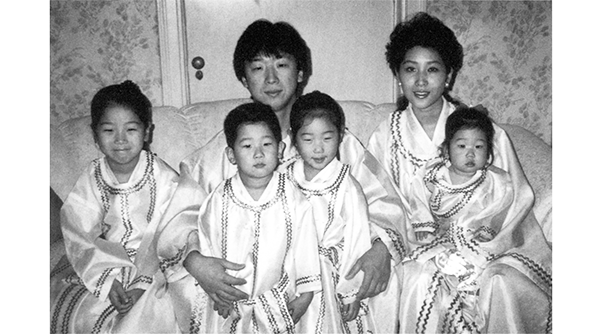

▲ Hyo Jin and I and our four children in November 1990, at our suite at the New Yorker Hotel in Manhattan. We are dressed in the religious robes of the Unification Church. Ordinary members wear white robes. The robes of the family of Sun Myung Moon are decorated with gold braid.

In The Shadow Of The Moons: My Life In The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Family.

by Nansook Hong 1998

Chapter 9

page 179

By 1994 my only ambition was to see my children grown so that I could leave my husband. I knew that Sun Myung Moon would never permit me to divorce Hyo Jin, but I fantasized that one day we could at least live apart. I dreamed of a time when I could live alone quietly in a small apartment, somewhere far from East Garden. The children would bring my grandchildren to visit me. I would be at peace.

It was a pathetic goal for a twenty-eight-year-old woman. I had just earned my undergraduate degree from Barnard College in art history, but I was writing off the next twenty-five years of my life. My passion for art, my vague thoughts of museum or gallery work, faded away, as dreamlike as the Impressionist paintings I favored.

In March I learned that I was pregnant again, and the joy I usually felt at the prospect of a new baby was this time mixed with dread. Each new birth would extend the length of my imprisonment.

It was a mystery to me how such precious lives could spring from such a poisonous union. It was my children who made me whole. With them I felt light and carefree. Their routines provided us with the only semblance of a normal life. I drove them to music and language lessons in a Dodge minivan just like other suburban moms; I helped them with their homework; I snuggled up with them at bedtime to read stories and to hear their daily concerns.

Too often, their worries were about their father. Nothing that went on in East Garden escaped the notice of our older son and daughters. Hyo Jin’s drunken rages, his cocaine stupors, his volatile temper, were impossible for them to overlook. They were awakened in the middle of the night by the sound of us fighting. They questioned why their father slept all day. “Why do we have a bad dad?” the older ones would ask. “Why did you marry him?”

I was grateful that Hyo Jin stayed away as much as he did, working at Manhattan Center Studios and sleeping at our suite in the old New Yorker Hotel. It reduced the tension in the mansion, which we now shared with In Jin and her family. The children and I managed some happy, even silly, hours together. One spring I had taught myself to ride a bicycle in the mansion driveway, to the great amusement of my more competent children.

Manhattan Center, which was originally built in 1906 as the Manhattan Opera House by Oscar Hammerstein, had become the focus of Hyo Jin’s life. The Unification Church had purchased the property, along with the New Yorker Hotel next door, in the 1970s. Manhattan Center was little more than a practice hall when Hyo Jin had taken charge of the production studios and the business operation in 1985. I was surprised that Sun Myung Moon had entrusted such a major enterprise to a son who had neither the education nor the experience — to say nothing of the discipline — to act as a chief executive officer. I should not have been. All over the world, when the Unification Church acquires new businesses, those enterprises serve as employment opportunities for the family of Sun Myung Moon.

For the first time in our marriage, for the first time in his life, Hyo Jin Moon at age twenty-six had a job. He supervised the production of videos for the church and he continued to record with his band of church members. I was no fan of rock music, but it was certainly true that Hyo Jin was a talented guitarist with a beautiful voice. He loved his music; it was the one unspoiled pleasure he had in life.

His employees at Manhattan Center were all members of the Unification Church, even though Manhattan Center Studios claims to be an independent corporation with no overt connection to the church. His employees accorded Hyo Jin the respect and loyalty due the son of the Messiah. With him they turned Manhattan Center into a sophisticated multimedia studio, with professionally run audio, video, and graphics departments. Hyo Jin’s elevated spiritual standing made for strained work relations, however. Imagine answering to a boss you could not question, who interpreted any hesitation to carry out his orders as a sign of betrayal. It was a recipe for disaster.

Money flowed in and out of Manhattan Center in what could generously be described as a liberal and informal fashion. Some weeks employees did not get paid because Hyo Jin had earmarked the thousands of dollars sitting in the safe for the purchase of new equipment. Most lived rent-free in the New Yorker Hotel next door. When Manhattan Center’s conventional sources of revenue — studio bookings and ballroom events — fell short, Hyo Jin would tap a church organization, such as CARP, to pay for a new video camera or the electricity bill. Personal “donations” to Hyo Jin financed the building of new studios and recording facilities. Church funds, channeled to Manhattan Center from True Mother, were recorded on the books as “TM.”

Manhattan Center became the fuel that powered Hyo Jin’s moral collapse. It was a source of ready cash to finance his cocaine habit, his growing arsenal of guns, and his nightly drinking binges. Manhattan Center provided Hyo Jin, who hated to drink alone, with a stable supply of drinking companions, all of whom had no choice but to attend to this True Child.

Most members of the Unification Church get no closer to the True Family than the distance between the stage and their seats at some rally. For the staff of Manhattan Center, the opportunity to work directly with Hyo Jin Moon was a matter of great pride. It soon became a source of spiritual conflict for many of them, however. He would order his inner circle to accompany him to Korean bars in Queens, where he cavorted openly with “hostesses” and drank himself senseless. He pressured people to take cocaine, people who had been drawn to the Unification Church because of its prohibitions against the very acts of self-destruction in which Hyo Jin was engaged.

As his cocaine abuse escalated, so did his belligerent behavior toward his staff and his family. His verbal abuse of me had grown from obscenity-laden insults to threats of physical harm. He would open the gun case he kept in our bedroom and stroke one of his high-powered rifles. “Do you know what I could do to you with this?” he would ask. He kept a machine gun, a gift from True Parents, under our bed. At Manhattan Center, those who displeased him became accustomed to hearing graphic descriptions of the violence that would come to them if they betrayed Hyo Jin Moon. An accomplished hunter, he once detailed for a gathering of his inner circle exactly how he would like to skin and gut a member of his staff who had recently left Manhattan Center.

It is difficult for anyone outside the Unification Church to understand the bind those close to Hyo Jin at Manhattan Center found themselves in. On the one hand, their leader was engaging in activities that were inimical to their beliefs. On the other hand, he was the son of the Messiah. Perhaps he had some special dispensation to act as he did. If they did not obey and join him in proscribed behavior, were they substituting their own inferior judgment for that of a True Child? Should they be honest with the Messiah or loyal to the son of the Messiah? Would they be protecting Hyo Jin Moon by exposing him or by shielding him?

Even if one or more of them had had the independence of mind to question Hyo Jin’s actions, unlikely given the authoritarian nature of the church, who would they have told? One doesn’t just call up East Garden and ask to speak to Sun Myung Moon. Even if a member tried to make an appointment to see Mrs. Moon, that information would soon be public knowledge. Hyo Jin would not have been pleased to discover that one of his trusted advisers had gone to True Parents to inform them that their son was an alcohol-abusing, drug-addicted womanizer.

On the contrary, the inner circle had enough experience with Hyo Jin’s unpredictable temper to go to any lengths to appease him. He terrorized his workers, reminding them whenever they displeased him that he was “a mean son of a bitch,” one of his favorite self-descriptions.

No one was learning that better than I. In September Hyo Jin beat me severely after I found him taking cocaine with a family member in our bedroom at 3:00 a.m. I could not contain my anger. “Is this how you want our family to live?” I asked him. “Is this the father you want to be to our children?” I told him I could not live like this anymore. I tried to flush the cocaine down the toilet, spilling some on the bathroom floor in the process. He pushed me to the floor and made me sweep up what white powder I could retrieve. He smashed his fist into my face, bloodying my nose. He wiped my blood on his hand and then licked it off. “Tastes good.” He laughed. “This is fun.”

I was seven months pregnant at the time. While he punched me, I used my hands to shield my tummy. “I’ll kill this baby,” Hyo Jin screamed and I could see he meant it.

