▲ The Moon family gathers for a typical birthday celebration for one of Sun Myung Moon’s children. The fruit is piled high on the offering table in front of us. I am in the back row, second from the right. Hyo Jin is in the same row at the very end.

In The Shadow Of The Moons: My Life In The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Family

by Nansook Hong 1998

Chapter 6

page 112

I was pregnant with Sun Myung Moon’s grandchild at the same time that he and Hak Ja Han Moon were expecting their thirteenth baby.

Mrs. Moon’s obstetrician had warned her after the birth of their tenth child that another pregnancy could endanger her health, if not her life. The Reverend Moon simply had her change doctors. He was determined to bring as many sinless True Children of the Messiah into the world as possible.

However, the Moons were less committed to rearing those children. No sooner was a baby born to True Mother and True Father than it was assigned a church sister who acted as nanny and nursemaid. During my fourteen years in East Garden, I never saw the Reverend or Mrs. Moon wipe a nose or play a game with any of their children.

The Reverend Moon had a theological explanation for the kind of parental neglect he and Mrs. Moon exercised and that I had endured in my own childhood as the daughter of two of his original disciples: the Messiah came first. He expected believers to dedicate themselves to public proselytizing on his behalf; the pursuit of personal family happiness was a self-indulgence.

The Reverend Moon even designated particular couples among his original disciples to assume responsibility for the moral and spiritual development of each one of the Moon children. Assuming those parental duties himself, the Reverend Moon argued, would distract him from his larger mission: the conversion of the world to Unificationism.

Sun Myung Moon was not unaware of the bitterness this attitude engendered in his children. “My sons and daughters say that their parents think only of the Unification Church members, especially the 36 Couples,” the Reverend Moon said in a speech in Seoul just months before my wedding. “I eat breakfast with the 36 Couples, even chasing my own sons and daughters away. The children naturally wonder, ‘Why do our parents do this? Even when our parents meet us someplace, they don’t really seem to care for us.’

“It is undeniable that I have loved our church members more than anybody else, neglecting even my wife and children. This is something Heaven knows. If we live this way, following this course in spite of our children’s opposition and neglecting our family, eventually the nation and the world will come to understand. Our wives and children will understand, as well. This is the kind of path you have to follow.”

Apparently the Reverend and Mrs. Moon had little idea of the real trouble that was brewing along that path. Soon after I enrolled at Irvington High School, In Jin and Heung Jin transferred there from Hackley. Father claimed he had abandoned the private school because his children were being tormented by teachers who mocked them as Moonies, but the truth was that some of the Moon children were terrible students. Once in public school, they adopted the dress and slang and behavior of their most wayward classmates. They even assumed Western names to use among their new friends. In Jin, for instance, called herself Christina for a while, and then Tatiana. When Hyo Jin joined them for parties, he called himself Steve Han.

It wasn’t only through their assumed names that the older Moon children sought to distance themselves from the True Family. Most took a perverse pleasure in ignoring every tenet of their religion. The Moons paid scant attention. They had more public problems to contend with that spring: Father was about to stand trial for being a tax cheat.

The previous fall, only weeks before Hyo Jin and I were matched, an indictment had been handed up against Sun Myung Moon in federal court in New York. He was charged with filing false personal tax returns for three years, failing to report about $112,000 in interest earned on $1.6 million in bank deposits, and failing to disclose the acquisition of $70,000 worth of stock. An aide was charged with perjury, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice for lying and fabricating documents to cover up the Reverend Moon’s crime.

The Reverend Moon returned to the United States from a trip to Korea to plead not guilty to those charges. Father told twenty-five hundred cheering supporters on the steps of the federal courthouse in New York that he was a victim of religious persecution and racial bigotry: “I would not be standing here today if my skin were white and my religion were Presbyterian. I am here today only because my skin is yellow and my religion is the Unification Church.”

Father had made similar pronouncements earlier that year when a jury in Great Britain concluded at the end of a six-month libel trial that a national newspaper, the Daily Mail, had been truthful in describing the Unification Church as a cult that brainwashed young people and broke up families.

The High Court jury described the church as a “political organization” and urged the government to consider rescinding its tax-exempt status as a charity. The jury also ordered the Unification Church to pay $1.6 million in court costs at the end of the trial, the longest and costliest in British history.

In the New York tax case, Father had been released on a personal recognizance bond of $250,000, cosigned by the Unification Church and one of its umbrella corporations, One Up Enterprises. The trial began April 1. Despite the advanced stage of her pregnancy, Mrs. Moon accompanied Father to federal court every day. Un Jin and I went only once. I did not understand a single word of the proceedings because the language barrier, but I did not need to understand what was being said to know what was happening in that courthouse. Sun Myung Moon was being persecuted, not prosecuted.

Father had explained to us that what was happening to him was part of a long history of religious bigotry in the United States. Even though early settlers came to North America seeking religious freedom, they had found intolerance instead. In his Sunday-morning sermons at Belvedere, he told us of innocent women who had been tried and hanged as witches in Massachusetts, of Quakers who were stoned in the South, of Mormons who were murdered in the West. The Internal Revenue Service investigation that resulted in Father’s trial was part of that shameful tradition.

Every morning there would be a pilgrimage of family and staff to Holy Rock, a clearing in the woods on the eighteen-acre East Garden estate. Father had blessed as sacred ground this spot high on a hill above the Hudson River. It was a beautiful, unspoiled place. Praying there I felt closer to God and further from the twentieth century than in any other place I had ever seen. It was a place for quiet contemplation, looking little different in 1982 than it did when Henry Hudson first explored this area of the continent in 1609.

Father prayed at Holy Rock alone before dawn every day. The prayer ladies, older women including my mother, held vigils there every day of the six-week trial. Sometimes the True Children and Blessed Children from the surrounding area would meet there to pray for Father’s exoneration. I remember how cold it was on that hill. I was pregnant and my joints would ache from the chill, but my discomfort was small next to the suffering Father was enduring.

There were tears when Father was convicted in May, but I’m not sure that anyone, outside the inner circle of the Reverend Moon and his advisers, understood the gravity of his situation. None of us really believed that U.S. District Court judge Gerard Goettel would do what was in his power and sentence Father to fourteen years in prison. The gloom in East Garden about Father’s conviction for tax fraud had been offset by the ruling of a separate court in New York that the Unification Church was a genuine religious organization and entitled to tax-exempt status.

Two months later, Judge Goettel sentenced the Reverend Moon to serve eighteen months in prison and pay a twenty-five-thousand-dollar fine. Father accepted the sentence stoically. In the Reverend Moon’s scheme of things, his imprisonment — his martyrdom — was providential. Mose Durst, president of the Unification Church of America, even compared Father’s conviction to that of Jesus Christ “for treason against the state.” The Reverend Moon’s lawyers filed an immediate appeal. “We have the utmost faith that through the court system in America, justice will be done and our spiritual leader fully vindicated,” Mose Durst told the press. “As with all of the world’s great religious leaders, he has been met with hatred, bigotry and misunderstanding.”

In response to threats by prosecutors to have the Reverend Moon deported, the church hired Harvard Law School professor Laurence Tribe, an expert on constitutional law, to handle his appeal. Professor Tribe argued successfully that deporting Father would deprive him of contact with his six American-born children, who then ranged in age from two months to ten years. Judge Goettel agreed that deportation would be “an excessive penalty,” though he acknowledged that the public animosity toward the Reverend Moon made this “a difficult decision, one that is bound to be unpopular with a lot of people.” Father was allowed to remain at home, pending the outcome of his appeal.

