Updated July 10, 2021

In the 1990s South Koreans began criticizing Japan for its comfort women system in World War II, but have hardly said anything about its own comfort women system, which begs the question– “If Koreans thought the Japanese comfort women system was so bad, why did the Korean Government set up a similar ‘comfort women’ system, with hundreds of thousands of prostitutes, for UN soldiers after the Japanese left Korea?”

The Korean government was registering women to be prostitutes for UN soldiers stationed in Korea. The US military attended Korean police run training courses for the prostitutes.

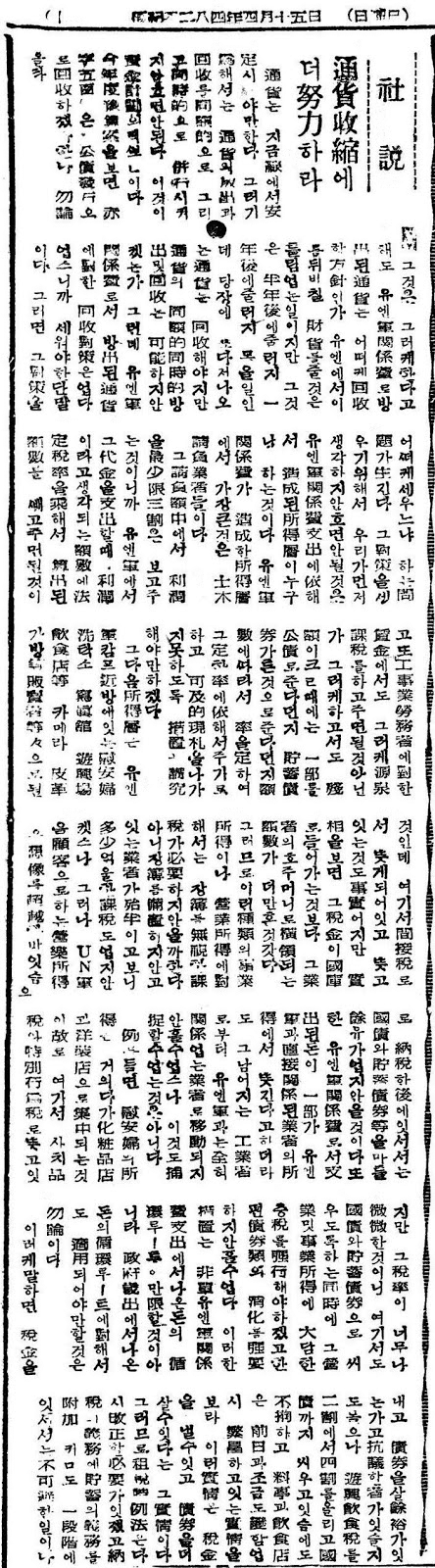

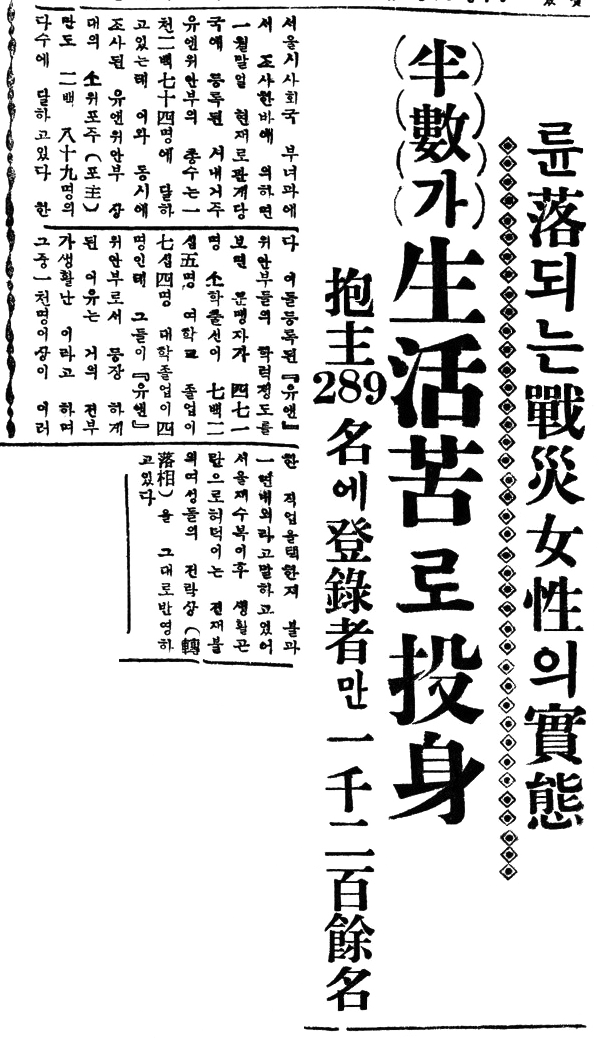

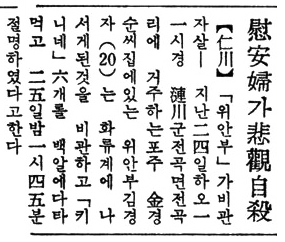

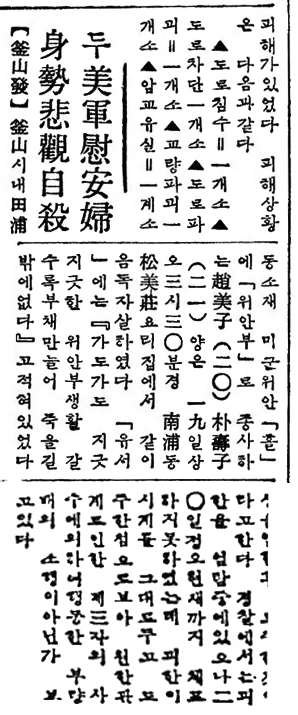

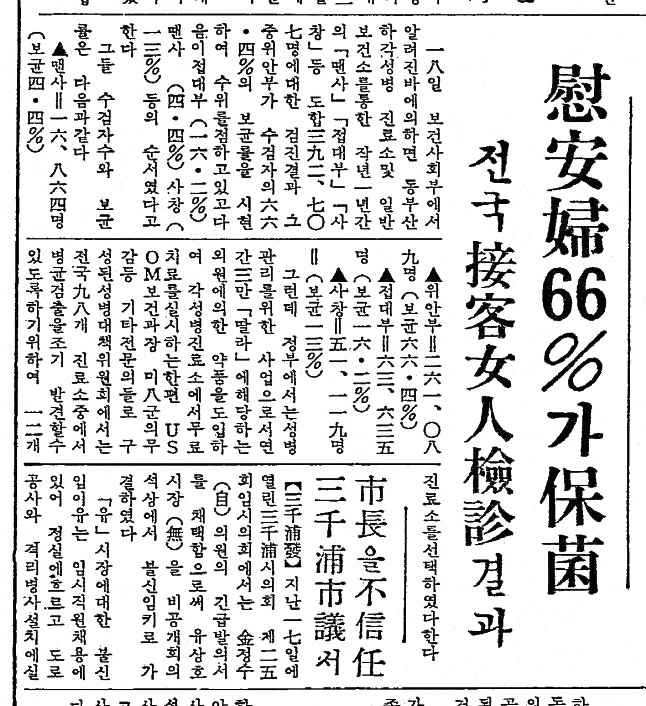

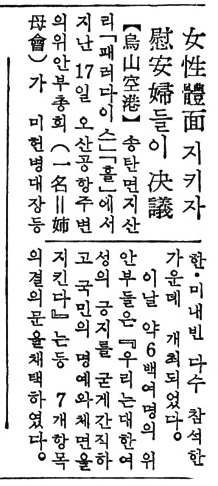

One 1959 article below mentions Korean 261,089 comfort women – which is evidence that Korea had a significant number of comfort women. At one time 66% of them were infected with a veneral disease.