The next morning my tearful children gave me ice for my blackened eye and hugs for my battered spirit. I can’t say Hyo Jin hadn’t warned me. How often had he told me that there was a deep well of violence inside him? “If you push me too far, I won’t be able to stop myself,” he would say. I knew now that he was not exaggerating.

Hyo Jin felt no regret for the beating he had administered. He told his inner circle at Manhattan Center later that he smacked me because I had been “bugging” him and that I reminded him of a teacher he had once had at school, who always tried to humiliate him in front of the class. I was a pious scold, he said, a self-righteous bitch.

As strong as his contempt was for me, it did not approximate his hatred of his Father. He loathed and loved Sun Myung Moon in equal measure. He mocked him in front of me and in front of his associates at Manhattan Center as a senile old fool who should know his time to leave; he denounced him as an uncaring father who had never had time for his children. He blamed his father for the taunts of “Moonie” hurled at him by his American classmates when he was a boy. He resented the burden of being the heir apparent to the Unification Church, but he chafed even more at his own inability to live up to his father’s expectations. He kept a gun at Manhattan Center, whose security chief often purchased weapons for him. When he was high, Hyo Jin would wave the gun around wildly and threaten to shoot his father if Sun Myung Moon ever tried to interfere with his control of Manhattan Center.

That control was absolute. He used Manhattan Center money as if it were his own and had his own paycheck deposited into a joint account with Rob Schwartz, his financial adviser at the company. Manhattan Center was there to serve his every whim. In 1989 and again in 1992, he had instructed Schwartz to buy a new Mercedes for Father with company funds. On another occasion he purchased an eighteen-foot fishing boat and trailer for the use of the extended Moon family. What those cars and that boat, all of which were kept at the compound in Irvington, had to do with the business of Manhattan Center was anyone’s guess.

The casualness with which Hyo Jin mingled his personal funds and church money and business accounts would have intrigued the Internal Revenue Service. In 1994 he ordered Rob Schwartz to give one of his younger sisters thirty-thousand dollars. There was internal debate at Manhattan Center about how best to disguise this transfer of funds. In the end, proceeds from the Mr. and Miss University Pageant held at Manhattan Center were kept off the books and thirty-thousand dollars was handed to Hyo Jin to give to his sister. The year before, a group of Japanese members of the Unification Church was touring the United States. On a visit to Manhattan Center, they made a personal “donation” to Hyo Jin of four hundred thousand dollars in cash. He kept some of the money and used the rest for pet projects at Manhattan Center. He never reported the gift on his tax return or paid a dime of taxes on the money.

In February 1994 Hyo Jin carried a Bloomingdale’s shopping bag into Manhattan Center containing six hundred thousand dollars in cash. I had helped him count out the money earlier in the day in our bedroom. He gathered his inner circle of advisers in his office, and while their jaws dropped open, Hyo Jin asked if they had ever seen so much money. What he didn’t tell them was that he had skimmed off four hundred thousand dollars for himself of the one million dollars Father had given him to finance Manhattan Center projects. Hyo Jin stashed the money in a shoebox in our bedroom closet. By November he had spent it all, mostly on drugs.

It is probable that Sun Myung Moon did not know until November of 1994 the extent to which Hyo Jin had turned Manhattan Center into his personal petty cash drawer and the family suite on the thirtieth floor of the New Yorker into his private drug den. He did not know because he did not want to know. The Reverend and Mrs. Moon had set the tone for their parental relationship with Hyo Jin back when he was a boy, expelled from school for shooting at classmates with a BB gun. On that occasion, and in every troubling incident since, they had not forced their son to accept responsibility for his actions. He grew up believing that there were no consequences for his misdeeds, and his parents, and the church hierarchy, did nothing to disabuse him of that notion.

That fall, for instance, Hyo Jin had been a guest speaker in a course called Life of Faith at the Unification Theological Seminary in Barrytown, New York, where he was enrolled as a part-time student. Another student asked Hyo Jin a general question about his remarks and Hyo Jin took offense. Without a word he walked over to where the student was seated and began punching him. The student remained seated and did not strike back.

Hyo Jin received two letters from Jennifer Tanabe, the academic dean, after the incident. One was a joint letter of reprimand to Hyo Jin and the student he assaulted, Jim Kovic; the other was a personal note to Hyo Jin advising him to disregard the official letter. “Please understand that my intention in addressing this letter to you, as well, is not to accuse you but to protect you against any possible accusation. I will do my very best to support you. This is my determination before God,” she wrote, incredibly ending her note with an apology to a man who had beaten up a student in one of her classrooms. “I am sorry to bring such bad memories of your experience at UTS. I hope that in the future you will find UTS to be somewhere that can bring you joy and inspiration.”

By November Hyo Jin was about to run out of excuses and defenders. The month began with the birth of our second son and fifth child, Shin Hoon. Hyo Jin was out at the bars when I went into labor, so I drove myself to the hospital with the baby-sitter in the passenger seat. I wanted her to learn the way so that she could bring the other children to visit me and their new brother. Before we left I put the children to bed. I told them I was going to the hospital to have the baby and that they should go to school the next day without telling anyone where I was. My desire for privacy in the suffocating world of the Moon family had become paramount. I called my brother Jin in Massachusetts to let him know I was on my way to Phelps Hospital and to ask him to call our parents in Korea.

I didn’t care that Hyo Jin was not with me. This was my baby, mine and my children’s. He had nothing to do with us as a family. If he preferred the company of barmaids, why should he be there for the birth of my son? At 4:00 a.m., when I was told I needed a cesarean section, my doctor insisted I call my husband. He was asleep. He assumed I was in one of the children’s rooms down the hall. He urged me to come and service him sexually. He was startled to hear that I was about to be wheeled into the operating room.

He was too tired to come, he said. “What hospital is it anyway?” he asked. This was our fifth child and he did not know where they were all born? I was enraged. I did not answer. Hyo Jin began yelling. I hung up, but after I calmed down, I called back. “Forget it,” he said coldly. “I’m not coming. You can bring the baby to me.”

I saw my first glimpse of “Hoonie” through my tears. A nurse kept wiping my eyes as the doctor lifted this big boy, almost nine pounds, from my womb. He had a full head of black hair. The umbilical cord had been wrapped around his arm, complicating a natural delivery. His eyes were half closed but he had a healthy wail.

Hyo Jin did not come to see him for two days. His pride and his indifference kept him away. I was as stubborn as Hyo Jin, but I called to ask him to see his son. He stayed for only a few minutes with me and viewed Shin Hoon through the nursery window. He never asked to hold him. That night the babysitter brought my children. I was so happy to see them. They all posed for pictures with their new baby brother and begged me to come home soon.

I came home the next day, though the doctors wanted to keep me longer because of the surgery. I did not want anyone in the Moon compound to know I had had a cesarean section. It was such an anomaly to be in possession of information the Moons did not have; I wanted my surgery to be my secret. Hyo Jin came with the children and the baby-sitter in two cars to pick us up at the hospital. When it took longer than he had patience for to adjust the infant seat, he took off with Shin Gil for home, leaving me to ride with the baby-sitter. That night Hyo Jin announced he was going to New York. What I did not learn until later was that my husband had chosen the very day I brought our baby home from the hospital to take a lover. He slept with Annie, an employee at Manhattan Center, in our bed in our suite in the old New Yorker Hotel.

I knew Annie from the dozens of letters she had written to Hyo Jin since she first saw him at a church martial arts demonstration in Colorado several years before. Her letters read more like fan mail than anything else. Hyo Jin often got similar letters from young people in the church, men and women, who looked up to him as the son of the Messiah. I never took Annie’s infatuation with Hyo Jin seriously. An American herself, she was married to a Korean member and they had a young son. Annie had come to New York that year to work for Hyo Jin at Manhattan Center after appealing to him to bring her and her husband back from Japan, where they were stationed for the church.

Hyo Jin talked about her often, but I did not suspect the nature of their relationship initially. Maybe I did not want to see what was becoming more and more obvious to everyone else around them. I worried more about his dependence on cocaine. He was closeted in his room all the time that he was not at Manhattan Center. As it turned out, I was not alone in my concern.