Father seemed unfazed by his conviction. That summer, when Hyo Jin was in Korea again, I accompanied the Reverend and Mrs. Moon to Gloucester, Massachusetts, where the church owned fleets of fishing boats and a processing plant. The Reverend Moon has said he founded the so-called Ocean Church to feed the world’s hungry. We all suspected he bought the fleets because he likes to go fishing. In Gloucester, Father owns Morning Garden, a mansion he purchased from the Catholic Church. (All of the Moons’ residences had names designed to evoke the Garden of Eden: there was East Garden; Morning Garden; North Garden, in Alaska, where Father also owned a fishing fleet and two giant fish processing plants in Kodiak and a third in Bristol Bay; West Garden in Los Angeles; South Garden in South America; and yet another enormous estate in Hawaii.)

That summer, Father also rented a house in Provincetown on the tip of Cape Cod so he could fish even more. It was my responsibility to wait on Mother and the children on the beach while the kitchen sisters who accompanied us prepared meals. I would serve the family lunch on the beach, dry off the children after swimming, and generally act as Mrs. Moon’s lady-in-waiting. It was a frustrating and thankless job. I could not swim unless she swam. I could not take a walk unless she did. I could not even visit the bathroom unless I was accompanying her. I was there to wait on her, no more, no less. At night I slept in a sleeping bag surrounded by her children, her cooks, and her maids. She boasted that she was providing us all with a relaxing vacation, but she and the children were the only ones who looked relaxed to me.

Despite my own pregnancy, I felt like a servant child in the Moon household. In East Garden, when the Moons were in residence, I was required to rise before they did and wait outside their bedroom for them to awaken. It was my duty as their daughter-in-law to serve the Moons their meals and to attend to Mrs. Moon’s needs throughout the day. When I was not at school and on the weekends, I was at Mrs. Moon’s side from morning until night. I spent most of this time waiting to be called upon to fetch her something, to serve her something, or to accompany her somewhere. I spent hours watching videotapes with her of the mindless Korean soap operas she enjoyed and I abhorred. I had to pay attention, though, in case she commented on the plot.

I ate my meals in the kitchen with the other children, while True Parents dined with church leaders and visiting dignitaries. We learned of developments in the tax case through whispers; Father never spoke with us directly about his situation. We were only children in his eyes.

I can’t say that I disagreed. The kitchen was the one place in the compound that felt like a real home, with the little ones spilling their milk and the older ones chatting about school. I often fed Yeon Jin in her high chair. Hyung Jin was just a toddler. I would take him from the big round table in the kitchen out onto the hills of East Garden, where we would pick wildflowers. I grew up with the Moon children, more a sibling than a sister-in-law.118

I would go with Un Jin sometimes to New Hope Farm, the horse farm that the Reverend Moon had purchased in Port Jervis, New York. An accomplished equestrian, Un Jin loved horses. The South Korean Olympic equestrian team trained there. Thanks in large measure to Sun Myung Moon’s money, Un Jin would become a member of that Olympic team in 1988.

Heung Jin was the only other older Moon child who showed me much kindness my first year in East Garden. He was just a few months younger than I. He was a sweet boy. He kept a cat in his room. When she had kittens he could not bear to part with any of them, so they took over his room. Sometimes we would find Heung Jin sleeping in the small telephone alcove next to his bedroom because the cats had made it impossible for him to slip into his own bed. My first winter at East Garden, he had given me roses on my birthday, a gesture especially memorable because Hyo Jin did not even buy me a card.

I went to language school that summer and fall, trying to master English and disguise my advancing pregnancy from my older, mostly Spanish-speaking, classmates. Mrs. Moon had sent my mother back to Korea that summer to look after my younger siblings, so I found myself lonelier than ever in East Garden. My pregnancy was a more frightening than joyous adventure. I was plagued with debilitating morning sickness that I was too young to know would pass. I worried there was something terribly wrong with me or with my baby.

Hyo Jin was rarely at home. Whenever he got bored, which was frequently, he would announce that he was going to Korea for a “seven-day course” or a “twenty-one-day course,” church training programs designed to bring one closer to God. Despite his announced intentions, word usually filtered back from Seoul that Hyo Jin was spending his time with bar girls or his old girlfriends. When he was at East Garden, he demanded sex every night, despite my protests that it was terribly painful. More upsetting than the pain was the disgust he expressed as my waist and hips expanded with our growing child. For me, it was a miracle. For him, it was an affront. He called me fat and ugly. He made me cover my tummy when we had sex so that he did not have to see.

The Reverend Moon would say that I needed to pray harder for Hyo Jin to come back to God, that soon fatherhood would change him. Not incidentally, he said we must all pray for the health of the baby I was carrying. No one spoke of it above a whisper, but I knew that everyone in East Garden feared the baby might suffer the consequences of Hyo Jin’s insatiable appetite for drugs and booze and unprotected sex.

I went to Lamaze childbirth classes alone. A driver would drop me off with my two pillows at Phelps Hospital. Every other pregnant woman was there with an attentive partner. The teacher paired me with a nurse who was studying the Lamaze breathing and exercise techniques. I felt that God had sent her to help me. Grateful as I was, my heart ached looking at all the loving couples, preparing for the birth of their babies. The women chatted about crib styles and car seats. They debated the merits of cloth versus disposable diapers. The men looked awkward but proud, placing their palms gently on their wives’ bellies to feel the babies move inside. Hyo Jin had just scoffed when I asked if he would like to try. I spoke to no one for six weeks of classes. I wondered what they thought of me. I was alone and so much younger than all of them. I must have looked pitiable. I had to accept during those classes the truth that I pushed from my thoughts each night: Hyo Jin did not care about me or our baby.

My mother returned to East Garden in January in anticipation of the birth, which we expected in early February. She slept downstairs in Cottage House. It was good she was there because on February 27, when I began to have contractions, my husband wasn’t. I was three weeks overdue. Hyo Jin had returned from Korea, but despite the impending birth, he went to New York every night to the bars. That’s where he was when I went into labor. My mom walked me around the house to ease my discomfort, but at 10:00 p.m. we finally called the doctor, who told us it was time. Hyo Jin had not bothered to leave a telephone number where we might reach him, so an East Garden security guard drove me and my mother to the hospital.

I was terrified. Even on the fifteen-minute drive from East Garden to Phelps Hospital, the pain intensified. I could not believe what was happening to my body. I had not missed one childbirth class; I had read up on labor and delivery; but nothing prepared me for the searing pain that ripped across my belly with each contraction. I could not sit comfortably in the car. I felt every pothole or turn in the road like a knife in my womb.

My mother stayed with me during that long, sleepless night. She held my hand and dried my tears when the pain came. Every hour I would beg the nurses to check to see if I had dilated enough to deliver this baby. One centimeter. Two centimeters. My cervix opened as slowly as the hands of the clock turned. I thought the night would never end. I thought my skin would split open. I thought I would die.

Hyo Jin did not come to the hospital all night. When he did come in the morning, he looked hungover and did not stay long. He watched the waves of pain pass over me as each contraction crested. He saw me cry. He heard me moan. Then he fainted. It was quite a sight, this man who thought he was so tough splayed out on the labor room floor. The nurses laughed as they helped Hyo Jin to his feet. If I had been in less agony, I might have seen the humor. Instead I saw only that once again he would leave me alone when I needed him.121

In the waiting room, Mrs. Moon huddled with the prayer ladies and fortune-tellers. They sent word to the labor room that the baby must be born before noon in order to achieve the best future. The doctor was willing to help. “If that’s your culture, I’ll do what I can,” she said. My mom had to wait outside the delivery room, so I depended on the compassion of the nurses to pull me through. They were wonderful, although I confess wanting to strangle them when they laughed at my impotent pushes. The baby’s head would emerge and then retreat. I just didn’t have the strength. The doctor performed an episiotomy and used forceps to ease the baby out of the birth canal.

