Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field

1st Edition

Edited by Benjamin Zablocki and Thomas Robbins

Misunderstanding Cults provides a uniquely balanced contribution to what has become a highly polarized area of study. Working towards a moderate ‘third path’ in the heated debate over new religious movements (NRMs) or cults, this collection includes contributions both from scholars who have been characterized as ‘anticult’ and from those characterized as ‘cult apologists.’ The study incorporates diverse viewpoints as well as a variety of theoretical and methodological orientations, with the stated goal of depolarizing the discussion over alternative religious movements. A large portion of the book focuses explicitly on the issue of scholarly objectivity and the danger of partisanship in the study of cults.

The collection also includes contributions on the controversial and much misunderstood topic of brainwashing, as well as discussions of cult violence, child rearing within unconventional religious movements, and the conflicts between NRMs and their critics. Thorough and wide-ranging, this is the first study of new religious movements to address the main points of controversy within the field while attempting to find a middle ground between opposing camps of scholarship.

About the Authors

Benjamin Zablocki is a professor in the Department of Sociology at Rutgers University.

Thomas Robbins is an independent scholar and lives in Rochester, Minnesota.

Series: Heritage

Paperback: 538 pages

Publisher: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division; 1 edition (December 1, 2001)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0802081886

ISBN-13: 978-0802081889

Contents

Preface ix

Caveat xiii

Introduction: Finding a Middle Ground in a Polarized Scholarly Arena 3

Benjamin Zablocki and Thomas Robbins

PART ONE: HOW OBJECTIVE ARE THE SCHOLARS?

1 ‘O Truant Muse’: Collaborationism and Research Integrity 35

Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi

2 Balance and Fairness in the Study of Alternative Religions 71

Thomas Robbins

3 Caught Up in the Cult Wars: Confessions of a Canadian Researcher 99

Susan J. Palmer

4 Pitfalls in the Sociological Study of Cults 123

Janja Lalich

PART TWO: HOW CONSTRAINED ARE THE PARTICIPANTS?

5 Towards a Demystified and Disinterested Scientific Theory of Brainwashing 159

Benjamin Zablocki

6 Tactical Ambiguity and Brainwashing Formulations: Science or Pseudo Science 215

Dick Anthony

7 A Tale of Two Theories: Brainwashing and Conversion as Competing Political Narratives 318

David Bromley

8 Brainwashing Programs in The Family/Children of God and Scientology 349

Stephen A. Kent

9 Raising Lazarus: A Methodological Critique of Stephen Kent’s Revival of the Brainwashing Model 379

Lorne L. Dawson

10 Compelling Evidence: A Rejoinder to Lorne Dawson’s Chapter 401

Stephen A. Kent

PART THREE: HOW CONCERNED SHOULD SOCIETY BE?

11 Child-Rearing Issues in Totalist Groups 415

Amy Siskind

12 Contested Narratives: A Case Study of the Conflict Between a New Religious Movement and Its Critics 452

Julius H. Rubin

13 The Roots of Religious Violence in America 478

Jeffrey Kaplan

Appendix 515

Contributors 521

Contributors

Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi received a PhD in clinical psychology from Michigan State University in 1970, and since then has held clinical, research, and teaching positions in academic institutions in the United States, Europe, and Israel. He is currently professor of psychology at the University of Haifa. Among his best-known publications are Despair and Deliverance (1992), The Psychology of Religious Behaviour, Belief, and Experience (1997), and the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Active New Religions (1998).

Janja Lalich specializes in the study of charismatic relationships, ideology, and social control, and issues of gender and sexuality. She received her PhD from the Fielding Institute in Santa Barbara, California, and currently teaches in the Department of Sociology at California State University, Chico. Her works include ‘Crazy’ Therapies; Cults in Our Midst; Captive Hearts, Captive Minds; and Women Under the Influence: A Study of Women’s Lives in Totalist Groups. Her forthcoming book. Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Commitment (University of California Press), is based on a comparative study of Heaven’s Gate, the group that committed collective suicide in 1997, and the Democratic Workers Party.

Benjamin D. Zablocki is a professor of sociology at Rutgers University. He received his PhD from Johns Hopkins University and has taught at the University of California – Berkeley, California Institute of Technology, and Columbia University. He has published two books on cults, The Joyful Community (University of Chicago Press 1971) and Alienation and Charisma (The Free Press 1980). He has been studying religious movements for thirty-six years, with sponsorship from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. Currently he is working on a twenty-five-year longitudinal study of religious belief and ideology.

Stephen A. Kent is a professor in the Department of Sociology, University of Alberta. He received his BA in sociology from the University of Maryland (College Park) in 1973; an MA in the History of Religions from American University in 1978, and an MA (in 1980) and PhD in Religious Studies from McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario) in 1984. From 1984 to 1986 he held an Izaac Walton Killam Postdoctoral Fellowship in the Department of Sociology. He has published articles in Philosophy East and West, Journal of Religious History, British Journal of Sociology, Sociological Inquiry, Sociological Analysis, Canadian Journal of Sociology, Quaker History, Comparative Social Research, Journal of Religion and Health, Marburg Journal of Religion, and Religion. His current research concentrates on nontraditional and alternative religions.

etc.

Preface

We deliberately gave this book an odd title. Misunderstanding Cults is not, of course, a guidebook on how to misunderstand cults. Rather it is a book about what makes cults (or ‘new religious movements’ as they are sometimes called) so hard to understand. Its purpose is to better comprehend why these groups are so often comically or tragically misunderstood by ‘experts’ as well as by the general public. Specifically, we have focused on the problem of academic misunderstanding and its correlative polarization of academic experts into opposing camps holding mutually hostile points of view. Our hope is to make a contribution towards overcoming this polarization and introducing a greater degree of cooperation and humility into the study of a subject matter that would be difficult to comprehend even under more collegial investigatory conditions.

Polarization in the study of cults has fostered a toxic level of suspicion among scholars working in this field. This polarization, for the most part, is between those focusing on ‘macro-meso’ issues and those focusing on ‘meso-micro’ issues. Social scientists tend to distinguish three levels of social analysis. The macro level is concerned with the largest social aggregates: governments, societies, social classes, and so on. The micro level is concerned with the smallest social units: individuals and very small groups such as nuclear families. The meso level is concerned with intermediate-sized social groupings such as neighbourhoods, cities, business firms, denominations, sects, and cults. Unfortunately, it is rare for social scientific theories to span all three of these levels simultaneously, although just such breadth is what is called for by the puzzle of cults. Between the macro-meso specialists, whose chief concern has been the problem of repressive over-regulation of cults by government and society, and the meso-micro specialists, whose chief concern has been the problem of cultic exploitation of individual devotees, there has been little trust and little mutual respect. The historic reasons for this tension will become clear to anyone reading this book.

There is a need to shake people out of comfortable oversimplifications. Squabbles at the level of ‘Cults are evil!’ ‘No! Cults are OK,’ do nothing to further our understanding of these complex sociocultural phenomena. Cults are a genuine expression of religious freedom deserving toleration. At the same time, they are opportunities for unchecked exploitation of followers by leaders deserving civic scrutiny. As fragile new belief systems, they need the protective cover of benign neglect by the state. But as religious movements, it is always possible that a few of them may turn into potential incubators of terrorism or other forms of crime and abuse.

This situation has made it a challenge to us, as editors, to assemble a dozen authors to write chapters for the book from a wide range of viewpoints. We recognize that many of these authors have had to endure criticism from some of their colleagues for ‘sleeping with the enemy,’ as it were. A few scholars who originally intended to write chapters for this volume actually dropped out of the project because of its controversial nature. We therefore want to gratefully acknowledge the courage of our authors in enduring this criticism in pursuit of higher goals of cooperation and collegiality as well as answers to the intriguing puzzles caused by the cult phenomenon.