Twenty-one days after the birth of a child, we hold a prayer service in the Unification Church to give thanks to God for the health of our baby. I held an informal service with my children. Hyo Jin had been out drinking all night and had not returned. His sister Un Jin came by that afternoon to see the baby. We had not been close for years, but I would never forget the kindnesses she showed me when I first came to East Garden.

She confided that she was worried about Hyo Jin. He had lost a lot of weight. He wasn’t eating. Did I think his problems with booze and drugs had gotten worse? Did I think True Parents should send him to rehab? I told her what I saw of his deteriorating lifestyle, but I expressed skepticism that he would voluntarily confront his addictions.

The very next day, Hyo Jin threw a Thanksgiving party at Manhattan Center for the staff. He served wine. Only his inner circle really knew about Hyo Jin’s drinking and cocaine use. The rest of the staff were shocked to see alcohol at a church function. When the Reverend Moon found out, he ordered the staff at Manhattan Center to meet with him, without Hyo Jin. He reminded them that Sun Myung Moon was the leader of the Unification Church; they were to support Hyo Jin by keeping him away from dangerous situations.

I called Hyo Jin’s assistant, Madelene Pretorius, to find out how the meeting went. We did not know one another well. We had met only once, when she came to videotape the children at a school play. She told me what Father had said and admitted that they had not told the Reverend Moon or me the whole truth. He had asked them if they smoked or drank with Hyo Jin and no one had admitted it. The truth was, she said, that they smoked and drank with him all the time in bars and in our suite at the old New Yorker Hotel.

I was horrified. What he did to himself was bad enough, but to drag other church members into the sewer with him was unforgivable. That he used our apartment to engage in this behavior enraged me. This was the beginning of the end of my marriage, though I didn’t know it then. Something in me was about to snap. I had accepted that it was my fate, my divine mission, to live a life of misery with this evil man. But I could not accept that the members of a church I still believed in were condemned to be led into sin by Hyo Jin’s abuse of power.

I called him at Manhattan Center. I was much braver on the telephone than I would have been in person, where he might have beaten me. I told him on the telephone that I thought he was an animal, that the children and I did not want him to come home.

It was a shortsighted reaction on my part, because, of course, he did come home, and when he got there he came looking for me. In my fury, I had already cleaned out his closets, packed his bags, cut his pornographic videos into shreds, and stacked it all in the storage room down the hall. I heard the front door slam. He ran up the stairs, grabbed me by my shirt collar, and dragged me into his room. He pushed me roughly into a chair, shoving me back down whenever I attempted to stand. “How dare you try to embarrass me in front of people at M.C.?” he screamed. “Who are you to tell me what to do?” He stood over me, slapping me and pushing me the whole time. I had no avenue of escape.

I was saved only because he was late for a meeting with his probation officer. He was still on probation for drunken driving. He tried to call and cancel the appointment, pleading a family emergency, but his probation officer insisted he come. He had missed too many appointments. “When I get back, I want a family meeting,” he told me. “You are going to tell the children that you were wrong to criticize Dad, that Dad is free to smoke and drink beer, that you are a bad mother. Do you understand?” I said that I did. I would have said anything to get him to leave.

No sooner had he gone than I got a telephone call from Mrs. Moon’s maid. “Father wants to see you right away,” she said. I thought I was about to be lectured again for failing to help my husband find a righteous path. I had had enough; it was time for me to take the initiative. The rising level of abuse had emboldened me somehow. I had not consciously decided that I was not going to take his beatings anymore, but that night, in the Moons’ study, I stood up for myself for the first time.

“Father wants to speak with you,” Mrs. Moon said as I entered their suite. “Could I please talk with you both?” I asked. “There is something I need to tell you.”

The Reverend and Mrs. Moon listened in silence as I described the scene that had just transpired. “It is not just me and the people at M.C. who are being affected,” I said. “Hyo Jin wants me to tell the children that his use of alcohol and drugs is O.K.” That was enough to spark a reaction in Father. “No. No,” he said, “you have to teach the children right from wrong.” I kept looking at my watch. I told True Parents I needed to get back before Hyo Jin did from his meeting with his probation officer.

The Reverend Moon was quiet for a few minutes: “I am going to send you to M.C. to keep an eye on him. You are to be his shadow. I will put you in charge. You can make sure he does not use money for drugs and drinking.”

I was surprised, but I knew that his use of me as his eyes and ears at Manhattan Center had less to do with his faith in my ability than with his certainty of my loyalty. The staff at Manhattan Center owed an allegiance to Hyo Jin; I followed True Father. He was right in the short run. In the long run, as we were all to discover, I realized that my ultimate loyalty was to God, my children, and myself.

When I returned to the mansion, Hyo Jin had not yet returned. I called our oldest child to my room. “Dad wants a family meeting,” I told her. “I’m going to have to say some things I don’t believe, because otherwise your dad will get very angry.” She was appalled that I would even consider saying what he demanded. “You are not a bad mom. You are a good mom. You can’t say what he does is O.K. when you know that it isn’t.” I could see that she was disappointed in my willingness to compromise the truth. I was ashamed in front of my twelve-year-old daughter, whose sense of justice was finely honed at a young age.

I was selfish. I wanted to avoid more violence, more screaming. When he returned and asked me to tell the children I had been unfair to Dad, I did it. My daughter’s eyes filled with tears, but she was not sad. She was angry. “That’s a lie,” she yelled at her father. “Mom is good. She is with us all the time. You are never here. What do you know?” Hyo Jin turned his fury on her, denouncing American schools for breeding disrespectful children.

I felt like a coward witnessing my little girl’s courage. When Hyo Jin calmed down, he told her he had to spend time away from the family to pursue his mission for the church. I could not help but think of the irony: this was the excuse he had so despised when it came from his own father.

I was surprised that, despite his angry protests, Hyo Jin accepted my new role at Manhattan Center. He did not suspect why Father had placed me there, and since he had so little respect for me, he probably thought my presence would be no threat to him. He soon learned otherwise. As one of my first directives, I set up a meeting between Hyo Jin’s inner circle and Sun Myung Moon at East Garden. The Reverend Moon told them as explicitly as he could that they were not to take drugs with Hyo Jin or to drink with him. They were to give their allegiance to Father, and at Manhattan Center they were to follow my directions, not Hyo Jin’s.

As angry as I was at Hyo Jin, I was still susceptible to his accusation that it was my lack of understanding and support as a wife that led him to drink and abuse drugs.

If I was responsible in some way, I had to try one more time, with all my heart, to make things right, if not for us then for God. I spent all of my free time in December in Hyo Jin’s company. I went with him everywhere. I sat with him at home while he snorted cocaine.

The drug loosened his tongue and I listened for hours to his stream-of-consciousness pronouncements about God and Satan and Sun Myung Moon. The more I heard, the more convinced I became that Hyo Jin had no real sense of right and wrong. It was sad to hear him devise pathetic excuses, to tailor his morality to suit his circumstances.

His drug-induced monologues invariably portrayed him as the victim of his parents’ neglect, of his wife’s harsh judgment, of the church’s unrealistic expectations. I listened for any hint that my husband was capable of taking some responsibility for the bad choices he had made and was continuing to make.

I heard nothing of the kind. All of Hyo Jin Moon’s problems were the fault of others. As long as that was his attitude, how could he ever really serve God? How could he ever really be a good father to our children?

At Manhattan Center I set about trying to get the company’s financial and spiritual house in order. I instructed Hyo Jin’s assistant, Madelene Pretorius, that there were to be no more “petty cash” payments of hundreds of dollars at a time to Hyo Jin. Staff members who were paid huge salaries for little work were to be reassigned. All major decisions would have to be approved by me.

I had another mission at Manhattan Center as well. I was determined to find out whether Hyo Jin and Annie were lovers. Madelene suspected they were. Even my brother-in-law Jin Sung Pak had hinted there was something going on between them. I asked Hyo Jin directly many times, prompting the denials I expected but did not believe. After I began working at Manhattan Center, he taunted me about their ambiguous relationship. “Why do you worry about Annie?” he would ask, as if he were baiting me.

At the end of December, I decided I would hammer away at this topic until he confessed. It took hours of gentle coaxing for the truth to emerge. “No, I did not touch her,” he insisted at first. “Well, maybe I kissed her,” he conceded. “Maybe we had oral sex.” His rationalizations got more strained the more impropriety he was willing to admit. “I did penetrate her, but I didn’t ejaculate so it doesn’t count,” he said, before finally confessing: “I did ejaculate, but it doesn’t matter because she is on the pill,” I wondered if this guy even knew how pathetic he sounded.

