Chapter 5

Two days later, Marilyn and I were back in Montreal, facing the hardest task that either of us could recall: telling Benji’s parents of their son’s predicament. During our two weeks in California, the Millers had phoned several of our friends seeking information about their long-absent son. No one had told them about our own involvement, in hope that Marilyn and I would return with Benji—but now we knew that the time had come. The day after our return, we invited the Millers to Lenny and Janet’s home to fill them in.

Libby Miller, Benji’s mother, was an open, talkative woman—by most standards, a somewhat typically suburban mother. Tall and attractive, with tinted blonde hair and a pale complexion, she worked part-time in a camping gear store and filled her spare time doing volunteer work in her community. But her principle interest was the well-being of her three children: Janice, a gangly teenager, preparing to enter college; Debbie, an aspiring pianist, practising music therapy in Europe; and Benji—the eldest and most independent, who she never stopped hoping would settle down with a wife and career.

Charles Miller was a warm, good humoured man, as predictable a father as Libby was a mother. An executive in the fashion industry, he boasted a small clothing line with the Miller name; but to friends and family, he was simply “Charlie”—a paunchy, balding man with an elfin smile, a fast wit and an unlimited supply of one-line jokes.

“How does the labor leader begin a bedroom story?” he asked us, seconds after entering Janet and Lenny’s home. We hardly had time to catch our breath before the reply:

“Once upon a time-and-a-half.”

The pair arrived exactly on time, he carefully attired in a suit and tie; she in a smart white dress; as we had predicted, they brought along a freshly-purchased coffee cake, which remained untouched throughout the evening’s talk.

Gently but straightforwardly, we laid out our tale, from Mike’s disappearance and return, through my own experience at Boonville. Though the details of our story were clearly a shock, their son’s dilemma was not a complete surprise. Since Benji’s departure, the Millers too had had their share of strange letters, dwindling in numbers, and abrupt phone calls with no details of the “Project”.

“Everything was so secretive and mysterious,” recalled Mrs. Miller. “Benji kept saying it was such a great place…but he couldn’t tell us one word about it! We didn’t know what it was he was involved in, but both of us had that feeling that it wasn’t very good.”

Overall, it was the grimmest evening I ever spent, watching the two parents exchange pained glances and struggle to hold back tears. When we finished our story, each of them had a rush of questions. Mrs. Miller’s concerns were fairly motherly: how did Benji look? What was he wearing, how were his weight and complexion? Was there any possibility that he might be happy?

For Mr. Miller, it was nuts and bolts: what were the legal options? Who was behind the Moon organization? And most importantly—what were the chances of getting Benji out?

We answered their questions as candidly as possible—though I concealed one bit of information from them, and everyone else: I had little hope of seeing Benji again. My own stay in Boonville had badly demoralized me and left me in awe of the Moonie techniques. I had had several nightmares about Boonville since leaving the camp; now the whole trip seemed like a terrible nightmare, and I was chilled at the prospect of returning to San Francisco again.

Well after 2 a.m., we accompanied the Millers to the door of Lenny’s flat, where they smiled graciously and thanked us for our help. They descended the stairs with remarkable poise, but watching them through the window, we could see them collapse in each other’s arms, when they reached their car.

Over the following two days, we spoke with the Millers often, and gave them our files on Sun Myung Moon. They devoured our information and increased its scope with phone calls of their own—to San Francisco lawyers and police and to anti-Moon forces in a dozen states. Moved by their efforts, my own spirits began to rise, and I went back to the telephone to look into the committee headed by Rep. Donald Fraser that was already investigating Moon’s political ties. Soon, with a few press contacts and a little luck, I came up with a Washington connection who promised me plenty of new information in the days to come.

But even before he returned my call, the Millers had learned more than they cared to know about Rev. Moon. Within three days of our return, they put forward their feelings, and everyone was in accord: we had to see Benji alone for long enough to talk to him. Since our own visit had been utterly in vain, and legal recourse was impossible, there was only one thing left for us to do. We would have to kidnap Benji.

“What else can we do?” asked a distraught Mrs. Miller. “Maybe we’re acting like crazy parents…but I don’t want to take the chance. If it’s still our Benji, I think he’ll understand.”

We needed to lure Benji out, and fortunately, we had some bait: Benji’s sister Debbie was visiting from Europe. A diligent, serious young woman of 26, Debbie was as different from her carefree brother as one could imagine, yet more surprised at his disappearance than anyone else. Benji was her “big brother”—a strong-willed, even-tempered, independent person whom she had always admired.

“I could imagine this happening to dozens of people I’ve met,” she told us privately, “but not to him…not Benji! We’ve got to find a way to talk to him.”

Several days after our initial encounter with her parents, Debbie Miller sat alone in the family basement and telephoned her brother at Washington House. According to the woman who answered, Benji was “away”, but would call her back upon his return. The next day he did—his voice impassive, but his words indicating that he was pleased to hear his sister had returned.

According to plan, Debbie told him she would be visiting Vancouver to see an old friend, and she asked Benji to meet her there. He declined quickly, as it was “impossible” for him to leave California—but after a momentary pause, he invited Debbie to visit him. She asked for time to think it over, and Benji promised to call back the next day.

By the time his return call came, more than two days later, we had devised our plan. At first, Benji’s invitation had seemed just the opening we needed, but on closer inspection it was a bigger risk than we could afford to take. While the old Benji would genuinely have wanted to see his sister, Benji the Moonie might have other motives: more than likely he would see Debbie as a potential Moonie, and whisk her up to Boonville at the very first chance.

No one was prepared to see Debbie go alone; the last thing the Millers needed was a second child to extricate from the cult. We had to find a way to get Debbie to California, without the possibility of a Boonville trip—and soon, a solution became clear.

When Benji’s second call came, Debbie told him that Mrs. Miller was anxious to join her for the trip. But to keep the pot sweet, she assured him that their mother would stay for only three days, while Debbie would remain another week, alone. The possibility of luring Debbie up to Boonville once her mother had left, was obvious; after a brief silence, Benji jumped at the bait. When Debbie hung up several minutes later, Benji had agreed to pick up both sister and mother at San Francisco airport in four days time.

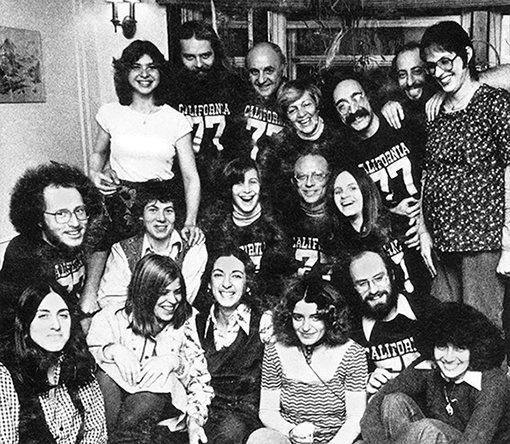

That night we gathered at the Miller’s home to assemble a kidnap team, though it soon became apparent that our resources were lean. A reluctant volunteer, I was nonetheless everyone’s first draft choice, as Marilyn could not go and no one else had been to San Francisco. Lenny, an old friend of Benji, agreed to accompany me, and Gary, a film teacher, and Simon, a union representative, hesitantly volunteered to round out our troupe.

As kidnappers went, we were a sorry collection: four balding pacifists, all pushing 30, with nary a fist fight between us since our public school days. Even if we did have the brains to plot a decent kidnapping, somebody else would have to provide the brawn. Our only hope was that we would find lots of help among our many friends in San Francisco.

Benji’s father, Charlie, would also join us for the trip—as we would need his assistance once we got our hands on Benji. But that moment seemed far off indeed; with little more than a vague idea of what we would do once we arrived, our strange crew made its reservations to fly to San Francisco and kidnap Benji.

As we left the Miller’s home that final evening and went our separate ways, all of us were nervous and unsure about the coming days’ venture. But by the following morning we were even more perturbed, for during the night I had received a phone call from my Washington connection, who told me everything that he had learned about the forces behind Moon.

When our plane flew off into the western sky the next afternoon, we knew a great deal more about our Korean adversary. His influence was far greater and closer to home than any of us had imagined.