In the early 1990s, Thomas Robbins was loosely affiliated with the macro-meso scholars and shared their concerns about the dangers of statist religious repression. Benjamin Zablocki was loosely affiliated with the meso-micro scholars and shared their concerns about the dangers of economic, physical, and psychological abuse of cult members by cult leaders. But the two of us found that we shared a worry about the unusually high degree of polarization that plagued our field. Through many long discussions and exchanges of letters and ‘position papers,’ the two of us were gradually able to move to a more tolerant understanding of each other’s concerns. This book grew directly out of our enthusiasm about the positive effects of our private dialogue, and out of a desire to take this dialogue ‘wholesale’ by promoting the value of a moderate and inclusive perspective with our colleagues and with the interested general public.

This book itself cannot entirely overcome the polarization that has long blighted our field of study. Although most of our authors have tried to modulate their perspectives, we are painfully aware that almost every reader will find a chapter that will offend. At most we have made a beginning: to paraphrase Joni Mitchell, ‘We’ve looked at cults from both sides now, from up and down, but still, somehow, it’s mostly cult’s illusions that we’re stuck with.’ Further progress in understanding this subject matter will require both patience and a great deal of additional collaboration. It will also require receptive listening to the viewpoints of others with whom we may initially disagree.

We would like to acknowledge the help of several colleagues with whom we discussed our project. These include William Bainbridge, Rob Balch, Eileen Barker, Michael Barkun, Jayne Docherty, Mimi Goldman, Massimo Introvigne, Michael Langone, Anna Looney, Phillip Lucas, John Levi Martin, James Richardson, Jean Rosenfeld, Ramon Sender, Thomas Smith, and Lisa Zablocki. We don’t mean to imply that all of these people completely endorsed this project. Some were highly critical and some made suggestions that were ignored. So it is more than a matter of ‘preface boilerplate’ to state that none of them is in any way responsible for the points of view expressed in these pages. But all of them did help us approach the task of editing this volume with a richer and more inclusive perspective.

We also wish to acknowledge the assistance of a number of people who helped us in various ways. Jean Peterson provided valuable clerical and computing assistance to Thomas Robbins during this project. Melissa Edmond, Lauren O’Callaghan, and Maria Chen provided diligent editorial assistance to Benjamin Zablocki. Virgil Duff, our editor at the University of Toronto Press, has been supportive and helpful from the beginning. Two anonymous readers have offered constructive suggestions many of which we have attempted to incorporate into our revisions, and which we believe have strengthened the organization of the volume.

Caveat

Of necessity, given its aims, this is a controversial book. Be warned that almost every reader will take issue with at least one of the essays we have included. The principal aim of the book is to restore a moderate perspective to the social scientific study of cults. Our strategy for achieving this goal has been to invite essays from as wide a range of scholarly points of view as possible, not only from moderates but from the polarized extremes as well. We believe that only by giving public voice to controversy can some degree of consensus and compromise begin to emerge. Hopefully, therefore, it will be understood that the opinions expressed in these chapters are those of each author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors.

An additional issue of fairness arises in those chapters in which scholars take aim, not at other scholars but at various specific cults or anticult organizations. Two points need to be made about such criticisms. The first point is that all the data reported in this book are historical, and therefore none of the criticisms of specific organizations should be taken to apply necessarily to any of these organizations at the present time. The second point is that, even so, a fair-minded reader may very well wish to learn the point of view of the organization being criticized before evaluating the plausibility of the criticism. We, the editors, strongly urge readers to take the trouble to do so. One point upon which we both wholeheartedly agree is that, ultimately, nothing but good can come from exposure to the widest variety of intellectual perspectives. As an aid to the reader in gaining access to these points of view, we have included an appendix listing of publications and websites written by or maintained by the various cults and anticult organizations discussed in this book.

Finally, we wish to emphasize a point we repeat at greater length in the introduction. The word cult in this volume is not meant to be evaluative. The word existed as an analytic category in the social sciences long before it was vulgarized in the mass media as an epithet. In our opinion, simply describing an organization as a cult does not, in itself, imply that we believe that the organization is good or bad or that its ideology is authentic or inauthentic. Indeed we consider these sorts of judgments outside the analytic realm of competence of the social scientist.

Benjamin Zablocki

Thomas Robbins

page 3

Introduction: Finding a Middle Ground in a Polarized Scholarly Arena

Benjamin Zablocki and Thomas Robbins

Every once in a while, cults make news in a big way.1 Jonestown, Waco, Aum Shinrikyo, and Heaven’s Gate are only some of the keywords that remind us of the capacity of religious and other ideological movements to act in ways that leave much of the public thunderstruck. When bewildering events happen, there is a natural tendency to turn to ‘experts’ to explain what at first seems inexplicable. This is a well-established role of the academic expert in our society. But the striking thing about cult events is that the experts rarely agree. This is a field with little or no convergence. The more channels you turn to on your TV set, the more different contradictory opinions you run into. Eventually, the public loses interest and goes away, either with pre-existing prejudices reinforced or with the conclusion that some things are just beyond explanation and cults are one of them. This book is an attempt to discern what it is about religious cults that make them so intractable to expert analysis and interpretation. What is it about cults that makes it so easy for even the experts to misunderstand them?

This book has developed out of a series of conversations between its editors. Both of us have long deplored the divisive polarization, which, at least until recently, has plagued the academic study of religious movements.2 This polarization, into a clique of academic ‘cult bashers’ on the one hand and a clique of academic ‘cult apologists’ on the other, has impeded learning and has added confusion rather than clarity to a class of phenomena already beset with more than its share of confusion and misunderstanding. It is the goal of the editors of this book to encourage and facilitate the carving out of a moderate middle ground for scholars who wish to see charismatic religious movements in shades of grey rather than as either black or white. To aid in this effort, we have deliberately recruited contributors to this book from both extremes,3 as well as from scholars whose work is already considered more moderate.

Most books about cults, whether monographs or collections of essays, represent a single point of view or a narrow band on the viewpoint spectrum. Even when a contrarian voice is solicited, the context is clearly one of tokenism. One divergent point of view helps to set off and define the points of view of all the rest. This book is very different in two ways: (1) we have invited essays from scholars representing all of the various viewpoints within the social sciences; (2) we have urged all of our contributing essayists to eschew polemics and treat perspectives other than their own with respect and seriousness. Although this book by itself cannot overcome the residual polarization that still lingers in the study of cults, it may accomplish two important prerequisites. First, we hope it will get scholars talking to one another who in the past have always avoided reading each other’s work. Second, we hope it will enable the informed public to understand that the reason we misunderstand cults is not that they are intrinsically beyond comprehension, but rather that they pose challenges that have thus far divided scholars but which careful research may help to overcome.

Academic Polarization

We have made an assertion that perhaps will not seem immediately evident to many: that the academic study of new religious movements has been sharply divided into two opposed camps in a way that is highly detrimental to intellectual progress in the field. Probably, we need to document this assertion before attempting to draw certain conclusions from it. There is a cluster of scholars who have tended to be labelled (by their opponents) as ‘cult apologists’ who have generally taken a tolerant attitude of qualified support towards these groups. There is another cluster of scholars who have been labelled (again by their opponents) as ‘cult bashers’ who have generally taken a negative and critical attitude towards these same groups.

Until a few years ago, there was little alternative but to be a part of one or the other of these groupings. In recent years, however, a moderate interdisciplinary position has slowly and painfully begun to develop. Examples of this can be seen in the recent work of Robert Balch and John Hall in sociology, Michael Barkun in political science, and Marc Galanter in psychiatry, among others. So it should be emphasized that we use the terms ‘cult apologist’ and ‘cult basher’ in this book mainly in a historical sense;4 thus, the use of these terms is not indicative of our validation of the stigma embodied in them. Nevertheless, because the present situation cannot be understood without understanding the roots of this historical polarization, we will continue to use these terms in referring to these two intellectual clusters.