It was a girl. She had a mass of black hair. She had red marks on her face from the pressure of the forceps. Her eyes were closed. I felt sorry for her. She was so small and fragile looking —just under seven pounds — that I was afraid to hold her. I could feel the nurses’ disapproval. They exchanged glances when I did not take the baby right away. I worried that they thought I didn’t love my daughter. Nothing could have been further from the truth. I was just so young and so scared.

In the waiting room, news that the baby was a girl was greeted with the disappointment I had expected. It was my duty to produce a grandson and again I had failed the Moons. The reaction would have been the same in Korea, even had I not been a member of the Unification Church. Boys are still valued more highly than girls in my culture. But my responsibility to produce a son was tied to the future of the Unification Church. As the eldest son of True Father and True Mother, Hyo Jin Moon would inherit the mission of the church. It was my duty to deliver the son who would follow Hyo Jin as the head of the church.

I was overwhelmed by feelings of incompetence after the birth of Shin June. She could not latch on to my nipple and the nurse and I could not figure out how to help her. The nurses on the maternity ward were impatient with my youth and my difficulties with English. But I knew then what women mean by maternal instinct. I had never seen anything as miraculous as my baby’s tiny fingers. I had never felt anything as soft as her translucent skin. I had never heard a more reassuring sound than her gentle breathing. Even though I did not know what to do, I looked at my baby and felt a love I had never known before. We would figure it all out together, God, my baby, and I.

The baby and I were discharged from the hospital at 1:30 p.m. on March 3. Hyo Jin drove us home to East Garden in Father’s car. The Reverend Moon was waiting at home to bless the new baby. He prayed, pointedly I thought, that God would work to restore Hyo Jin through the baby’s birth. But there was to be no miraculous change in Hyo Jin’s behavior. He stayed with us on our first night home from the hospital. After that, though, it was back to the bar scene.

My mom remained at East Garden for several months to help with the baby. I felt guilty for needing her as much as I did. The ease with which she cared for Shin June only underscored my own fumbling manner. I would have been lost without my mother, but it pained me to leave her awake all night with the baby while I slept. As much as I loved my baby, maybe because I loved her so much, this was one of the loneliest periods of my life.

I began to keep a diary after my daughter was born. To read it now is to weep for the girl I once was. The diary itself is testament to my youth — the cover is a portrait of Snoopy, the canine cartoon character.

March 6, 1983: “Hyo Jin came home at 2:00 a.m. last night and slept through until two o’clock in the afternoon. Then he went out with Jin-Kun Kim.”123

Eight days after a baby’s birth in the Unification Church, a ceremony of dedication is performed. The number eight signifies a new beginning in Unificationist numerology. The ceremony is not a baptism, since we believe that Blessed Children are born without original sin on their souls. The dedication is more of a prayer service to thank God for the birth of the new child.

On March 7 we held such a ceremony for Shin June. My diary records the event: “Hyo Jin was holding the baby. Father prayed. We passed the baby among us. Everyone kissed her cheeks. During breakfast. Mother was holding her the whole time. She was in a good mood. She said the baby looked just as Hyo Jin did when he was born. Father said her eyes were like those of a mystical bird and that this meant she would be witty. Westerners have round eyes that show what they are thinking. Easterners’ eyes are dark pools that can’t be penetrated. Father said this means we have a bigger, deeper heart.”

The next evening, only five days after Shin June and I came home from the hospital, Hyo Jin left for Korea. He did not have to go; I think he wanted to get away from us, from the responsibility that the baby and I represented. “I try to think that I am less sad than other times, since the baby is with me. But after I put her to sleep and came to my room, I was overcome with loneliness. It seems like there is a big hole in my heart and I am very sad and empty,” I wrote in my diary. “I pray to God for Hyo Jin’s safe arrival in Korea. I thank God for giving me my baby so I can fill this lonely, empty, and sad heart. Tears keep pouring down.”

I wanted so much for Hyo Jin to share my joy at the birth of our precious daughter, but I knew we were not in his thoughts once he arrived in Korea. “I wonder if Hyo Jin arrived safely in Korea. Even though I asked him to give me a call when he arrives, I don’t expect it,” I wrote in my diary. “I am going to wait several days and then I am going to call him. I decided I am going to capture many beautiful pictures of the baby and send some to Hyo Jin.”

It was not easy to capture those photographs in the early weeks. Like most babies, Shin June had trouble establishing a regular sleep schedule. She would cry all night and sleep all day. My mom was exhausted and I was wracked with guilt. “My mom raised her children and now she is raising her grandchild. I feel guilty to make her suffer like this. I really don’t know much. I feel guilty toward my baby and I thank my mom,” I wrote. “I gave her a bath. I washed her hair and put her in the bathtub. I couldn’t even wash her with soap and my mom finished her bath. I thanked my mom and I felt ashamed. I feel bad and guilty toward my little girl. I feel very inadequate as a mother. I want to be a good mother but there are so many things that I don’t know. I cannot stop feeling guilty toward her.”

Days went by and still Hyo Jin did not call and still I waited. “I wonder what Hyo Jin is doing now. I wonder if he is thinking about his daughter even a little bit,” I wrote. “Father asked, ‘Did Hyo Jin call?’ I felt bad since I had to answer no. I heard that Hyo Jin gave a talk to leaders about the wife’s role. I wonder what he’s doing right now.”

I was not feeling well physically after the birth. Korean women take extra care to protect themselves after a baby’s birth. We wrap ourselves in several layers of clothes to ward off the cold. No number of layers could keep away the chill I felt. I had never been sickly, but I was small. My body was not ready to give birth. I had pains in my joints that would worsen with each pregnancy. That March my emotional, physical, and spiritual miseries were in competition with one another. “My eyes are hurting all day long. My teeth are sensitive, so that I can’t eat anything. I don’t know why I don’t feel well. I have a headache and my heart is heavy. I have to breast-feed the baby a little later. I feel bad toward her,” I wrote. “I wonder what Hyo Jin is doing. He doesn’t call. I don’t even think about it, but I am still waiting for his call.

“It has been a long time since I prayed with all my heart. I became lazy after the baby was born. When I was pregnant, I was more conscientious and diligent in praying for the sake of the baby. But after the birth, I think I became inattentive. When I am down and disheartened, when I think of Hyo Jin, I look at the baby. Then my heart is filled with hope. She is all my hope. My only hope lies in her and I pray that Hyo Jin will come back. Once again, I thank God with all my heart for giving me my daughter. Amen.”

March 18, 1983: “It’s been raining hard since morning. The wind is also very strong. I’ve been sitting in front of my desk and loneliness fills my heart. I feel that I am all alone in this world. I often feel that there is nobody with me and I am removed from everybody. Even though my baby is in the next room, I feel like I am all alone… .”

March 19, 1983: “I had bad dreams yesterday and the day before yesterday. In the dream, Hyo Jin was with two other women even though he was married to me. I don’t even want to think about it, but the dreams were very real. They are so vivid that it seems as if they are not dreams, but real. I can remember the women’s faces so clearly. I have never seen them before. Last year when Hyo Jin brought his girlfriend to New York City and didn’t come home for a week, I dreamed twice that he was with her. I knew her, but I don’t know the women that I dreamed about this time. There were two different women on both days. Anyway, it is not a good dream. I don’t know why I am dreaming this kind of dream. Maybe I am thinking about him too much! Or maybe this is Satan’s test! I have no appetite and I think I am getting weak spiritually. Before I gave the baby a bath, I called Hyo Jin. I don’t understand why it is so difficult for him to call me. When I am alone or try to sleep, I can’t stop thinking things about him. I try not to think but the thread of thought continues. I don’t know why I am like this. I am afraid to be alone.”

