after about a another month passed, a pastor named Lee Yo-han came to find me. He said that Teacher Moon in Busan had sent him. After guiding him to my room and listening to what he had to say, he told me, “Many new members have been gathering and listening to the Principle, so it would be good for Mr. Pak Chung-hwa to come quickly to Busan where the Teacher is.” Everyone’s hearts were swelling with the feeling that the time had just come to move forward together with all our strength in a great work for God.

The next day, Pastor Lee returned to Busan. I asked him to convey to Teacher Moon that I too would be coming to Busan soon, and then I started remembering earlier times. I recalled how, in Heungnam Prison, Teacher Moon had sat on top of a pile of empty sacks, closed his eyes, and told me that we must realize an ideal that would transform the mysterious world, namely the “Ideal Wonhwa Garden (圓和園理想).” The scene from that time vividly came back before my eyes. I wished that the world of hope would come even a single day sooner.

A world without sin, a world without jealousy, conspiracy, betrayal, or war—if one becomes a member of that ideal world, labor becomes a hobby, and one only needs to work about three hours a day. One can go to any country in the world, and when visiting a member’s home, sleeping, eating, and using things can all be done freely.

A world that takes joy in giving rather than receiving, a world that does not reproach others and finds joy not in being respected but in respecting others—if this ideal world spreads to every corner of the earth, then we will be able to share our hearts with any nation. Thinking that this world would be completed by “Teacher Moon Yong-myung,” who was at that moment suffering and laboring in Busan here and now, I could only feel gratitude.

I felt an urgent pressure in my heart that I must go to Busan as soon as possible.