Evidence for the existence of these clusters can be seen in the very terms ‘cult’ and ‘new religious movement.’ The use of either of these terms is a kind of shibboleth by which one has been able to know, with some degree of accuracy, how to classify a scholar in this field. In the past, it was only the ‘apologists’ who tended to use the latter term; the bashers preferred the former term. The difference of opinion is not just a matter of linguistic style. The term cult is an insult to those who are positively disposed towards these groups or who feel that it is important to actively support their right to exist even while perhaps deploring some of their practices. The term new religious movement is a misleading euphemism to those who are negatively disposed. It is also thought to be misleading in that it ignores political and psychotherapeutic cults, implying, as it does, that all such groups are religious in nature.

We will try to display our own moderate colours by referring to these groups sometimes as cults and sometimes as new religious movements (NRMs). In neither case is it our intention to be judgmental. Historically the word cult has been used in sociology to refer to any religion held together more by devotion to a living charismatic leader who actively participates in the group’s decision-making than by adherence to a body of doctrine or prescribed set of rituals. By such a definition, many religions would be accurately described as cults during certain phases of their history, and as sects, denominations, or churches at other times. The mass media sometimes make a distinction between ‘genuine religions’ and cults, implying that there is something non-genuine about the latter by definition. We do not share the implicit bias that seems to be embedded in this usage. Nor, by calling a group an NRM, do we necessarily imply that the group must be benign.

Polarizing issues in this field are not limited to the cult versus NRM controversy. Attitudes towards the concept of ‘brainwashing’ and towards the methodological device of making use of ex-member (apostate) accounts as data are two of many other issues that divide scholars into these two camps. Beliefs about the advisability of scholars accepting financial support from NRMs is still another issue upon which opinions are sharply divided.

The historical reasons for the development of this polarization are too complex to be reviewed here, especially as they have been discussed extensively elsewhere by ourselves and others (Anthony and Robbins 1995; Zablocki 1997). Much of it has to do with a quarter-century of involvement by scholars from both camps in high-stakes litigation involving these religious groups. The law courts, with their need for absolutes and their contempt for scholarly ambivalence, helped to push both those who started with mildly positive dispositions towards cults into the extreme posture of the ‘cult apologist’ and those who started with mildly negative dispositions towards these same NRMs into the extreme posture of the ‘basher.’5

If these events had merely produced a tendency towards a bipolar distribution of attitudes in this scholarly subdiscipline the results would have been bad enough. But even worse was the crystallization of these two loosely affiliated clusters of scholars into what Fleck has called ‘thought communities’ (Fleck 1979). Through one group’s involvement with the organized anticult movement and the other’s attempt to establish or sustain hegemony in key scholarly organizations of social and behavioral scientists, these clusters gradually crystallized into mutually reinforcing, self-perpetuating scholarly communities. Rather than combining perspectives to get closer to the truth, these communities came to define themselves, increasingly, in terms of words that could or could not be uttered and ideas that could or could not be thought about. Hardened positions on such issues as brainwashing or apostasy, for example, exemplify Fleck’s notion of the ‘fact’ as ‘a signal of resistance (by a thought community) opposing free arbitrary thinking’ (101). Dialogue practically ceased between the two camps for a while, as each preferred to talk mainly to those who shared the same perspective.

In the manner of insular thought communities throughout history, these sought to reinforce solidarity not only by mutual intellectual congratulation of comrades in the same camp but by vilification of those in the other camp. In this way, the rivalry came to take on a bitter emotional dimension that served to energize and exacerbate the initial cognitive disagreements (Allen 1998).

Each side has had its poster child depicting the horrors that the other side was able somehow to callously condone. For the ‘apologists,’ it was the image of the sincere religious seeker kidnapped by unscrupulous deprogrammers and thrust into a dark basement of an anticult-movement safe house to be inquisitorially pressured to renounce her faith. The fact that the most notorious of the early coercive deprogrammers happened to be a husky African-American male and the archetypical religious kidnappee was generally depicted as a frail, sincere, but very frightened white female helped to assure that the revulsion caused by this portrait was never overly tepid, although this, of course, was never mentioned out loud. For the ‘bashers’ the poster image was just as heart-rending; a little girl looking trustingly up at her hopelessly brainwashed daddy while he feeds her poisoned Kool-Aid at the behest of his ranting paranoid prophet, or a little boy being beaten half to death by the community elders for his inability to memorize the weekly portion of the Bible.

We don’t mean to be dismissive of these emotional concerns. Overblown as the symbols have become, each has its roots in instances of very real suffering and injustice. The problem for the academic discipline is to be found not in the emotional sympathy of its practitioners, which is commendable, but in the curious fact that these two emotional stimuli have come to be seen as mutually exclusive. Caring about one required that you be callous about the other. In fact, our own personal litmus test in our quest for scholars who could be called ‘moderates’ is precisely the capacity to be moved to sympathy by the poster children of each of the two thought communities, i.e., to engage in what Robbins, in his chapter in this volume, calls ‘pluralistic compassion.’ Gradually, a critical mass of such moderate scholars has begun to emerge.

Through twenty-five years of wrangling, both in journals and in courtrooms, the two thought communities we have been discussing have worked out internally consistent theoretical and methodological positions on a wide variety of issues regarding cult research. Although a number of scholars have come forth professing to be moderates (Bromley 1998, 250), it is not yet nearly as clear how such a moderate stance will eventually come to be defined in this field.

Fortunately, we have a good role model to help us get started. The field of new religious movements has not been the only area in the social sciences that has ever been plagued by such divisions. In fact the larger and more general subdiscipline known as ‘social movements’ gives us some clues concerning the repairs we must make. Almost a decade ago, sociologist John Lofland published a paper taking his colleagues in the Social Movements field to task for counterproductive tendencies similar to the ones we have been discussing here (Lofland 1993). The situation he describes is not identical, of course. The role of litigation was much less of a factor in his field, for example. Nevertheless, the suggestions he makes can be helpful to us.

Lofland distinguishes two alternative mind-sets for studying social movements. He calls one of them the ‘theory bashing’ mind-set and the other the ‘answer-improving’ mind-set. The theory bashing mindset is defined as: ‘a set of contending ‘theories’ whose respective merits must be assessed; a set of constructs that must be pitted against one another; [and] a field of contenders in which one professes allegiance to one, has alliances with others, and zealously pursues campaigns to discredit and banish yet others’ (Lofland 1993: 37). In contrast, the answer-improving mind-set is defined as one in which the study of social movements is constructed as ‘a set of questions for which we are trying to provide ever-improved answers through processes of successive revision in order to delete erroneous aspects of answers and to incorporate more accurate elements into answers. Rather than aiming to discredit or vindicate a ‘theory’ one aims to construct a more comprehensive, accurate, and powerful answer to a question’ (37-8).

A Moderate Agenda

Our argument is that just such a shift in mind-set is precisely what is needed to create and sustain a moderate third path for scholars studying new religious movements. Although easy to envision, such a shift will be tricky to implement. However, the effort is worth it for two reasons. First, the study of religion is a very difficult business and none of us has all the answers. We will make more progress once we recognize that none of our paradigms comes even close to being able to claim to be the master paradigm. We work within a multi-paradigmatic discipline precisely because every single one of our research paradigms is severely limited. Second, as David Bromley (1998) has pointed out, the study of new religious movements has been marginalized by the rest of sociology precisely because of our lack of consensus on so many key issues. Establishing a moderate alternative is essential if we expect our area of research to be taken seriously by colleagues outside the field.

It seems to us that five steps are involved in such a process. The first is a move in the direction of paradigmatic toleration, including a recognition that no one paradigmatic approach can hope to capture the full complexity of religious movements. The second is a move in the direction of greater consensus and precision in conceptual vocabulary. The third is a move towards agreement on a set of principles regarding respect for scholar privacy and demand for scholar accountability in the research process. The fourth is a move towards agreement on a set of principles regarding respect for the privacy of the religious movements we study, and the legitimacy of the demand for their accountability. The fifth, and perhaps most controversial, is a move towards disestablishing the primacy that policy issues have assumed over intellectual issues in our field. That is not to say that policy issues and policy advocacy should be declared illegitimate, but rather that they should be relegated to their traditional position as secondary to our primary academic function which is to observe and to record.