March 22, 1983: “Mom scolded me because I didn’t eat breakfast because I have no appetite. I lost my appetite since having those bad dreams. Mom told me that if I become physically weak Satan will invade, so I should eat, thinking I am biting Satan! I heard Hyo Jin is doing well at the workshop but I still have bad dreams. Maybe Satan is testing me. I think I have become mentally and physically weak. I shouldn’t lose to Satan. I should quickly get stronger physically and fulfill my responsibility to God, Hyo Jin, and our daughter.”

March 27, 1983: “The rain and wind are very powerful. In spite of the bad weather and her tiredness, my mom went to Holy Rock for an hour at three o’clock. My poor mom and dad. I feel that they are not well and always suffering because of their daughter, because of me. I wonder whether Hyo Jin is doing well in the workshop, and what he is doing. I heard from my mom that on the sixth day he called his two girlfriends for an hour each! Satan invaded on the sixth day. Our Heavenly Father, how he is watching Hyo Jin and is worried. Our poor God.”

March 31, 1983: “I was angry for no reason yesterday. Maybe it is Satan’s test. I couldn’t control myself. Since the birth of the baby, I cannot fit into my old clothes. I have been somewhat worried about that these days. I told myself, I shouldn’t be doing this. I am seventeen years old now. I should be doing things and going places, but I have a baby and I have become a middle-aged lady. What a pathetic girl I am! I even regret being here. Why am I like this? Heavenly Father does not feel happy and I feel repentant. Yet I still feel that it is better to meet an ordinary man and receive his entire love. I know I shouldn’t think like this. I repent, Heavenly Father!!”

April 4, 1983: “Monday, 2:00 a.m. When I write in the diary, I think about what I did today. Well, how did I spend the day? During the day, I try to forget about my situation, but while I write in the diary I organize my thoughts. I always feel empty inside. Is it because of him? While waiting to feed the baby when she wakes up, I read the letter that I found. It’s a letter from the woman in L.A. Previously, I ripped up old letters that I have found from his other girlfriends. I don’t know why I didn’t tear up the new letter. I don’t have any feelings about the letters. I am not even angry. I think about this as a pathetic situation. I wonder how I became like this. I am not upset at the women he is dating. I feel pity for them. The person I am upset with is Hyo Jin.”

Hyo Jin did not return to East Garden until summer. Our daughter, a tiny newborn when he left, was by then a bright-eyed babbling baby. He seemed just as indifferent to her as he was when he went to Korea. I was at a loss, fearful for our future. That summer the Moons decided I could not return to Irvington High School. They worried that public school officials could get too curious about the cause of my extended leave of absence, that there would be rumors about the baby. I was still below the age of consent in New York when she was conceived. They did not need their son accused of child abuse or even rape.

I was admitted to the Masters School, a private school for girls in Dobbs Ferry, New York. I was very excited. I had been yearning to go back to school since spring. In my diary in April, I had written: “I should study very soon. I also have to practice piano. I am just wasting my time, not doing anything. I have to make plans to study.” School would be a distraction from my loveless marriage and my depression. It would make me a better mother. I was full of hope for the first time since coming to East Garden.

One morning the Moons called me to their room. I was alarmed. When they sent for me, it usually meant I had done something wrong in their eyes. I never knew which one of them would be angry at me. Both of them had horrible, raging tempers, but they rarely were angry at the same time. This time it was Mrs. Moon who began shouting as soon as I fell to my knees to bow to them.

Did I know how much the tuition was at the Masters School? Did I have any idea how much money it would take to educate me? Why should they be burdened with this expense? I was not their daughter. They already had to pay to feed and clothe and house me. How much more did I want? She could barely speak, she was so furious. The Reverend Moon said nothing while she ranted. I kept my head bowed, bit my lip, and began to cry. I thought I had done everything the Moons wanted. I married their wayward son. I stood by him even when he left me, pregnant, for his girlfriend. I had given them a beautiful granddaughter. Why was Mother screaming at me?

Mrs. Moon said that Bo Hi Pak’s daughter had received her high school diploma through a correspondence course. I could do the same. What did I need with a fancy education? I could do what Hoon Sook Pak had done. She was a ballerina now. It had all worked out. I could study at home and care for the baby at the same time.

I was stunned. My parents had always valued education. They sacrificed their own comfort to ensure that their seven children had the best schooling available. The Moons were going to let me get a diploma through the mail? I knew that I needed to go back to school, to see people my own age, to get out of the Moon compound for part of my day. I was so grateful when the Reverend Moon finally spoke up. Those correspondence courses are no good, he told Mother quietly; we have to send Nansook to school.

The two of them discussed the options as if I were not there, on my knees sobbing before them. They made every important decision about my life and then blamed me for the repercussions. I tried to will my tears to stop. I had done nothing wrong. I should not be crying. I could not help myself, though. When she had fully vented her rage, Mrs. Moon suddenly remembered I was still there. “Get out!” she shouted. I scrambled to my feet and tried to avert my eyes from the staff as I rushed down the stairs and back to Cottage House.

The entire summer went by with no mention of my education. One day in September, I was simply told that I would begin the eleventh grade the next day at Masters School. I was driven to and from school that year. In my senior year, I learned to drive. Hyo Jin had offered to teach me, but after one session of his screaming abuse, I told him I preferred to learn from one of the security guards at East Garden. It was the first time I had stood up to Hyo Jin. I knew I was not going to learn if he shouted, and he would not stop shouting. I even learned to parallel park, without ever leaving the Moon property.

I loved the Masters School. The academics were challenging and the student body included several Korean girls. Most of them were musicians, studying at Juilliard at Lincoln Center in New York City on the weekends. To them I was just another teenage Korean expatriate being educated in the United States. My parents, like theirs, were at home in Korea. None knew about my relationship with Sun Myung Moon. None knew I was a wife and a mother. They thought I lived with a guardian in Irvington. No one asked for more information than that, and I found myself grateful for the discretion of my Korean culture.

One girl at Masters School was especially sweet. She was younger than I and treated me like a big sister. When she needed a confidante, I was happy to fill that role. She could not bear to speak to her mother when her family telephoned from Seoul. Just the sound of her mother’s voice would make her weep with homesickness.

I felt so sorry for her, but I envied her, too. It only occurred to me in comforting her that I did not experience the normal range of emotions of a girl my age. If I missed my mother or my family, I felt I was failing God. If I longed to go home, I felt I was resisting my fate. If I hated my husband, I felt I was doubting the wisdom of Sun Myung Moon.

I was free to feel my failure and my loneliness, but I was not free to express them. As a result, my friendships with classmates were strictly superficial, one-way propositions. I could not confide in anyone that school year when I realized I had suffered a miscarriage.

I had known for weeks that I was pregnant but had missed my first doctor’s appointment. When I began to notice small amounts of blood staining my panties, I did not think much of it. When an ultrasound confirmed that I had lost the baby, I was devastated. I had to be hospitalized overnight for a D and C. Hyo Jin did not come to see me until it was all over. He found me weeping in my hospital room. Instead of comforting me, he said my tears disgusted him. He cared less that we had lost our baby than that I was making a scene. “You are very unattractive when you cry,” he said, before leaving me alone with my loss.

I wished, then, that I had a real friend, but I knew that my life and the lives of the girls I sat alongside in the schoolroom were alike only on the surface. If I was going to survive in the True Family, I realized after Hyo Jin’s heartless response to my miscarriage, I would need to compartmentalize my emotions even more than I had already done.

More than most young women my age, I was suspended between childhood and adulthood, with a foot in both worlds. I was still young and dependent enough that spring to ask my mother to pick out the long white dress I would wear to my high school graduation. I was also old enough to have a toddler at home, watching me get ready for the ceremony, where then-Vice President George Bush would give the commencement address at the request of his godchild, one of my classmates.

“Can I come, Mommy?” my daughter wanted to know. I longed to have my little girl with me on my big day, but I left her at home in East Garden. I had not figured out how to integrate the two very different worlds in which I lived.