Contents

1. Meet Miki Dezaki, Director of the film, Shusenjo: The Main Battleground Of The Comfort Women Issue.

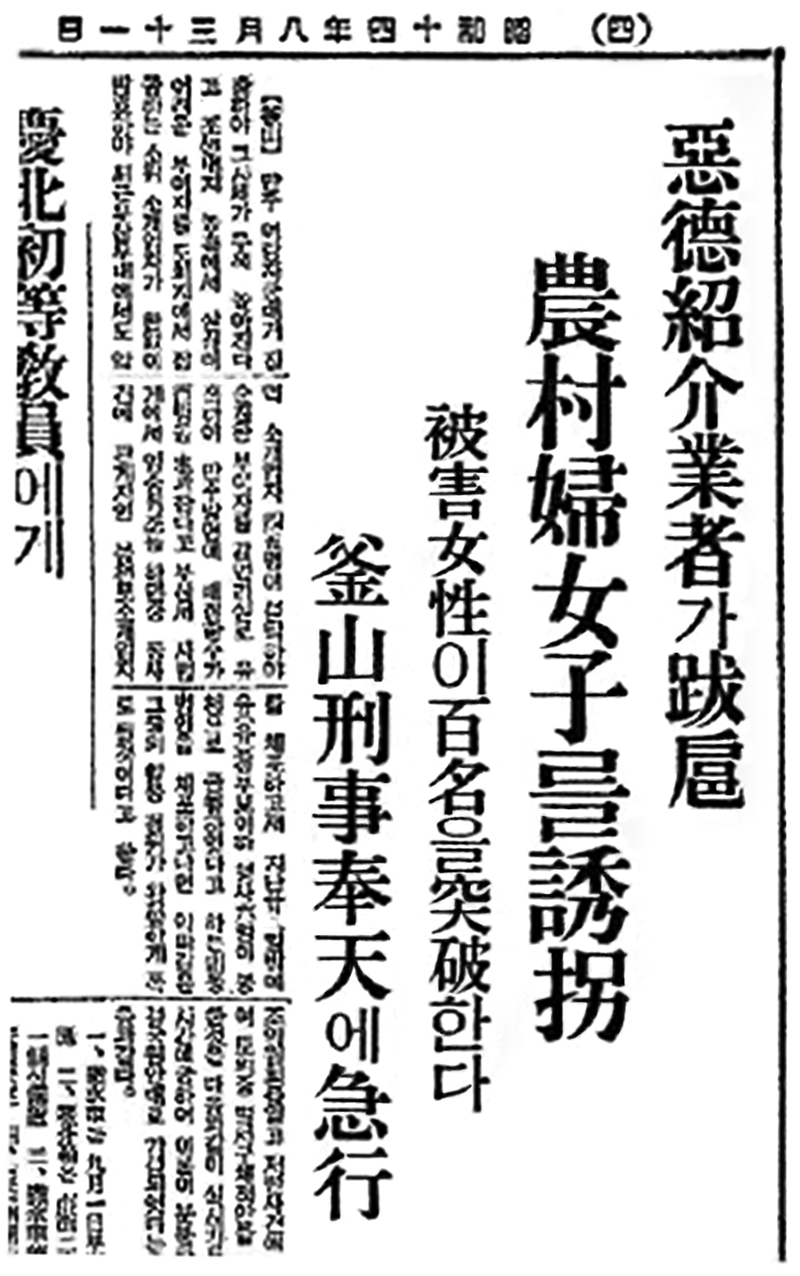

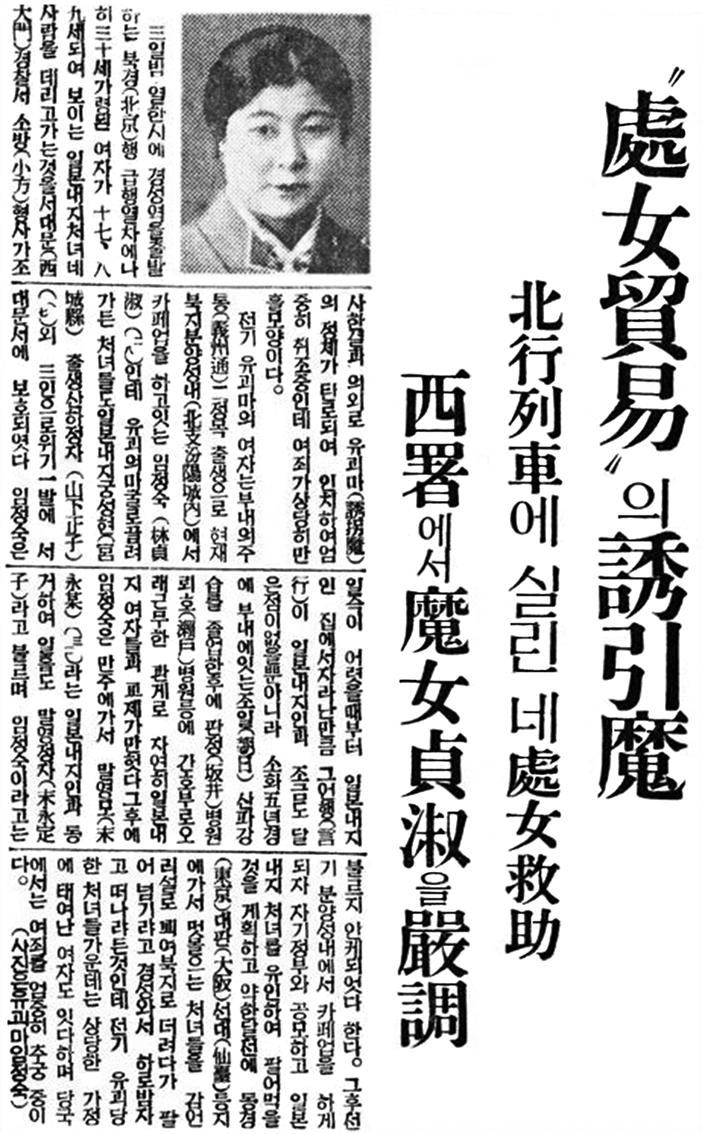

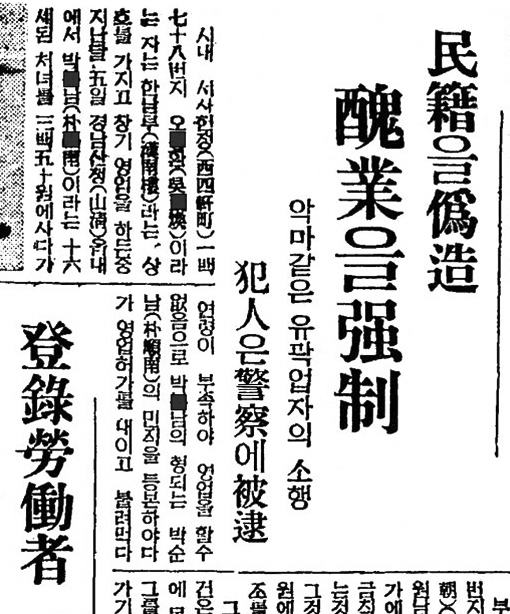

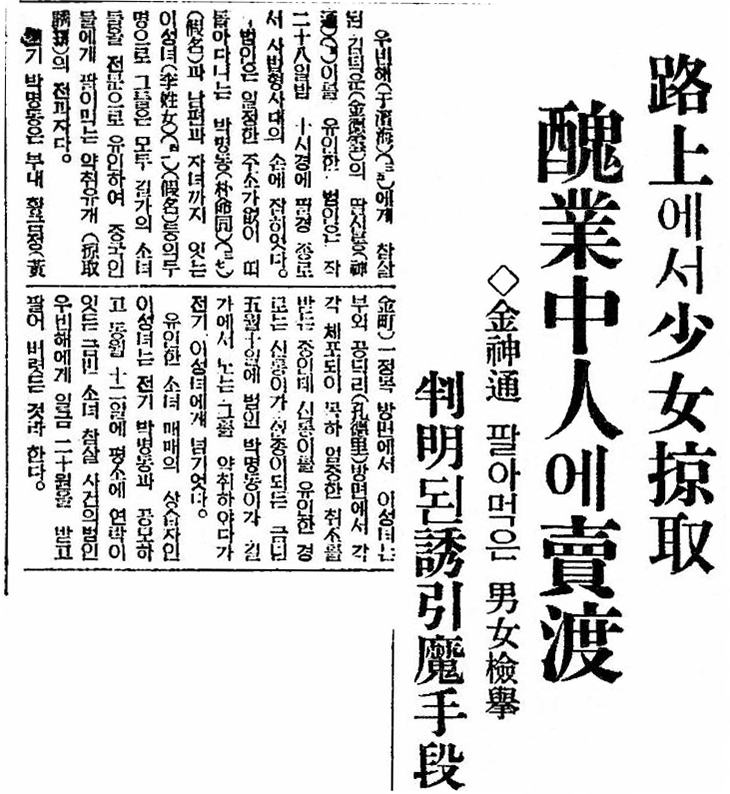

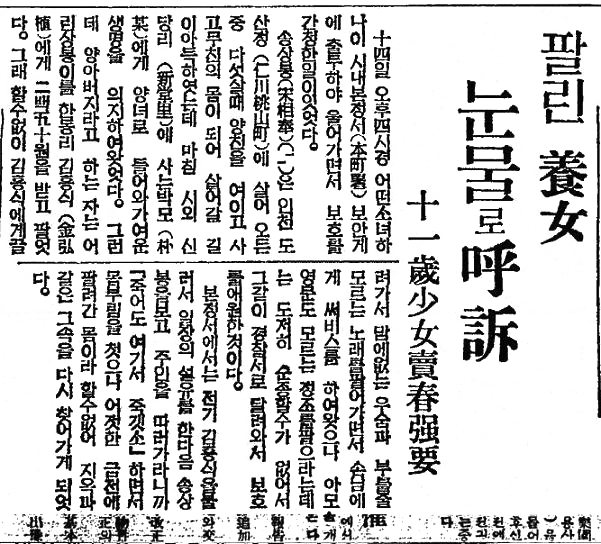

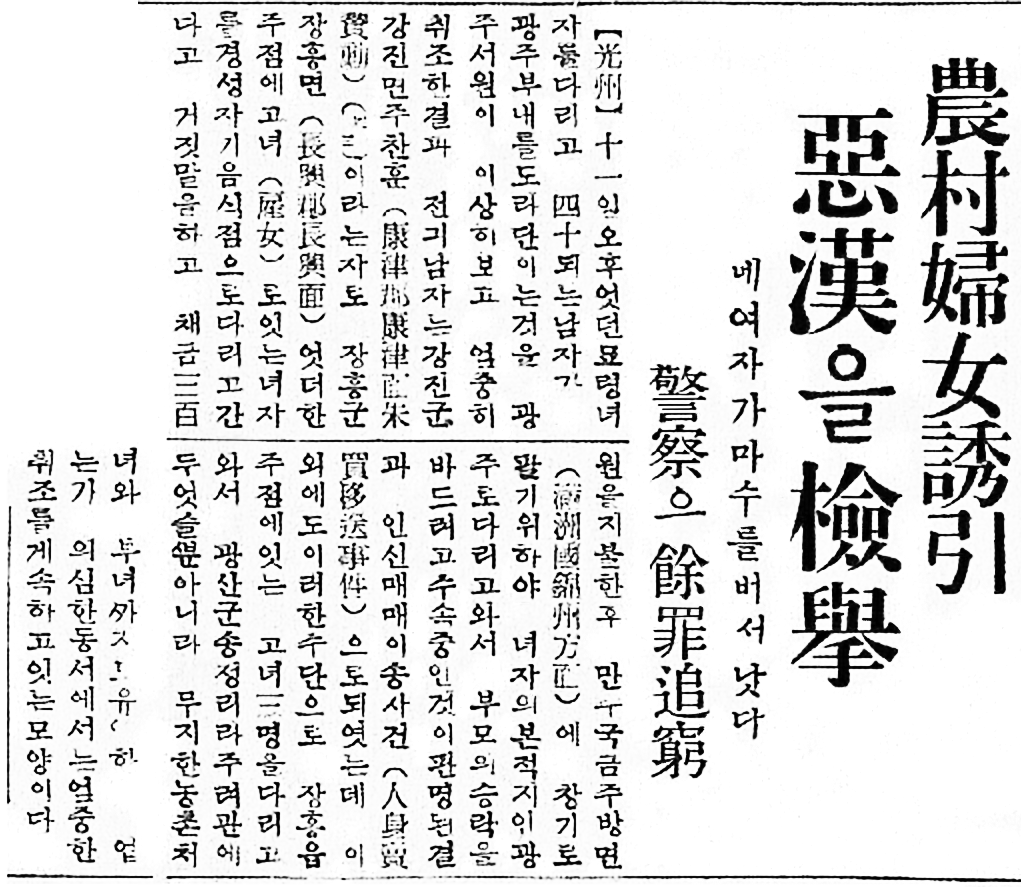

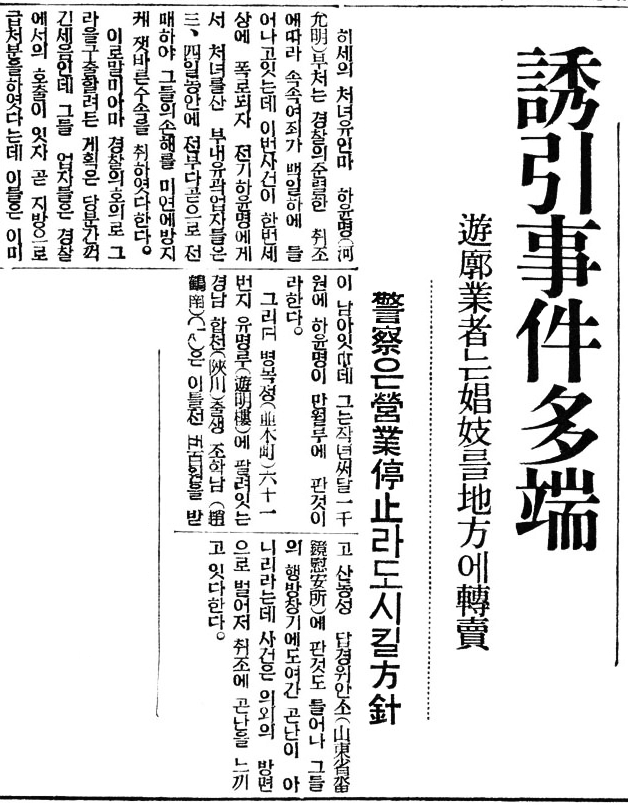

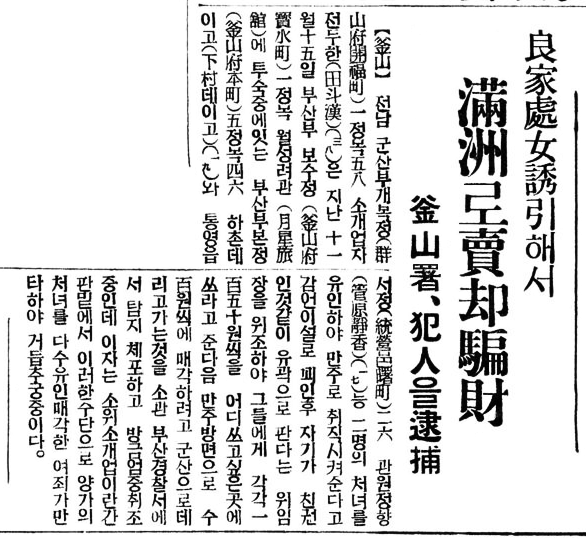

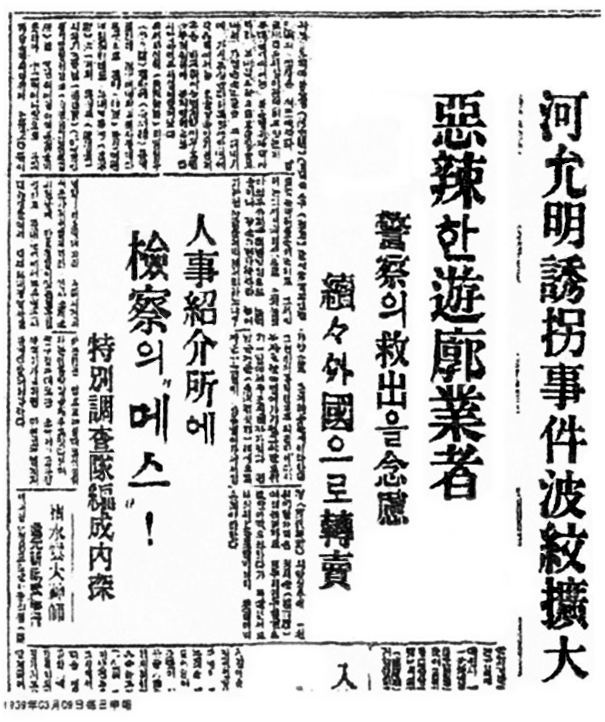

2. Thousands of Korean men and women tricked, kidnapped or forcibly abducted Korean girls to be ‘comfort women’. Statistical Yearbook of the Governor-General of Korea, from 1931-1943.