I was very calm as he described his betrayal of our family. I had known in my heart all along; his confession was just confirmation. He began to cry and beg my forgiveness. I told him I would try to forgive but that I would not sleep with him until he had paid for his sin. “Why Annie?” I asked impulsively. “She’s not even that pretty.” It was as if I had held a match to gasoline. He exploded in rage: “She’s beautiful!” he yelled. “She’s not the only one. All the women in the church want me. I’ll fuck the prettiest girl I can find. I’ll show you.”

I was numb. This was the man who claimed to be the son of the Messiah, a man who had stood up at a church service a few years before and preached about the sacredness of the Blessing. “How can you connect to the Messiah if you are indulging and wallowing in the sensuality of the fallen world? You can’t. That’s why the idea of sacrifice has been promoted and endorsed,” he had told a Sunday-morning gathering at Belvedere.

“If Father told you to go out of this room and go to bars, get loaded and go to the streets where prostitutes walk and dwell among them, are you strong enough, do you love Father enough to overcome the kind of temptation that you might or might not expect there? Could you keep your purity and integrity? Could you truly do that? Living in that environment for the sake of changing the people is a good reason for living there. But do you know Father enough to overcome the temptation of touching a woman, of looking at beautiful women, or being intoxicated where your ability to make a sensible decision becomes weaker and weaker? Under that circumstance can you hold on to Father? Are you strong enough not to abandon Father regardless of the circumstances?”

I knew now that Hyo Jin Moon was addressing those questions not to the members but to himself and the answer, sadly, was no. Continuing the pattern that had defined his life, Hyo Jin refused to take responsibility for his adultery, the single worst sin in the Unification Church. He told me, as I later learned he had told Annie and his inner circle, that the church’s sexual prohibitions did not apply to him. Father had been unfaithful; as the son of the Messiah, he could be, too. His sexual liaisons were “providential,” or ordained by God.

“I trusted Hyo Jin who said ‘I know what I’m allowed to do.’ He never even gave me a hint that I would be falling with him,” Annie would write me later. “Madelene told me some story about Father having a relationship outside of Mother and a son being born. This was later confirmed to me by Hyo Jin and Jin Sung Nim. We discussed if it could be true and what it meant. I never questioned Father’s purity or his course. But I certainly began to feel that there must be a lot going on providentially within the True Family that I can’t understand or judge.”

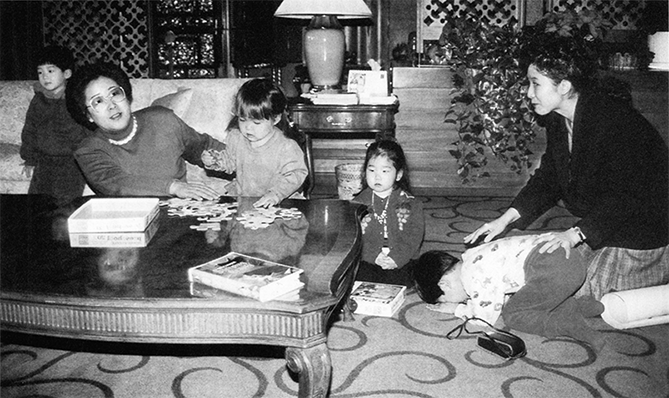

▲ In the family room at East Garden, I instruct my son Shin Gil how to bow before his grandmother, Hak Ja Han Moon. She is surrounded by grandchildren.

I went directly to Mrs. Moon with Hyo Jin’s claims. She was both furious and tearful. She had hoped that such pain would end with her, that it would not be passed on to the next generation, she told me. No one knows the pain of a straying husband like True Mother, she assured me. I was stunned. We had all heard rumors for years about Sun Myung Moon’s affairs and the children he sired out of wedlock, but here was True Mother confirming the truth of those stories.

I told her that Hyo Jin said his sleeping around was “providential,” and inspired by God, just as Father’s affairs were. “No. Father is the Messiah, not Hyo Jin. What Father did was in God’s plan.” His infidelity was part of her course to suffer to become the True Mother. “There is no excuse for Hyo Jin to do this,” she said.

Mrs. Moon told Father what Hyo Jin was claiming and the Reverend Moon summoned me to his room. What happened in his past was “providential,” Father reiterated. It has nothing to do with Hyo Jin. I was embarrassed to be hearing this admission from him directly. I was also confused. If Hak Ja Han Moon was the True Mother, if he had found the perfect partner on earth, how could be justify his infidelity theologically?

I did not ask, of course, but I left that room with a new understanding of the relationship between the Reverend and Mrs. Moon. It was no wonder she wielded so much influence; he was indebted to her for not exposing him all these years. She had made her peace with his faithlessness and betrayal. Perhaps all the money, the world travel, the public adulation, were compensation enough for her.

They would not be enough for me. For once Hyo Jin Moon was going to see that every action brings a reaction, that for every misdeed there is a consequence to be faced. I received the Reverend and Mrs. Moon’s permission to send Annie away. But first I gave her the chance to tell the truth. I wanted her to admit what she had done to me, to her husband, and to God. She vowed in the name of True Parents that she and Hyo Jin had done nothing wrong.

After I had banished her from Manhattan Center, she wrote to me from her parents’ home in Maine. Her husband had taken their son and returned to Japan. He wanted a divorce. “Now, I can taste your pain, your anguish and your tears…,” she wrote, suddenly contrite and begging my forgiveness. She wrote several more times, describing her sex life with my husband in more detail than I needed to read, claiming to accept responsibility for what she had done.

There is no Feast of the Epiphany on the Unification Church calendar, but I had my own epiphany one day in January of 1995. The seeds of my emancipation had been sown that fall when Hyo Jin had his blatant affair and flaunted his drug use in front of church members. On a cold mid-January day I had one of those moments of revelation that I had only read about. Hyo Jin was dressing to go out to the bars for the evening. The events of the last few months had done nothing to alter his habits. I watched from a chair in the master bedroom as he stared at his reflection in the full-length mirror. He had always been very vain. But as he tucked in his shirt and fussed with his hair, I felt a detachment I had never experienced in my marriage. Even my revulsion was gone.

There was no voice from on high, there was no blinding light from above. I just knew: God no longer expected me to stay. My husband would never change. God himself had given up on Hyo Jin Moon. I was free to go. I was overwhelmed with a spirit of well-being. For Hyo Jin I felt only pity. He was a lost soul who had no conception of right and wrong and no real understanding of God.

It is a long road from resolution to action for a battered woman and one that few of us are able to walk alone. I was lucky I did not have to. Madelene Pretorius hardly knew me. She had worked for Hyo Jin for three years. She was an unlikely ally. That winter she spent her days listening to Hyo Jin complain about me in the office and her nights listening to me complain about him on the telephone. She was torn between her loyalty to the divine son of the Messiah and her recognition of the very human, abusive man we both knew. Hadn’t Hyo Jin once thrown an ashtray at her head in a barroom? Hadn’t he doused her with water when a bottle he threw at her crashed on the wall above her chair?

She was the first person outside my family I had ever been able to talk to about my feelings. Even with my family, I hid more than I revealed about my life. I did not want to hurt them by letting them know the extent of the abuse my children and I were enduring. Madelene listened with a patience and concern I had never known. I had never had a real friend. I don’t pretend that in those early months I was a friend to her. But she was to me. It would be a long time before I stopped acting like an officious member of the True Family and she stopped acting like a subservient member of the Unification Church. But even at the beginning, I saw a glimpse of what an honest relationship between equals could really be like.

At the time, Madelene was going through a personal crisis of her own. She had been matched and married through the church to an Australian man. She cared for him but did not want to follow him when he decided to return to his homeland. She struggled with her decision. Divorce is a creation of man; the Blessing is eternal. Unificationists believe that you remain mated even after death, in Heaven. It was revealing that Hyo Jin encouraged her to divorce; his self-interest in keeping her working at Manhattan Center was stronger than his commitment to a central tenet of his faith.