Chapter 6

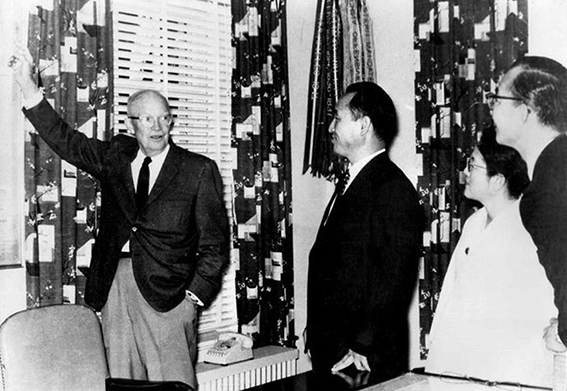

On a June day in 1965, a limousine pulled into the spacious Gettysburg farm of Dwight D. Eisenhower, retired president of the United States.

Out of the car stepped a delegation sent by Ike’s old friend Yang You Chan, former South Korean ambassador to the U.S.: the group included several young Korean dancers known as the “Little Angels”, accompanied by a rotund man introduced as a Korean minister.

“You are well armed with cameras, I see,” joked the elderly ex-president, as shutters clicked. “And what is the name of your movement?”

“The Unification Church,” clucked the Korean evangelist, as his handsome assistant Bo Hi Pak pulled out a glossy biography of Moon, including photos of a recent 124-couple wedding he had conducted. Eisenhower’s eyes grew “round”, according to a Unification Church magazine describing the incident.

▲ Former president Eisenhower with Sun Myung Moon, Won-bok Choi and Bo Hi Pak.

“Never saw anything quite like this before,” said the surprised ex-president, who spent the next 45 minutes amiably chatting with his guests before the limousine disappeared down the road again. For Ike, the meeting was just another interruption in a pleasant Pennsylvania day; but for the man in the car—Sun Myung Moon—it was a crucial encounter; the first tiny wedge in a crack that would eventually open a broad passageway to some of the most powerful people in the United States.

Soon after the meeting, Eisenhower agreed to become the “honorary president” of the Korean Cultural Freedom Foundation (KCFF), supposedly an organization to fight communism and promote Korean-American cultural ties: in reality, a front group for the Unification Church.

Using this key endorsement from Ike, Bo Hi Pak soon milked similar endorsements from former president Harry Truman, dozens of senators and congressmen including Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, and eventually a Who’s Who of American personalities such as Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Ed Sullivan.

These sponsors in turn opened the taps to some million dollars a year in KCFF contributions from 140,000 Americans trying to fight the “Red menace”—a flow of money that would remain undammed until 1975, when the group’s links to Moon finally became known.

But by that time, the cloak over the KCFF was expendable; Rev. Sun Myung Moon had many more irons in the fire…

Slightly more than a year after our kidnap team left Montreal, the U.S. Congressional Committee headed by then Rep. Donald Fraser would conclude its lengthy investigation of Moon’s political empire. Fraser would find that Moon had been one of the key components in a vast attempt by the South Korean Government to influence U.S. domestic and foreign policy, and that Moon in turn had used both the Korean Government and an astonishing number of prominent American personalities to further his own goal— which was no less than to “get hold of the whole world”.

The committee’s findings would seem an extraordinary list of accomplishments for a fringe cult whose leader had long been the object of ridicule. But they would come as no surprise to us—only confirming publicly what we had learned a year earlier from our friends in San Francisco and from our Washington connection: that paralleling Moon’s complex financial organization, is an even more complex and murky political empire, the full extent of which may never be known. Some of the components of that political empire uncovered by the Fraser Committee are outlined in the following pages.

Korean Cultural Freedom Foundation (KCFF)

Once Eisenhower and Truman were persuaded to become honorary presidents, fourteen generals, eight admirals and an army of American personalities clambered onto the KCFF’s “advisory board”.

Their endorsements enabled the KCFF to churn out PR material befitting Bicentennial Day, asking for money to “fight communism” and help save “starving Korean children”. Thousands of prominent Americans were taken in, among them George Meany, Jack Nicklaus, Johnny Unitas and Rep. Carl Albert. The owners of Reader’s Digest alone gave the KCFF half a million dollars.

The only critical voice came from the U.S. embassy in Korea, which continually warned that the KCFF was a front group for “unsavory people”—but the U.S. Government took no action.

In 1976 a New York State agency audited one of the KCFF’s charitable ventures, The Childrens’ Relief Fund, and found that only two per cent of the $1.2 million collected that year had gone to hungry children. They banned the KCFF from soliciting in New York, and slowly the national spotlight focused on the organization.

By 1978, the KCFF’s blood links with Moon and the Unification Church were completely known and its profits and power greatly reduced. However, Bo Hi Pak still operates the KCFF and continues to claim it has “no connection to Moon”.

The KCFF also gave birth to other projects, notably the “Little Angels”—a colorful Korean childrens’ dance troupe that did wonders for Moon’s prestige. Moon conceived the group in 1962, then turned it over to the KCFF which soon had support from the Korean Government.

Moon hoped the group would someday spread his influence into the “palaces of kings and queens”, and it almost did. The Little Angels had a private audience with Queen Elizabeth in Buckingham Palace, and were the first cultural group to appear before the United Nations. They played with stars like Sammy Davis Jr. and Liberace, in concert halls from Carnegie Hall to Africa, and recorded an album with MGM.

The concerts provided Moon the opportunity to mingle and have his picture taken with politicians and diplomats. These photos were added to his growing stock of PR material to further enhance his image as a world-respected figure with powerful friends.

The third major KCFF project, a brainchild of Bo Hi Pak, was Radio [of] Free Asia (ROFA)—a radio outlet intended to broadcast to the “suffering millions” behind the bamboo curtain. This venture also attracted millions of dollars of private American money, until 1975, when its close links with the Korean Government and Moon became public. ROFA was discontinued soon afterwards.

Freedom Leadership Foundation (FLF)

The FLF is the Church’s chief political arm in the U.S. It is registered as a non-profit educational organization, intended to “develop leadership” in the “struggle against communism”.

When it was founded in the late sixties, it stirred protest among some early Church members who came from left-wing backgrounds. They were told that it was a religious command to begin political work in the United States.

“Thereafter, members’ objections to political activity was considered infidelity to Master and was like being disobedient to God,” says Alan Tate Wood [Allen Tate Wood], President of the FLF in 1970, and one of the topmost defectors from Moon’s Church.

“North Korea’s Strategy to Make New War…belligerent, warmongering tactics…” blared slick propaganda leaflets handed out by the FLF. “The U.S. must not fail…to defend South Korea against communist aggression.”

This anti-communist stand not only ingratiated Moon with the South Korean government but broadened his contacts with prominent Americans. FLF publications at the time contained photos of Moon meeting Ike, Humphrey, Thurmond, Kennedy, Nixon and other distinguished Americans.

FLF chapters were also set up in 40 countries, under an international Moon anti-communist front known as “Victory Against [Over] Communism” (VOC). In Japan Moonies campaigned for right-wing candidates during elections, in Vietnam they provided medical units, and in South Korea they set up the World Freedom Institute, a still-functioning anti-communist indoctrination center to which Korean civil servants and army officers are sent annually for an overview of Communism.

But FLF President Neil Salonen, a top Moon spokesman, maintains that their anti-communist work and support of South Korea is not a function of political beliefs but rather of “spiritual, religious feelings”.

“We don’t lobby,” says Salonen. “We educate.”

One of the FLF’s chief educational tools was the Washington lobby team—some twenty attractive, well groomed Moonie women who distributed tea, flowers and friendship at Capitol Hill until 1977.

Operating out of an old manor several blocks from the Capitol, the teams lobbied congressional staff on issues of concern to Moon, and tried to form personal relationships with staff members on any pretext they could.

“They were sweet girls, they put you at ease. They sent you flowers,” New York State Senator Israel Ruiz said of his encounter with them during Moon’s 1976 God Bless America festival. “They were the most terrific propagandists I’ve ever encountered.”

Moon’s speeches to his members hardly concealed the purpose of the lobby: “Master needs many good-looking girls—three hundred. He will assign three girls to each senator…if our girls are superior to the senator in many ways, then the senators will just be taken by our members.

“If we find among the senators and congressmen no one really usable for our purpose, we can make senators and congressmen of our members. This is our dream—our project—but shut your mouth tight and have hope and go on to realize it. We must have an automatic theocracy to rule the world.”

The team rented a special suite at the Washington Hilton at which they entertained receptive congressmen and staff. The girls were well-trained, and encouraged to use deceptive tactics, justifying them by the Moonie motto: “Be as wise as serpents and as innocent as doves.”