Paradigmatic Toleration

Of the five steps that we mentioned, the most important is the move towards paradigmatic toleration. It is generally well established that there is no master paradigm that effectively organizes theoretical inquiry in sociology. Rather, sociology is acknowledged to be a multi-paradigmatic discipline at this point in its evolution (Effrat 1972; Friedrichs 1970). In most areas of sociology it has been argued that these multiple paradigms are at least, nevertheless, unified by what Charles Lemert (1979:13) has called homocentrism, ‘the … idea which holds that man is the measure of all things.’ But the sociology of religion is perhaps the only redoubt within the discipline of nonhomocentric paradigms as well, making the multiplicity that we have to deal with even richer and more bewildering.

How does one cope with working within a multiparadigmatic discipline? Does one treat it as a burden or an opportunity? Is the idea to strive for hegemony for one’s own paradigm or an atmosphere of mutual toleration or even of cooperation? It was Robert Merton’s contention that there need not be contention among our various paradigms. He argued that they are ‘opposed to one another in about the same sense as ham is opposed to eggs: they are perceptively different but mutually enriching’ (Merton 1975: 30). This is a notion upon which we hope that a moderate position in our field can crystallize. Since none of us has made all that impressive progress in understanding NRMs from within our own paradigms, maybe coming at them with multiple cognitive approaches will allow us to do better.

The specific paradigms that do battle within the sociology of cults are too numerous and the various alliances too complex to be dealt with here comprehensively. We will have to make do with just one example. No doubt the most egregious example of the paradigmatic intolerance and conflict that has plagued the study of religion is that between the positivists and the phenomenologists. (The former perspective is sometimes embodied in controversial ‘rational choice’ models of religious behaviour.) Each has a reputation for being a pretty arrogant bunch. However, think for a minute what it means to be studying religion, to be trying to understand the actions of people who are motivated by their relation to the sacred, to be attempting to participant-observe the ineffable, or at least the consequences of the ineffable, and then to report on it. Such undertakings ought to make us humble. They ought to make us understand that it is highly unlikely that either a pure positivist approach or a pure phenomenological approach will come away with all the answers. Such undertakings seem to us to cry out for all that the right brain can tell the left brain, and vice versa. Under these circumstances, it is not unreasonable for each of us to consider giving up our own allegiance to paradigmatic chauvinism.

Conceptual Precision and Consensus

A symptom of the extreme polarization of this field is that certain words have become emotionally charged to an abnormally high degree. Although scholars in all fields tend to argue about conceptual definitions of terms, the extent to which vocabulary choice determines status in the NRM field would delight an expectation-states theorist. To paraphrase Henry Higgins, ‘The moment that a cult scholar begins to speak he makes some other cult scholar despise him.’ Why do people get so worked up over the question of whether to call certain groups cults or NRMs, or certain processes brainwashing or resocialization, or certain people apostates or ex-members?

Choices among these words are extremely important to some people. Their use is often taken as the external sign of membership in one or another rigid thought community. Therefore, it follows that a moderate thought community needs its own identifying vocabulary. We would have hoped that Stark and Bainbridge (1996) might have at least partially satisfied that need with the dozens of painstaking definitions they offered in their comprehensive theory of religion. But a shared vocabulary is of no value unless people agree to use it, and this has not yet happened.

We speculate that the structural resistance to the adaptation of a consensually accepted moderate vocabulary is to be found in large part in the cosiness of using the vocabulary of one of the two polarized thought communities. When Zablocki speaks of brainwashing he immediately has a hundred allies in the anticult movement, all of whom are inclined to speak favorably of his work even if they have never read it (and even though some of them might be horrified if they ever actually did read it). When Robbins calls a group a NRM instead of a cult he is thereby assured that he is recognized as a member in good standing of that valiant confraternity that has pledged itself to the defense of religious liberty. Such warm fuzzies are difficult to relinquish merely for the sake of increased intellectual vitality.

It might just be possible to adopt a ‘bureaucratic’ solution to this problem. We would be happy to abide by a set of rational standards governing conceptual vocabulary, and we imagine that many of our colleagues would as well. Many of our colleagues have told us that convening a committee to propose a set of standards on the use of conceptual terms in the study of NRMs is not practical. We don’t see why. If we restrict ourselves for the moment to those writing in English, there are probably not many more than a couple of hundred scholars actively studying cults at the present time. And probably fewer than fifty of these have any serious interest in actively creating the kind of moderate thought community that we are proposing. It seems to us that these numbers are small enough to allow us to hope that a working committee of four or five representatives might be able to speak for them.

Respect for Scholarly Privacy and Demand for Scholarly Accountability

One of the most painful consequences of the polarization of the NRM field is the lack of trust that has developed among scholars in opposing camps. Generally this is expressed in the form of questioning the motivations of specific writings or specific research projects. In extreme cases, the charge of selling out for money may also be levelled.

Honest differences of opinion regarding professional norms tend to become amplified in their stridency because the arguments tend to be expressed as ad hominem attacks, and they therefore evoke strong emotional responses. It’s hard for two scholars to even talk to each other if one feels accused of something as crass as selling out for money. On the other hand, it is hard to discuss objectively the possible distortive effects of large amounts of money coming into the field without some people feeling personally attacked.

A closely related issue has to do with affiliations of scholars with government agencies that regulate religious activities or non-government organizations that have a role in controversies regarding cults. All sorts of rumors abound concerning the power, wealth, influence, and backing of organizations on both ‘sides’ such as INFORM (Information on Religious Movements, AWARE (Association of World Academics for Religious Education), CESNUR (Center for Studies on New Religions), CAN (Cult Awareness Network), and AFF (American Family Foundation [now called ICSA, International Cultic Studies Association). Scholars who have worked hard for these organizations may come to identify with them and to consider an attack on one’s organization as an attack on one’s self.

It seems clear to us that a moderate position on these issues has to be based on two complementary principles: the freedom to choose, which needs to be respected, and the responsibility to disclose, which needs to be demanded. It is very unlikely that even a small, moderate group of scholars will ever be able to reach consensus on the issue of from whom and for what one should accept fees. The same is true for the organizations that a scholar chooses to work with. At the same time, in a highly polarized field like this, disclosure is particularly important. If we want to write a book on Scientology, we are the only ones in a position to decide if we feel we can (or wish to) remain objective in this task if we take financial help for this project from Scientology itself, or from the ‘anticult’ AFF. On the other hand, our colleagues have a right to know if we have received support from either of these agencies (or others) so that each of them can decide how to assess possible impacts on our objectivity.

If a cohort of moderate scholars begins the practice of voluntarily adhering to a norm requiring frank disclosure of sources of financial support and organizational affiliations, this will put a lot of pressure on others to do likewise.

Respect for NRM Privacy and Demand for NRM Accountability

In some ways, the greatest gulf between the ‘cult apologists’ and the ‘cult bashers’ is to be found in the question of where to draw the line between the privacy rights and the accountability duties of religious groups. There is consensus only on the rather obvious norm that religious groups must obey the laws of the land and that religious conviction cannot be used as an excuse for criminal behavior.

Once we move beyond this, however, the issues quickly get murkier. Are religious movements more like large extended families with the presumption of comprehensive privacy rights that by custom adhere to kin groups? Or are they more like business corporations or government bureaucracies with the presumption that a wide variety of investigatory probes and regulatory fact-finding demands are simply part of the cost of doing business? The problem is that neither model fits very well. In some respects, cults are like families, and, as long as they mind their own business and keep their lawns mowed, they are entitled to conduct their business in as much privacy as they care to have. To the extent, however, that cults proselytize for new members, solicit funds, or manage business based upon government-approved, tax-exempt status, or raise young children in households where the lines of authority are extra-parental, it may be argued that there needs to be some degree of secular accountability.