I wish I could say I helped her through her ordeal, but I was too wrapped up in my own problems, too inexperienced at friendship to really understand its reciprocal nature. It is a measure of the kindness Madelene showed to me that she was willing to help me without any expectation that I could help her in return. Madelene went home to South Africa for a month to make some decisions about her own life. When she returned in late February, she told me that she was getting a divorce and I told her I was leaving Hyo Jin.

Once I had made up my mind to go, I knew it was just a matter of time, but I was surprised to hear myself say the words out loud. Madelene and I talked in the laundry room in the basement of the mansion at East Garden so that Hyo Jin would not see us. He was so possessive and controlling that he erupted whenever he thought I was forming an attachment to anyone outside the True Family.

I began to cry as we talked. I said I hoped we could stay in touch after I left, though I knew that might be difficult for her. Madelene was saddened, but not surprised, by my news. She said that a part of her wanted to tell Hyo Jin, to try to shake him into seeing what he was about to lose. She would not do that, she said, because it would only have provoked him to beat me again or to issue one more false promise to change. We both knew my marriage was beyond saving. I had been seduced so many times into believing that God would touch Hyo Jin’s heart or that Sun Myung Moon would exercise some moral leadership in his own household. It was not to be. I was at the end of the line.

That spring, Hyo Jin’s behavior only worsened. Father had prohibited him from returning to Manhattan Center for two years, until he got his addiction problems under control. Hyo Jin called Manhattan Center and threatened to come down and smash the studio equipment. He was still being paid, of course. The Moons called it a disability payment, even though the company carried no disability insurance on its employees. Hyo Jin, in the meantime, was doing nothing to address his substance abuse. He would not enroll in a drug rehabilitation program; he would not see a therapist. If anything, he was spending more time closeted in his room, using cocaine and drinking. He would send Shin Gil to the refrigerator for beer and then lock himself in his room. For the sake of my children, I knew I could not remain in this environment much longer.

The final straw came when True Parents told me they thought that Hyo Jin was ready to return to Manhattan Center. He was bored at East Garden and needed productive work. Hyo Jin’s first project when he returned to Manhattan Center, he told me, would be to make an international singing sensation out of a bar girl who entertained at a Korean club in Queens. I knew the Moons were making a terrible mistake, that Hyo Jin was in worse shape than ever and a return to Manhattan Center would just broaden his opportunities to drink and use cocaine. I had my own suspicions about his real intentions toward the Korean bar girl. I knew the Moons would not listen to me. In April they did listen to concerned church members who wrote to protest Hyo Jin’s reinstatement in his old job.

Dearest True Parents,

On behalf of all the members of Manhattan Center, we the leaders and department heads come before you with a humble heart of repentance for our inability to create an environment that could support and protect Hyo Jin Nim and assist him in fulfilling his historical responsibility.

We wish to express our loyalty and support to our True Parents at this very crucial time, and wish to convey the following key points:

1. Our primary desire is to ensure that Manhattan Center is a place that can be completely claimed and used by God, True Parents and the worldwide Unification movement.

2. That as such, we absolutely pledge to uphold True Parents’ tradition and to maintain and substantiate that standard as the force that guides the lives of all members in the mission at Manhattan Center. We also realize that only through connecting M.C. to True Parents’ greater vision do our efforts have any value at all.

3. That on this foundation we wish to express our heart of love for Hyo Jin Nim, and the desire to support and help him in fulfilling his position and responsibility.

4. Therefore, based on this heart, we absolutely do not want M.C. to be a place that Hyo Jin Nim can use to make his problems worse. We want to be totally sure that he is protected from using M.C. in any way that may bring greater harm to himself and to the spiritual lives of members, to the growing business foundation, or to the reputation and foundation of the Church.

5. We therefore wish to support our True Parents in any decision they make with regard to Hyo Jin Nim. But we, as leaders of Manhattan Center, humbly request that Hyo Jin Nim not be restored to his position of responsibility here until he has completely overcome his drug and alcohol problems, and can truly uphold God’s standard at Manhattan Center and in the movement.

6. True Parents, we ask this in sadness for the burden it reveals to you. But we are united in the conviction that such measures are absolutely necessary for the sake of Hyo Jin Nim’s health and well-being and for the continued establishment of True Parents’ worldwide foundation.

7. We also wish to express our heartfelt gratitude for Nansook Nim’s heart and true leadership in being an absolute link between Manhattan Center and True Parents. She has been tireless in working to bring God’s Heart and True Parents’ Standard to M.C.

The letter enraged Hyo Jin, which meant trouble for me. Hyo Jin blamed me for the loss of his position. He dragged me into his room. He took a tube of my lipstick and scrawled the word stupid all over my face. Another time he threw a bottle of vitamins at me, striking me in the head. Knowing how susceptible I was to the cold after childbirth, he once forced me to stand naked at the foot of his bed while he mocked me. I begged him not to beat me anymore. He gave me a choice. I could be hit or spit upon. I think he enjoyed the humiliation he inflicted by spitting at me even more than he had enjoyed hitting me.

The Reverend and Mrs. Moon had suggested that Hyo Jin and I might help our marriage by living outside the compound. Hyo Jin’s reaction had been to remark that the only work I was suited for outside East Garden was prostitution. I knew I could not live with this man, anywhere, under any circumstances. By June I secretly began packing.

My brother called to tell me that there was a house for sale across the street from his in Massachusetts. If I was really serious about fleeing, I would not be alone. I would have family nearby. I cashed in the mutual fund savings I had set aside for the children’s college education and what money I had been saving during my time at Manhattan Center.

They had already been where I was going. Two years earlier, Je Jin had made her own final break with the Unification Church and her parents. She came to East Garden to confront her parents with her grievances about the family, and after an ugly scene with her mother, she left the compound and had never come back. The Unification Church describes Je Jin as living apart from the True Family in order for her husband to complete his studies. That is a half-truth. Jin continues to study but Je Jin no longer speaks to her parents or receives any financial support from them.

My parents had left the Unification Church, too. The fact that those closest to me in my own family were now out of harm’s way made it easier for me to go. There would be no Hongs left behind to be punished by the Moons for my betrayal.

I did not know where to begin legally. My first impulse was to look under “lawyers” in the Yellow Pages. My brother helped me there, too, steering me to lawyers in New York, where eventually I met Herbert Rosedale, a corporate lawyer in Manhattan whose avocation is helping disenchanted cult members and their families. He was a big, balding, kindly bear of a man, the sixty-three-year-old president of the American Family Foundation, a group of lawyers, business executives, and professionals who try to educate the public about the dangers of religious extremism. I knew I needed someone on my side who would not be intimidated by the Unification Church.

Throughout the summer, I talked with my brother and Madelene about how to arrange my escape. I was frightened that Hyo Jin would stop us if I was open about my plans. He had threatened to kill me so many times, and with a veritable arsenal of weapons in his bedroom, I knew he could. I worried for our safety. I was confirmed in my fears one night in the kitchen of the mansion when Hyo Jin came upon Madelene and me having tea. He told her angrily to leave; he ordered me upstairs. When he joined me, he threatened to break my fingers one by one if I continued to pursue a friendship with her. The next day I went to the police to report his threat.

My parents were very supportive of my plans. We had devoted our lives to a cause that was rotten at its very core. I knew that if I did not leave now, I might not live long enough to make this choice again. I was not going to be beaten, threatened, and imprisoned anymore.

My parents were not aware of the extent of physical danger I was in, but were unwilling to sacrifice another daughter to the church. My younger sister Choong Sook had been matched by the Reverend Moon to a man she did not want to marry, the son of a Blessed Couple my parents did not respect. The Reverend Moon had made that match intentionally to punish my parents for their perceived disloyalty.

Choong Sook was a good daughter; she displayed none of my stubbornness or defiance. A cellist, she was an excellent student at Seoul University. My mother was heartbroken at Choong Sook’s fate. She dutifully purchased the wedding garments and gifts for the groom’s family, but her heart was heavy. Another daughter was about to walk a lonely and painful path. She couldn’t do it. After the religious ceremony, but before Choong Sook and her intended were legally married, my parents sent Choong Sook to America to study. She, too, was in Massachusetts, awaiting my arrival. She would not return to Korea or to the husband the Reverend Moon had selected for her.