“The implication was to be persistent and cunning —anything to make him like you so he’d become a friend and ally,” recalls one former member of the lobby team. “It was very effective.”

The Fraser Committee concluded that it was hard to say how successful the team was in getting to members of Congress, but some of their achievements are worth noting. At least two members of the team, Sherry Westerledge and Susan Bergman, were employed on the staff of congressmen until 1979, though they continued to live at the Church headquarters and turn over their salary.

Miss Bergman, who worked for Rep. Doug Hammerschmidt, won attention in 1976 for her curious relationship with the former Speaker of the House, Carl Albert. The pretty, hazel-eyed Miss Bergman would bring Albert flowers each morning, then brew him ginseng tea in his office and later accompany him around Capitol Hill. Albert came under criticism for his actions but he insisted that Miss Bergman was “just a nice girl, a very nice girl, a Jewish girl from New York. She got all hepped up on Jesus and she just wants to share it. I think that’s a nice thing. I think she wants to convert me.”

As a result of the lobby team’s efforts, Moon himself was able to penetrate Capitol Hill on several occasions, notably for a prayer meeting in his honor held in the House Caucus Room by Congressmen Bill Chappell and Richard Ichord. Moon arrived for the affair in a resplendent black Lincoln and was trailed by bodyguards down the congressional halls to the Caucus Room. According to Time Magazine, Rep. Ichord then said he was “profoundly impressed” with the church group and “broadly compared the millionaire clergyman to Moses, John the Baptist and Jesus”.

The lobby team has not been active in Washington since the end of 1977, but many of its members now belong to PR teams that travel the country explaining the Church and its principles to local politicians, university students and businessmen.

Operation Watergate

The best known of the Church’s political activities was its effort to save Nixon during Watergate, a campaign which eventually gained Moon entry to the Oval Office.

Dubbed “Project Archangel Nixon”, the lobby began in November 1973 with full-page newspaper ads in 21 cities calling on readers to “Forgive, Love, Unite…God has chosen Richard Nixon…We must love the President of the United States”. These ads were followed by a forty-day Prayer and Fast Vigil on the steps of the Capitol Hill and intense lobbying by the Washington team, which secured the signatures of 28 congressmen and 4 senators to endorse their fast. One congressman read an “inspirational appeal” by Moon into the record.

Subsequently, Moon’s Watergate Committee was called by President Nixon’s secretary and invited to attend the annual White House Christmas Tree Lighting Ceremony December 14th. Twelve hundred Moonies showed up, demonstrating for the beleaguered president in a well-rehearsed display.

Transcripts of Church documents obtained by the Fraser Committee record Church leaders drilling members on how to behave. “Small, intimate personal things can make a large impact…On camera, medium prayer looks very good. Very strong prayer doesn’t. It looks strange…don’t clench your fists when you are singing.”

That night the Moonies returned for a candlelight vigil during which Tricia Nixon and husband Edward mingled with the crowd and offered their thanks. Similar demonstrations were held by Moonies in Japan, Germany, Italy, England and other U.S. cities.

Soon after, Moon was invited by the president’s office to the annual Prayer Breakfast for religious leaders on February 1, 1974. Later that day he met privately with Nixon for thirty minutes in the Oval Office, where he reportedly hugged the President and prayed fervently over him in Korean. A few months later, Moon told his followers:

“If this dying person, Nixon, is revived, then Reverend Moon’s name will be more popular and famous, right?”

An interesting footnote to the Watergate Project is the possibility that lobbyists were also gathering information on individual congressmen. Each Moonie lobbyist was assigned 23 congressmen and told to keep an index card on each, citing “every time the congressman saw you, spoke to you…including the time, location and circumstance. Describe your interaction in detail.”

Why was the information gathered?

“It was all in the interest of the Mission—with a capital M,” a former member of the lobby team told me. “But I had no idea what that Mission was…I just followed the orders of the higher-ups.”

International Conference for the Unity of the Sciences (ICUS)

Moon’s major thrust at the scientific community, ICUS is an annual event that gathers hundreds of academics from around the world to discuss “The Search for Absolute Values”.

The conference is a ritzy affair: all travel, food and lodging costs are picked up by Moon, and the bill usually reaches $500,000. Some guests refuse to come when they learn the conference is sponsored by Moon, but many others aren’t bothered in the least.

In 1978, the affair was held in the days following the People’s Temple suicide in Guyana; nonetheless, ninety per cent of those invited showed up, including four Nobel Prize laureates and other notables like Paolo Soleri, Karl Pribham and Kasim Gulek, former prime minister of Turkey.

Outside the hotel, protesters carried placards asking “Scientists! Where are your ethics? Where are your values?”

Inside, debate focused on everything from “Health Problems in West Africa” to “Etiologic and Immunologic Aspects in Nasopharyngeal Cancer”. The most striking workshop was one entitled “Death and Suicide in Contemporary Thought”—a 2-1/2 hour session during which, astonishingly, the days-old tragedy in Guyana was never mentioned, despite newspapers littering the conference floor announcing that the death toll had climbed to 775. Instead, scientists mulled over debate on “romantic suicides” by Sylvia Plath and Plato’s Socrates: the main paper, by author Joyce Carole Oates, was on “The Art of Suicide”.

▲ Nobel Laureate Eugene Wigner and Moon

Most participants, like Nobel physics laureate Eugene Wigner, termed it “irrelevant” that the conference was sponsored by Moon. Others were more lavish in their remarks: MIT sociologist Daniel Lerner praised the Moonies as “among the greatest young people we have today”.

Several hundred Moonies were brought to the conference, in buses labelled “Aboji Monsei” (Victory for Father). Looking like they shared the same tailor and barber, the well-groomed youngsters sat watching the affair with a curious but impressed expression while higher-ups mingled with the scientists. After all, that’s what the conference was for. As Master Speaks explains:

“If we invite them (the scientists) on the pretext of giving these lectures they will be touched by the students, then they will want the students in their university to go through this type of training. Before long, without money we will influence the whole of the United States by influencing the intellectuals first… We will surely influence the policies of the whole world, in the near future.”

The Fraser Committee characterized ICUS as part of Moon’s overall strategy of controlling major institutions around the world. Moon also speaks of setting up a Unified Economists Conference, a World Politicians Conference and a World Media Conference.

He has also promised to establish a “prize system” more prestigious than the Nobel Prize, and has pledged to build his own university. Land in New York has already been purchased for it.

Korean, KCIA Connection

Who, if anyone, is behind Rev. Moon? Does he actually believe he is the Messiah, or does he represent larger interests?

Many ex-Moonies I have spoken with are convinced that Moon does indeed believe in his own power as Messiah. Their opinion seems to be supported by Moon’s own personal behavior and by the sheer flamboyance of many of his speeches.

Even Bo Hi Pak, Moon’s right-hand man and liaison with the South Korean Government, seems to be a “true believer”: according to Judy Stanley, Pak registered his own son in Barrytown’s 100-day “training program” on the day he turned sixteen. Many other leaders particularly those in the lower echelons, seem to be thoroughly indoctrinated.

Yet despite their convictions, there is far more to Moon and Pak than religion. The Fraser Committee found them to be at the center of South Korean government schemes to influence the United States.

Don Ranard, former director of the State department’s office of Korean Affairs told me: “Moon and Pak may both be on the strange side, but even if they are…they know exactly what they’re doing. They have friends and influence in all kinds of high places and they represent a lot more than the Unification Church.”

To understand Moon’s political roots, one has to know something of South Korea since 1961, when Park Chung Hee overthrew the constitutional government of that country and installed a military dictatorship.

Propping up the Park regime was the omnipresent KCIA, described by one U.S. State department man as “a state within a state, a shadowy world of…bureaucrats, intellectuals, agents and thugs”.

Established in 1961 with the aid of the American CIA, the KCIA has since earned a reputation as one of the most brutal and repressive security forces in the world. With an estimated force of 50,000 men and women, the KCIA controls all aspects of life in South Korea: nothing is printed or broadcast without their approval; politicians, labor leaders, government officials, clergymen and students are all watched, and sometimes arrested, beaten and killed.

These are the swampy waters from which Moon has emerged intact, well-groomed and very influential; his relationship with South Korean authorities unclear, but evidently good. Consequently, many critics have accused Moon of being a direct agent of the KCIA, a charge which Bo Hi Pak brands as “Trash, total lies, distorted and vicious in nature.”