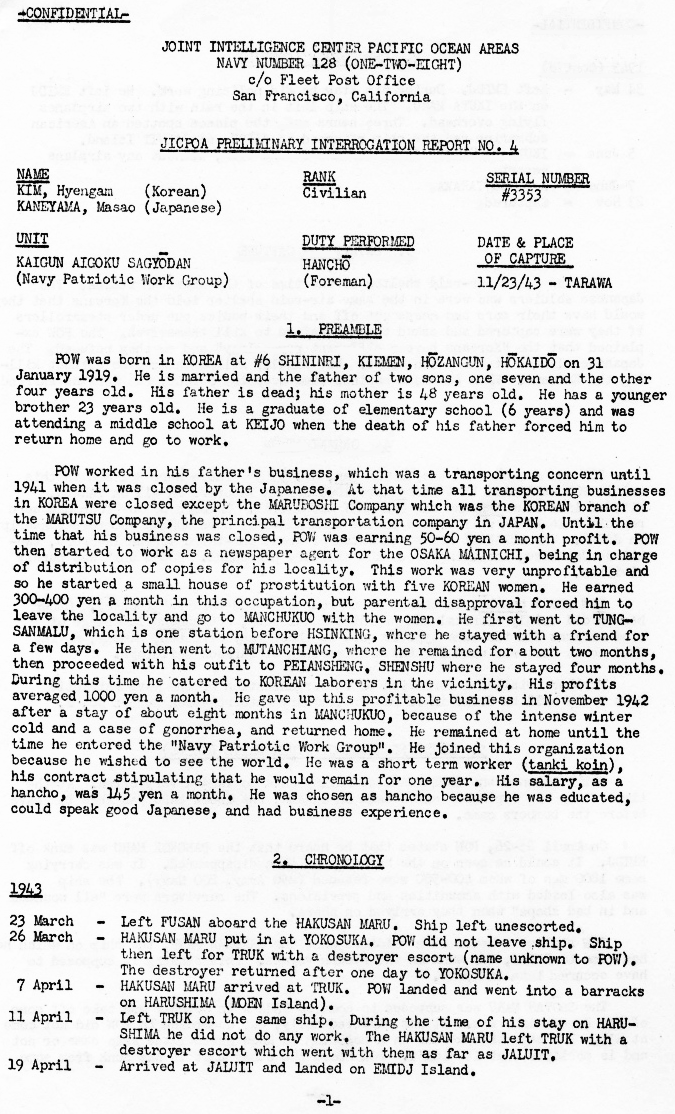

3. U.S. military documents featuring Korean POW testimony discovered at U.S. National Archives

4. Korean testimony documents highlight ethnic and gender discrimination under Japanese colonial rule

5. “The Comfort Women” (2008) book by Professor C. Sarah Soh (352pp)

6. “Comfort Women of the Empire” the battle over colonial rule and memory (2014)

帝国の慰安婦 植民地支配と記憶の闘い by Professor Park Yu-ha, 박유하, 朴裕河 (336pp)

7. Mun Ok-chu’s memoir

8. Chart of Comfort Station managers, revealing almost all were Korean

9. The Korean comfort station manager’s diary

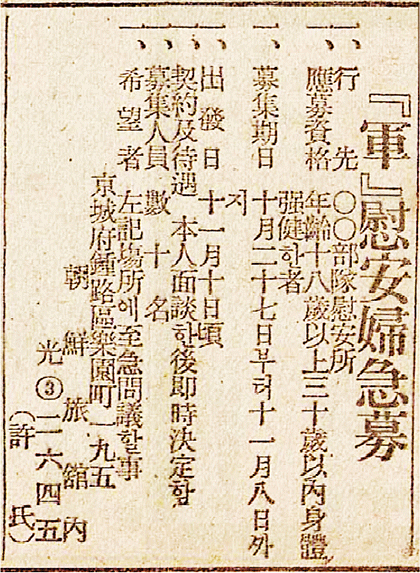

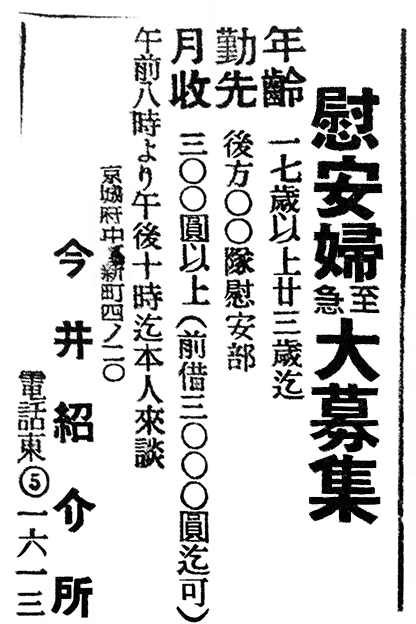

10. Comfort Women Urgently Wanted – Ads in 1944 Korean newspapers

11. Comfort Women rescued by Japanese military police

12. Kim Tŏk-chin was recruited by Koreans at 17 to be a ‘comfort woman’

Various historical documents and oral histories

13. In 1965 Japan gave $800 million as reparations for Korean occupation

14. Military commentator Ji Man-won raised “fake comfort women” question

Footnotes

1. Professor C. Sarah Soh interviewed at SFSU in 1999

2. Extract Human Dignity and Sexual Culture: A Reflection on the ‘Comfort Women’ Issues by Professor Soh

3. Behind the Comfort Women Controversy: How Lies Became Truth by Professor Nishioka Tsutomu

4. The “Comfort Women” Issue and the Asian Women’s Fund.

5. GSOMIA lives, but what’s next for Japan and South Korea ties? – Japan Times

6. A few more of the hundreds of Korean newspaper reports on the continuous fight against Korean men and women who lured Korean (and Japanese) girls and women into prostitution. There were many arrests of traffickers and hundreds of girls were released.

7. Ex-Prostitutes Say South Korea and U.S. Enabled Sex Trade Near Bases in Korea.

8. Prostitution in Korea after the Korean War, including many newspaper articles from the time.

9. Professor Cho Heung-guk on “The problem of ‘Lai Tai-han’ – The children born between South Korean soldiers and Vietnamese women during the Vietnam war, and a second wave who have been born since diplomatic relations were established between the two countries in 1992. There are estimated to be between 5,000 and 30,000 from the era of the Vietnamese war and they were almost all abandoned.

Here is an article from 1925

This May 11, 1925 article is from the Korean newspaper Dong-A Ilbo and is entitled, “Local Color.” The reporter is describing the Korean city of Cheongjin in North Hamgyeong Province.

Local Color

If you walk down a Korean street in this city, the first thing you notice after one or two houses are signs that say “Boarding House,” “Restaurant,” and “Pawn Shop.” And in every alley you see places with such names as “Seoul House” and “Daegu House” that sell rice wine. You also see many prostitutes in heavy makeup going in and out the doors. However, rather than seeing these establishments as promoting immorality, I see them as places that necessarily exist to provide natural, temporary relief to an increasingly large number of laborers.

Speaking of prostitutes, scores of Korean and Japanese bordellos fill Bukseong-jeong (part of the port city of Cheongjin in Northern Hamgyeong Province ) and have become the town’s specialty product. Whenever military ships, which allow no women onboard, enter the port, it is said that dozens and dozens of sailors race ashore, completely turning the port into a “City of Flesh.” Even when there are no military ships in port, it is said that the streets are bustling with nightlife as sailors are always coming and going.

Most of the buildings along the street are Japanese style. Many of the people on the streets wear Western suits. Hundreds of people leave and enter the city each day. Even many of the locals seem to be wearing Western suits. You hear auctioneers shouting, “five cheon, ten cheon,” and you also hear, “Let’s play, let’s play.” You hear, “The Social system is blah, blah, blah,” and you also hear, “Amen.” All parts of the new and old worlds are represented on the streets of this city.

VIDEO: Meet Miki Dezaki, Director of the film, Shusenjo: The Main Battleground Of The Comfort Women Issue.

An interview with the director of ‘Shusenjo’, a film about the Japanese army’s sexual slavery of women during the 1930s and 40s.

Miki Dezaki, is a Japanese-American. He was a monk in Thailand for a year, and is a former graduate student who edited this film in his dorm house in Tokyo.

Transcript (slightly edited to improve readability)

1:00 Interviewer 1: “… and how you tried to really show those different voices in a very non-judgmental way. What was the trigger for getting interested in this issue?”

Miki Dezak: “I have friends both in Korea and in Japan and I noticed that when they talk to each other about historical issues they always get in arguments all the time. And when I actually started researching the ‘Comfort Women’ issue I realized that there is a huge gap in information between what the Koreans know about the ‘Comfort Women’ issue and what the Japanese people know. Koreans and Japanese people just think the other side is irrational and is [being too] emotional. Through my film, hopefully people can realize that there is a reason why Koreans are angry and there is a reason why Japanese people don’t know a lot about the ‘Comfort Women’ issue. And maybe it’s not the best solution to just get angry at each other but maybe through [a deeper] understanding they can have better discussions [together].”

1:56 Interviewer 1: “OK, so one of the recent issues has been over the ‘GSOMIA’ (General Security of Military Information Agreement) [see link to Japan Times article below].

Miki Dezak: “I think the first move was by Abe, to be honest. He took that forced labor verdict and turned it into a diplomatic issue, whereas it was really a human rights issue it’s a civil case. And then Korea, the people retaliated by boycotting – which I thought was a really great move – it showed the people power thing. Unfortunately, I knew that it was going to be spun in Japan – ‘Oh, Korea is being irrational again’. Now I think this retaliation by President Moon is also going to be seen as that. Prime Minister Abe likes to create an enemy, to foster more and more ill sentiment towards each other. He gains more support that way. His main goal is really to change the [Japanese] constitution so they can remilitarize. So now we have a destabilized region. Now people in Japan might be like, Oh, OK, maybe we do need a military now.

3:11 Interviewer 1: “It was changed to ‘No Abe’”

3:16 Miki Dezak: “That is a good kind of approach to differentiate between Japan as a whole and Abe. When you say ‘No Abe,’ or we don’t agree with Abe’s policies, actually Japanese people can get behind that as well. So Korean and Japanese people can support that; [both] don’t agree with Abe’s policies.”

Interviewer 1: “It’s very dangerous to generalize too much.”

Miki Dezak: “Yeah, yeah”

Interviewer 1: “What was the key message you wanted to [get across]?”

Miki Dezak: “I would say for the Korean audience, be aware of the information that they haven’t received. They have heard a lot about the ‘Comfort Women’ issue, in the news and in the media, but what was the information that was left out, and why was that left out? The Korean media oftentimes tends to focus on the most extreme cases.”

4:10 “A lot of Koreans think that Japan has never apologized, but that actually is not true. They actually apologized many, many times. I wouldn’t say that the apologies were full apologies. But some of them, especially in the 1990s, were actually quite sincere. In the Kono Statement they really acknowledged the ‘Comfort Women’ system and Japan apologized and promised to teach the history of the Comfort Women. Now they have kind of gone back on that because they don’t teach it very much anymore.

So it is interesting, Japanese people and the media basically say ‘You can’t really trust Koreans because they backed out of the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement’. Basically Japan has backed out of the Kono Statement by not teaching the history of the ‘Comfort Women’ – but they never talk about that in the Japanese media.”

Interviewer 1: “I think in Germany, for example, after the apologies of Brandt or other people, they continued to produce common textbooks between the German, French and Polish people and taught about the [problematic things that were done during World War II]. The apology is only the first point and it is the point of departure to develop friendly relationships with other countries. But in Japan, for example, the Abe government have erased [the problematic things of World War II]. You have the Kono Statement, and then what comes after it?”

Miki Dezak: “Right, exactly. Since the Kono Statement there was a huge movement to erase the [problematic] history.”

Abe video clip

5:40 “Actually even Abe says, ‘Oh we uphold the Kono Statement’ – every year, basically. It’s really strategic, I think. When he says he upholds the Kono Statement, that tells the Japanese people, Oh OK, we’re doing the right thing, but in the background he is saying, take down the statues, we don’t teach the ‘Comfort Women’ issue.”

6:05 Interviewer 2: “Why do you think they are doing this? Why do they try to erase [parts of] the history?”

6:11 Miki Dezak: “There are two ways to look at patriotism. Actually a lot of the left-wingers in my movie say they do what they do because they love their country. They want it to get better. They want to see the horrible things that they have done in the past, and to reflect on them and then to get better as a country. Whereas the right-wingers, the nationalists, see patriotism as like you deny all those horrible things and you believe this kind of myth that Japan is superior and amazing and honorable.”

6:44 Interviewer 1: “I once had an interview with Professor Hosaka Yuji. He mentioned that one of the reasons why Japan does not apologize, or is inconsistent with its apologies, is to a certain extent because they have a ‘Samurai mentality’ [meaning] that you don’t actually give in. So in Japan, for example, when they lost World War II, 500 war criminals actually went into a room and committed suicide. Giving in and saying we made a mistake and we’re really sorry to a certain extent shows weakness. Do you think that is true?”

7:15: Miki Dezak: “I think it is hard for Japan to give in when they feel superior to Korea. People say if you apologize for the ‘Comfort Women’ then you have to apologize for the forced labor, then maybe you have to give up the islands [between Japan and Korea that are claimed by both sides]. But I think those situations are all very different. You could still apologize for the ‘Comfort Women’ issue and not necessarily apologize for the forced labor because the forced labor was not necessarily a government run system. It was more private companies that did that kind of forced labor. Their view of history is that Japan has never done anything wrong. They were not the aggressors in the war; they were defending themselves and liberating Asia. So that is why, I think, it’s really hard [for them] to apologize.”

8:05 Interviewer 1: “How was the reaction to your movie in Japan? Aren’t you afraid?”

Miki Dezak: “There is always a big concern because I criticize these huge powerful people. So these days when I walk around in Japan I [go] in disguise. But surprisingly though, the reception to the film has been very good. They show that they are not going to give in to these right-wingers any more.”

Quote: “These people are historical revisionists or denialists.”

8:45 Interviewer 1: “We have them in Germany as well. Holocaust denialists and everything.”

Interviewer 2: “I didn’t know there was actual organization in these groups who just yell about it. But do they actually have seriously funded organizations?”

Miki Dezak: “Yeah, of course they have a lot of funds. I think the difference between Japan and Germany is that denialism is actually illegal in Germany. You can’t do these things. And if there are denialists, they are a very small group. Whereas in Japan, denialism or historically revized history about the ‘Comfort Women’ issue is mainstream. That is what most people [in Japan] know about the ‘Comfort Women’ issue. My Mom used to think that way. (People who) don’t really know about the ‘Comfort Women’ issue, they just accept what the media has said to them, which is the right-wing perspective.”

9:35 Interviewer 2: “The ‘Comfort Women’ issue is a human rights issue, which is an international issue.”

Miki Dezak: “For sure”

9:41 Interviewer 2: “I think that sums up everything so well.”

Miki Dezak: “It is a symbol, right. Then in which direction are we going as a global community? So if you can’t give these women their justice, then we are really going backwards in time.”