It is not, of course, the responsibility of the academic community to draw these lines, nor are we competent to do so. Even so local an issue as private versus public schooling raises problems of enormous complexity such as can only be worked out gradually, mostly by trial and error, between the cult and the society (Keim 1975).

But, as scholars, we do have a responsibility first of all to recognize that religious movements are not all identical in this respect and to learn to distinguish those that fall closer to the private end of the continuum from those that fall closer to the public end. We need further to discuss and work out at least a rough code of ethics regarding the limits of scholarly intrusiveness for religions at various points on this continuum.

As editors of this book, we do not claim to have the answers to these questions. We are simply suggesting that the emerging thought community of moderate cult scholars discuss these issues and consider if it might be feasible to work out some rough guidelines. For what it’s worth, our thoughts on a few of these matters are as follows. First, we rather incline to the view that scholarly infiltration is not justified for private or public religion. A scholar should always be up-front and candid about her research intentions from the time of very first contact.6 Second, fair use of religious documents should be interpreted broadly in the direction of full disclosure for public religions. This remains true even if these documents are regarded as restricted by the movement itself. Stealing documents is of course wrong. But, if as usually happens in cases like these, an apostate or dissident decides to break her vow of secrecy and share esoteric documents with a scholar, then the scholar is not obligated to refuse to receive them. Third, public religions are still religions and are thus inherently more fragile than business corporations or government agencies. The scholar needs to understand that the general public can very easily misunderstand many benign religious practices and lash out defensively against them if they are presented out of context, especially to the media.

De-emphasis on Policy Issues

It was initially an overemphasis on policy issues that polarized this field, and only de-emphasis of these issues will allow it to become depolarized. By this we do not mean that scholars should cease to be interested in the policy outcomes that relate to NRMs, only that their research programs and their writing should not be dominated by policy considerations. As Weber pointed out, scholarship and politics are closely related pursuits, and, for this very reason, they must be kept separate from each other (Weber 1946a, 1946b).7 Those scholars who are moved to work actively in defense of freedom of religious expression need to avoid having this work prevent them as scholars from delving into exploitative, intolerant, and manipulative aspects of the groups they study. Those who are moved to work actively to alert society to cultic excesses need to avoid having this work prevent them as scholars from delving into more attractive aspects of the groups they study and the rewarding and/or volitional dimension of devotees’ involvement.

We do not believe that all of the policy issues dividing scholars in this field are amenable to mediation. The best one can hope for is that some people will come to recognize the validity of the concerns of others even if they think their own are more important. But severe policy disagreements in the NRM area will be slow to disappear. And, inevitably, such policy disputes will spill over into debates over purely academic questions.

It is for this reason that we are arguing that the moderate camp has got to be composed primarily of scholars whose desire to find out the answers to academic questions is significantly greater than their desire to win policy battles. Ironically, such a coalition, by giving up the opportunity to influence cult policy in the short run, may be in the best position to help shape a wise enduring policy towards these groups in the long run by actually improving our understanding of what makes cults tick.

Many older scholars have had their perspectives so decisively shaped by ideological issues that it is doubtful they will ever be willing to have collegial relations with those whose ideologies are on the other side. But as younger people whose attitudes were not shaped during the cult wars of the last twenty-five years enter this field, it is vital that they confront three rather than two options for collegial affiliation. We think it important that a group, however small at first, of scholars whose interests are guided primarily by the answer-improving mind set that we discussed earlier, be available as an alternative to the two warring factions.

Significance of Cult Controversies

Before discussing the specific plan of our book we want to briefly present our view that the issues raised by controversies over cults possess a fundamental sociocultural significance, which would remain salient even if the particular movements to which these issues currently pertain were to decline. James Beckford, an English sociologist of religion, wrote in 1985 that contemporary sociological conflicts over new religious movements raise questions which ‘are probably more significant for the future of Western societies than the NRMs themselves. Even if the movements were suddenly to disappear, the consequences of some of their practices would still be left for years to come’ (1985:11).

Beckford’s comments are reminiscent of some ideas which were expressed earlier by Roland Robertson (1979: 306-7), who noted that authoritarian sects contravene the ‘Weberian principle of consistency’ in that they demand autonomy from the state while arguably denying substantial autonomy to their individual participants. ‘It is in part because of “inconsistency” … [that such groups] … apparently create the necessity for those who claim to act on behalf of society to formulate principles of consistent societal participation’ [emphasis in original]. Authoritarian new religious movements, notes Beckford, represent an extreme situation, which, precisely because it is extreme, throws into sharp relief many of the assumptions hidden behind legal, political, and cultural structures.’ The controversial practices of some NRMs have in effect ‘forced society to show its hand and declare itself’ (Beckford 1985:11).

What Beckford, Robertson, and others (Robbins and Beckford 1993) appear to be putting forward is sort of a Durkheimian argument to the effect that controversial authoritarian and ‘totalistic’ cults and the reactions they are eliciting are serving to pose in sharper relief and possibly to shift the moral boundaries of the contemporary Western societies. Controversies over cults and what to do about them may thus produce a situation in which normative expectations which are generally merely implicit and half-submerged may come to be explicitly articulated and extrapolated, and may be transformed in the process. Cults and their critics may articulate and extrapolate differing versions of implicit moral boundaries (Beckford 1985).

One example of a way in which cult controversies help to highlight such implicit moral boundaries is to be found in the assumptions that cults often challenge about the complex three-way relationships that exist among individuals, communities, and the state (Robertson 1979). A generally unstated value of western culture is that individual persons ought to be able to manifest autonomous inner selves which transcend their confusing multiple social roles (Beckford 1985). Contemporary ‘greedy organizations’ (Coser 1974), including many cults, are perceived by many as contravening modern norms of individualism and personal autonomy. In extreme instances, the devotee of a tight-knit sectarian enclave may appear to the public at large as enslaved, and dehumanized, and as something less than a culturally legitimate person. Such a devotee may be deemed incapable of rational self-evaluation or autonomous decision-making (Delgado 1977,1980,1984). Defenders of high-demand religious movements argue to the contrary that people can find real freedom through surrender to a transcendent religious goal, and that it is really the overbearing ‘therapeutic state’ that threatens true individual choice by discouraging people from choosing religious abnegation of self (Robbins 1979; Shapiro 1983; Shepard 1985).

Another way of looking at the impact of cult controversies on moral boundaries and on the linchpin issue of personal autonomy is in terms of a conflict between the covenantal ethos of traditional close-knit religious sects and early churches, which entails broad and diffuse obligations between individuals and groups, and the modern contractual ethos, which implies more limited, conditional, and functionally specific commitments to groups (Bromley and Busching 1988). Some scholars have argued that much of the recent litigation and legislative initiatives bearing upon ‘cults’ has entailed attempts to impose a modem contractual model on close-knit and high-demand religious groups’ relations with their members (Delgado 1982; Heins 1981; Richardson 1986).

The involvement of scholars in cult-related litigation has been one of the principal sources of polarization in the field (Pfiefer and Ogloff 1992; Richardson 1991; Robbins and Beckford 1993; Van Hoey 1991). The present volume, however, does not deal specifically with legal issues and developments except to the extent that the litigiousness of some cults is able to intimidate some scholars from freely publishing their results. But the essays in this volume do touch on a range of substantive, ethical, and methodological issues arising from the practices of high-demand religious, political, and therapeutic movements. Such issues include, but are not limited to, the following: sexual exploitation of female devotees (Boyle 1998), child rearing and child abuse in totalist milieux (Boyle 1999; Palmer and Hardman 1999), compensation sought for induced emotional trauma, fraud, and psychological imprisonment in totalist groups (Anthony and Robbins 1992, 1995; Delgado 1982), child custody disputes pitting members against former members and non-members (Greene 1989), violence erupting in or allegedly perpetuated by totalist millennialist sects (Robbins and Palmer 1997), and attempts to ‘rescue’ adult devotees through coercive methods (Shepard 1985).