In its report, the Fraser Committee stopped short of saying that Moon was an agent for the South Korean Government, but it concluded that there was at least a “collaborative relationship” between the two parties. Moon was given freedom of movement and often support for his ventures by the South Korean government; in return he worked consistently in its interests, and sometimes under its direct orders.

In the words of former FLF president Alan Tate Wood [Allen Tate Wood], the goals of the Unification Church and the KCIA in the United States “overlap so thoroughly as to display no difference at all”.

Moon’s relationship with the KCIA began in 1962, when the agency’s first chief, Kim Chong-Pil, met secretly with a small group of North American Moonies at a San Francisco hotel. Two of Pil [should be Kim Chong-Pil]’s top aides were already members of the Unification Church, and, over soft drinks, Pil [Kim Chong-Pil] is reported to have told the American group he would work behind the scenes for the Unification Church in both South Korea and America.

Three years later, while still directing the KCIA, Pil [Kim Chong-Pil] became honorary chairman of the Korean Cultural Freedom Foundation (KCFF), the Church’s first front group in the United States.

According to the Fraser Committee, this cozy relationship between Moon and the Korean authorities continued in the years ahead. The South Korean government sponsored such Moon enterprises as Radio Free Asia and the Little Angels, and gave Bo Hi Pak access to the diplomatic pouch and cable in South Korea’s U.S. Embassy. On one occasion the KCIA hired three Washington secretaries on the direct recommendation of Moon’s FLF.

Moon has also been allowed to hold rallies in South Korea, and on at least one occasion was feted by South Korea’s speaker of the House, who threw a banquet in Moon’s honor.

In exchange, Moon’s Washington lobby team worked to convince U.S. representatives to maintain the 40,000 troops and billions of dollars in aid that the U.S. sends to South Korea. They also staged rallies in support of Park in Korea and in the U.S., one of which the Fraser Report states was specifically ordered by the KCIA.

Moon’s support of South Korea goes further. It is woven right into his Divine Principle, in which he teaches members that Korea is the Holy Motherland, the “second Israel”, and Korean the holy language that everyone in the world will speak some day.

Moonies are encouraged to fight on the “front lines” of the Korean struggle and some members have even pledged to die in battle, disturbing parents who worry that Korea may use American Moonies.

As always, Moon’s own words are hardly reassuring: in 1975 he told a huge rally in South Korea that in the event of another Korean war, Unification Church members “believe it is God’s will to protect their Fatherland to the last, to organize the Unification Crusade Army, and take part in the war as a support force to defend both Korea and the free world”. (My italics.)

Yet Moon’s final vision seems to stretch much further than tiny Korea, which he views as little more than a launching pad for his overall strategy to “conquer and subjugate the world”. In Master Speaks, Moon repeatedly states that he will take control of the world’s institutions and create a “world theocracy” with himself as leader. He even warns of a final, cataclysmic battle in which:

“We should defeat Kim Il Sung (president of North Korea), smash Mao Tse Tung and crush the Soviet Union, in the name of God.”

In the final analysis, Moon may work for South Korea in the short term, and may even be a direct agent of the South Korean government and the KCIA, but his dreams are far grander:

“My life is not so small that I would act as a KCIA agent. My eyes and goal are not just for Korea. America is the goal; the world is my goal and target.”

Japan

One facet of Moon’s political empire was not even touched upon by the Fraser Committee—the Japanese connection which some Moon-watchers believe to be more important than even the link with Korea. Moon’s Japanese Church, the Genri Undo, is an influential movement tied to some of the most powerful ultra-right nationalist forces in Asia.

Moon’s three principal backers in the Orient are Ryoichi Sasagawa, Nobusuke Kishi and Yoshio Kodama—post war billionaires and political forces who share a dream of restoring the Emperor and Japan to their former glory. Some observers believe they are the real power behind Moon.

Sasagawa is the godfather of the Japanese underworld and the founder of the Japanese kamikaze pilot squads. He was imprisoned briefly as a Class A war criminal after the war, then released to become a billionaire political power in Indonesia and Cambodia. He actively supports the Unification Church in Japan, and is described by Bo Hi Pak as a “true humanitarian and patriot”, by Moon as “very close to Master”.

Sasagawa was also at the center of the old China Lobby—a powerful combination of Asian dictators, American right-wing politicians and international businessmen who influenced U.S. policy in the Pacific after World War II. In the 1960’s Sasagawa set up the World Anti-Communist League (WACL), currently the major alliance of right-wing forces in the world. Moon’s Japanese Church is a member of the WACL, and sponsored its 1970 annual conference. Moon claims his Church raised $1.4 million in flower sales and helped finance the “best WACL conference ever”.

The man in charge of promoting that conference was Nobusuke Kishi another active backer of the Japan Unification Church, a former prime minister of Japan, and president of its ruling party. At the 1970 WACL meeting, Kishi organized a grand welcoming banquet for Moon when he arrived in Japan.

According to Bo Hi Pak, both Kishi and Sasagawa help the Unification Church by “encouraging young people through their position as elder statesmen. They open doors, issue statements and attend rallies, and they testify to other important Japanese.”

The third member of this right-wing triumvirate, Yoshio Kodama, has been described by the New York Times as “one of the most powerful men in the Orient”. He recently became notorious for his role in the Lockheed pay-off scandal involving the Japanese government.

Kodama is considered one of the kingpins of Japanese politics, and has had a hand in selecting several prime ministers. He is not an active Moon backer, but acted as an advisor to Kishi and the Moonies during the 1970 WACL meeting. Moon’s links with Kodama, Kishi and Sasagawa have raised speculation that Japan is the source of his early funding; Harpers magazine even speculated that his seed money may have come through the Lockheed pay-offs, raising the possibility that Moon began his growth with American corporate funds.

Moon has at least two other interesting links in Japan. One is with recently defeated prime minister Takeo Fukuda, who attended a banquet in Moon’s honour in 1974, accompanied by two cabinet ministers. When questioned in the Japanese Diet, Fukuda replied: “He (Moon) is a very splendid man, and his philosophy has common parts with my own—namely cooperation and unity. So I was very impressed by him.”

Moon is also close to Japan’s director of the environment, Shintaro Ishihara, who received enormous door-to-door support from the Moonies in the 1976 elections. Shortly after, Ishihara attended a Church dinner and announced: “I received great help from your people…in my election campaign. I had no idea there were such fine young people in present day Japan.”

These links with some of the most powerful people in the Orient make many Moon watchers believe that Moon is more than a puppet for the Korean Government. According to Andrew Ross, a West Coast journalist who broke many of Moon’s Korean connections long before the Fraser Committee. “Moon is right at the center of a constellation of world-wide right-wing forces that is very powerful…and very frightening.”

How powerful is the Church today?

Since the outset of the Fraser Committee, the South Korean Government has gone to great lengths to disassociate itself from Moon and the Church. It has cancelled the passports of the Little Angels ballet troupe and has charged the president of Moon’s ginseng tea company with $6 million in tax evasion. (He escaped to Japan.)

The Church cites these difficulties as proof that it has no links with South Korea, while other critics have said it certainly spells the end of any “special relationship” Moon has enjoyed with the South Korean Government.

The Fraser committee found evidence, however, that as late as 1978 the Church continued to have “significant support” from South Korean authorities. The committee pointed out that in that year a Moon industry was awarded contracts as a chief weapons supplier for the Korean Government. They put particular emphasis on a strange incident that occurred in late 1977: the American weapons firm Colt Industries sent a cable to the South Korean government suggesting an arms deal. Several weeks later Colt officials received a call from Moon’s Tong-Il manufacturing plant. Moon’s representatives then told Colt officials they would work out the deal for South Korea. They said the Korean government was aware of their actions and supported them, but would deny it if it came out in public.

The subcommittee recalled Moon’s professed goals, including the formation of a “Unification Crusade Army”, and concluded its report on this note:

“Under the circumstances, the subcommittee believes it is in the interests of the United States to know what control Moon and his followers have over instruments of war and to what extent they are in a position to influence Korean defence policies.”

The assassination of South Korean president Park in late 1979 throws Moon’s future status in Korea into question. No one can say whether the new government of Choi Kyu-Hah will continue to favor Moon or simply consider him a nuisance. However, it is worth noting that one of the most powerful men in the new government, so powerful that he was considered a leading candidate to become president, is Kim Chong-Pil; the man who met secretly with the Unification Church in San Francisco in 1961 and later became the honorary chairman of the KCFF.