10:02 Interviewer 2: “As a foreigner living in Korea I am sometimes confused if I am allowed to talk about anything that has to do with the history that has happened here. I heard that man say it and it made me feel more comfortable, and it gave me encouragement, and more power. [I think] people should talk more about this.

Miki Dezak: “I hope Korean people do not see this as Japan versus Korea. It’s actually people who support human rights versus those who are trying to deny those rights.”

Several important books have been written about the Comfort Women issue, and there are many historical documents from the 1930s and 40s. Statistics from Korea are very revealing:

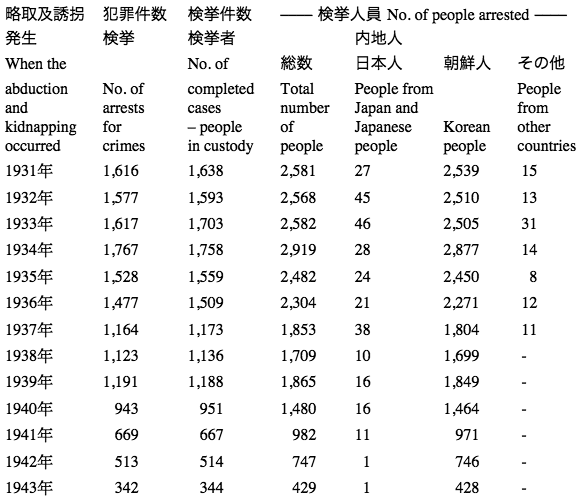

Thousands of Korean men and women tricked, kidnapped or forcibly abducted Korean girls to be ‘comfort women’.

朝鮮半島で朝鮮人女性を騙したり誘拐したりして強制連行したのはほとんど朝鮮人ですから

Statistical Yearbook of the Governor-General of Korea, from 1931

朝鮮総督府統計年報. 昭和 13年

Abduction and Kidnapping 略取及誘拐

Number of crimes where arrests were made 犯罪件数検挙

Number of completed or cleared cases, people in custody 検挙件数 検挙者

Crime of abduction and kidnapping 略取及び誘拐の罪

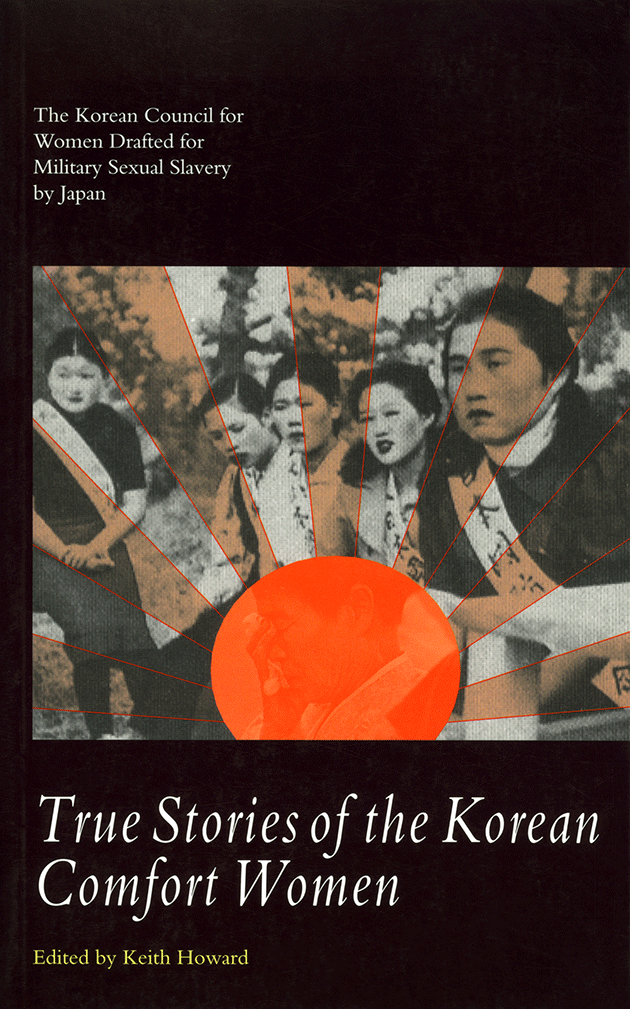

True Stories of the Korean Comfort Women

The Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan

Edited by Keith Howard

lecturer in Korean Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Testimonies compiled by the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan and Research Association on the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, and translated by Young Joo Lee.

Korean published 1993, English translation published 1995

page 23

After the War

Although the Japanese military exploited comfort women to such an extent, hardly any were taken back to Japan after the war. The treatment received by the women after Japan capitulated was in a way much more cruel than what they had been subjected to when they were initially drafted or when they later worked in the comfort stations. Many soldiers have stated that women were abandoned in their stations, were forced to take their own lives along with soldiers or were taken to caves or submarines and murdered.

Among those interviewed here, eight were able to leave their comfort stations before the war ended. Two ran away, one was sent home because she had a serious venereal disease, four received travel passes with the help of officers they had grown close to and one returned home with her proprietor. One went back to her first comfort station, and a total of 12 were able to return to Korea once the war ended. Only one of the 12 who returned to Korea initially left her comfort station with Japanese soldiers, while the other 11 say that soldiers simply suddenly stopped coming to the station. After the soldiers fled, abandoned women found their own way home or stayed in American refugee camps before they were shipped to Korea.

Those who had been comfort women suffered greatly back in Korea. They still suffered from diseases they had contracted while working in the comfort stations. They bore guilty consciences, simply because of the knowledge that they had been prostitutes. They suffered from the prejudice and discrimination of their relatives and friends. Many still had venereal disease or from time to time suffered its recurrence. The son of one became mentally disordered because his mother had venereal infection at the time of conception. Many women subsequently found they were barren, and many still suffer from ailments, from womb infections, high blood pressure, stomach trouble, heart trouble, nervous breakdowns, mental illness and so on. The psychological aftermath is far more serious than the physical suffering endured in the comfort stations. Apart from nervous breakdowns or mental disorders, the effects of which can be noticed externally, the minds of former comfort women are haunted by delusions of persecution, shame and inferiority. They tend to retain a distrust and hatred of men. They want to avoid contact with other human beings. Taken together, all of these make it difficult for the women to carry on any normal social life. The prejudice and discrimination heaped on them by society makes them feel particularly wretched. People around the women tend to despise them, guessing even if never told that they were sexually victimized while abroad. One woman we interviewed was thrown out of her house when her husband discovered the secrets of her past.

According to our research, women were most resentful of the fact that they were unable to lead ordinary married lives after their return. Six of the women we interviewed married, and five became second wives. But all marriages failed. Eight experienced some form of family life by moving in with men without marrying, but most of these relationships also ended in breakdown. Five women never married. Only two live with their own children; one stays with an adopted son, and one with a grandchild. The remaining 15 women now live on their own. All once tried to make a living on their own. They have, however, suffered from poor physical and mental health, hence work is difficult and all have consequently endured great financial difficulties. The women managed to survive an extremely harsh life on the battlefields of a foreign war, but the reality they have been forced to face since their return to Korea in peacetime has been nothing short of a continuation of their hardship, even though in a different form.

page 65

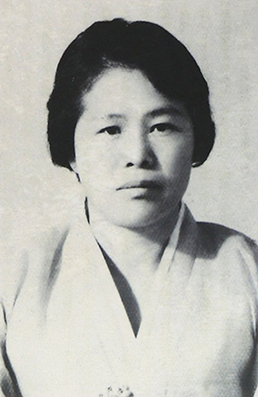

Oh Omok

Oh Omok was born in 1921, in Chŏngŭp, North Chŏlla province, the first child in a poor family of five children, two boys and three girls. In 1937, at 16 years of age, she was promised work in a textile factory in Japan by a Mr Kim from her home town. She left home with a friend. When they arrived in Manchuria, where Mr Kim handed them over to a Japanese man, they were taken to a Japanese unit and forced to become comfort women.

I was born into a poor family on 15 January 1921, in Chŏngŭp, North Chŏlla province. I was the eldest child, and I soon gained two brothers and two sisters. My father had been in poor health since I was very little and was now no longer able to work. My mother ran a small shop next to the police station where she sold vegetables. I couldn’t go to school, because we were too poor to pay the fees.

It was 1937, and I was 16. My parents had begun to try to find me a husband. One day a Mr Kim, from Chŏngŭp, visited us and said that he could get me a job in a textile factory in Japan. He also offered to find work for a friend of mine. He said that our job would be as weavers and added that we would be paid such and such a month. I forget the actual amount. After the visit he didn’t come back. We had almost forgotten about him when he suddenly reappeared and urged me to take the job which was on offer. I needed to earn money, so I went along with him, taking an old friend of mine called Okhŭi. She was two years younger than me. She used to visit me often and I had shown her how to embroider.

When I left home for the factory, my mother was expecting another child. It must have been winter, since I remember wearing padded clothes. Okhŭi and I arrived at Chŏngŭp station with Mr Kim, where there were three other girls waiting. We all got on board a train and travelled to Taejon, where Mr Kim bought us lunch. Then we boarded the train again and travelled for three or four days, all the way to Manchuria. Somewhere around Fengcheng we asked Mr Kim why he had brought us to China instead of Japan. He had, after all, promised to take us to Japan. He bluntly told us we must follow him. He handed us over to a Japanese man and promptly disappeared. From then on, with this new man, we continued our journey further north until we finally arrived right at the top-most tip of Manchuria, although I still don’t know what the place was called. It was very cold, and it was crowded with soldiers. There were mountains and rivers, and there were thousands of Chinese and Koreans milling around.

The five of us from Chŏngŭp were led to a village of tents on the outskirts of the place where the Japanese military units were based. There was a sea of tents surrounding the troops. Whenever new soldiers arrived, they would set up even more tents, because there was not enough room for them in the barracks that had already been built. There were already some 30 Korean women. We entered one tent. A soldier there cut my hair short and gave me a Japanese name, Masako.

There were women in every tent. They washed the soldiers’ clothes and they cooked for them in the kitchens. There was no fresh water supply in the whole village. The soldiers delivered meals to us. We had cooked rice mixed with barley, spinach or pickled radish, soup and occasional fish balls. We could often hear guns firing in the distance, and whenever there were air raids we were not allowed to light anything.

At first I delivered food for the soldiers and had to serve the rank and file, to have sex with them. There were Japanese as well as Koreans among the managers who instructed us where to go each day. On receiving orders we were called to the appropriate unit and served five or six men a day. At times we would serve up to ten. We served the soldiers in very small rooms with floors covered with Japanese-style mats, tatami. There were many rooms. We lived in the tents and were summoned to the barracks whenever required. We were given blankets by the army, and when it was very cold we used hot water tins. The only toilets were outside the tents, as were the bathrooms, and such facilities were separated for men and women. When the soldiers were away on an expedition it was nice and quiet, but once they returned we had to serve many of them. Then they would come to our rooms in a continuous stream. I wept a lot in the early days. Some soldiers tried to comfort me saying ‘kawaisōni or ‘naitara ikanyo’ which meant something like ‘you poor thing’ and ‘don’t cry’. Some of the soldiers would hit me because I didn’t understand their language. If we displeased them in the slightest way they shouted at us and beat us: ‘bakayarō’ or ‘kisamayaro’, ‘you idiot’ and ‘you bastard’. I realized that I must do whatever they wanted of me if I wished to survive. There was no payment given to any of us for cooking or washing clothes, but we were paid whenever we slept with soldiers. The bills they handed over were blue and red. There were some women who set up home with soldiers in tents, and a few of them even had children.

The soldiers used condoms. We had to have a medical examination for venereal infections once a week. Those infected took medicine and were injected with ‘No. 606’. Sometime later, I became quite close to a Lieutenant Morimoto, who arranged for Okhŭi and me to receive only high-ranking officers. Once we began to exclusively serve lieutenants and second lieutenants, our lives became much easier. When I was 21, in 1941, I had to have my appendix out, but the operation didn’t go well and I was readmitted to hospital for a second, follow-up operation. I remember Morimoto coming to see me. The hospital chief was Japanese, and the patients were mostly soldiers and Chinese women. The fee for the operations must have been paid by the army. Afterwards I was able to take a break from serving soldiers. During my convalescence I did various chores: I cooked, filled bathtubs, heated the bath water and so forth.

We moved along with the army. I cannot remember what it was called. We moved south in China. When we were stationed in Nanjing we were sometimes able to see films with the soldiers. We mainly watched war films. The comfort station there was housed in a Chinese building. It was not so cold there. We wore Western style dresses and occasionally were able to buy Chinese clothes. Fukiko, Masako and Fumiko were among the five of us who went there together, but all the others died except Fukiko. One of them died of serious syphilis. There was a sign in front of the house, but I don’t remember what it said. In Nanjing we had to serve many soldiers, just as usual. Whenever they came into the building, we had to say ‘irassyai’. This meant ‘welcome’. There was a bed and a mirror in each room.

I cannot remember where it was, but we had to do training under the supervision of the soldiers. Each of us wore a sash on our shoulder with Women’s National Defence Society written on it. We wore caps and baggy black trousers. There were Japanese women and civilians who trained with us, and after each training session we returned to our station.