The problem for objectivity is that scholars have gotten involved as expert witnesses (on both sides) in court cases in which such issues have been raised. It has been very difficult for these scholars to then turn around and look at brainwashing (or any of these other issues) from a disinterested scientific perspective apart from the confrontational needs of pending litigation. Disagreements among scholars in this area have been sharp and acrimonious, perhaps irrationally and dysfunctionally so (Allen 1998). As editors of this volume we believe that the explosion of litigation in these areas, however justified in terms of either combating cultist abuses or defending religious freedom, has thus had a net deleterious effect on scholarship and has led to an extreme polarization which has undermined both objectivity and collegiality. Far too much research and theorizing has been done by scholars while experiencing the pressure of participation in pending litigation. Scholarship in other areas is often permeated with disputes, polarization, and recrimination. But polemical excess in this realm has been egregious. To the extent that the litigational perspective continues to dominate, it threatens to make a mockery of the enterprise of scholarship in this field.

The Structure of This Book

In designing this book, we first identified what seem to us the three major sources of confusion and misunderstanding surrounding charismatic religious movements.

The first of these is the role confusion of scholars and helping professionals studying cults. How can they (and should they even try to) investigate groups that specialize in the construction and maintenance of alternate views of reality without being influenced by those views of reality? Can they ever really hope to understand groups with beliefs and practices so fundamentally different from their own?

The second is a type of confusion sometimes found among those participating in religious movements. Are they doing so solely out of their own prior motives or are they being manipulatively influenced by the charismatic organizations themselves? And if the latter, is this influence of the same order (even if perhaps of greater intensity) as that practised routinely in school classrooms and television advertising, and in the preaching of conventional religion? Or is it sufficiently more intense to warrant being called brainwashing or thought reform? Do movements employing manipulative methods of indoctrination and commitment-building represent a significant contemporary social problem and menace?

It should be noted that the controversy over the existence of cultic brainwashing has been the issue which has most sharply divided many of the polarized commentators in this field. They have exhibited little consensus, among themselves, even about what they are fighting over (the existence of a social process or the existence of a social outcome). The one thing they all seem to agree on is that the resolution of this question – Does brainwashing really happen in cults or is it a paranoid and bogus invention of the ‘anticultists’? – is critical for our understanding of cults and their role in our society. For this reason we have devoted by far the greatest amount of space in this volume to a discussion of this subject.

The third is confusion among the public as to what, if anything, to do about these charismatic religious groups. Do they deserve constitutional protection on the same basis as all mainstream religions in the Western world? Or do they require special kinds of surveillance and ‘consumer protection’ in order to protect innocent seekers and innocent bystanders?

This book is organized around groupings of essays devoted to each of these three topic areas. Although all of these issues have been addressed in other books, this volume is unique in two respects. First, it is the only book which brings together these three interrelated sources of confusion within one volume. This is important because the cloud of misunderstanding surrounding these religious movements can best be understood in terms of the interplay of all three of these types of confusion. Second, most other collections of essays have been distinctly inclined towards one or the other of the two divisive academic poles mentioned above. At most there has been a token representation of a scholar from ‘the other side’ and often not even that. This book, by way of contrast, has deliberately solicited contributions entailing a wide range of scholarly perspectives.

The contributors to this volume are mainly drawn from the ranks of senior scholars, with a few promising younger scholars included for generational balance. On the whole the authors on the list have published a cumulative total of over thirty books. They have been actively involved for years in research on controversial movements. They include one scholar who is a member of an esoteric (but not particularly controversial or authoritarian) group, one who is an ex-member of a cult and one who grew up in a cult.

We, the editors, are delighted that a group of scholars with such divergent views were willing to come together within the covers of a single volume. However, we quickly recognized that if we allowed continuing rejoinders and counter-rejoinders until all were in agreement, this book would never have been published. Therefore, we adopted a strict rule that each author’s text would have to stand on its own merits and that no comments by authors on other chapters would be included. Of course, it follows from this that each author in the book is responsible only for his or her own chapter, and that no endorsement of the views of other authors is implied by the mutual willingness of each to be published in the same volume. One set of unique circumstances did require that we relax our ‘no rejoinders’ rule in one instance, which is explained below.

The first section of our volume deals with issues of scholarly objectivity, methodology, and professional norms. Allegations of partisanship, bias, and the shallow quality of fieldwork have recently been debated in a number of published articles (Allen 1998; Balch and Langdon 1998; Introvigne 1998; Kent and Krebs 1998,1999; Zablocki 1997).8 The section is divided into two sets of paired essays. The first pair (chapters 1 and 2) concern the perspectives, motivations, and objectivity of scholars investigating cults. Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi, an Israeli psychologist of religion, presents a hard-hitting critique of the irresponsibility of scholars of religion who appear to have been frequently overly solicitous towards the controversial movements they have dealt with, and to have too often been animated by an imperative of defending and vindicating putatively persecuted cults. These issues are also discussed by a sociologist, Thomas Robbins, who relates the intensity of recent conflict among ‘experts’ on cults to the earlier hot controversy over physically coercive ‘deprogramming’ and to the role of experts in an adversarial system of law and policy-making. Employing a multifaceted analogy between contemporary ‘cult wars’ and agitation in previous decades against domestic communist subversion, the author maintains that rigid orientations of apologetic defensiveness as well as crusading ‘countersubversive’ perspectives tend ultimately to sacrifice objectivity.

The second pair of essays in our first section (chapters 3 and 4) deal with the actual process of field research in the context of somewhat manipulative, close-knit, and often authoritarian and secretive groups. First, Susan Palmer, a researcher of esoteric movements, is frank and humorous in her discussion of the manipulative ploys of some esoteric sects and their desire to co-opt or domesticate the researcher. Seemingly aware of the many pitfalls, Palmer defends the ultimate necessity of first-hand observation of esoteric groups and interviews with current participants. In the second essay the pitfalls related to persuasive impression management on the part of a manipulative group are strongly emphasized by Janja Lalich, a recent PhD and a former member of an authoritarian and regimented Marxist cult. The author draws upon her own past experiences in arranging for the misleading of outside observers and constructing facades for their bemusement. She warns observers what to watch out for.

The second section of our volume is concerned with brainwashing. The literature on cultic ‘brainwashing’ is lengthy, acrimonious, and polarized (Anthony 1996; Anthony and Robbins 1994; Barker 1984; Bromley and Richardson 1983; Introvigne 1998; Katchen 1997; Lifton 1991; Martin et al. 1998; Melton forthcoming; Ofshe 1992; Ofshe and Singer 1986; Richardson 1998; Zablocki 1998; Zimbardo and Anderson 1993). The basic conceptual and evidentiary issues are discussed from three different perspectives by Benjamin Zablocki, Dick Anthony, and David Bromley.