In America too there are strong indications that Moon is far from dead. His financial investments continue to grow rapidly in fishing, film, newspaper and real estate, and his annual science conference continues to attract distinguished academics the world over. In November 1979, the ICUS science conference was held in Los Angeles and drew a full house.

Moon is again living in the United States after several months out of the country during the term of a subpoena by the Fraser Committee, and he is planning a mass wedding of two thousand couples in the United States sometime in 1980. [The mass wedding happened at Madison Square Gardens in July 1982.] He was also hoping to plan a giant “March on Moscow” in 1980—a top secret mission in which troops of Moonies would sweep down on the Russian Olympics in the guise of marching bands, with Divine Principles and bibles concealed in their drums.

Perhaps the most telling example of the Moonies’ still-flourishing power was displayed against the man who has been most effective in exposing them—Rep. Donald Fraser.

In the 1978 primaries, the Moonies campaigned actively against Fraser in his home state of Minnesota. As the Fraser Committee noted, all aspects of the Moon organization were synchronized against him—political, economic and religious. Anti-Fraser brochures were printed up by Moon’s publishing company; documentaries were made of the Fraser hearings by Moon film crews for airing in Korea; articles derogating Fraser and making Bo Hi Pak a martyr were run in News World; and individual Church members campaigned against Fraser in the street.

The results were effective. On October 7, about a month before the release of his committee’s final report, Donald Fraser was narrowly defeated in his bid to become the Democratic candidate for the Senate.

Sun Myung Moon had proved a more powerful opponent than even Fraser could deal with.

❖ Additional information

Gifts of Deceit: Sun Myung Moon, Tongsun Park, and the Korean scandal

by Robert B. Boettcher (1980)

page 324 Five days after the election, Fraser’s house was set on fire. It is not known who was responsible.

page 386 The fire at Congressman Fraser’s home in Washington: Mrs. Fraser and her daughter, Jeanne, left the back door unlocked when they went next door for dinner with friends. Returning home within about thirty minutes to do her schoolwork, Jeanne discovered a fire raging from the bottom of the three-story unencased stairwell. An investigation by the fire department concluded that the fire had been set with solvent poured on the floor, and that had it gone undiscovered for another fifteen minutes, the house could not have been saved.

Village Voice, Nov. 27, 1978 Alexander Cockburn

“Fraser’s enquiry into the Unification Church (with Leo Ryan) demonstrated just how potent these religious political cults can be. Opposition by the Unification Church to [Fraser’s] investigation was signaled by the appearance of the usual coterie of high-priced Washington lawyers. These lawyers protested harassment of the church and violation of constitutional rights. The church sought to block publication of Fraser’s report this fall, and eventually sued him and two investigators for $30 million. More to the point, it despatched lobbyists to Minnesota where the Church played at least a minor role in engineering Fraser’s defeat in the senatorial primary.

During that contest, Fraser’s district office was threatened with bombing and his offices elsewhere in the state were threatened with arson. There is no known connection between the Unification Church and these threats. And no one yet knows who set the fire in Fraser’s Washington townhouse, while his wife and daughter were out for dinner.”

Chapter 7

It took us two days in San Francisco to round up our kidnap team. They were hardly the Magnificent Seven.

Four middle-aged doctors, a Carolina mountain man, a bald textile executive and an Italian private eye made unlikely kidnappers; but time was short and we couldn’t be choosy.

Help had been gathered from rather eclectic sources. Keith, the drinking, thinking mountain man from Loafer’s Glory was still in town and quickly volunteered to help. So did an old friend, Dr. M., an aging Montreal hippie practitioner who had fled Canada for what he termed the “three W’s” of California—warmth, women and weed.

Other San Francisco friends we had counted on dropped out of our plans: one complaining of a nervous stomach, the other a “mild case of terror”. Reluctantly, we agreed to let Benji’s father participate in kidnapping his son from Father Moon.

Next I called Dr. David Leof, a portly Jungian psychiatrist I had consulted when I first returned from Boonville. My tale of the camp’s psychology had so horrified him that he had promised he would “do anything” to help us out. He was as good as his word; the graying psychiatrist suspended an afternoon’s appointments and a lifetime of pacifism to join our crew; as well, he enlisted the help of two polished friends, Dr. G. and Dr. F, prominent San Francisco physicians who normally specialized in kidneys, not kidnaps.

We still needed a seventh man: a private eye to give us advice and tip us off when Benji set foot in the airport. Then Benji’s mother could lure him back to her hotel room, where the rest of us would be waiting to make the snatch.

“This is Mick Mazzoni’s electronic answering service. Speak as long as you want, but keep it short,” snapped the tape-recorded voice of the private eye we hoped to hire.

We had already tried a half dozen other detectives and come to some strange dead ends. One fellow was a brass knuckles type with a voice like a foghorn and an IQ to match; a second spoke to me from the rifle range, his words drowned out by the crack of gunfire. Still another was a pipe-smoking would-be Holmes, who filled our ears with analyses of the “criminal sect type”.

Mazzoni was the first who fitted the bill. He’d been described to us as a “master of a thousand disguises”; as we waited to meet him outside our hotel lobby we scrutinized every passing old lady, convinced it was the chameleon-like detective.

When he finally arrived, and came to our room, his fairly ordinary appearance was a trifle disappointing, though his manner more than compensated. An ex-cop with the demeanor of a drill sergeant, Mazzoni had rugged, almost surly features, and a squared-off beard that I think was real. His army fatigues looked as though they’d been slept in, while his beady eyes constantly scanned the hotel room as though searching for a cache of plastic explosives.

“A good kidnapping is like fixing a flat tire,” Mazzoni explained to us moments after hearing our plan. “There’s no point doing it if you don’t do it right.”

Mazzoni gave us a number of tips, among them to replace our original getaway car with a two-door Cordoba. “The Cordoba”, he said professorially, “has lots of room to stuff a body into the back seat, and the seat belts don’t get in the way.

“It’s a very good car for kidnapping.”

Mazzoni also suggested we plant a “switch car” a couple of miles away, near Candlestick Park, in case our getaway car was spotted. He even told us how to align the cars during the switch (back to front) so that Benji could be transferred with minimum resistance.

Before leaving, Mazzoni insisted on teaching us a bit of judo—transforming our hotel room into a makeshift gym, bodies hurtling through the air and crashing into walls until our neighbors pounded on our door to complain.

“Pssst…take this,” Mazzoni had whispered to me as he left, shoving a thin black tube of tear gas into my reluctant hands.

“If things get rough and you’ve got to get out, throw this and abort the mission.”

Despite Mazzoni’s advice, arranging the caper proved never-ending in its complications as we sallied about the city renting cars, soliciting help and racing back to our hotel to collect our messages. Strange as it was for Lenny, Gary, Simon and me, it was more so for Benji’s father, usually found asleep in the back of the car.

Charlie, as we had come to know him, was a wreck; yet an admirable one, doing his best to cope with the painful situation. When he first paid Mazzoni, he broke into tears, overwhelmed by the macabre nature of the services he was buying. But in the days that followed he adapted remarkably well, keeping up with the frenetic pace, offering invaluable advice and even lounging about the hotel floor with us to eat pizza and drink scotch late into the night.

During the day Charlie burned off his nervous energy telling jokes to anyone who would listen.

“What do you call a honeymoon salad,” he would ask our bewildered hotel waitress. “Come on…ask me what a honeymoon salad is.”

(Silence.)

“Lett-uce alone.”

An hour later he was slumped exhausted in the back seat of the car again, his ever-present tie fluttering in the breeze, as we headed toward our next calamity.

Typical was our renting of the “switch” car. Watching the new car wheel out of the rental docks, Simon bit his lip and whispered to Lenny:

“Geez, what are we gonna do? It’s another blue Cordoba! ”

Lenny paled at the thought of jumping from one blue Cordoba to another.

“You’re not going to believe this,” he stammered to the girl at the counter, “but I can’t stand blue. In fact I’m allergic to it!”

“Me too,” added Simon, as the woman’s eyes darted from one to the other.

“But what’s the difference?” she asked, puzzled. “You’ve only rented it for one day.”

“Yeah, I know,” persisted Lenny. “It’s just that I don’t like blue.”

Down at the far end of the counter, some businessmen were struck by this last remark.

“Ohhh,” they lamented in unison. “That’s too bad. He doesn’t like blooooooo.”

Several minutes later, the sales girl had convinced her disbelieving boss to send down “any colour but blue”, and a shiny green Cordoba came rolling out.

“Green!” shouted Lenny and Simon ecstatically. “We just love green!”