It was while we were there that we were liberated. There was a Korean man from Kwangju who lived in Nanjing with his wife and family, trying to run a business. I used to call him my big brother, and we got on very well. After Korea was liberated Okhŭi and I returned with this man and his family. On our way back, many people with us died in a train accident, but we were delivered safely. I wept and wept as we travelled back to our homeland, and ‘big brother’ tried to console me. He, with his wife and family, went their own way half-way through the journey, and Okhŭi and I were left alone. We noticed lots and lots of Russian troops on the way, and there was a rumour going around that they would take away young women, just as the Japanese had done before them. So we smudged our faces with soot, and continued our journey looking like tramps. In Shinŭiju we stayed overnight in a Korean guest-house. Russian soldiers rushed in during the night, apparently looking for young women, so we hid in a wardrobe. They must have gone, but we stayed confined in there all night.

We got on a ship from Shinŭiju to Inch’ŏn, and then took a train to Chŏngŭp. I was wearing flat yellow shoes I had bought in China, and a short-sleeved blouse. We bid goodbye to each other at the station, and I took a rickshaw home. My brother, Kŭmsu, who was in primary school at the time, still remembers me arriving on the rickshaw! My other brother was cutting firewood, and when he heard I was home he dropped everything and ran back to the house. My parents said that they had given me up for dead. My mother was so shocked to see me after such a long time that she fainted. After nine years in China, I found it hard at first to understand my own language. I had a small bamboo bag from Japan with me in which I carried some photographs and Chinese shoes. But in order to forget that part of my life, I burnt these souvenirs later on.

For a few years I stayed with my parents. I lied to them about my life in China, saying I had worked as a domestic help. I was still young, and felt that I could do anything with my life. My parents tried to find me a husband, but I said I wanted to live alone. They finally found me a room, and my mother bought me a pair of beautiful shoes, even though she was still very poor. She also got me many herbal cordials to build up my strength. After 1945, my parents were running a small restaurant in a boarding house for policemen. My father died of illness in 1951, and at the age of 33 I married a farmer whose wife had also died. I had been told that he had two children from his first wife, but after the marriage I found out that he had five! Marrying him meant I had to move to Seoul, and I lived with him for a number of years, looking after those five children. I found it hard to bring up someone else’s kids, and I soon discovered that I wasn’t able to have any of my own. When I was 48 I left him, taking with me the baby of my housemaid. I adopted that baby girl and lived back in Chŏngŭp for three years, without letting anyone know my exact whereabouts, not even my own brothers. It was hard to bring up a child on my own. I lived on cooked barley, working at silkworm farms on a daily wage of 2500 wŏn. I could not afford to send my adopted daughter to school until she was nine but, seeing me struggling to survive, she left school during her sixth grade and began to work in a factory that made bamboo umbrellas. I didn’t tell her that she had been adopted, just that her father had died. She is 21 now, married to a stonemason. They live in Asan county, South Ch’ungch’ŏng province. They have a three-year-old son and are expecting a second child soon. So that they were able to register the birth of their child, I had to register the birth of my adopted daughter as my own daughter. I had been scared to do this earlier.

Okhŭi used to say that, since we couldn’t have children or be married, we should live on our own. She used to visit me often and we would cry together, talking about our miserable past. She, too, lived on government aid until she died of cancer last year. I have been on the list to receive state benefit for the past three years. In the autumn I work, picking red peppers from their stalks. If I work from dawn until dusk, I get paid something between 3000 and 5000 wŏn ($4 to $6) a day. I have very little income, so I don’t pay any tax, but I have to pay 300,000 wŏn ($375) every ten months for my room. Last year I wasn’t able to pay it. My only wish is to be able to live without worrying about rent. And I still feel resentful that I haven’t been able to have children because of what happened almost 50 years ago.

http://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20160610/p2a/00m/0na/015000c

U.S. military documents featuring Korean POW testimony discovered at U.S. National Archives

Documents containing testimony on Japanese rule and wartime mobilization from Korean civilians who had been with the Imperial Japanese Army prior to their capture as prisoners of war (POWs) by U.S. Forces toward the end of the Pacific War have been discovered at the U.S. National Archives, and are expected to reignite debate regarding forced laborers and so-called “comfort women.”

The Asian Women’s Fund – established by the Japanese government in 1995 and run through 2007 in an effort to resolve the “comfort women” issue – set up a committee on gathering historical documents, which in 1997 found the responses given by the POWs during investigative research in the U.S. The documents subsequently went missing, but were located again this year when Waseda University professor Toyomi Asano, who specializes in Japanese political history, together with the Mainichi Shimbun, found in March the documents containing the U.S. military’s questions and other related information.

After the U.S. military interrogated around 100 Korean prisoners, they chose three whom they transported to an interrogation center at Camp Tracy in California for further questioning. The documents indicate that the three prisoners were asked 30 additional questions on April 11, 1945.

Both the names of the interrogators and the prisoners are indicated on the documents, and the answers given by the three prisoners are compiled as single answers. The preamble to the prisoners’ answers states, “The general anti-Japanese feeling of these Koreans is the same as almost all of some 100 prisoners of war questioned by the interrogator,” adding, “It is probably that some Koreans are opportunists but these three appear to be very sincere in their statements which may be considered reliable.”

As for questioning regarding so-called “comfort women,” the three prisoners were asked, “Do Koreans generally know about the recruitment of Korean girls by the Japanese Army to serve as prostitutes? What is the attitude of the average Korean toward this program? Does the P/W know of any disturbances or friction which has grown out of this program?”

The three prisoners are recorded as having responded, “All Korean prostitutes that PoW have seen in the Pacific were volunteers or had been sold by their parents into prostitution. This is proper in the Korean way of thinking but direct conscription of women by the Japanese would be an outrage that the old and young alike would not tolerate. Men would rise up in rage, killing Japanese no matter what consequence they might suffer.”

In response to a question about the procedures through which Korean laborers were sent to Japan Proper, and whether they arrived in Japan Proper voluntarily or were conscripted, the three prisoners said that “Korean men (had) been conscripted to work in Japan since 1942,” and that they knew people “working in coal and iron mines, and building airfields.” They also said that “they were always required to do the worst type of work such as was found in the deepest and hottest part of a mine.” Meanwhile, they said they were allowed to correspond with family, but that “all mail was censored.”

Much of U.S. military interrogations of POWs were of Japanese nationals, and testimonies given by Koreans are rare. Among interrogations of “comfort women,” there is a report compiled through questioning of Korean “comfort women” who were captured in Burma (present-day Myanmar) as the result of U.S. military psychological operations (PSYOPs). The most recently discovered documents are an extension of that report, and are believed to have been an effort by the U.S. military to feel out the level of Koreans’ defiance toward Japanese colonial rule with an eye to seizing the Korean Peninsula.

Korean POW testimony documents discovered at U.S. National Archives (PDF file) :

http://cdn.mainichi.jp/vol1/2016/06/10/20160610p2a00m0na015000q/0.pdf

http://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20160610/p2a/00m/0na/018000c

Korean testimony docs highlight ethnic, gender discrimination under Japanese colonial rule

Testimonies given by Korean civilians to U.S. military officials on their treatment under Japanese colonial rule, which were recently re-discovered at the U.S. National Archives, highlight the ethnic and gender discrimination that governed Japanese policy at the time. …

The interrogations are valuable also for having been conducted at a time when the prisoners did not know where the war was headed, were under little pressure, and had a fair amount of freedom. The testimonies represent the sentiments of the lowest ranks of Korean society at the time. …

They also said that had there been explicitly forced conscription of so-called “comfort women,” the Korean people would be infuriated. …

According to testimonies from former “comfort women,” we know that there were many cases of women being defrauded into becoming “comfort women” after they were told they’d be given lucrative work. The sexism ingrained in society and the poverty faced by the Korean peninsula under Japanese colonial rule made it particularly easy to commit such employment fraud. …

http://scholarsinenglish.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-comfort-women-by-chunghee-sarah-soh.html

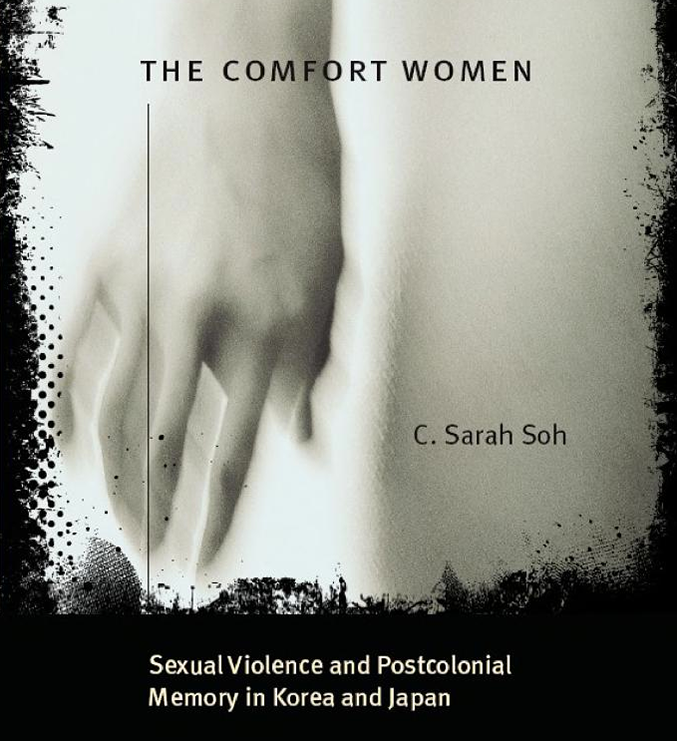

“The Comfort Women” by Professor C. Sarah Soh

from the back cover:

In an era marked by atrocities perpetrated on a grand scale, the tragedy of the so-called comfort women – mostly Korean women forced into prostitution by the Japanese army – endures as one of the darkest events of World War II. These women have usually been labeled victims of a war crime, a simplistic view that makes it easy to pin blame on the policies of imperial Japan and therefore easier to consign the episode to a war-torn past. In this revelatory study, C. Sarah Soh provocatively disputes this master narrative.

Soh reveals that the forces of Japanese colonialism and Korean patriarchy together shaped the fate of Korean comfort women – a double bind made strikingly apparent in the cases of women cast into sexual slavery after fleeing abuse at home. Other victims were press-ganged into prostitution, sometimes with the help of Korean procurers. Drawing on historical research and interviews with survivors, Soh tells the stories of these women from girlhood through their subjugation and beyond to their efforts to overcome the traumas of their past. Finally, Soh examines the array of factors – from South Korean nationalist politics politics to the aims of the international women’s human rights movement – that have contributed to the incomplete view of the tragedy that still dominates today.

Professor Chunghee Sarah Soh was born in South Korea and graduated from Sogang University there. She then moved to the United States and received her Ph.D. in anthropology from University of Hawaii. She is a professor of anthropology at San Francisco State University.

In this book, Professor Soh criticizes the South Korean activist group “Korean Council” (also known as Chong Dae Hyup 정대협 挺対協 in Korean) for spreading North Korean propaganda and using the comfort women issue to block reconciliation between Japan and South Korea. She insists that Korean society must repudiate victimization, admit its complicity and accept that the system was not criminal. She also argues that the case of a small number of Dutch and Filipino women who were coerced by lower ranked Japanese soldiers in the battlefields was an anomaly, and that most women (Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese) were recruited and employed by prostitution brokers.

The following is an excerpt from her book “The Comfort Women.” (Pages 10-11)

By 1920 some Korean women had become “overseas prostitutes.” Those who worked at a restaurant in Sapporo, Japan, became what Yun Chǒng-ok calls “industrial comfort women,” serving Korean men who worked there.43 When the adult entertainment business in Korea suffered as a result of the Great Depression of the 1920s, female workers and business owners migrated to China. By the late 1920s the capital of colonial Korea, Kyǒngsǒng, was home to four pleasure quarters, which employed a total of 4,295 prostitutes.44 By the mid-1930s 45 percent of Koreans had become infected with syphilis, compared to 15 percent of the French.45 Beginning in the early 1930s many Korean women were sold overseas to labor as prostitutes. Dong-A Ilbo, one of Korea’s major daily newspapers dating from the colonial days, reported on December 2, 1932, that about a hundred women a month were sold for 40 to 50 won to brothels in Osaka, Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and Taiwan; this report, in hindsight, seems to predict the large-scale mobilization of Korean women to serve the troops through the 193os up to 1945. In fact, the survivors’ testimonials amply illustrate that during the war Korean men and women actively collaborated in the recruitment of young compatriots to service the Japanese military and also ran comfort stations. For young, uneducated women from impoverished families in colonial Korea, to be a victim of trafficking became “an ordinary misfortune” in the 193os.46 Amid widespread complicity and indifference to young women’s plight, the adult entertainment business in Korea began to recover after the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, and it flourished until early 1940.