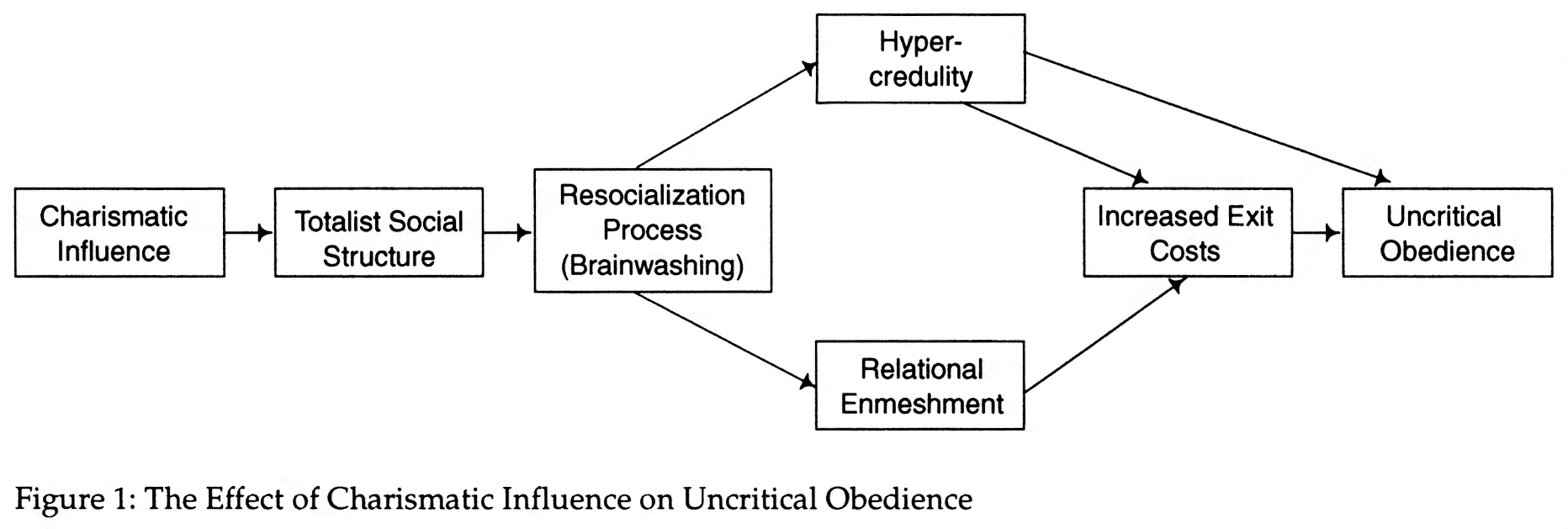

In chapter 5, Zablocki returns to the original mid-century definition in developing a concept of brainwashing that is less polarized, less partisan, less ‘mystical’ and more scientific than those that became popular during the cult wars of the 1980s. Zablocki’s chapter seeks to demonstrate the epistemological validity of the concept and the empirical evidence for its existence in cult settings. He sees brainwashing as an objectively defined social influence mechanism, useful for understanding the dynamics of religious movements, not for making value judgments about them. He argues that brainwashing is not about free will versus determinism, but rather about how socialization places constraints on the willingness of individuals to make choices without regard for the consequences of social disapproval. In this context, he sees brainwashing as nothing more than a highly intense form of ideological socialization.

In chapter 6, Dick Anthony sharply criticizes this approach, as embodied in earlier books and papers by Zablocki. He develops a concept, which he refers to as ‘tactical ambiguity,’ to explain how brainwashing theorists have attempted to avoid empirical tests of their arguments by continually shifting the grounds of their key assumptions. Using this concept he argues that, disguised behind a veneer of pseudo-scientific jargon, Zablocki has essentially resurrected the old thoroughly discredited United States Central Intelligence Agency model of brainwashing from the 1950s. This CIA model argued that it was possible to perfect a formula that would rapidly and reliably allow the agency to remold ideologically any targeted subject against his or her will, in order to become an effective secret agent of the United States government. Anthony further argues that part of Zablocki’s theory can be dismissed as double-talk, and that the rest is unscientific dogma (disguising Zablocki’s personal scepticism about the authenticity of innovative religion) because it is based on the intrinsically untestable notion that any subject’s free will can be overwhelmed by irresistible external psychological forces. Anthony argues that the term brainwashing has such sensationalist connotations that its use prejudices any scientific discussion of patterns of commitment in religious movements.

In chapter 7, David Bromley argues that the whole controversy over cultic brainwashing is essentially ideological and political – not scientific. From Bromley’s perspective, competing ‘narratives’ in this area are not really susceptible to a definitive empirical resolution. Bromley aims at neutrality between conflicting ‘ideological’ perspectives. His relativistic approach is not directly critical of either Zablocki’s or Anthony’s position. However, it undercuts the position of the more absolutist crusaders against the utility of using the brainwashing concept as a tool for understanding cults, as well as the position of those who see brainwashing as the single key for understanding these movements.

Section 2 has a second subsection which revolves around evidence advanced by sociologist Stephen Kent that the Church of Scientology in the recent past, and the Children of God (now called The Family) in the 1970s, employed rigorous programs for resocializing deviant members, which, he argues, not only qualify as brainwashing but contain as well an element of physical coercion or captivity (chapter 8). Kent’s notion of brainwashing is convergent with Zablocki’s treatment in terms of seeing brainwashing not so much as a way of initially converting or recruiting devotees but as an intensive (and costly) method of sustaining commitment and orthodoxy among existing high-level converts in danger of straying into heterodoxy, dissent, or defection.

Kent’s argument is subjected here to a methodological critique by sociologist Lome Dawson (chapter 9). Dawson argues that Kent’s analysis is one-sided, since it uses ex-member accounts as a source of data but does not attempt to balance their perspective by obtaining countervailing accounts from the cults themselves. Dawson maintains that Kent fails to demonstrate that his explanation of the data is more convincing than a number of other explanations that can be found in the literature on new religious movements.

The Kent-Dawson dialogue departs from our rule that authors would not be given additional space in the book to reply to other authors with whom they might disagree. We made an exception here, allowing Kent to write a brief rejoinder to Dawson’s critique (chapter 10). The reason for this exception is that, at the time we commissioned Kent’s chapter, we were not aware that Dawson had written a critique of Kent’s paper that he wished to publish in our book. By the time we received Dawson’s critique, Kent had already submitted his chapter, unaware that it might be followed by a critique. In courtesy to Kent, therefore, we asked his permission to include the Dawson critique, and Kent agreed providing that he be allowed to append a brief rejoinder. Since both authors were happy with this arrangement, we agreed to make an exception in this one case.

The final section of our volume is structured somewhat differently from the preceding two sections. Instead of sets of paired or clearly interrelated essays, section 3 consists of three papers, each of which explores a separate topic relevant to questions of public policy with regard to cults. Since it was not possible, in a volume of this size, to cover all the relevant public policy issues, we devote a chapter to each of three such issues: the problems of children growing up in cults, cultic pressures on scholars to suppress evidence, and problems raised when new religious movements become violent in their relations with society.

The treatment and experiences of children brought up in cults has attracted significant critical attention and is now producing increasing scholarly research (Boyle 1999; Palmer and Hardman 1999). Sociologist Amy Siskind (1994) grew up in a radical, communal therapeutic movement. Her present contribution (chapter 11) seeks to conceptualize totalistic child-rearing systems and to describe and compare five communal groups in this area. Each group featured an ‘inspired’ charismatic leader/theoretician. In each group parents were to some degree displaced as caretakers and disciplinarians of their children by movement leaders. In two of the groups, patterns of child rearing clearly shifted significantly over time and were influenced by several key variables. Siskind argues that children growing up in regimented totalistic groups may be susceptible to certain psychological or developmental problems and will probably face difficult problems of adjustment if they later leave the group. She affirms that child rearing in totalist groups should be investigated objectively without preconceptions.

Sociologist Julius Rubin has studied and developed a critical perspective on the communal Bruderhof sect. His views and expressions are strongly resented by the movement, which, in Rubin’s view, does not tolerate criticism. The group’s retaliatory tactics appear to Rubin to embody the ability of some manipulative cults to use the law courts to intimidate or punish ‘enemies’ and thus endeavor to suppress criticism and to encourage what seems to him arguably a form of implicit censorship. As Rubin reports (chapter 12), what is particularly dangerous about this practice is the ability and willingness of some of the wealthier cults to litigate against critical scholars even in cases they cannot win, knowing that this tactic may very well intimidate both authors and academic publishing houses without deep pockets.

During the period of the millennium, increasing scholarly focus is being directed to catastrophic outbreaks of collective homicide/suicide associated with totalist cults such as the People’s Temple, the Branch Davidians, The Solar Temple, Aum Shinrikyo, and Heaven’s Gate. There is concern over the volatility of various millennialist movements as well as their persecution (Bromley and Melton forthcoming; Maaga 1999; Robbins and Palmer 1997; Wessinger 2000; Wright 1995, 1999; Young 1990). Much of this growing literature revolves around a duality in which intrinsic or endogenous sources of group volatility such as apocalyptic worldviews, charismatic leadership, totalism, and ‘mind control’ are played off against extrinsic or exogenous sources related to external opposition, persecution, and the rash and blundering provocations of hostile officials.