Finding a suitable hotel to stage the snatch proved a major headache, since none of us knew the city. We wanted somewhere out of the way, with one exit that could be easily cut off by a couple of cars and some amateur kidnappers. The search took us from the poshest hotels to sleazy dives where schemes like ours were probably routine.

In one motel we slipped a pass key off the wall of the desk clerk and furtively roamed from room to room seeking the “perfect kidnap site”, only to walk in on a couple in flagrante delicto. In another we were about to rent a second-floor room when Mr. Miller became terrified Benji might leap out the window. We quickly changed our plans.

Mazzoni had suggested we buy a heavy chain and padlock so we could fasten the Moonie vehicle’s steering wheel to a pole after the kidnapping—a gentler method than slashing its tires or smashing the windshield. The mammoth chain trailed suspiciously behind us as we wandered through each hotel seeking a convenient pole.

After sixteen hours and dozens of hotels, we settled on a cozy if chintzy little place just off the freeway. We rented a room, then settled down to see what the traffic situation would be like when Mrs. Miller’s airplane arrived at 5:30 the next day.

At 5 p.m. blondes in sports cars began pulling in and grinding their way up to the rooms. Minutes later men in large cars began to arrive and follow them up the stairs, while police cars completed the strange procession, drifting in and out of the parking lot like a stake-out.

“Good God,” whispered a startled Charlie Miller. “It’s a hooker’s hotel!”

As we turned to flee, we discovered worse: the whole hotel was equipped with hidden cameras, recording our every move since we’d first arrived. We grabbed our padlock and left quickly, remembering to inquire at every further hotel to make sure there were no security arrangements.

Two hours later with night falling and a worn-out Mr. Miller long since asleep, we rented rooms at the Airport Holiday Inn. It was a bit high-profile for our purpose, and it had two entrances; but it was the best we could do in time for the plan. We took two adjacent rooms with a connecting door, one for Mrs. Miller to check into with Benji, the other for us to hide in.

Four weeks after the strange odyssey had begun, the trap was finally set.

Keith, whom we had counted on for muscle, never made it. Hopping into a cab at his construction site an hour before the kidnapping was scheduled, he offered the cabbie a $10 tip and was most of the way to the hotel when the car blew a tire and skidded off the road. He ended up jogging along the highway in his construction boots and hard hat, passing stalled traffic and covering several miles, but it was too late. By the time he arrived everyone was gone except the police, who were at the hotel to investigate a kidnapping.

It was a bungled job right from the start. Fifteen minutes before the kidnapping was planned, no one had shown up except us and Dr. M., causing much consternation. At the last minute Dr. Leof wheeled in with his Mercedes, his wife and his five-year-old son in tow. He also brought Dr. G. and Dr. F., swaddled in expensive three-piece suits as though they were off to a medical convention.

We hastily outlined our plan to them, then took up our posts. We had four cars at our disposal and we used them to occupy most of the nearby hotel parking spaces, forcing Benji and whatever Moonies accompanied him to park directly in front of our room.

Dr. Leof and his family parked outside the room as well, unloading baggage like busy vacationers. Nearby, Dr. G. sat casually in another vehicle, waiting to cut the Moonies off in front, while Benji’s father manned a third car, ready to spirit away his wife and daughter.

Even Dr. Leof’s tiny son was armed with a tire valve. “Take zis, Anton,” his chic Parisienne mother had told him. “If the bad man tries to get away—phffft—you let ze air out of his tire!”

On the far side of the lot, Dr. M. was waiting nervously in the getaway car. As he sat there drumming his fingers against the dashboard, a Holiday Inn van parked directly in front of him, blocking the escape route. Dr. Leof came coolly to the rescue.

“I’m a psychiatrist here to seize a dangerous patient,” he bluffed the van’s driver, flashing a card. “The FBI is here with me—please move.”

Meanwhile Mr. Miller, Dr. F. and the four of us crouched in the darkened hotel room, peering through a crack in the curtain at some chubby women practising putts on a hotel golf green. It was 5:45 and the plane had landed fifteen minutes earlier, yet we still hadn’t heard from Mazzoni at the airport. The waiting was becoming unbearable.

The phone rang. It was Mazzoni.

“Benji’s here with another Moonie,” he said tersely. “They’ve picked up Mrs. Miller in a 1976 Mustang. Get ready!”

Several minutes later we were all nervous wrecks, when Simon broke the silence with a hoarse whisper.

“I see it…a silver Mustang. It’s coming right this way.”

A car stopped directly in front of the window.

I strained to peek through the tiny peephole without being seen, ready to give the signal to attack the instant I saw Benji. Car doors opened, obscuring my vision, legs and baggage came into view, then—swish—two pairs of legs, one female, whisked by me in a blur before I could see any higher than the waist.

The lock in the room next door clicked, but we didn’t know who it was. Was Benji in the room, or still in the car—had they switched cars on the way? Should we gamble it was him and rush in, or wait until we were sure? How big was the Moonie with him?

The silver Mustang moved slowly toward a parking spot, but I couldn’t see who the driver was. Nearby Dr. Leof and his wife appeared confused.

“What are you doing, you idiot?” I heard him yell, waving his arms at his wife, who leapt from the car and stormed off. They were trying to tell us something—but we didn’t have a clue what it was.

Lenny and Mr. Miller scrambled to the back door of our hotel room, pressing their ears against it to identify the voices in the adjacent room.

“I think I hear Benji,” mumbled Lenny, but Mr. Miller disagreed. Minutes were ticking away and Benji—if it was him—might leave any second. What the hell were we supposed to do?

Finally, in a flash of desperate bravado, Dr. Leof came to the rescue. Storming up to our room in complete frustration, he pounded on the door with all his might, and yelled so loud that half the hotel could hear:

“What the hell are you doing in there? Benji’s next door—get the hell out there and KIDNAP him!!”

As soon as Dr. Leof’s words had registered, Simon and I charged out the front door, while Lenny and Gary grappled at the one connecting the two motel rooms.

“Okay, I’ll open the door and you charge in!” shouted Gary.

“The hell,” countered Lenny. “You open the door and you charge in!”

As the door was flung open Gary burst into the room and saw Benji and his mother standing by the bathroom sink, watering a bunch of flowers. The Moonie accompanying Benji was not in the room. Gary charged, grabbing Benji in a choke hold and pulling back with all his strength—but as he did he squeezed Mrs. Miller up against the sink. She shrieked and tumbled into the bathtub, flowers covering her like a body ready for burial.

Lenny, Simon and Dr. Leof arrived and grabbed Benji from the front. His arms flailed to escape and his eyes registered what Dr. Leof later called the “most terrifying blank expression I have ever seen”. Then momentarily Benji noticed Simon, and for an eerie second he seemed to return to the Benji of old. He stopped, as in a freeze-frame of a movie, and said: “Hi Simon—what are you doing here?”

But an instant later his eyes were distant again, and he was fighting to escape as though all of us—including his parents—were total strangers. I raced outside to see what had happened to the escort Moonie.

To my horror, I saw him backing the Mustang out of its parking spot unimpeded and preparing to take off for help.

Somehow Dr. G. had dozed off and neglected to cut off the Moonie vehicle.

Racing toward the car, I pulled at the passenger door handle to no avail, then scrambled atop the hood—freezing before the windshield and staring into the Moonie’s eyes as he tried to get the car in gear.

“No-o-o!” I shouted, scrambling off the hood and diving for the door handle, praying it might be unlocked. My fingers gripped the metal, the door swung open and I flung myself into the Moonie’s lap, shouting:

“Wait! Wait! We just want to talk to Benji. Please listen! We have deportation papers taken out on Benji, but we don’t want to use them—we just want to talk…” I rambled, bluffing wildly. I was running out of steam, when Dr. G. suddenly swung into action.

Peeling his car out of its parking spot with squealing tires, he tore toward us, terrifying us and hotel guests gaping at the scene. At the last second he screeched to a stop, inches from the Moonie’s Mustang, then slammed his door and stormed toward us.

“FBI!” he snarled, shoving his open wallet briefly through the window and grabbing the Moonie by the shirt. “Out of the car, punk!” The Moonie froze, and I slapped at Dr. G’s arm and yelled in spontaneous histrionics:

“Hold it! We had a deal…you said there’d be no trouble if he let us see Benji peacefully. Don’t double-cross us!”

It was a third-rate performance, but enough to confuse the Moonie, and he jerked his eyes from one of us to the other, shouting: “What’s going on—what’s happening?” His voice was strained and his manner frantic—but as I looked into his eyes they seemed completely dead.