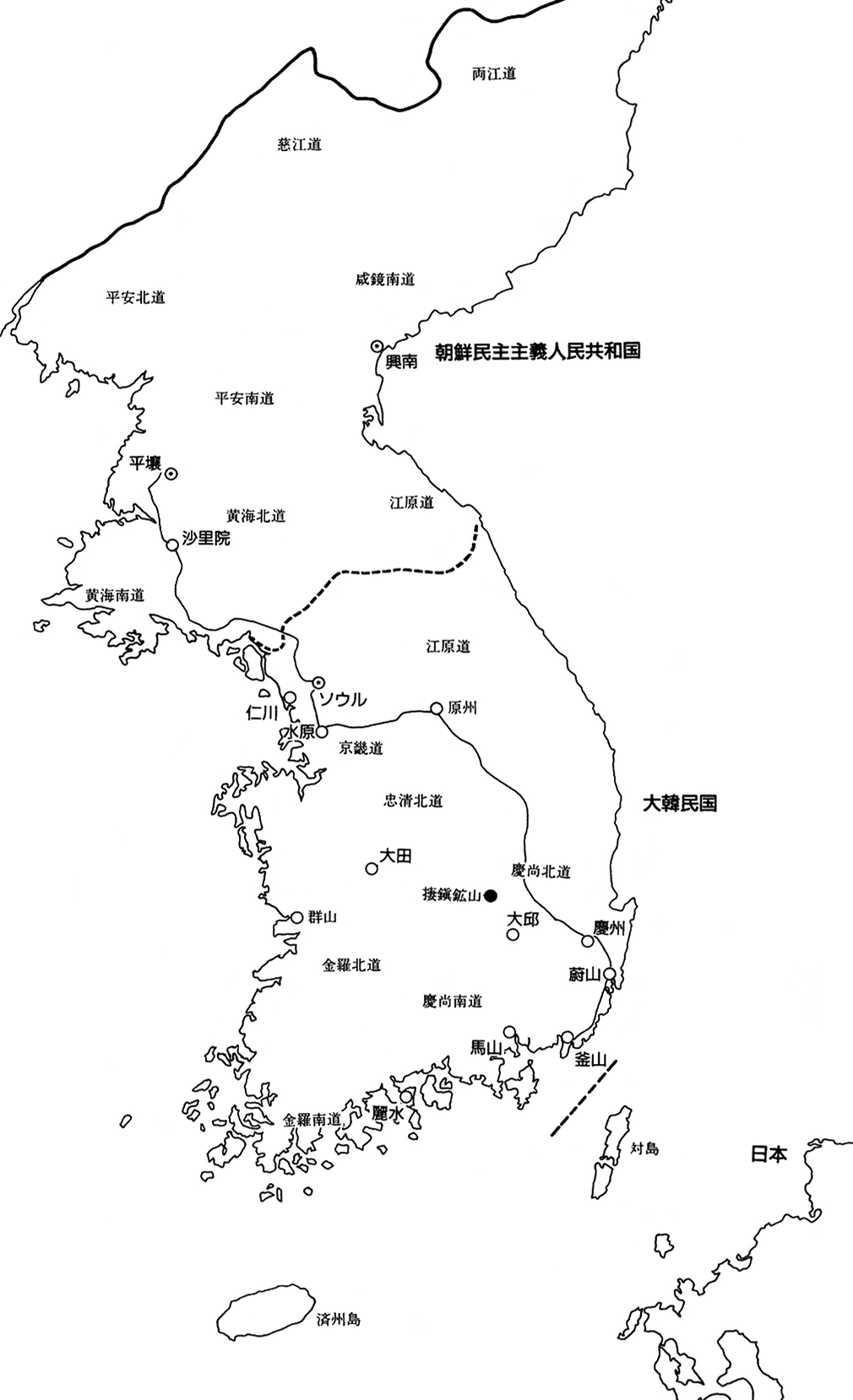

▲ Evacuation route from Pyongyang in the north to the south.

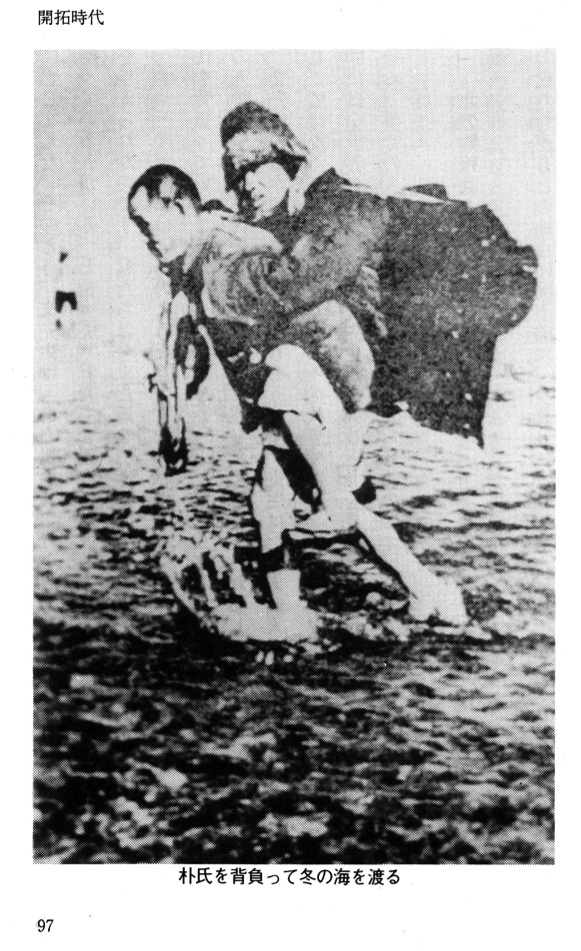

❖ Note: The route drawn by Pak on the above map does not include a detour to Yongmae Island off the west coast of North Korea. Kim Won-pil included such a detour on a map in his 1988 testimony book, The Way of the Pioneers, published in Japan. The reason for Kim’s invention of the story was the discovery of a photo of a refugee carrying another on his back through water. Pak was invited to the church headquarters in Seoul to confirm if he was in the photo. He immediately said it was not of himself or Moon. In a second edition of The Way of the Pioneers, Kim’s fictional account of a laborious journey through the sea to the island was removed, since Kim realized the Unification Church fraud had been disclosed. The photo was of a river crossing at a different location and at a different time to when Moon, Kim and Pak made their journey to the south of Korea. Below is the photo as used by Kim. Since Kim was with Moon and Pak on the journey, this proves Kim Won-pil to be a blatant liar.

▲ Page 97 of Kim Won-pil’s book: 朴氏を背負って冬の海を渡る “Mr. Pak being carried across the winter sea.”

[Sun Myung Moon and Mr Pak are not depicted. It was not the sea. It was a refugee carrying his father across the Han River at Chungju on January 14, 1951. The photo was taken by a US Army photographer who recorded the details.]

▲ Inserted is a photo of Moon taken in the 1950s.

Below is Kim’s fraudulent map, which he corrected in his later books. The detour to Yongmae Island 龍媒島 용매도 is clearly labelled.

▲ Page 43 of Kim Won-pil’s book showing a detour to Yongmae Island that Kim added to his narrative after the refugee photo was published in a Korean newspaper.

Pak Chung-hwa’s description of the journey in this book has proved to be the authentic one. See Chapter 6 for Pak’s comments on the photo.