Jeffrey Kaplan’s earlier study of Christian identity, ‘Nordic’ neopaganism, and other militant millennialist movements. Radical Religion in America (Kaplan 1997) inclined somewhat towards the relational or extrinsic perspective and emphasized the dynamic whereby negative stereotypes of controversial movements, which are disseminated by hostile watchdog groups, tend to eventually become self-fulfilling prophecies. In his present contribution (chapter 13), Kaplan presents an overview of millenarian violence in American history with a particular focus on Christian identity paramilitarists, extreme antiabortion militants, nineteenth-century violence employed by and against the early Mormons, violence arising within a youthful Satanism subculture, and the violence of cults such as the Branch Davidians led by David Koresh and UFO movements such as Heaven’s Gate. With regard to cult-related violence, Kaplan rejects the extreme popular scenario of members ‘going unquestioning to their deaths for a charismatic leader,’ as well as the apologetic ‘counter-scenario … that if only the group had been left entirely to its own devices, all would have been well.’ Simplistic, polarized stereotypes of lethal cult episodes are misleading, in part because, as Kaplan notes, there are salient differences among several recent situations in which cults have been implicated in large-scale violence. Extreme violence erupts in only a small percentage of millenarian groups; moreover, sensational cult episodes such as Jonestown, Waco, or Heaven’s Gate account for only a fraction of the violence related to some form of millenarianism. Yet our understanding of such episodes ‘remains at best incomplete.’

Conclusions

We are under no illusion that the chapters in this book will serve to completely dispel misunderstanding of cults. Nor do we seek to disguise the many serious and acrimonious disagreements that still sharply divide scholars working in this field. After decades of polarization, it is an important first step that these authors have been willing to appear side by side in the same book. In the future we would encourage them to continue to debate these ideas in other media.

We are optimistic that the dialogue begun in these pages will have the kind of momentum that will weaken the rigid ‘thought communities’ that have polarized this field of study in the past. Somewhat more cautiously, we are hopeful that this weakening of the two extreme positions will lead to the growth and vitality of a flexible and open-minded, moderate scholarly cluster.

Notes

1 For purposes of this introductory essay we, the editors, will use the term ‘cult’ to denote a controversial or esoteric social movement which is likely in most cases to elicit a label such as ‘alternative religion,’ or ‘new religious movement.’ Such groups generally tend to be small, at least in comparison with large churches, and are often aberrant in beliefs or practices. They are sometimes very close-knit and regimented (‘totalist’) and manifest authoritarian, charismatic leadership. They may be strongly stigmatized. Although the term cult has become somewhat politicized and has taken on definite negative connotations, we do not intend to employ this term in a manner which settles contested issues by definition (i.e., we do not consider violence, ‘brainwashing,’ or criminality to be automatic or necessary attributes of cults). We also do not imply that all cults will appear to all observers to be specifically ‘religious.’ The term has sometimes been applied to groups which do not claim religious status, such as Transcendental Meditation, or which have a contested religious status, such as the Church of Scientology. Some commentators have referred to ‘therapy cults’ or ‘political cults.’ However, most well-known, controversial cults such as the Unification Church (Moonies), Hare Krishna, The Family (formerly The Children of God), the Branch Davidians, or Heaven’s Gate tend to be distinctly religious or at least supernaturalist. Our neutral use of the term cult precludes the view that cults, being pernicious, cannot be authentic religions.

2 As co-editors of this volume, we have not been and are not now entirely neutral or non-partisan in conflicted discourse over cults. Professor Zablocki is sympathetic to organizations concerned with abuses perpetuated by authoritarian groups employing manipulative indoctrination. Robbins has long been associated with avowed defenders of religious liberty and the rights of religious minorities. We thus remain divided over a number of crucial issues. But we are united in deploring the partisan excesses of past discourse, and in our desire to encourage depolarization and the development of a ‘moderate’ agenda among scholars concerned with controversial religious movements.

3 Although we speak of two extremes, we are mindful that the misunderstanding of cults is made even more convoluted by the fact that voices in the debate also include representatives of institutionalized religions. These are also polarized, but in terms of very different issues and with quite different agendas. Matters of doctrine (and possible heresy) are important to some of those within what is known as the ‘counter-cult’ movement, to distinguish it from the more secular ‘anticult’ movement. But other representatives of organized religion are energized by the felt need to defend even the most offensive of the new religions out of concern with the domino effect, once religions come to be suppressed. This book deals only tangentially with the very different set of issues raised about cults by organized religions. But their influence is impossible to ignore, even by secular scholars, if only because of the alliances to these groups that influence public stands on cult policy.

4 The term ‘cult apologist’ is in fact frequently employed by critics of cults to devalue scholars who are deemed to be too sympathetic towards or tolerant of objectionable groups. However, the term ‘cult basher’ is somewhat less ubiquitous. Scholars who disdain the views of strong critics of cults are usually more likely to refer to ‘anticultists’ or the ‘anticult movement.’ Deceptively mild, these terms can actually convey a significant stigma in an academic context. There is a clear implication that anticultists are movement activists, crusaders, and moral entrepreneurs first, and only secondly, if at all, are they scholars and social analysts; this is in contrast to putatively objective scholars who labor to dispel the myths and stereotypes disseminated by anticultists. However, since the term cult basher has an appealing surface equivalence to the more ubiquitous cult apologist, we will continue to use cult basher to denote one pole of the controversial discourse on cults.

5 Robbins’s chapter in this volume discusses the way in which growing litigation in this area and the interaction of the ‘cult of expertise,’ with the underlying adversarial system for resolving questions of law and policy in the United States operates to polarize conflicts involving cults.

6 This is a difficult issue, and we will pause before adopting an absolutist position. Some kinds of information may be accessible only to an observer who is trusted as an ‘insider’ (i.e., full participant). This may be the case not only with respect to ‘secret’ arrangements and practices, but also with regard to the thought patterns, verbal styles, and demeanor of devotees, which may vary according to whether they believe they are relating to insiders or outsiders (Balch 1980). What does seem objectionable is when an observer has used deception to gain access to a group, but with the hidden purpose of hurting or embarrassing the group, i.e., what might be termed the ‘Linda Tripp mode of participant observation.’ But must ‘undercover’ researchers always be obliged subsequently to be supportive of the (sometimes seriously flawed or objectionable) groups they have investigated?

7 We do not wish to appear unduly naive or as ivory tower isolationists. We realize that policy concerns often drive social research. The study of particular ‘social problems’ has often been constituted by social movements which have addressed or even constructed social issues. Thus a current boom in research on aspects of memory has responded in part to controversies over recovered memory syndrome and false memory syndrome. But this example may also illustrate the pitfalls of researchers becoming too partisan and committed to policy orientations. A prominent participant in recovered (vs. implanted) memory controversies has recently warned against researchers becoming too beholden to a priori commitments and thus tending to surrender the residual operational neutrality which sustains the authenticity of the research process and the credibility of emergent findings (Loftus and Ketcham 1994).

8 Some of these issues were raised earlier in the 1983 symposium. Scholarship and Sponsorship. The centerpiece of the symposium was a somewhat accusatory essay by the eminent sociologist Irving Horowitz (1983) who called for ‘neutral’ non-religious funding in the sociology of religion, particularly with respect to controversial movements. The divisive impact of Horowitz’s critique may have been muted because Horowitz was neither a scholar specializing in religion, a member of an ‘anticult’ organization, or a supporter of conceptualization of commitment-building within cults in terms of ‘brainwashing.’ The issue of partisanship and objectivity is closely related to the substantive scholarly conflict over brainwashing because allegations of ‘procult’ and apologetic bias are employed to explain why brainwashing notions are so intensely resisted by professional students of religion (Allen 1998; Zablocki 1997,1998).

References

Allen, Charlotte. 1998. ‘Brainwashed: Scholars of Religion Accuse Each Other of Bad Faith.’ Lingua Franca (December/January): 26-37.