Back in the room, Benji was struggling to escape, though clearly shocked by the presence of his haggard father and friends in the kidnapping. Finally, Lenny rushed out to get me, hoping one more familiar face might break his resistance completely.

I abandoned my play acting with Dr. G. and ran into the room to deal with Benji. I couldn’t; as soon as I looked into his vacant, alien eyes I burst into tears.

“Damn you, Benji…” I sputtered. “We’ve spent ten thousand dollars and six weeks’ time to get out here and talk to you…just talk to you! Just…just…get out of here!”

Somehow that seemed to work. Moved by my tears and those of his parents, Benji became subdued for a moment; we took advantage of the calm to pin his arms and rush him out the door.

As we stepped out into the light, half carrying Benji, hotel guests peered down from every balcony at the spectacle—while Dr. Leof, Dr. G. and Dr. F. moved casually about reassuring them with “I’m a psychiatrist…it’s only a patient…please don’t worry”; or “FBI!…shut up and say nothing!”

In the confusion, the other Moonie raced off in the Mustang for help, but we paid no attention. Dr. M. pulled in with the getaway car; its doors opened. I fell in backward, pulling Benji by the neck, and Simon fell in on top of him, shouting: “Please Benji—please!”

Only a tangle of legs still protruded through the car door. Gary stuffed them in like so many sticks of lumber and jumped in himself; at last, the car squealed and lurched out of the parking lot and onto the nearby highway.

“Jesus…that was close!” I gasped, easing my stranglehold on Benji, only to realize that it was no longer needed. Our friend was sitting bolt upright, eyes riveted to the floor in a trance-like state he would maintain for more than 24 hours—and nothing we would say would draw him out. We tore down the highway in complete silence, wondering what we were going to do next.

Forty-five minutes later we were safely parked in the underground garage of our hotel in Berkeley, triumphant grins stretched across our sweating faces. Benji was still in a trance as we pulled him from the car.

Halfway to the stairs he kneeled to tie his shoelace, then made a break for it. We grabbed him, pinned his arms apologetically, then carried and shoved him up three flights of back stairs and down the hotel corridor. With a collective sigh, we hauled him into our own room, then piled tables and chairs against the door.

Bad news was waiting. Mr. Miller was already back at the hotel in a room down the hall, but his wife—who suffered from high blood pressure—was very faint. He was in his room waiting for a doctor, but had phoned to give us worse tidings: our own hotel room was registered in his name, and could probably be traced by anyone who called.

I rushed downstairs to the main lobby, then casually walked up to the middle-aged woman plumped at the reception counter.

She was a stern-looking Scottish matron, and she glared at me as I approached in my clearly dishevelled condition.

“Uhhh…I hate to ask you this…” I stumbled, “but could we change the registered name on our hotel room—fast!”

“And why-y-y?” she demanded, looking me dead in the eyes.

I had no choice. Swallowing, I asked her if she had ever heard of Rev. Moon.

“That bastar-r-rd!” she replied in a cold Scottish brogue. “Someone should put a bulletttt between his blades!”

“Whew,” I sighed, spilling my story quickly and begging her help. In moments, she agreed, flashing a sympathetic smile; then she raised her finger to deliver a piece of motherly advice:

“There’s just one thing I’ve been meaning to tell you ever since you checked in a few days ago…

“I’ve been in the hotel business for twenty years…but I’ve never seen guests more susss-picious than the lot of you—whispering and plotting and coming and going all night long. I had a mind to call the police myself last night—not because I suspected you of anything…you’re much too harrrmless looking for that—but because I worried you might be in some kind of trouble yourselves!”

Some time later we had settled down in the hotel room and were trying to break through Benji’s silence. His father came by to talk with him but the attempt was futile: Benji gazed by Mr. Miller as though he were a stick of furniture.

When the usually jovial father abandoned his efforts and returned to his ailing wife, there were tears streaming down his face. Benji’s sister Debbie had met a similar fate, crying “Benji—what’s wrong…BENJI!” to the brother she hadn’t seen in a year. But Benji would not so much as look up to acknowledge her.

The only momentarily brightening words had come from Mazzoni, who had phoned the room from somewhere to tell us he was “proud…you need some polish, but it was a great first kidnapping!…You guys have got a real future.”

Now I was reading Benji some material on Rev. Moon’s financial interests, in hope that some of the information might get through the screen of silence around him. We were steadying ourselves for a long night—when unexpectedly the phone rang. It was the Scottish woman at the desk.

“Come down quickly,” she growled in a low voice. “It’s very important that I see you.”

Gary hurried down to the reception desk where the woman was nervously waiting. “The police just called,” she told Gary softly. “They wanted to know if I had a Mr. Miller on my books—but I told them I didn’t give out that information over the phone. “They said they’d be coming over soon and check it themselves… ”

“Whee-eew!” Gary whistled, trying to figure out our next step. “Did they say when they’d be ov-”

He never finished the sentence: the woman had gone stiff as a board. “My God,” she whispered, the blood draining from her face.

“They’re standing right behind you now.”

Chapter 8

Our new hide-out was a small cottage with a tiny blue bedroom that served as Benji’s cell. Crowded quarters, but far more spacious than the real police cell we had all so narrowly escaped.

Only fifteen minutes earlier we’d been sitting comfortably in our Berkeley hotel room when Gary had rushed in with word that the police and Moonies were searching the building; somehow they had pinpointed our hotel. The police had been only inches from Gary, but had failed to spot him as one of the kidnappers. He had slipped between the two officers with a whispered “excuse me”, then sauntered across the lobby just as police and Moonies began flooding the hotel.

Turning down the main corridor, Gary had raced back to our room. In seconds we had grabbed Benji again and trundled him down the back stairs like a sack of potatoes. We crowded into our car and sped out of the garage; by the time we reached the street, the police were searching our room.

Luckily Dr. M. lived only a few blocks away, and we were at his house in minutes. It was cramped: the small cell-like room for Benji and a double living room for the rest of us, furnished with the sparse accoutrements of a counter-culture doctor. Some beat up furniture. An expensive stereo. A hammock. The odd stethoscope lying about. A sign on the front door read: “To be sure of hitting the target—shoot first, and whatever you hit—call the target.”

Immediately upon arriving, we began barricading the windows and stripping Benji’s room of sharp or pointed objects such as bottles and pencils. Many Moonies have been taught that it is better to die than to be deprogrammed; some have been given razor blades with instructions on how to attempt suicide, down to the precise angle at which to slash their wrists.

“Slash across for the hospital, down for death” was their chilling “razor blade rule”, and several members had used it in the past. We didn’t know if Benji had learned the “technique”—but looking at him, we weren’t going to take the chance.

Our friend’s appearance was appalling. Emaciated and pale, the once gregarious Benji sat with his eyes bolted to the floor, their black pupils twice normal size. He had gone into some kind of trance to avoid speaking to us, mutely chanting what we later discovered was: “Glory to Heaven. Peace on Earth. Get me out to serve whole purpose.”

“Benji!” we shouted again and again in complete frustration, as though shouting at someone who was out of earshot. “What are you doing—why don’t you talk to us? All we want to do is discuss this thing with you—make sure you know what you’re doing…Benji—this is crazy…why won’t you just talk about it?”

It was like speaking to a corpse. Hour after hour he sat as rigid as a block of stone, back erect, gazing into space as though we were not even present. His transmogrification was shocking and utterly incomprehensible; for the first time since the strange odyssey had begun, all of us knew we had done the right thing in grabbing our friend. And we also knew that we needed a “deprogrammer”, if we were ever going to reach him again.

For the rest of the evening, we kept at least one person talking with him at all times, to no avail. At eleven p.m. Benji silently turned over and dropped off to sleep. We laid a blanket over him, turned off his light and called Montreal to bring our anxious friends up to date. Following some discussion, we called Neil Maxwell and several other San Francisco contacts; after weeks of delaying the decision, we asked them to help us find a deprogrammer.

Soon afterwards, we settled down to guard duty and flicked on the television for diversion. By a startling coincidence the screen was filled with the face of Sun Myung Moon, who had rented a half hour of TV time to “talk to America”. For the next thirty minutes, Moon’s shrill voice and karate-chop gesticulations filled our little outpost in a frightening display. It included a tape of a $1 million firework show the Moonies had sponsored in Washington, and a passionate appeal by Moon himself for God to “Bless America” in the holy war against the communist devil.