All that was left was to ask my children whether they wanted to come with me. If they said no, I knew in my heart I would be unable to leave. How could I abandon the children whose love had kept me strong throughout my painful years with the Moons? How could I risk never seeing them again? How could I doom them to a life inside the Moon compound? I held my breath after I told them my plan. My children exploded in excited, puppy-like yelps of pleasure. “We just want to live in a little house with you. Mama,” my children told me through their tears.

None of the children revealed our plans to anyone within or outside of the family, even though it meant not being able to say good-bye to their friends and favorite cousins. They knew what was at stake. They had seen the guns in their father’s bedroom; they had heard his threats when he beat me.

I picked the day we would leave, but it was God who was guiding my choice. True Parents were out of the country and In Jin and her family were away from East Garden. Baby-sitters whispered about my packing, security guards watched me move furniture out of East Garden, but no one alerted the Moons or their key aides. I was frightened but I knew God was protecting us, clearing a path out of East Garden for my children and me.

My brother called from a motel nearby the night before our scheduled escape to tell me that he would be waiting at our prearranged rendezvous early the next morning. From here on in, he said, it was all up to me. And God, I added.

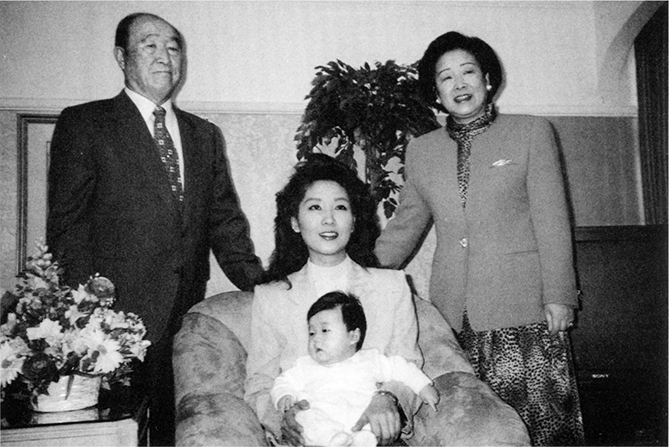

▲ Six months before I fled the Moon compound, I posed with True Mother and True Father on the 100th Day anniversary of Shin Hoon’s birth. Because his drinking and drug use left Hyo Jin in no condition to participate, we went without the traditional 100th Day celebration.

Chapter 10

page 207

My children had insisted that all they wanted was a little house they could call their own. That’s what they got. We moved into a modest split-level in an unpretentious neighborhood of Lexington, Massachusetts, the birthplace of the American Revolution. It seemed like a fitting place to begin my new life. Like the Minuteman whose statue dominates the town green, I, too, had declared my independence from an oppressor.

There is no freedom, though, without security. At my lawyers’ urging, the first thing I did when we reached Massachusetts was file a request with the court for an order of protection to prohibit Hyo Jin from having any contact with me. I could imagine his fury when he had awakened and found us gone. I wanted to do what I could to discourage him from trying to find us.

In my affidavit filed with the Massachusetts probate court, I tried to explain that this was not a typical domestic violence case. I was afraid not only of my husband but of the powerful religious cult that sheltered him. Attempts by any member to break away from the Unification Church are fiercely resisted. What would Sun Myung Moon and his minions do to get his daughter-in-law and five grandchildren back behind the iron gates of East Garden?

The entire legal procedure was intimidating for me, but my fears were eased by the Boston lawyers I had hired with the help of my brother. Ailsa Deitmeyer, an associate in the firm, was especially reassuring, perhaps because she is a woman, perhaps because she is graced with a compassionate heart. She made me feel safe at last.

The court impounded my new address to thwart any efforts by my husband and the Unification Church to contact me. I knew, however, that it was only a matter of time before they learned where I was living. I was a woman with five children, without resources. Where would I go? The Moons eventually would figure out that I had come to my brother; it would not be long before they found me.

I knew that a court order was just a piece of paper, but I thought it might be enough to discourage the Moons from any ideas about taking my children by force. How many custody cases, in circumstances far less bizarre than mine, involve the kidnapping of children?

Standing in the dingy courtroom in Cambridge, I looked past the peeling paint and battered benches. My eyes focused on the American flag. I thanked God I was in America. That flag was protecting me, a Korean girl who had come to this country illegally, who was not yet a citizen. Of all Sun Myung Moon’s sins, I thought, his attacks on America were the most vile. He was rich and powerful; I was neither, but we were equal before that flag. The scales would not have been so balanced in my homeland. For me, on that summer day, the United States meant freedom. The stars and stripes were the most beautiful sight I had ever seen.

After helping me unload the cars, Madelene returned immediately to New York and her job at Manhattan Center in order not to arouse suspicion. Hyo Jin had not guessed her role in our escape. He called her every day to ask if she had heard from me. He ordered her to hire a private investigator with Manhattan Center funds to find me, an order she ignored. When I had not returned or contacted Hyo Jin after a few days, the focus of his demands on Madelene changed.

In a telephone conversation that she recorded, Hyo Jin told Madelene to meet him at the corner of 125th Street and Riverside Drive in Harlem with enough money for him to score some crack cocaine. “I just want to numb this feeling, just do the crack. At least when I do it, I can get lost in it. Maddie, I’m sorry, but I have no other choice. I can’t deal with these feelings… . I don’t want to ask anybody else. Come on, Maddie. Do this one for me. Come on… . I’ve got nothing to lose, Madelene. O.K.?”

The next day Madelene drove Hyo Jin to the airport for his trip to a drug treatment program at the Hazelden Clinic in West Palm Beach, Florida. He spent the ride detailing to Madelene the torture he would subject me to if he ever found me. He described graphically how he would peel off my skin and pull out my toenails. I had good reason to be afraid of him.

He lasted at Hazelden only a few days before doctors asked him to leave, citing his lack of cooperation. The Moons sent him next to California to the Betty Ford Clinic, where he remained for more than a month in their detoxification program. It had taken the loss of his wife and children to force Hyo Jin Moon and his parents to address his addiction to alcohol and cocaine. I knew they would expect me to be heartened by this development, but I knew Hyo Jin too well. He would do what he had to do to appease his parents, but I had little faith that whatever level of sobriety he reached in confinement could be sustained once he returned to East Garden.

My children and I, on the other hand, were drunk on our new freedom. Our house was cramped, our sleeping quarters tight, but we were together, out of the shadow of the Moons. The kitchen was especially small, although that was not an immediate concern, since I did not know how to cook. Meal preparation was one of so many domestic chores I had never learned to do. The staff at East Garden had met all of my daily needs for fourteen years. Chefs, launderers, housekeepers, hairdressers, nannies, plumbers, carpenters, auto mechanics, locksmiths, electricians, tailors, gardeners, dentists, doctors, and dozens of security guards were always on call. I did not know how to run a dishwasher, how to mow a lawn, how to operate a washing machine. The first time the toilet over-flowed, I called Madelene in New York in a panic.

It was a difficult adjustment for me, but it was harder still for my children, who had been treated since birth like princes and princesses. It was not easy for children accustomed to maid service to learn to hang up their clothes, to take out the trash, and to clean up their rooms, but they did. They learned to share bedrooms and wait to use our one bathroom. No longer part of the True Family, superior in status to their peers, they adapted to the new egalitarian realities of their lives and began to make friends as equals.

I had neither the money nor the inclination to send them to the kind of private schools they had attended in New York. Tuition for them the previous year had totaled fifty-six thousand dollars. If I was going to immerse my children in the real world, what better place to start than the public schools? Lexington is a comfortable suburb west of Boston with an excellent school system. I was grateful for that.

My children and I stumbled toward self-sufficiency together.

We had a lot to learn, but we were not alone. My sister and my brother and his wife helped and supported me. Having them close by meant not feeling afraid as we embarked on this new life. The children had their cousins and I had adults who understood the painful and awkward transition I was trying to make. The worries that disturbed my sleep were not the kind a friendly neighbor could easily relate to over a cup of tea.

I had timed our escape so that it would coincide as closely as possible with the start of the new school year. I knew the children would miss their friends, and I was eager for them to be able to make new ones as soon as possible. In September I enrolled Shin June in seventh grade. She would be the only one of my children at the middle school. She was the oldest and the most independent; I was confident that she would do well academically and socially. The other children would all attend the same neighborhood elementary school. The baby would keep me busy at home.