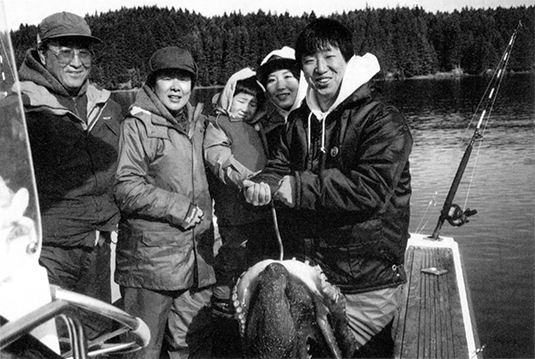

▲ Hyo Jin Moon hauls an octopus aboard True Father’s fishing boat off Kodiak, Alaska, where Sun Myung Moon maintains one of his many homes. From left to right: Sun Myung Moon, Hak Ja Han Moon, me (holding our son Shin Gil), and Hyo Jin.

Chapter 7

page 133

December 22, 1983, dawned cold and damp in the Hudson River valley. The gloomy weather reflected the mood at East Garden. Father and Mother had left days before for a major speaking tour in Korea. The Reverend Moon was scheduled to address a rally in Chonju, South Korea, an anti-government stronghold. There were fears for his safety because of his close ties to the repressive military regime of Chun-Doo Hwan.

He had to go into the camp of the enemy. Father told us, because only by direct confrontation could he defeat the Communists, Satan’s emissaries on earth. We thought Sun Myung Moon was the bravest man in the world. The prayer ladies spent the day at Holy Rock, praying for a successful and peaceful trip.

The link between religion and politics had been explicit for Sun Myung Moon since his childhood in Japanese-occupied Korea. The division of our country into Communist and democratic zones had further defined the lines of political demarcation for his religious ministry. The Communists had imprisoned him as an itinerant preacher. They had outlawed religious pluralism. They were the enemy. He devoted his public life to the spread of Unificationism and the defeat of Communism. For Sun Myung Moon one goal was inseparable from the other.

If Hyo Jin was concerned about his parents, there was no change in his behavior to indicate it. Early that evening he went into New York to visit the bars. I was at home alone with the baby when the telephone rang after midnight. It was one of the security guards. “There’s been an accident,” he said. I feared immediately for True Parents. “No, it’s not Father,” he said. “It’s Heung Jin.”

Heung Jin?

The second son of the Reverend and Mrs. Moon had been driving home from a night out with two Blessed Children when his car slammed into a disabled truck on an icy road not far from the Unification Theological Seminary in Barrytown, New York. Heung Jin and his friends often went to the seminary to use the firing range that the Reverend Moon’s sons, all avid hunters, had built on the grounds. All three boys were hospitalized.

My brother, Peter Kim, and I rushed directly to the emergency room at St. Francis Hospital in Poughkeepsie, New York. None of us was prepared for what we found. Jin-Bok Lee and Jin-Gil Lee were injured, but not seriously. However, Heung Jin had suffered severe head trauma in the crash. He was in the operating room undergoing brain surgery when we arrived.

I watched Peter Kim walk to the pay phone in the corridor to call Father and Mother in Korea. He was weeping. “Forgive me. I am so unworthy,” he began. “You left me in charge of your family and the most terrible thing has happened.” The call did not last long. The Reverend and Mrs. Moon said they would be on the next plane home.

I had never been exposed to serious illness or life-threatening injury before. It was terrifying to see a boy my own age, especially a boy as sweet as Heung Jin, lying in an intensive care unit, attached to all manner of tubes and machines. He was unconscious. He lay perfectly still, the only sound the hum of the respirator that pumped oxygen into his inert body. We did not need a doctor to tell us the gravity of his condition.

We all went to New York to meet True Parents at the airport the next day. I’ll never forget the stricken look on Mrs. Moon’s ashen face. It was clear she had not slept since receiving Peter Kim’s call. We followed the Moons to the hospital, where church members had all but taken over the ICU waiting room and were conducting a prayer vigil for Heung Jin.

The Reverend Moon concentrated on comforting everyone else before he entered Heung Jin’s room. Mrs. Moon wanted only to be with her son. There would be no miracle. Heung Jin was brain dead. On January 2, 1984, the Moons made what must have been the hardest decision of their lives. With all of us gathered around his hospital bed, the ventilator that kept seventeen-year-old Heung Jin Moon alive was turned off. He died without ever regaining consciousness. Mrs. Moon clung to her son’s lifeless body, her tears staining the crisp white bed linens. The Reverend Moon stood dry-eyed beside her, trying to console a mother who was beyond consolation.

The rest of us wept copious tears at the death of our brother, but the Reverend Moon ordered us not to cry for Heung Jin; he had gone to the spirit world to join God. We would be reunited with him one day. We all remarked with admiration on Father’s strength, on his ability to put his love of God before the loss of his son. As a new mother, I was more mystified than impressed by Sun Myung Moon’s reaction.

There was an enormous funeral for Heung Jin at Belvedere. At Mrs. Moon’s instruction, the women and girls in the family wore white dresses; the men wore white ties with their black suits. Church members wore their white church robes. Upstairs as we got ready for the service, I felt my usual awkwardness. I was not a True Child, just an in-law, so I did not know quite where I belonged. I found my place at the edge of the family. The kitchen sisters had prepared all of Heung Jin’s favorite foods to remind us of the boy we had lost. The table looked as if it had been laid out for a teenager’s birthday party: hamburgers, pizza, and Coca-Cola.

I had never been to a funeral before. Heung Jin’s open coffin was placed in the living room. It was a large room, but overflowing with two hundred people, it soon grew very hot. For three hours, friends and family offered testimonials to Heung Jin, to his goodness and his kindness. I wept openly, despite my promise to Father not to cry. I was not alone. The Reverend Moon instructed all members of the True Family to kiss Heung Jin good-bye. The littlest ones understandably were frightened. I lifted some of the smallest to kiss Heung Jin’s cheek, as I did myself. He was so terribly cold.

Father walked to the front of the room and instantly all sounds of weeping ceased. He told the funeral gathering that Heung Jin was now the leader of the spirit world. His death had been a sacrificial one. Satan was attacking the Reverend Moon for his anti-Communist crusade by claiming the life of his second son. Like Abel before him, Heung Jin had been the good son. Hyo Jin looked wounded by Father’s comparison, but he knew himself that he bore more of a resemblance to the Biblical Cain.

Heung Jin, Father said, was already teaching those in the spirit world the Divine Principle. Jesus himself was so impressed by Heung Jin that he had stepped down from his position and proclaimed the son of Sun Myung Moon the King of Heaven. Father explained that Heung Jin’s status was that of a regent. He would sit on the throne of Heaven until the arrival of the Messiah, Sun Myung Moon.

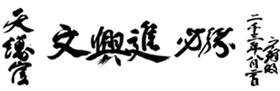

▲ Sun Myung Moon wrote this calligraphy which declared that

▲ Sun Myung Moon wrote this calligraphy which declared that

Heung Jin Moon 文興進 was the commander-in-chief of Heaven.

I was stunned by the instant deification of this teenage boy. I knew Heung Jin was a True Child, the son of the Lord of the Second Advent, so I was ready to believe that he had a special place in Heaven. But displacing Jesus? The boy I had helped search for a lost kitten in the attic of the mansion at East Garden, he was the King of Heaven? It was too much, even for a true believer like myself. I looked around me, though, and the assembled relatives and guests were nodding gravely at this imparted revelation. I was ashamed of my skepticism but powerless to deny it.

Heung Jin’s coffin was carried out to the hearse and driven to JFK International Airport for the long flight to Korea. The Reverend and Mrs. Moon did not accompany their son’s body. Je Jin and Hyo Jin went home with their brother. Heung Jin was buried in a Moon family plot in a cemetery an hour outside of Seoul.