When the war effort intensified in the early 1940s, however, many adult entertainment establishments had to close down, and by 1943 it was practically impossible to run such a business. This encouraged some brothel owners to seek their fortune abroad, including in Taiwan and occupied territories in the Southeast Asia. As Song Youn-ok noted, had there not been a “widespread network of traffic in women used in the state-managed prostitution system, the mobilization of Korean comfort women would have been a very different process”47 Under grinding poverty, working-class families in colonial Korea sold unmarried daughters for 400-500 wǒn for a contractual period of four to seven years. The parents received 60-70 percent of the money after various expenses involved in the transaction had been deducted, such as the mediator’s fee, clothing, document preparation, transport, and pocket money.48 Kim Sun-ok, who labored at a comfort station in Manchuria for four years, recalled:

“I had no childhood. I was sold four times from the age of seven. As soon as I returned to my home in P’yǒngyang from Sinŭiju after paying off my debt of 500 wǒn, I recall that procurers began showing up at my house, coaxing my parents. I declared to my parents that I was not going anywhere and begged them not to sell me again. However, I could sense that my parents were being influenced, and it appeared that I would be sold to Manchuria. I contemplated a variety of methods of killing myself. But my love of life and hope for a change in the future prevented me from committing suicide. My father entreated me and said: “It’s not because of cruelty that your father wants to sell you. In comparison to your siblings, you have the attractive looks and the experiences of living away from home. It’s your misfortune to have someone like me as a father. Go this one time. They promise to send you to a factory, which should be a good thing.”

Within a fortnight after my return home from Sinŭiju, I was sold for a fourth time and sent off to a military comfort station in Manchuria in 1941.49

In this excerpt it says, “By 1920 some Korean women had become overseas prostitutes. Those who worked at a restaurant in Sapporo became industrial comfort women, serving Korean men who worked there.” “Beginning in the early 1930’s many Korean women were sold overseas to labor as prostitutes. Dong-A Ilbo, one of Korea’s major daily newspapers dating from the colonial days, reported on December 2, 1932, that about a hundred women a month were sold for 40 to 50 won to brothels in Osaka, Hokkaido, Sakhalin and Taiwan; this report, in hindsight, seems to predict the large-scale mobilization of Korean women to serve the troops through the 1930’s up to 1945. In fact, survivors’ testimonials amply illustrate that during the war Korean men and women actively collaborated in the recruitment of young compatriots to serve the Japanese military and also ran comfort stations.” “Under grinding poverty, working class families in colonial Korea sold unmarried daughters for 400 to 500 won for a contractual period of four to seven years. The parents received 60 to 70 percent of the money after various expenses involved in the transaction had been deducted.”

In an interview with Professor Chunghee Sarah Soh of San Francisco State University, a former Korean comfort woman Kim Sun-ok said that she was sold by her parents four times.

Yet she testified in front of UN interrogator Radhika Coomaraswamy that she was abducted by Japanese military.

In an interview with Professor Park Yuha of Sejong University in South Korea, a former Korean comfort woman Bae Chun-hee said that she hated her father who sold her.

Yet she testified in front of UN interrogator Radhika Coomaraswamy that she was abducted by the Japanese military.

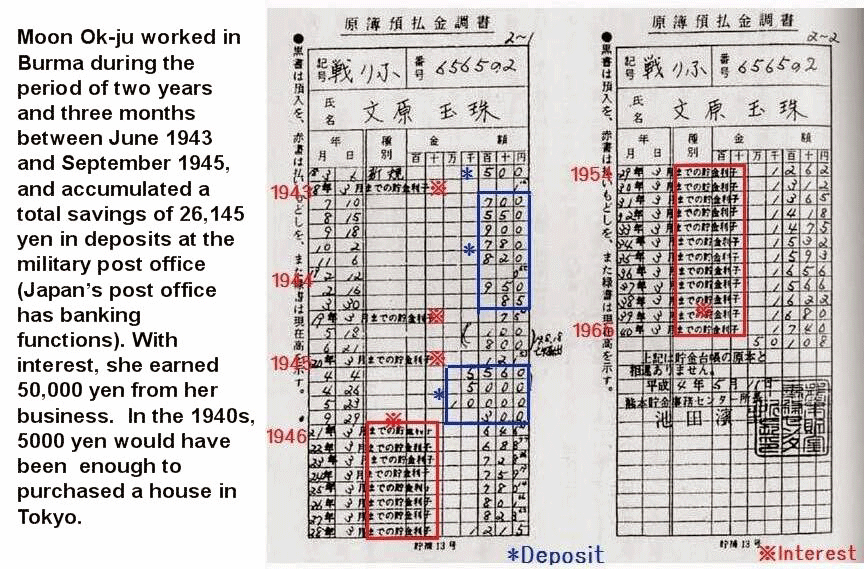

A former Korean comfort woman Mun Oku-chu said in her memoir:

“I was recruited by a Korean prostitution broker. I saved a considerable amount of money from tips, so I opened a saving account. I could not believe that I could have so much money in my saving account. One of my friends collected many jewels, so I went and bought a diamond. I often went to see Japanese movies and Kabuki plays in which players came from the mainland Japan. I became a popular woman in Rangoon. There were a lot more officers in Rangoon than near the frontlines, so I was invited to many parties. I sang songs at parties and received lots of tips. I put on a pair of high heels, a green coat and carried an alligator leather handbag. I swaggered about in a fashionable dress. No one in town could guess that I was a comfort woman. I felt very happy and proud. I received permission to return home, but I didn’t want to go back to Korea. I wanted to stay in Rangoon.”

According to Professor Chunghee Sarah Soh’s book, Mun Oku-chu continued to work as a prostitute in Korea after the war.

Yet she testified in front of UN interrogator Radhika Coomaraswamy that she was abducted by Japanese military.

See below for extracts from the book Mun Oku-chu wrote.

In an interview with Korean newspaper The Hankyoreh (the article was published on May 15, 1991) a former Korean comfort woman Kim Hak-sun said that she was sold by her mother.

In an interview with Professor Chunghee Sarah Soh of San Francisco State University, Kim Hak-sun said that her mother sent her to train as a Geisha in Pyongyang before she sold her.

Yet she testified in front of UN interrogator Radhika Coomaraswamy that she was abducted by Japanese military.

In an interview with Professor Ahn Byong Jik of Seoul University, a former Korean comfort woman Kim Gun-ja said that she was sold by her foster father.

Yet she testified in front of UN interrogator Radhika Coomaraswamy that she was abducted by Japanese military.

Kim Gun-ja also testified in front of United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs in 2007 and said she was abducted by Japanese military.

In an interview with Professor Ahn Byong Jik of Seoul University, a former Korean comfort woman Lee Yong-soo said that she and her friend Kim Pun-sun were recruited by a Korean prostitution broker.

In an interview with Professor Chunghee Sarah Soh of San Francisco State University, Lee Yong-soo said, “At the time I was shabbily dressed and wretched. On the day I left home with my friend Pun-sun without telling my mother, I was wearing a black skirt, a cotton shirt and wooden clogs on my feet. You don’t know how pleased I was when I received a red dress and a pair of leather shoes from a Korean recruiter.”

Yet she testified in front of UN interrogator Radhika Coomaraswamy that she was abducted by Japanese military.

Lee Yong-soo also testified in front of United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs in 2007. She was told that she had five minutes to speak. She ignored the instruction and went on for over one hour putting on a performance of crying and screaming. Her false testimony resulted in the passage of United States House of Representatives House Resolution 121.

In an interview with Professor Ahn Byong Jik of Seoul University, a former Korean comfort woman Kim Ok-sil said that she was sold by her father.

In an interview with Professor Chunghee Sarah Soh of San Francisco State University, Kim Ok-sil said that her father sent her to train as a Geisha in Pyongyang before he sold her.

Yet she testified in front of UN interrogator Radhika Coomaraswamy that she was abducted by Japanese military.

In an interview with Professor Ahn Byong Jik of Seoul University, a former Korean comfort woman Kil Won-ok said that she was sold by her parents.

In an interview with Professor Chunghee Sarah Soh of San Francisco State University, Kil Won-ok said that her parents sent her to train as a Geisha in Pyongyang before they sold her.

Yet she testified in front of UN interrogator Radhika Coomaraswamy that she was abducted by Japanese military.

Several people had witnessed the scenes in which Chong Dae Hyup (정대협 挺対協 anti-Japan lobby) coached women to say “I was abducted by Japanese military.”

Professor Ahn Byong Jik of Seoul University who interviewed former Korean comfort women says, “When I first interviewed them, none of them had anything bad to say about Japanese military. In fact they all reminisced the good times they had with Japanese soldiers. But after Chong Dae Hyup confined them, their testimonies had completely changed.”

See Footnotes

1. C. Sarah Soh — Study across cultures (1999 interview)

2. C. Sarah Soh — Human Dignity and Sexual Culture: A Reflection on the ‘Comfort Women’ Issues

Japanese soldiers did abduct dozens of Dutch and Filipino women in the battlefields of Indonesia and the Philippines. (Those soldiers were court-martialed, and some of them were executed.) But Korean women were not abducted by Japanese military because the Korean Peninsula was not the battlefield and therefore Japanese military was NOT in Korea. (Korean prostitution brokers recruited Korean women in Korea and operated comfort stations in the battlefields) Japan apologized and compensated, and Netherlands, Indonesia, the Philippines and Taiwan had all accepted Japan’s apology and reconciled with Japan. So there are no comfort women issues between those nations and Japan. The comfort women issue remains only with South Korea because Chong Dae Hyup refuses to accept Japan’s apology and continues to spread the false claim of “200,000 young girls including Koreans were abducted by Japanese military” throughout the world.

http://scholarsinenglish.blogspot.com/2014/10/summary-of-professor-park-yuhas-book.html

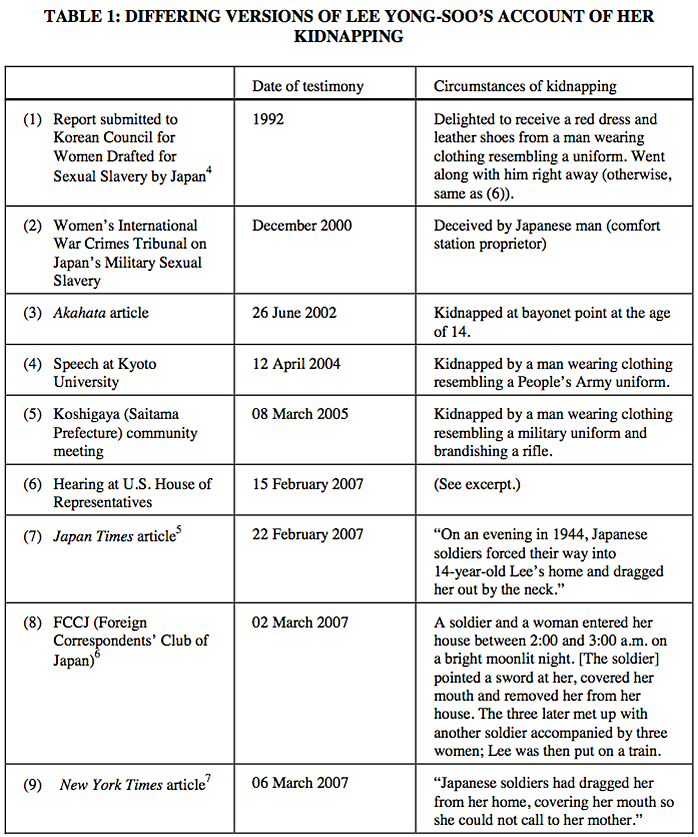

“Comfort Women of the Empire” the battle over colonial rule and memory

by Park Yu-ha (박유하, 朴裕河)

The following is a summary English translation of a book titled “Comfort Women of the Empire” by Professor Park Yuha of Sejong University in South Korea.

The original book in Japanese:

帝国の慰安婦 植民地支配と記憶の闘い

by 朴 裕河 (336 pages)

November 7, 2014 ISBN-13: 978-4022511737

Park was born on March 25, 1957. She graduated from Keio University in 1981. She earned her M.A. from Waseda University in 1989 and PhD. in 1993.

Her research focuses on Japan-Korea relations. Her recent book Comfort Women of the Empire criticizes the narrow-minded Korean interpretation of Comfort Women which only emphasizes “sex slaves.”

Preface

I first confronted the comfort women issue in 1991. It was near the end my study in Japan. As a volunteer I was translating former Korean comfort women’s testimonies for NHK. When I returned to South Korea, Kim Young-sam was the president, and Korean nationalism was on the rise. The anti-Japan lobby “Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan” or “Chong Dae Hyup” (정대협 挺対協) in Korean was really gaining momentum. Its leader said publicly it was determined to discredit Japan for the next 200 years. Its propaganda turned me off, so I stayed away from this issue for years. I regained my interest in this issue in the early 2000’s when I heard that Chong Dae Hyup was confining surviving women in a nursing home called “House of Nanumu.” The only time these women were allowed to talk to outsiders was when Chong Dae Hyup needed them to testify for UN interrogators or U.S. politicians. But for some reason I was allowed to talk to them one day in 2003. I could sense that women were not happy being confined in this place. One of the women (Bae Chun-hee) told me she reminisced the romance she had with a Japanese soldier and the sorrow when he died in combat. She said she hated her father who sold her. She also told me that women there didn’t appreciate being coached by Chong Dae Hyup to give false testimonies but had to obey Chong Dae Hyup’s order. When Japan offered compensation through Asian Women’s Fund in 1995, about 60 former Korean comfort women defied Chong Dae Hyup’s order and accepted compensation. Those 60 women were vilified as traitors. Their names and addresses were published in newspapers as prostitutes by Chong Dae Hyup, and they had to live the rest of their lives in disgrace. So the surviving women were terrified of Chong Dae Hyup and wouldn’t dare to defy again.

1. The origin of comfort women

With Japan’s victory in Sino-Japanese war (1894 – 1895) the Korean Peninsula was no longer under the control of Qing Dynasty China. As Japanese military personnels and male workers began to spend time in Korea, women (mostly from Nagasaki and Kumamoto) followed to comfort them. Most of these women were from poor families.