Their teachers reported few adjustment problems and I saw a house full of happy children. Their father had had so little to do with their lives in New York that it was no surprise to me that they felt only relief that he, as well as all the abuse he represented, was absent from their lives in Massachusetts. Shin June played the flute with a local wind ensemble. Shin Gil made friends easily but was very sensitive to being reprimanded, no matter how gently, by me or a teacher. His teacher reported taking him into the hall once when he seemed tearful to ask what was bothering him. “He told me he used to live in a mansion,” she reported. “Now there isn’t much privacy and there isn’t as much to do. He misses his friends. I asked about his dad. He said that once in a while he misses his dad but that his dad was a drunk who yelled a lot.”

Not surprisingly, the first pressure the Moons applied to force us back to East Garden was financial. What savings I had covered our food and basic necessities. My paycheck from Manhattan Center made the difference between being able to pay the monthly mortgage and not. My lawyers had been assured by attorneys for Hyo Jin that those checks would continue to be issued to me until we worked out a temporary child-support arrangement through the probate court.

They weren’t. My lawyers filed a formal request with the court for child support. “It appears Ms. Moon’s check will be withheld, perhaps trying to force her back into an abusive relationship,” my lawyers wrote to church representatives. “Ms. Moon’s decision to seek safety from a horrendously dangerous situation was not reached lightly. Having made the decision, however, she is determined not to return, regardless.”

With my brother’s and sister’s help, I had hired Choate, Hall and Stewart, one of Boston’s finest firms, to represent me in what I anticipated would be a protracted divorce case. We knew I would need the best lawyers in the city if I was going to take on the Moons. Like so many women facing divorce, I had no idea how I would pay my lawyers. In a study on gender bias in the courts in 1989, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court had concluded that “there is too little legal help available to moderate income women, in part because judges fail to award adequate counsel fees, especially during the pendency of litigation.”

My chief lawyers were a brilliant Boston Brahmin named Weld S. Henshaw and his skilled and empathetic associate Ailsa De Prada Deitmeyer. They were confident that the court would require Hyo Jin to pay my legal bills. As experienced as he was, Weld conceded he had never encountered a divorce case quite like mine. Hyo Jin Moon was not the typical defendant; determining his real assets would not be a simple matter.

Hyo Jin retained law firms in New York and Massachusetts, including the Manhattan firm of Levy, Gutman, Goldberg and Kaplan. Gutman was Jeremiah S. Gutman, the former head of the New York Civil Liberties Union, the man who had championed Sun Myung Moon’s cause when he was convicted of tax evasion in 1982.

Our case was assigned to Massachusetts probate court judge Edward Ginsburg. He was a fair-minded gentleman, nearing retirement, who ran his Concord probate courtroom in a firm but folksy manner. Something of an eccentric, Judge Ginsburg was easy to spot arriving for work on summer mornings. He was the fellow in the blue seersucker suit with the yappy blond poodle on a leash. His dog, Pumpkin, accompanied the judge to the courthouse every day.

No sooner had I asked the court to require Hyo Jin to support his children than I heard from the Moons directly. Money was a great motivator. In Jin sent a letter through my attorneys to urge me to drop my legal action and come home. She enclosed an audio tape from Mrs. Moon, making the same plea.

It was startling to hear Mrs. Moon’s voice in my new surroundings. She could not hide her anger, but she made attempts to sound caring and to be distraught at my departure. The True Family needed to be intact. The bottom line, as always, was that I was at fault. “Nansook, your behavior is not acceptable to all the people who love you.” She predicted that I would be condemned by many people in the future and urged me to return “… without being changed.” [Mrs Moon wanted me to change my behavior and return.]

It struck me, as it always had, how selective the Moons could be when applying the teachings of the Divine Principle. No one lived her belief in forgiveness more openly than I. Hadn’t I forgiven Hyo Jin when he left me for another woman weeks after our wedding? Hadn’t I forgiven Hyo Jin when he gave me herpes? Hadn’t I forgiven Hyo Jin when he took up with prostitutes? Hadn’t I forgiven Hyo Jin when he squandered hundreds of thousands of dollars that had been intended for our children’s futures? Hadn’t I forgiven Hyo Jin when he beat me and spat upon me? Hadn’t I forgiven Hyo Jin when he abandoned me and our children for a life of drug and alcohol abuse? Hadn’t I forgiven Hyo Jin when he took a lover on the day I brought our newborn son home from the hospital?

I was not the one who had failed to consider the consequences of my actions. I had spent fourteen years refusing to entertain the idea that I could leave Hyo Jin Moon, that I could make a claim to a life free of fear and violence. I had not left East Garden precipitously. I had tried mightily to make my marriage work. Had the Moons ever thought that it was them, not I, who could be wrong?

In Jin’s letter was similar to Mrs. Moon’s tape in its judgmental tone. She expressed sympathy for my situation but scoffed at my seeking a restraining order against Hyo Jin, a man who had beaten, humiliated, and threatened me for fourteen years. She accused me of exaggerating the claims in my restraining order that I feared for my life. But her major point was apparently to try and convince me not to use the legal system against the Moons.

She hinted that it would be easy to attribute dark motives to my decision to leave. “Some have even commented that you left your husband after all these years only because he had lost his job and his position in the family,” she wrote. I could only convince the family of my good intentions by returning and helping Hyo Jin confront and conquer his alcoholism and drug abuse. “You are hurting everyone who loves you by using the legal system to get what you want,” she said, describing the system as “adversarial” and the end result as hurt for everyone.

It was impossible for the Moons to understand that I had already been hurt. I did not want a reconciliation; I wanted release from the abuse of a violent husband and the hold of a religion that had already consumed twenty-nine years of my life. I had never felt a stronger presence of God in my life than at the moment when I decided to flee East Garden. He had lifted the veil from my eyes; I was seeing clearly for the first time. I would never go back.

On October 25, the court ordered Hyo Jin to make monthly support payments for the children and appointed a social worker, Mary Lou Kaufman, to investigate whether visits with their father were in the best interests of our children. I did not want to deprive my children of contact with either their dad or their grandparents. However problematic the relationship, there was no question in my mind that children deserve two parents and two sets of grandparents. I knew that Hyo Jin loved our children, as much as a man as self-absorbed as he could love anyone. However, I urged Ms. Kaufman not to permit visits until the children were more settled and there was demonstrable evidence that Hyo Jin had stopped abusing drugs and alcohol.

I was especially adamant about confirming his sobriety. Hyo Jin prided himself on his ability to circumvent the law. He had once substituted a sample of Shin Gil’s urine for his own during a drug test mandated by his drunken driving conviction in New York. It was also noteworthy to me that Hyo Jin had not even asked to see his children until after I applied for financial support.

Ms. Kaufman met Hyo Jin in her office for more than four hours over two days in November. In her report to the court, she noted that he was anxious and highly agitated. He had a dry mouth and was hyperventilating. She suspected he was high on cocaine. He laced his speech with obscenities. He told her that my parents were behind the divorce effort, that my mother had proclaimed herself the Messiah, and that my parents intended to use whatever money I got in a divorce settlement to establish their own church in Korea. He brought my uncle, Soon Yoo, to support this cockamamy theory. Soon, who had been instrumental in my mother’s joining the church, betrayed her to improve his position with the Moons.

Hyo Jin insisted to Ms. Kaufman that he had always been an involved and active father, but he could not tell her the ages of our children or what grades they were in at school. He insisted that if they were not clamoring to see him, it was only because I had poisoned their minds against him. He was shocked to hear that Shin Gil had asked for a picture not of his dad but of one of his toys.

She concluded in her report in early December that no visitation should be allowed between Hyo Jin and the children until Hyo Jin had demonstrated that he had been free of drugs and alcohol for a two-month period.

The children and I were busy preparing for our first Christmas in our new home. My parents were coming from Korea. It had been years since we had all been together. Our reunion would be a celebration of our freedom as well. We decorated the house with the children’s drawings from school and a six-foot Christmas tree.

The Saturday before Christmas, I responded to a deliveryman’s knock at the front door. My heart raced as I accepted a package with a familiar return address. Hyo Jin had found us. I tried to conceal my concern from my parents and my children, but I had become less adept at disguising my emotions since leaving the Moon compound. The package contained several small Christmas gifts for the children and a card addressed to me in Korean. In it, Hyo Jin alluded to my revelations about his substance-abuse problems in court documents and asked how I would feel if my own “nakedness” were exposed to the world. It was a veiled threat to expose a videotape he had made of me in the nude.