“MAN-SEI!!” shrieked 1500 Moonies, dropping to their knees before Moon and saluting skyward with clenched fists that seemed to come from a single body. “VICTORY FOR FATHER!”

We spent the night in a watchful vigil, alternating sentry posts from Benji’s room to the front and back windows of the house—though there was little we could have done had the police or Moonies arrived. As darkness blanketed the city, the ordinary noises of night began to seem like enemy activity: the rustle of trees and windows sounded like prowling strangers, the barking of neighbourhood dogs was mistaken for approaching bloodhounds. Even the wail of the occasional ambulance convinced us that a full-scale police dragnet was hunting us in the streets.

Despite our paranoia, one sound still amused us: Benji’s buzz-saw snoring—the only thing about him that hadn’t changed. It reverberated through the tiny house all night long, like an eerie musical score.

The still night was fertile ground for moral unrest too, providing the chance to ponder and discuss our strange venture. We had run on instinct all the way through the kidnapping, and now that it was over, many thoughts raced through our minds. Had it made any sense to kidnap Benji? It was obvious he did not want anything to do with us. But was the person in the next room really Benji—and what would the old Benji have to say? Would we ever see him again to find out?

What of the deprogrammer? Were we right to call one in, and what would he be like, if he ever showed up? One thing we were all agreed upon: regardless of what the deprogrammer had to say, we would not keep Benji captive indefinitely. If he didn’t start talking in the next couple of days, we would have to let him go—whatever the consequences.

And what would happen if we were caught? There were more than 40 people involved in planning the kidnapping—how would they ever bring us all to trial? “Hell of a good story!” I scribbled into my notebook, alongside the tangled thoughts of the night’s writing; it was the newsman in me, returning for the first time in a long while…

Several hours and cups of coffee later, morning peeked through our tightly shuttered windows. All of us were haggard and disconsolate, and I decided to chance calling the Berkeley hotel to speak with Benji’s father for advice; we had had no word from him since our flight from the hotel. The phone rang several times. When Mr. Miller finally answered, he was nervous and brief:

“Josh…I can’t talk…the police are outside our door,” he whispered. “We seem to be under arrest.”

For Charlie Miller and his family, events had moved quickly from the harrowing to the horrid. The kidnapping had been the most distressing moment of Charlie’s life: his son Benji, virtually unrecognizable behind the strangely flat gaze that failed to respond to his own family; his wife Libby crying as the “boys” had grabbed Benji; himself so nervous he could not even bear to look, let alone help subdue his son. When the “boys” had finally stuffed his son’s flailing body into the getaway car, Charlie had held his wife in his arms as she cried for them to let Benji go; then he had hustled her and his daughter Debbie into another vehicle and careened away from the hotel.

The drive had been a nightmare; watching for police, worrying about Benji, listening dumbstruck to his wife’s description of her airport encounter with her son. “It wasn’t Benji, Charlie, it wasn’t him at all. He’s so pale and skinny you could die…and his eyes!…What have they done to him?!”

Then the news that the Moonie accompanying Benji was his nephew; Charlie hadn’t seen the boy since he’d left home three years earlier. A police car passed and Charlie winced at the sight for the first time in his life. Beside him, he could see that Libby was pale, her blood pressure acting up despite her stoic efforts.

At the Berkeley hotel, matters were even worse. The brief encounter with his son seemed to Charlie to be the nadir of his existence. He had fled back to look after his wife, more convinced than ever that Benji was lost.

Soon after, he had heard a commotion in the hotel corridor—as we rushed by with Benji—but he had hesitated to look out for fear it was the authorities; then, even as he could hear our receding footsteps, the police had come lumbering up the front stairs to pound on his door.

“Mr. Miller…Sergeant Sullivan, San Francisco Police.”

The officer was a stocky, florid man, with a puffed face and a large pot belly: he wanted to know where Benji was.

“I haven’t got the faintest idea,” said Mr. Miller to the skeptical officer, as the two paunchy middle-aged men squared off against each other. The policeman was demanding, obviously uncomfortable with his task. He shrugged nervously and told Charlie:

“I hate doing this, Mr. Miller…I have a wife and children at home too, you know.”

Eventually, Sergeant Sullivan had confined them to their room, indicating that formal kidnapping charges would soon be brought. He told the Millers to “get smart” and tell him what had happened by morning. Before leaving, Sullivan had pointed suspiciously at Mr. Miller’s file, crammed with information on the Moonies; it was labelled “BBB”—an acronym for “Bring Back Benji”.

“What do the letters stand for, Mr. Miller?” asked the sergeant.

“Nothing…” replied Charlie. “J…just scribbling.”

“Hmmm…” said Sullivan, with a whimsical smile. Then he stuffed the file into his own dossier; it was labelled “MM”—short for “Missing Moonie”.

When Sullivan left, no one in the family could sleep, despite their complete exhaustion. Mother and daughter lay awake on the bed the entire night, convinced they would soon be arrested; nearby, Charlie sprawled flat on his belly by the window. All night long he peered out the curtains at three police cars parked outside, pondering the unimaginable circumstances that had so changed his life. His only hope was the “boys”, and the chance that they would somehow find a way to reach his son.

At nine a.m.—shortly after our call—there was a sharp knock at the hotel room door. Charlie opened it cautiously, expecting to see the police with a warrant for his arrest. It was a thin young man in a suit, a lawyer named Larry Shapiro sent by Dr. Leof to look after the Millers. He had bad news: the Moonies were assembling in the hotel lobby to hold a press conference about the kidnapping; a lawyer for the Unification Church had declared that if Benji were not back within 24 hours he would go to the FBI.

Within minutes, the Millers were following the young lawyer out of the hotel. As they moved through the main lobby, the Moonie lawyer was already giving a statement to the assembled news media; flashbulbs clicked and reporters clustered around the Millers as they moved briskly through the throng, refusing to make any comment. Outside, they scrambled into the back of the lawyer’s car and drove quickly away; but several Moonies rushed to three waiting vans and trailed them down the street like a strange parade.

A hectic fifteen minute car ride later, the Millers arrived at the lawyer’s office, with no sign of the Moonie vehicles behind them. Shortly afterwards, as they were sipping coffee, another young law partner stepped into the office, bewildered. “There are some pretty strange-looking people outside the office,” he said innocently, still unaware of his partner’s peculiar new case. “They look like Moonies…what the heck do you think they want?”

There was a rap at the window. A group of short-haired young men were standing outside, holding trays of coffee and cake and signalling for the lawyer to open the window. Behind them, several other youngsters dressed in white were busy sweeping the law firm’s patio, in a scene reminiscent of a Fellini film.

“Jesus Christ!” exclaimed the lawyer, and seconds later he and his partner were assisting the distraught Millers downstairs to the garage. They split up into two cars. One of the lawyers drove out of the garage as a decoy, the other followed with the Millers several minutes later. The ploy was partly successful. When Charlie looked out the back window minutes afterward, only one van was still in pursuit.

The next ten minutes was a high speed chase, the Millers’ car swerving around corners and down back streets in an attempt to shake the remaining van. It was no use. As they sped out onto the entranceway of the busy Golden Gate Bridge, the Moonies were still close behind. Then, as they approached the bridge’s toll booth, the Moonies committed a blunder, pulling into one of the pay tolls ahead of the car they were tailing. The lawyer in the Miller’s car acted quickly.

“Excuse me…This is an emergency!” he told the elderly guard at the toll booth window, as the Moonie van was forced ahead onto the bridge by heavy traffic. Pulling out every identification card he could muster, the lawyer convinced the guard to stop the traffic and let him turn around. The old man emerged reluctantly from his booth and began to bring four lanes of traffic to a halt.

Once traffic had been stopped, the young lawyer drove his car over the frozen car-jam to the other side of the highway—only to see the Moonies’ van heading back their way. The Moonies had seen their mistake, and somehow managed to wheel their vehicle around on the bridge. The lawyer thought quickly. He peeled his car back across the four lanes of stalled vehicles, then charged by the startled guard and through the toll booth—right by the Moonie vehicle, which was mired in frozen traffic going the other way.

“Whew…that was pretty good if I say so myself,” said the slightly smug voice of the attorney, as he pressed the gas pedal to the floor. In the back seat, Mrs. Miller’s face was pale, her eyes closed, still tensed for the sound of crunching metal. Up in the passenger seat, Charlie Miller let out a long whistling breath and smiled broadly. He never saw the Moonies again.