Almost immediately, videotapes began arriving at East Garden from around the world. Unification Church members in various states of entrancement were pronouncing themselves the medium through which Heung Jin spoke from the spirit world. It was so strange to watch these tapes. We would gather with Father and Mother around the television and watch one stranger after another purport to speak for Heung Jin. None of them offered any profound religious insights. None displayed any confirming familiarity with Heung Jin’s life in East Garden. But all praised True Parents and reinforced Father’s revelation that Jesus had bowed down to Heung Jin in Heaven.

I not only did not believe the claims in these tapes, I was offended that so many people would try to exploit the grief of the True Family in such a transparent attempt to gain favor with Father. I was naive. This was exactly the approach most likely to win Sun Myung Moon’s affection. Father clearly was thrilled by this “possession” phenomenon, occurring spontaneously around the globe. It was impossible for me to tell whether the Reverend Moon actually believed his son was speaking through these people or if he was using their scam for his own purposes.

One theological problem with the deification of Heung Jin Moon was that Sun Myung Moon teaches that the Kingdom of Heaven is attainable only by married couples, not by single individuals. Father dealt with that expeditiously. Less than two months after Heung Jin died, a wedding ceremony was held in which Sun Myung Moon joined his dead son in marriage to Hoon Sook Pak, the daughter of Bo Hi Pak, one of his original disciples. Hoon Sook’s brother, Jin Sung Pak, was married on the same day to In Jin Moon. The joint wedding on February 20, 1984, can only be described as bizarre.

In Jin was furious that Father had matched her to Jin Sung, a boy she could not stand. In Jin had many boyfriends; marriage was the last thing on her mind. She called Jin Sung “fish eyes,” after the most distinctive physical characteristic of the Pak family. The truth was she had a crush on a younger boy. The year before, In Jin and I had shared a room in a Washington, D.C., hotel, where we were attending a Unification Church conference. She thought I was sleeping late one night when she telephoned this boy at his family’s Virginia home. She was whispering softly and giggling in a girlish way that was unlike her in my experience. I realized she was flirting with him, telling him that even though Blessed Children were not supposed to kiss, she thought they could make an exception.

It was a dangerous infatuation. What neither of them knew at the time was that they shared the same father. The boy is Sun Myung Moon’s illegitimate son. My mother had told me so a year before, but it was clear to me that night that no one had told them. That the boy had been born of an affair between the Reverend Moon and a church member was an open secret among the thirty-six Blessed Couples. It was not a romantic liaison, my mother had explained to me. It was a “providential” union, ordained by God, but one that the secular world would not understand. To avoid any misunderstanding, the baby was placed at birth with the family of one of Sun Myung Moon’s most trusted advisers and was raised as his son. His real mother lived nearby in Virginia and played the role of family friend in his young life. The Reverend Moon has never acknowledged his paternity publicly, but by the late 1980s, the boy and the second generation of Moons were told the truth.

The placement of a baby in the home of an unrelated church member was not an isolated occurrence. It happened all the time. Infertile couples in the church simply were given a baby by members who had several children. Since we all belonged to the family of man and the only True Parents are the Reverend and Mrs. Moon, what difference did it make who actually reared a child? The Unification Church often dispensed with such legal niceties as adoption proceedings and simply shared out children in much the way one neighbor might lend another an extra garden hose.

We had gathered at the Belvedere mansion for the double wedding that February just as we had for my own two years before. In their white ceremonial robes, the Reverend and Mrs. Moon presided first over the wedding of their daughter In Jin to Jin Sung Pak. Immediately following the ceremony, the crowd fell silent as Hoon Sook entered the ornate library in a formal white wedding gown and veil. A beautiful young woman, she was twenty-one, an aspiring ballerina. The Reverend Moon would found the Universal Ballet Company in Korea to highlight her talent under the stage name Julia Moon.

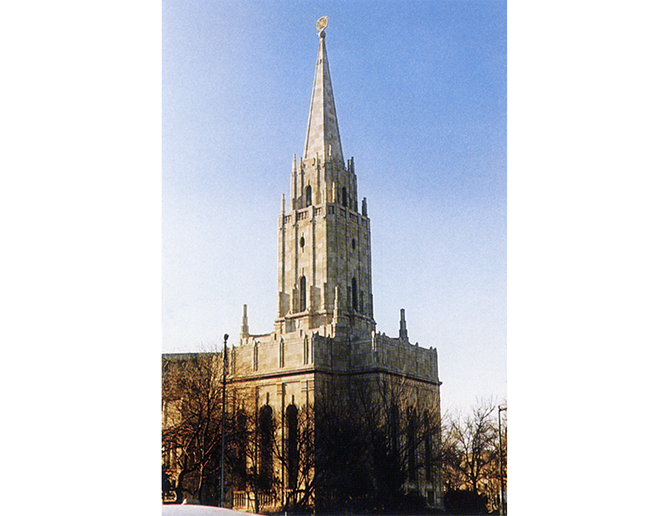

▲ The wedding of Hoon Sook Pak to the dead Heung Jin Moon.

She carried a framed portrait of Heung Jin down the aisle to Mother and Father. My husband, Hyo Jin, stood in for his dead brother next to the bride. He repeated the vows that Heung Jin was not able to recite. Hoon Sook was such a beautiful bride, I felt sorry that she would never be able to marry a living groom. But as my eyes moved from her to Hyo Jin, I felt something else stirring in me; it was envy. How much better, I thought, to be loved by a dead man than to live in misery with a man you do not love and who does not love you.

This ceremony would have seemed strange, indeed, to anyone outside the Unification Church, but the Reverend Moon frequently joined the living with the dead in matrimony. Older, single members were often matched to members who had gone to the spirit world. In what must stand as his ultimate act of arrogance, Sun Myung Moon actually had matched Jesus to an elderly Korean woman. Because the Unification Church teaches that only married couples can enter the Kingdom of Heaven, Jesus himself needed the intervention of the Reverend Moon to move through those gates.

A few years after their Holy Wedding, Julia Moon and the long-dead Heung Jin Moon would become parents. She did not actually give birth, of course. Heung Jin’s younger brother Hyun Jin and his wife simply gave Julia their newborn son. Shin Chul, to raise as her own.

The civil authorities were unaware of these allegedly miraculous doings, however. Four months after Heung Jin’s death, the U.S. Supreme Court, without comment, refused to review the Reverend Moon’s conviction for federal tax evasion. Sixteen amici curiae briefs filed by organizations such as the National Council of Churches, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference portrayed the case as one of religious persecution with profound implications for the free exercise of religion. If Sun Myung Moon could be targeted, the thinking went, what unpopular evangelist might be next?

“The precedent has been set for the government to examine the internal finances of any religious organization,” warned the Reverend George Marshall of the Unitarian-Universalist Association.

The Reverend Mr. Marshall was one of four hundred religious leaders around the nation who spoke up in support of Moon in rallies staged across the country. The Reverend Edward Sileven, a Baptist minister from Louisville, Nebraska, compared Moon’s plight to his own. The Reverend Mr. Sileven had served eight months in jail for refusing to obey a court order to close down his unaccredited fundamentalist Christian school. “People ask me, ‘Don’t you feel funny coming to a rally for the Reverend Moon?’ But I’d rather fight for your freedom once in a while than come together with you all in a concentration camp.”

Jeremiah S. Gutman, president of the New York Civil Liberties Union, organized an ad hoc committee of religious and civil rights leaders to protest what he called “an indefensible intrusion in private religious affairs.”

A U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee panel chaired by Senator Orrin G. Hatch reviewed the Moon case and agreed.