My father, noticing my distress, tried to comfort me. “Don’t let him get to you,” my father advised. “If you’re down, he’s succeeded in his goal to hurt you.” He was right. I had done nothing wrong. Hyo Jin had. His letter was a criminal violation of the restraining order that prohibited him from contacting me. The son of Sun Myung Moon still thought he was above the law. I reported the threat to the police. Hyo Jin was charged with a criminal offense.

Through my attorneys, Hyo Jin sent letters to the children, expressing his love for them and his desire to see them. He could not resist criticizing me, however. In his letter to Shin June, he wrote: “Of course I feel angry at times at your mother but I want to forgive her. There are a lot of things you don’t know about your mother but that’s not important. You know why? It is because I want you to be a loving person who can love someone forever and not give up on the person that you love and also learn to forgive them as they face trials that life will offer, as it offers to everyone.”

To Shin Ok he wrote that he knew she loved him. “If there was no one telling you how bad Dad is I truly think you would never think even for the moment that way. You know what? Even if you think Dad is bad I feel OK because I won’t be bad any more.”

He promised all the children that he would write to them again soon but he never did.

In February 1996 Hyo Jin met again with Ms. Kaufman to assess the wisdom of allowing visits with the children. He was outraged that he had been barred from seeing them for so long. He talked about the revenge he would seek against me in court. He told Ms. Kaufman he would hire “a cutthroat legal firm from New York” to ruin me financially. He was attending meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous, he said, and was now committed to a life of sobriety.

Ms. Kaufman granted supervised visits with the children that spring. Hyo Jin saw his children only twice before the man who insisted he had changed forever failed a drug test. Visits were suspended until Hyo Jin could prove to the court’s satisfaction that he was no longer abusing drugs or alcohol. That day still has not come.

For all his accusations of being denied contact with his children, Hyo Jin has made no effort to stay in touch with them. His letters, to be delivered through my attorneys, were encouraged by the court, but he never wrote to them. He does not send them cards or gifts on their birthdays or at Christmas. He does not inquire how they are doing in school.

As troubling as their memories of their father are, his abandonment of them is painful for our children. Shin Gil, the favored son now living on my limited income, especially remembers how his father indulged him at video arcades and with expensive toys. Shin Hoon, the baby who never knew his father, wonders where he is. When I take him to nursery school, he often asks, “When is my daddy going to pick me up like the other kids’?”

Divorce is never easy for children, but for a man who claims to be part of the True Family, the embodiment of traditional moral values, Hyo Jin Moon has made it much more difficult for our children than it needed to be.

The Moons did not always pay the court-ordered child support. When they did, the check always came late and only after reminders from my lawyers, who were billing me for more hours than I could ever hope to pay. I had to sell some of my jewelry one month to pay routine expenses. Hyo Jin’s position was that he could not pay my legal bills because he had no source of income. He had been fired from Manhattan Center and cut off from the True Family Trust. He asked the court to believe that the son of one of the wealthiest men in the world was destitute.

Judge Ginsburg was not buying it. The lines between Unification Church funds and Moon family money and Hyo Jin Moon’s finances were imaginary. Hyo Jin had access to limitless funds while reporting few assets and only modest income. In terms of housing, travel, cars, private schools, and servants, he and his siblings lived without any budgetary constraint. For Hyo Jin to argue that he had no money because he was unemployed was to ignore the fact that his employment at Manhattan Center Studios had been no more independent of his father than his living arrangements. His father housed him, fed him, and employed him. Take away the Unification Church and the uneducated Hyo Jin Moon was unemployable. It was laughable to suggest that whatever assets he had, and he claimed he had few, had been acquired in any way other than through the largesse of Sun Myung Moon.

To maintain the fiction that Hyo Jin was destitute, one had to ignore that all his income led back to the same source: Sun Myung Moon. Noting the fine cut of the suits being worn by the army of attorneys from Boston and New York who accompanied Hyo Jin Moon to court, Judge Ginsburg ordered him to pay my counsel fees or face arrest for contempt of court.

The Moons would not pay. That summer Sun Myung Moon sponsored an international conference in Washington, D.C., to discuss how to restore traditional family values. The irony was almost too rich. Hyo Jin Moon could not attend the two-day symposium in the Great Hall of the National Building Museum to hear speakers such as former presidents Gerald Ford and George Bush, former British prime minister Edward Heath, former Costa Rican president and Nobel Peace Prize winner Oscar Arias, and Republican presidential hopeful Jack Kemp address the erosion of family values around the world. Sun Myung Moon’s son was languishing in a Massachusetts jail cell, where Judge Ginsburg had sent him for defying his order to pay my legal bills. He would remain there for three months, winning his release only after he formally filed for bankruptcy in New York State to prove that he was a man without financial resources.

Money became a constant source of worry for me. What if the Moons did not send the check? What if my lawyers got tired of waiting to be paid? How would I care for my children? I had an undergraduate degree in art history. I wasn’t qualified to do anything more than volunteer as a tour guide at the Boston Museum of fine Arts. That would not pay the dental bills for five children. In my desperation, I applied for a sales position at Macy’s department store at the local shopping mall. I completed the training course by asking my sister and Madelene to baby-sit. Madelene had left the church one month after I did and moved close by. I could not have gotten through my first year of freedom without her and my sister and brother. Only when I was trained did I learn that Macy’s expected me to work every weekend. How could I? Who would watch my children? I returned home, feeling defeated.

Independence has its price. I needed to settle my divorce case and move on with my life. I would need more education if I was going to land a job that would allow me to give my children the advantages they deserved, advantages their cousins in East Garden took for granted.

Through my attorneys, I proposed a divorce settlement that would sever my ties forever to the family of Sun Myung Moon. I asked that trust funds be established for me and for my children from which I would pay for our health insurance, education, clothing, housing, and all other expenses. There would be no alimony and no child support. I would pay my own legal fees. My lawyers summarized my intentions in the proposal:

“The concept of a trust such as this would insure there was no likelihood of these assets being dissipated so that the settlement could truly be finished now and forever with no second chances.”

Sun Myung Moon refused. He was firm that Hyo Jin’s financial situation was independent from his own. He would not take responsibility for the future well-being of his grand-children. In addition, the Moons demanded that the terms of any divorce agreement remain confidential. They did not want me to talk. I refused all demands for confidentiality.

In a deposition filed with the court in July 1997, Sun Myung Moon made his position clear.

When my son, Hyo Jin Moon, was cut off as a beneficiary of the True Family Trust and was discharged from his position as an employee, officer and director of Manhattan Center Studios, Inc. and was subsequently discontinued from his status as a disabled employee receiving disability payments from Manhattan Center Studios, Inc. my concern and love for his five children, my grandchildren, moved me to provide support funds fixed by order of the court in Massachusetts having jurisdiction of the dispute between my son and his wife.

My son, Hyo Jin Moon, had and has no control over whether I choose each month to make and continue to make such payments. They are voluntarily made by me so long as I am able and willing to do so.

Negotiations have broken down and I now learn that my daughter-in-law is making efforts to re-incarcerate my son, despite the fact that he has no assets or income other than a $3,500 gross salary per month from his re-employment by Manhattan Center Studios, Inc. I am re-thinking the situation.

The implied threat, that if I did not settle on the Moons’ terms, child support payments would be cut off, was not subtle. The Reverend Moon paid fifty-thousand dollars toward my counsel fees to keep his son out of jail, not out of respect for the court that ordered the bills paid.

“I am pleased that Hyo Jin Moon has recovered sufficiently to resume his productivity as a producer of musical recordings and I hope he will be able to continue to be artistically creative and productive and to earn sufficiently so that I can discontinue supporting him as I have consistently done since he was cut off from all income,” the Reverend Moon said, still ignoring the reality that Hyo Jin’s job only existed because his father created it.

Our divorce case had produced enough paper to make a stack of legal documents two feet high. It had dragged on for two and one-half years. Sun Myung Moon had displayed more willingness to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to lawyers than to guarantee the future security of his grandchildren. So much for family values.