2. Korean comfort women

At first comfort women were all Japanese. But after Korea became part of Japan in 1910, ethnic Korean women (Japanese citizens) also became comfort women. By the 1920’s Japanese women along with Korean women traveled abroad to comfort Japanese men and ethnic Korean men there. These Korean women were the predecessors of who later became known as Korean comfort women.

3. Comfort women and female troops

Although women were working as prostitutes, some of them had accumulated enough savings to lend money and rent places for secret meetings to men who were fighting for the nation. That is why they were also called female troops(娘子軍)and they took certain pride in their contribution.

4. Comfort stations

One shouldn’t think comfort women system was created suddenly by Japanese military in the 1930’s. At first Japanese military licensed existing prostitution houses in Manchuria as comfort stations. As Japan advanced into China and Southeast Asia, more comfort stations were needed. So Japanese military commissioned prostitution brokers to recruit more women and create more comfort stations. Japanese brokers recruited Japanese women in Japan. They owned and operated comfort stations employing Japanese women. Korean brokers recruited Korean women in Korea. They owned and operated comfort stations employing Korean women. (See footnote *3, *4)

5. Two types of comfort women

There were two types of comfort women. (1) Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese women (all Japanese citizens) They were not coerced by Japanese military. (2) Local women in the battlefields (Dutch women in Indonesia, Filipino women in the Philippines, etc.) Dozens of them were coerced by lower ranked Japanese soldiers. These two types should have been treated differently. But when the comfort women became an issue in the early 1990’s, all women who provided sex to Japanese military were treated uniformly, and that created a big confusion.

6. The Myth “Korean comfort women were coerced by Japanese military”

The Korean woman who first claimed this in the early 1990’s belonged to Chongsindae during the war. Chongsindae (also called Teishintai in Japanese) was a group of teenage girls conscripted by Japanese military. They worked in factories to manufacture military equipments and uniforms. Since she was conscripted, she thought comfort women were also conscripted. It wasn’t that she fabricated the story. It was an innocent mistake on her part. When I examined initial testimonies of former Korean comfort women, none of them claimed she was coercively taken away by Japanese military. It should be noted, however, that Korean brokers sometimes lied about description of work. (They sometimes hinted women would be working as nurses and so on) So although Korean comfort women were not coerced by Japanese military (Japanese military was NOT in Korea), some of them were recruited on false pretenses by Korean brokers. Other Korean women were in the world’s oldest profession, and they did volunteer to earn good money.

7. The Myth “200,000 young girls were coerced by Japanese military”

Two hundred thousand was the number of factory workers conscripted. About 150,000 of them were Japanese and 50,000 were Koreans. Many of them were teenage girls. Common misunderstanding in the West of “200,000 young girls were coerced by Japanese military” arose because Asahi Shimbun mistook factory workers for comfort women in August 11th, 1991 article, which inflated the number. The estimates of comfort women numbers vary from 20,000 to 70,000 depending on the historians. Most comfort women were Japanese, Koreans and Taiwanese, and they were recruited by brokers, not by Japanese military. In the battlefields of Indonesia and the Philippines, dozens of Dutch and Filipino women were abducted by lower ranked Japanese soldiers and were taken to comfort station operators. (Those soldiers and operators were court-martialed, and some of them executed) Most comfort women were not teenage girls but were in their 20’s and 30’s. So the correct statement should instead be “Between 20,000 and 70,000 worked as comfort women, of which dozens were abducted by Japanese soldiers.”

8. Japanese military and Korean comfort women

Korean comfort women worked in kimono using Japanese names. Since they were working for Japan’s victory, lower ranked soldiers committing violence to women were punished by higher ranked officers. Korean comfort station owners exploiting Korean women were also punished. Korean women typically made about 750 yen a month including tips. (A house in Korea cost 1000 yen at the time) Women attended sports events, picnics and social dinners with both officers and men. They were also allowed to go shopping in towns. Romances between Korean comfort women and Japanese soldiers were common, and there were numerous instances of proposals of marriage and in certain cases marriages actually took place.

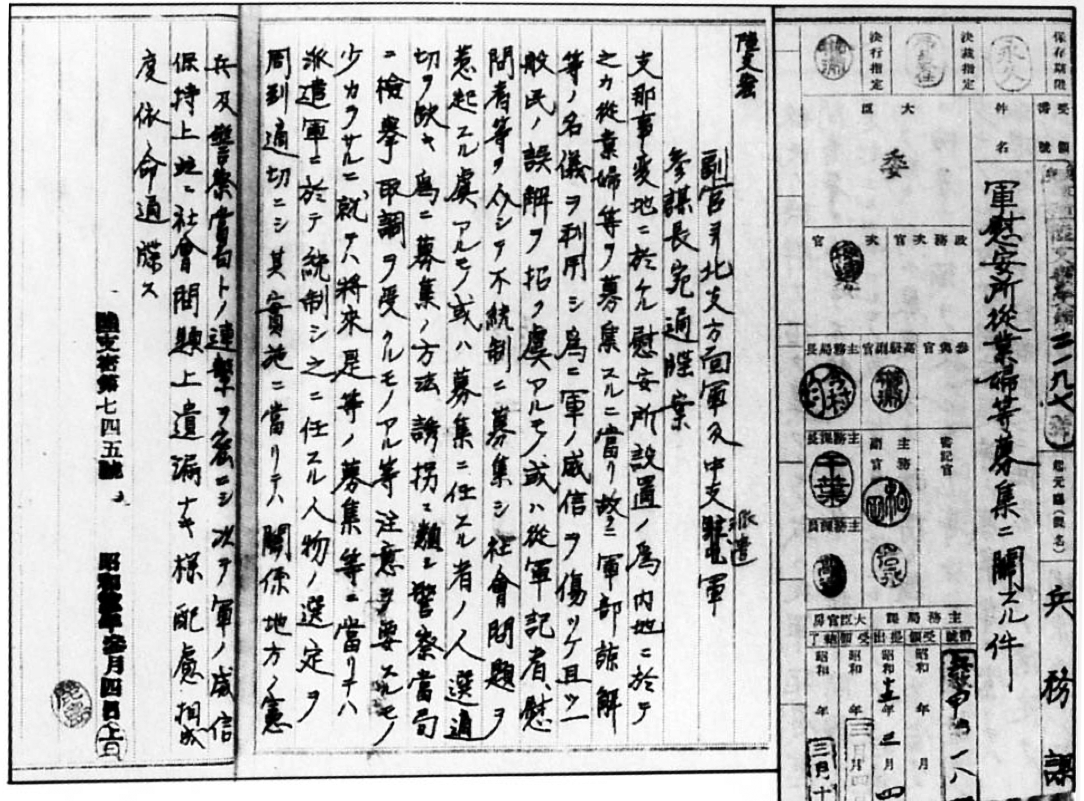

9. Korean prostitution brokers

There is no evidence to support that Japanese military permitted Korean prostitution brokers to lie or use violence when recruiting Korean women or operating comfort stations. In fact there are documents which indicate that Japanese military sent orders to police in Korea to crack down on Korean brokers who engage in illegal recruiting. (See footnote *6, *7) Any coercion, violence or confinement was exercised by Korean brokers against the orders. So if one wants to use the term “sex slaves” to describe former Korean comfort women, they were sex slaves of Korean brokers. They were not sex slaves of Japanese military. Japanese military personnels visited comfort stations only as customers. A diary written by a Korean comfort station manager was discovered in 2012 (See footnote *3), and it makes it clear that Korean brokers not only recruited women in the Korean Peninsula but also owned and operated comfort stations employing Korean women. And Korean women were treated badly by Korean brokers according to the memoir written by a former Korean comfort woman. Japanese and Taiwanese women worked at comfort stations owned and operated by Japanese brokers and were treated much better. That is why we hear little or no complaint from former Japanese and Taiwanese comfort women. Again, the common perception in the West that Japanese military operated comfort stations is incorrect.

10. Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty of 1910

Some argue that since not all Koreans agreed to this treaty, it is not legally binding. However, even if some Koreans did not like this treaty, official Korean representatives did sign the treaty, and treaty documents do exist. So it is not reasonable to say this treaty is not legally binding.

11. Japan-South Korea Treaty of 1965

1965 Japan-South Korea Treaty was concluded to decide how to distribute assets. Japanese government asked South Korean government during treaty negotiation to identify and separate individual claims from the treaty because Japanese government wanted to make sure victims received compensation by delivering compensation directly to them. South Korean government declined, accepted the entire sum of 800 million dollars in place of its citizens and spent all of it on infrastructure and so on. Therefore it is not reasonable for South Korean government to keep asking for additional compensation from Japan.

(Note: Korean victims recently sued the South Korean government claiming that 300 million of the 800 million dollars were meant for them.)

12. Kono Statement in 1993

Kono Statement acknowledged that some Korean comfort women were recruited on false pretenses by Korean prostitution brokers. But it did not acknowledge that Japanese military coerced them. Therefore, there is no need to revise Kono Statement. Some might argue that if some Korean women were recruited on false pretenses by Korean brokers, why was it necessary for Japanese government to apologize via Kono Statement. Well, no matter who recruited Korean women, they still suffered. So Japan’s apology was a good gesture.

13. Asian Women’s Fund

Asian Women’s Fund was established by Japanese government in 1995. (Compensation came with a personal letter of apology from Prime Minister of Japan) As for Korean women, although they were not coerced by Japanese military and all individual claims were settled in 1965 Japan-South Korea Treaty, Japanese government still offered additional compensation to Korean women through Asian Women’s Fund as a good gesture. Ironically every nation involved except South Korea accepted compensation through Asian Women’s Fund and reconciled with Japan. (Note: South Korean government and Korean women wanted to accept Asian Women’s Fund as well, but the anti-Japan lobby ‘Chong Dae Hyup’ threatened Korean women not to accept Japan’s apology and compensation so that it could continue its anti-Japanese propaganda campaign. So most Korean women could not accept Japan’s apology and compensation.)

14. Why has it been so difficult to resolve this issue only with South Korea?

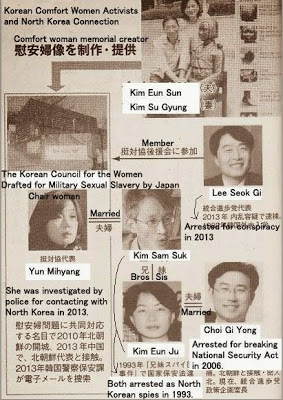

The anti-Japan lobby Chong Dae Hyup (정대협 挺対協) opposed Asian Women’s Fund claiming it did not go through a legislation vote in the House. But considering all individual claims were settled in 1965 Japan-South Korea Treaty, a cabinet member decision was the best Japanese government could do. (A legislation vote in the House would have breached 1965 treaty) Chong Dae Hyup has had a very close relationship with North Korea. (The leader’s husband was arrested as a North Korean spy. See footnote *9) In my opinion, the real reason why Chong Dae Hyup opposed Asian Women’s Fund was because it wanted to use the comfort women issue to block reconciliation between Japan and South Korea. Japan-South Korea discord is precisely what North Korea wants. The dynamics of South Korean politics is very difficult for foreigners to grasp. South Korean politics is split 50/50 between right and left. The right is pro-U.S., anti-North Korea and anti-Japan. The left is anti-U.S., pro-North Korea and anti-Japan. Chong Dae Hyup is a radical element of South Korean left. So South Korean rightists do not get along with Chong Dae Hyup. But anti-Japanese sentiment in South Korea is shared by right and left due to decades of brainwashing by successive governments. Consequently, South Korean rightists (especially media and politicians) do not interfere with Chong Dae Hyup’s propaganda campaign.

15. World’s view

Instead of reconciling with Japan by accepting Japan’s apology and compensation, Chong Dae Hyup (≒ North Korea) and its U.S. affiliate KACE have appealed to the world by dragging former Korean comfort women (now in their 80’s and 90’s) around the world as exhibitions. UN reports such as Coomaraswamy Report and U.S. House Resolution 121 were issued based solely on materials provided by the Korean lobby. (False testimonies of women who were coached by Chong Dae Hyup. Reference) Most Western media and scholars fell for Chong Dae Hyup’s (North Korean) propaganda and believe “200,000 young girls including Koreans were coercively taken away by Japanese military.” Obviously this world-view is not based on the facts.

Lower ranked Japanese soldiers did coerce dozens of Dutch and Filipino women in the battlefields of Indonesia and the Philippines. But not 200,000! And Korean women were not coerced by Japanese military because the Korean Peninsula was not the battlefield and therefore Japanese military was NOT in Korea. (Korean brokers recruited Korean women in Korea and operated comfort stations employing them) Japan apologized and compensated, and Netherlands, Indonesia, the Philippines and Taiwan had all accepted Japan’s apology and reconciled with Japan. So there are no comfort women issues between those nations and Japan. The comfort women issue remains only with South Korea because Chong Dae Hyup refuses to accept Japan’s apology and continues to spread the false claim of “200,000 young girls including Koreans were coerced by Japanese military” throughout the world. Chong Dae Hyup is a very powerful special interest group in South Korea, and Korean politicians are scared to death to defy it. But South Korean government must somehow distance itself from Chong Dae Hyup if this issue is to be resolved. After all, Chong Dae Hyup has no interest in the welfare of former Korean comfort women. Its goal is to discredit Japan and to block reconciliation between Japan and South Korea.