We accused a newcomer to our shores of criminal and intentional wrongdoing for conduct commonly engaged in by a large percentage of our own religious leaders, namely, the holding of church funds in bank accounts in their own names. Catholic priests do it. Baptist ministers do it, and so did Sun Myung Moon.

No matter how we view it, it remains a fact that we charged a non—English speaking alien with criminal tax evasion on the first tax returns he filed in this country. It appears that we didn’t give him a fair chance to understand our laws. We didn’t seek a civil penalty as an initial means of redress. We didn’t give him the benefit of the doubt. Rather we took a novel theory of tax liability of less than $10,000 and turned it into a guilty verdict and 18 months in federal prison.

I do feel strongly, after my subcommittee has carefully and objectively reviewed this case from both sides, that injustice rather than justice has been served. The Moon case sends a strong signal that if one’s views are unpopular enough, this country will find a way not to tolerate, but to convict.

The Reverend Charles V. Bergstrom of the Lutheran Council in America testified before Senator Hatch’s committee, but he was more subdued in his assessment of the Reverend Moon’s tax case. “I have a question about whether he had a fair trial. The court denied Reverend Moon’s request to have a judge decide the case, and the judge told the jury not to consider him a religious person for the purpose of the trial. But I also have to ask: Why did he have to handle all that money?”

The answer was clear enough to anyone inside the church: the Unification Church was a cash operation. I watched Japanese church leaders arrive at regular intervals at East Garden with paper bags full of money, which the Reverend Moon would either pocket or distribute to the heads of various church-owned business enterprises at his breakfast table. The Japanese had no trouble bringing the cash into the United States; they would tell customs agents that they were in America to gamble at Atlantic City.

In addition, many businesses run by the church were cash operations, including several Japanese restaurants in New York City. I saw deliveries of cash from church headquarters that went directly into the wall safe in Mrs. Moon’s closet. From here, on any given day, she might distribute five thousand dollars to the kitchen staff for food or five hundred dollars to a child who had just won a game of hopscotch.

There was no question inside the church that the Reverend Moon used his religious tax exemption as a tool for financial gain in the business world. The pursuit of profit was central to his religious philosophy. A capitalist at heart, the Reverend Moon preaches that he cannot unify the world’s religions without building a network of businesses to support believers. To that end, he has built or bought food processing plants, fishing fleets, automobile assembly lines, newspapers, companies that produce everything from machine tools to computer software.

No matter what the lawyers said in court, no one internally disputed that the Reverend Moon comingled church and business funds. No one had any problem with it. How often had I heard church advisers discuss funneling church funds into his business enterprises and political causes because his religious, business, and political goals are the same: world dominance for the Unification Church. It was U.S. tax laws that were wrong, not Sun Myung Moon. Man’s law was secondary to the Messiah’s mission.

The Reverend Moon’s philosophy sounded benign enough: “The world is fast becoming one global village. The survival and prosperity of all are dependent on a spirit of cooperation. The human race must recognize itself as one family of man.” What his civil libertarian allies outside the Unification Church failed to realize was that Sun Myung Moon, and only Sun Myung Moon, was the head of that family.

Using church funds to finance his anti-Communist political agenda was a given, part of the Unification Church philosophy. In 1980 the Reverend Moon had established CAUSA, an anti-Communist front that the church described as a “nonprofit, non-sectarian, educational and social organization which presents a God-affirming perspective of ethics and morality as a basis for free societies.” In practical terms that meant CAUSA supplied crucial funds to oppose Communist movements in El Salvador and Nicaragua.

The Reverend Moon was never shy about drawing attention to the roots of his anti-Communist beliefs. “The need for unity among the God-affirming peoples of the worlds became profoundly clear to the Reverend Moon when he was imprisoned and tortured for his Christian faith by North Korean Communists in the late 1940s. CAUSA is an outgrowth of his commitment to America and to world freedom.”

In the 1980s Latin America was the focus of the Reverend Moon’s anti-Communist zeal. The missionaries he sent to support anti-Communist sympathizers in the region did not come wearing church robes. They came in business suits, under the auspices of the many “scholarly” organizations that Father quietly established and funded without any overt reference to Sun Myung Moon or the Unification Church. With titles such as the Association for the Unity of Latin America, the International Conference on Unity in the Sciences, the Professors World Peace Academy, the Washington Institute for Values in Public Policy, the American Leadership Conference, and the International Security Council, the Reverend Moon’s missionary arms had an academic veneer. Speakers to conferences sponsored by these groups, many of them prominent figures in the media, politics, and scholarship, rarely knew that their fees, hotel rooms, and meals were being paid for by Sun Myung Moon.

Personally, the Moons had an almost physical aversion to paying taxes. Lawyers for the church spent most of their time trying to figure out how to avoid them. That’s why the True Family Trust fund was based not in a U.S. bank but in an account in Liechtenstein.

It is only in retrospect that I see the hypocrisy of Sun Myung Moon’s claiming religious persecution for his efforts to manipulate the law for his own gain. At the time, I was an impressionable teenager, a new mother, a faithful follower. That year, I returned to Korea for the first time in order to secure a more permanent visa. I had been in the United States illegally for three years before the Moons decided it was time to legitimize my immigration status. I was not alone. East Garden was full of maids, kitchen sisters, baby-sitters, and gardeners who had come into the United States on tourist visas and just melted into the subculture of the Unification Church.

I had not really understood then that we were breaking the law. It would not have mattered to me. God’s law supersedes civil law and Father was God’s representative on earth. Even the importance of the Reverend Moon’s trial the year before had escaped me. But prison? That I understood. We all were heartsick that Father would actually be locked up for a year and a half.

At 11:00 p.m. on July 20, 1984, Sun Myung Moon took up residence at the medium-security federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut. The day before surrendering to prison authorities, Father had met at the mansion in East Garden with church leaders from 120 countries. He assured them that he would simply move his base of operations from home to prison. His living accommodations would be quite different in Danbury, where he was housed in a dormitory-style building with forty or fifty other inmates. He was assigned to mop floors and clean tables in the prison cafeteria.

He was allowed visitors every other day. I dutifully accompanied Mrs. Moon in order to serve them both. I fetched food from the vending machines, slipping black extract of ginseng into cups of instant soup at Mother’s instruction to give Father extra strength during his ordeal. The leaders of his various business enterprises and church leaders came to consult with him frequently. The business of the Unification Church continued uninterrupted.

Whenever we visited Father, he would give the children homework assignments, to write a poem or an essay. We would then read them to him on a return trip. I remember one he gave me, “The Life of a Lady.”

In Jin took on the role of public defender of her father. In a rally for religious freedom in Boston, she told 350 supporters that Sun Myung Moon’s plight was similar to that of Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist. “This is a very difficult time for me to bear and understand,” she told the crowd. “In 1971 he came to this country obedient to the voice of God. For the last twelve years he has shed his tears and sweat for America. He told me God needs America to save the world. Now he is sixty-four years old and guilty of no crime. When I visited him in prison and saw him in his prison clothes, I cried and cried. He told me not to weep or be angry. He told me and millions of others who follow him to turn our anger and grief into powerful action to make this country truly free again.”

In Jin shared the stage that night with former U.S. senator Eugene McCarthy, who denounced Father’s incarceration as a threat to liberty. The Reverend Moon’s prison term was turning into a public relations coup for the Unification Church. Overnight he went from being a despised cult leader to being the symbol of religious persecution. Well-meaning civil libertarians made Sun Myung Moon a martyr to their cause. They, too, were being duped.

Shaw Divinity School in Raleigh, North Carolina, awarded an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree to Father while he was imprisoned. The school cited Sun Myung Moon for his “humanitarian contributions in several areas: social justice, efforts to relieve human suffering, religious freedom and the fight against world communism.” Joseph Page, the vice president of the school, insisted that the Unification Church’s thirty-thousand-dollar contribution to Shaw Divinity School had “absolutely not” influenced the board of trustees to honor the Reverend Moon.