16. Empires and comfort women

Just like the empires were created by European powers and Japan in the past, the United States has military bases all over the world. And wherever U.S. military bases are located, there are women who provide sex to U.S. military personnels. There is no doubt that U.S. military interventions in Vietnam, Iraq and so on had caused suffering to local people especially to women. It is rather ironic that the United States keeps coming up with resolutions to criticize Japan and comfort women statues keep going up in the U.S. Meanwhile Japan should recognize that its imperialism in the first half of 20th century was the root cause of women’s suffering.

◇ ◇ ◇ ◇ ◇ ◇ ◇ ◇ ◇ ◇

Footnote: Professor Park Yuha’s book “Comfort Women of the Empire” was banned from publication in South Korea. Professor Park is also being sued for defamation by the anti-Japan lobby and receives death threats from time to time. In South Korea, the government often uses anti-Japan lobby to hunt down people who speak out the inconvenient truth. It is now very difficult for Professor Park to publish anything in South Korea without being persecuted, but her books can be purchased in other Asian countries.

Update: A legal document has been published concerning the case against Professor Park Yuha. It is a 16 page PDF in Korean with an Abstract in English.

LINK to the PDF:

https://parkyuha.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/10.%ed%99%8d%ec%8a%b9%ea%b8%b0.pdf

Here is the Abstract:

A Critical Analysis of the Injunctions on “Comfort Women of the Empire” – Focusing on Seoul East District Court Case 2014kahap10095

Sung-Kee Hong – Professor, Inha University Law School

Abstract: In order for a court to issue a preliminary injunction, strict and clear substantive requirements should be satisfied, and the burden of proof is on the plaintiffs (Supreme Court 2003ma1477). On February 17, 2015, in the case of a restraining order regarding “Comfort Women of the Empire” written by prof. Park, the court ruled that the book shall not be published unless 34 lines were deleted (Seoul East District Court 2014kahap10095). The court was of the opinion that those disputable 34 lines might substantially defame the 9 plaintiffs who used to be comfort women for the Japanese military during Japanese colonialism. Though the case was filed under the names of the 9 ex-comfort women, the actual party seems to be the civic group who nominally supported the comfort women but was very stubborn in its stance for its own interests. “The comfort women” referred to in the book comprises the whole Korean comfort women who had suffered during the Sino-Japanese War in the 1930s and the Pacific War in the 1940s. Accordingly, there seems to be no possibility that the book, which analyzed the pains of the whole Korean comfort women – whose total numbers are not yet known – would damage the reputation of the individual plaintiffs. On the other hand, the 34 lines are not in fact ‘false’ statements in the context of the entire book. Those lines are either opinions or facts of public concern which are closely related to academic freedom and freedom of expression. The court may have been negligent in assessing the substantive requirements and burden of proof.

•논문접수 : 2020. 5. 11. • 심 사 : 2020. 6. 1. • 게재확정 : 2020. 8. 10.

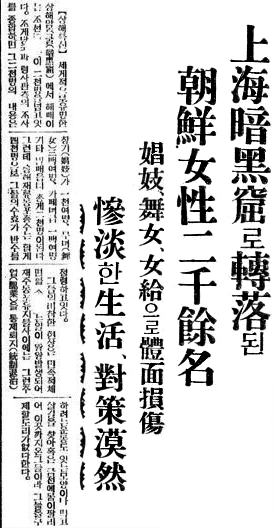

March 7, 1935 동아일보 Dong-A Ilbo

上海暗黑窟로轉落된

朝鮮女性⼆千餘名

娼妓舞女,女給으로體面損傷

慘淡한生活對策漠然

About 2,000 Korean women work in brothels in the slums of Shanghai in China.

Koreans have lost face [their reputation has been damaged] because of these Korean prostitutes who are working abroad. The measures to help them are vague in spite of their miserable lives. It is a shame, but because they are working voluntarily due to their economic problems [in Korea], there is no solution.

(*1)

The following is excerpts from Korean comfort woman Mun Ok-chu’s memoir. Her memoir shows what it was like to be a comfort woman in Burma. (Translated)

버마전선 일본군 위안부 문옥주 문옥주 할머니 일대기

역사의 증언 두번째 이야기

모리카와 마치코 지음

김정성 옮김

2005년 08월 08일 출간

“Myself as a comfort woman for Tate Division deployed in Burma” by Mun Oku-chu

(published August 2005)

(In Mandalay, Burma)

page 63

The soldiers and we had the same thoughts, that is, we must work hard for our emperor. The soldiers gave up their wives, children and their own lives. Knowing how they felt, I did my best to solace them by having conversation with them.

page 68

I prayed for safety of Ichiro Yamada. After two or three of months, the troop unit to which Yamada belonged returned from the front. Yamada returned in good health. He immediately came to the comfort station. He said “I, private first class soldier Yamada, have just come back from the front.” Yamada gave a salute to me. We hugged in full of joy. Such a day was so special that the comfort station owner Matsumoto (a Korean from Daegu) closed business for the day. The comfort station was full of excitement, and we, comfort women, contributed 1 yen per woman to hold a big party for them.

page 75

I saved a considerable amount of money from tips. So I asked a clerical staff whether or not I could have a saving account and put the money in the account. His reply was positive. I knew that all the soldiers put their earnings in the saving accounts in the field post office, so I decided to put my money in the saving account. I asked a soldier to make a personal seal and put 500 yen in the account. I got my savings passbook and found 500 yen written on the passbook. I became the owner of the savings passbook for the first time in my life. I worked in Daegu as a nanny and a street seller from the childhood but I remained poor no matter how hard I worked. I could not believe that I could have so much money in my saving account. A house in Daegu cost 1,000 yen at the time. I could let my mother have an easy life. I felt very happy and proud. The savings passbook became my treasure.

page 98

Ichiro Yamada came to see me once a week and I was in a great mood on that day from the morning. But if he did not show up on his once a week holiday, I became so worried wondering if he was killed by the enemy that I could not work properly. He made me worry so much.

(In Rangoon, Burma)

pages 106~107

I was able to have more freedom in Rangoon than before. Of course, not completely free but I could go out once a week or twice a month with permission from the Korean owner. It was fun to go shopping by rickshaw. I can’t forget the experience of shopping in a market in Rangoon. There were lots of jewelry shops because many jewels were produced in Burma, and ruby and jade were not expensive. One of my friends collected many jewels. I thought I should have a jewel myself, so I went and bought a diamond.

page 107

I often went to see Japanese movies and Kabuki plays in which players came from the mainland Japan. I enjoyed watching players change costumes many times and male players portray women’s roles. I became a popular woman in Rangoon. There were a lot more officers in Rangoon than near the frontlines, so I was invited to many parties. I sang songs at parties and received lots of tips.

(In Saigon, Vietnam)

pages 115~118

It was finally time to return home. I went to Saigon via Thailand. The ship was to depart from Saigon. Then Tsubame said “I had a nightmare in the morning about my mother vomiting blood. I am afraid that something unlucky will happen, so I will not return to Korea.” Hiroko, Kifa and Hifumi agreed with Tsubame saying “We will not go back to Korea, either.”

page 120

When I went to a cabaret where Japanese military men hung out, navy pilots were there. Some of them asked me “Why are you still here?” I replied “I am still here because I don’t want to go home. I want to go back to Rangoon.”

page 121

I put on a pair of high heels, a green coat and carried an alligator leather handbag. I swaggered about in a fashionable dress. No one could guess that I was a comfort woman. I felt so happy and proud.

(Back In Rangoon)

page 123

A military man came on a bicycle and asked me “Hi Yoshiko, can you ride a bicycle?” I replied “No, I can’t.” He asked “Would you like to learn how to ride?” I learned with pleasure. I rode it smoothly through the town of Rangoon. I didn’t see any other women on bicycles. People on the street looked back at me. It was fun for me to go to the town of Rangoon. I talked with people in Burmese, Japanese and Korean. I had no difficulty communicating when I shopped.

page 126

I killed a non-commissioned officer who was drunk and held the sword against me. I won acquittal as legitimate self-defense, and many military men were pleased with that court decision.

page 137

I withdrew 5,000 yen from my saving account and sent it to my mother.

http://scholarsinenglish.blogspot.jp/2014/10/former-korean-comfort-woman-mun-oku.html

(*2)

The following is a U.S. military report. Except for the part where it says “Japanese agents recruited women and Japanese housemasters operated comfort stations,” this report is accurate. It should have said “ethnic Korean agents recruited Korean women and Korean housemasters operated comfort stations.” The U.S. military interrogator must have thought they were Japanese because their surnames were Japanese.

http://ww2db.com/doc.php?q=130

(*3)

The following article reports that Professor Ahn Byong Jik of Seoul University had recently discovered a diary written by a Korean comfort station manager. Comfort station owners that appear in his diary are Oyama from Seoul Korea, Ohara from Daegu Korea, Uchizono from Korea, Murayama from Korea, Yamamoto from Daegu Korea, Nozawa from Korea, Matsumoto from Daegu Korea, Kinoshita origin unknown, Mitsuyama from Korea, Kanai origin unknown, Oishi from Korea, Nishihara from Korea. So although they all had Japanese surnames, most of them – if not all – were Koreans.

The diary also mentions that whenever they needed more comfort women, owners themselves went back to Korea to recruit women.

Professor Ahn Byong Jik confirms in this article that Korean comfort women were recruited by Korean prostitution brokers, not by Japanese military.

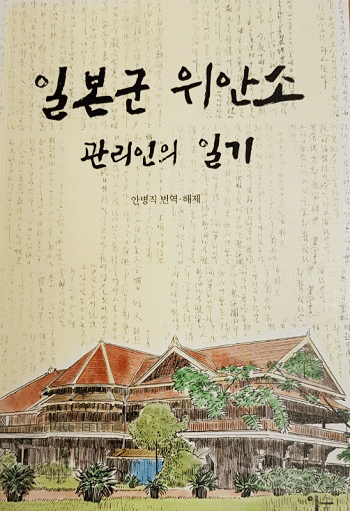

The Korean comfort station manager’s diary book cover:

The Korean comfort station manager’s diary is available in Korean, Japanese and extracts in English.

Download Diary in Japanese as a PDF:

http://nadesiko-action.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/comort_women_diary.pdf

34 page excerpt in English from “The Diary of a Japanese Military Comfort Station Manager” (excerpted and translated from Japanese translation by Hori Kazuo, professor at Kyoto University, and Kimura Kan, professor at Kobe University, to English by Haraguchi Yoshio, former history teacher at Japanese high school, July 20th, 2018)

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xUn-lWuIoWDMqgByTDeo61Cm4z5GMfLh/view

___

Korean’s war brothel diaries offer new details

JIJI

August 13, 2013

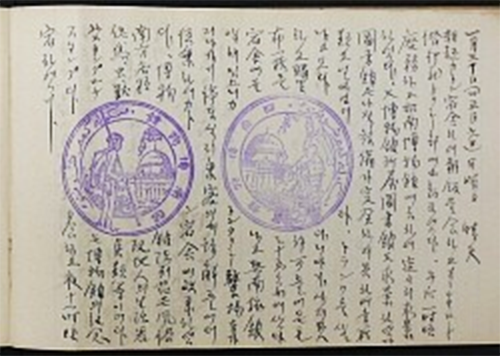

SEOUL – The diaries of a Korean man who worked in wartime brothels for Japanese soldiers in Burma and Singapore during World War II have been found in South Korea.

Researchers believe the diaries, the first ever found that were written by someone who worked at a “comfort station,” are authentic and provide actual details of the brothels and the lives of “comfort women.”

They also show that the Imperial Japanese Army was involved in the management of the facilities, which the Japanese government acknowledged in a 1993 statement by then-Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono.

The Korean man worked as a clerk in the brothels. Born in 1905, he died in 1979 before the comfort women became a thorny issue between Japan and South Korea.

A South Korean museum obtained the diaries covering 1922 to 1957, with several years missing, from a secondhand bookstore.

Ahn Byung-jik, a professor emeritus at Seoul National University, examined the portion for 1943 and 1944 jointly with two Japanese researchers, Kyoto University professor Kazuo Hori and Kobe University professor Kan Kimura. Their joint research will be published in South Korea in the near future.

One passage describes how two prostitutes who had quit because of their marriages had been ordered to return by army logistics. He also said he submitted daily reports to the logistics command.

The man noted that the manager of one of the comfort stations was a Korean from Chungju in the central part of the peninsula.

He wrote that he had withdrawn ¥600 from a prostitute’s account and remitted it at a post office on her behalf, indicating that comfort women were paid.

In a glimpse of their daily lives, the man wrote that “comfort women went to see a movie screened by the railroad unit.”

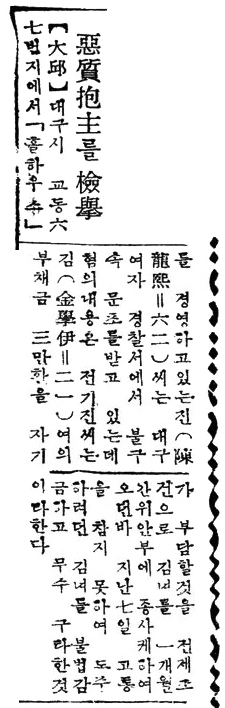

The diaries are “highly credible,” Kimura said, noting there was little possibility of alterations because the man died before the comfort women issue became a source of contention.