While he was in prison, the Reverend Moon sent Hyo Jin to Korea to direct a special workshop for Blessed Children, the sons and daughters of original members. “Previously, each was heading in his own direction, and there was no discipline among them,” Sun Myung Moon would say later in a speech. “But now they have been brought together in a certain order. It is significant that this happened while I was serving my prison sentence because after Jesus’ crucifixion, all his disciples separated and ran away. Now, during my incarceration, the Blessed Children from around the world came together, to the central point, instead of running away.”

Even as Father was gaining respectability among mainstream Christians and consolidating his hold on the second generation of Unificationists during his time in prison, his son was growing in stature after death. Reports of messages from Heung Jin were proliferating, although some of them were less than profound: “Dear Brothers and Sisters of the Bay Area: Hi! This is the team of Heung-Jin Nim and Jesus here. We need to establish a foothold among you and bring true sunshine here to California,” read one written on official Unification Church stationery. It was purportedly transcribed by a church member while in a trancelike state.

“Our brother has received messages from Heung Jin Nim, St. Francis, St. Paul, Jesus, Mary and other spirits have come to him as well,” Young-Whi Kim, a church theologian, wrote of one such medium. “They all refer to Heung Jin Nim as the new Christ. They also call him the Youth-King of Heaven. He is the King of Heaven in the spirit world. Jesus is working with him and always accompanies him. Jesus himself says that Heung Jin Nim is the new Christ. He is the center of the spirit world now. This means he is in a higher position than Jesus.”

Back on earth, after thirteen months in prison, the Reverend Moon was freed on August 20, 1985. He was released to the cheers of his new friends in the religious community. Both the Reverend Jerry Falwell of the Moral Majority and the Reverend Joseph Lowery of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference called on President Ronald Reagan to grant Father a full pardon. Two thousand clergymen, including Falwell, Lowery, and other well-known religious leaders, held a “God and Freedom Banquet” in his honor in Washington, D.C.

At East Garden it was as though Father had returned from a world speaking tour and not from a prison term. The old rhythms returned. The meetings around his breakfast table resumed. But something was different. There was a perceptible shift in the Reverend Moon’s Sunday-morning sermons at Belvedere after his release from the penitentiary. He talked less and less about God and more and more about himself. He seemed obsessed with his vision of himself as some kind of historical figure, not merely as an emissary of God. Where once I had listened intently to his sermons in search of spiritual insight, I now found myself more uneasy and less engaged.

The Reverend Moon’s hubris culminated later that year in a secret ceremony in which he actually crowned himself and Hak Ja Han Moon as Emperor and Empress of the Universe. Preparations for the lavish, clandestine event at Belvedere took months and hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Church women were assigned to research the regal robes of the five-hundred-year Yi dynasty that ended in the nineteenth century. Others were ordered to design solid-gold-and-jade crowns modeled on the ones worn by tribal kings. My mother was in charge of buying yards and yards of silk and satin and brocade material and finding seamstresses in Korea to turn these expensive raw materials into the costumes of a royal court. All twelve of Sun Myung Moon’s children, all of his in-laws, all of his grandchildren, were to be outfitted as princes and princesses.

In the end Sun Myung Moon’s crowning ceremony looked less like a historical reconstruction than like a popular Korean television soap opera set during the Yi dynasty. I felt silly, as though I were dressed for a period comedy rather than a sacred religious service. The Reverend Moon was aware enough of how an act of such monumental egotism would be received by the world that he banned photographs from being taken at the actual ceremony. Invited guests, all high-level church officials, who arrived with cameras had them confiscated by security guards, who blocked the entrances to gate-crashers.

In his gold crown and elaborate robes, Sun Myung Moon looked to me for all the world like a modern-day Charlemagne. The difference was that this emperor bowed to no pope. Since there was no authority higher than the Reverend Moon, the Messiah had to crown himself Emperor of the Universe.

The coronation was a turning point for me and my parents. For the first time we voiced our doubts to one another about Sun Myung Moon. It was not an easy thing to do. Much has been written about the coercion and brainwashing that takes place in the Unification Church. What I experienced was conditioning. You are isolated among like-minded people. You are bombarded with messages elevating obedience above critical thinking. Your belief system is reinforced at every turn. You become invested in those beliefs the longer you are associated with the church. After ten years, after twenty years, who would want to admit, even to herself, that her beliefs were built on sand?

I didn’t, surely. I was part of the inner circle. I had seen enough kindness in the Reverend Moon to excuse his blatant lapses — his toleration of his son’s behavior, his hitting his children, his verbal abuse of me. Not to excuse him was to open my whole life up to question. Not just my life. My parents had spent thirty years pushing aside their own doubts. My father tolerated the arbitrary way in which Sun Myung Moon ran his businesses, inserting unqualified friends and relatives into positions of authority, promoting those who curried favor and firing those who displayed any independence. My father survived at the top of Il Hwa pharmaceuticals by accepting the Reverend Moon’s frequent public humiliations. For his part, the Reverend Moon left my father in place because Il Hwa continued to make money for him.

If the deification of Heung Jin and the crowning ceremony tested my faith, the emergence of the Black Heung Jin nearly destroyed it. Many of the reports of possession by Sun Myung Moon’s dead son came from Africa. In 1987 the Reverend Chung-Hwan Kwak went to investigate reports that Heung Jin had taken over the body of a Zimbabwean man and was speaking through him. The Reverend Kwak returned to East Garden professing certainty that the possession was real. We all gathered around the dinner table to hear his impressions.

The Zimbabwean was older that Heung Jin, so he could not be the reincarnated son of Sun Myung Moon. In addition, the Unification Church rejects the theory of reincarnation. Instead, the African presented himself to the Reverend Kwak as the physical embodiment of Heung Jin’s spirit. The Reverend Kwak had asked him what it was like to enter the spirit world. The Black Heung Jin said that upon entering the Kingdom of Heaven, he immediately became all-knowing. The True Family need not study on earth because they were already perfected. Knowledge would be theirs when they entered the spirit world.

That rationale appealed to Hyo Jin as much as if offended me. He had flirted with some courses at Pace University and at the Unification Church seminary in Barrytown, New York, but my husband was more interested in drinking than in learning. I was put off by the suggestion that we did not have to work to earn God’s favor. We in the Unification Church might be God’s chosen people, but I believed our efforts on earth would determine our place in the afterlife. We had to earn our place in Heaven.

The Reverend Moon was thrilled with the news from Africa. The Unification Church had been concentrating its recruitment efforts in Latin America and Africa. Clearly a Black Heung Jin could not hurt the cause. Without even meeting the man who claimed to be possessed by the spirit of his dead child, Sun Myung Moon authorized the Black Heung Jin to travel the world, preaching and hearing the confessions of The Unification Church members who had gone astray.

▲ Black Heung Jin at the New Yorker Hotel

Confessions soon became central to the Black Heung Jin’s mission. He went to Europe, to Korea, to Japan, everywhere administering beatings to those who had violated church teachings by using alcohol and drugs or engaging in premarital sex. The Black Heung Jin spent a year on the road, dispensing physical punishment as penance for those who wished to repent, before Sun Myung Moon summoned him to East Garden.

We all gathered to greet him at Father’s breakfast table. He was a thin black man of average height who spoke English better than Sun Myung Moon. He seemed to me intent on charming the True Family, in much the way a snake encircles and then swallows its prey. I was anxious to hear some concrete evidence that this man possessed the spirit of the boy I once knew. I was not to hear it. The Reverend Moon asked him standard theological questions that any member who had studied the Divine Principle could have answered. He offered no startling revelations or religious insights. Maybe what most impressed Father was his ability to quote from the speeches of Sun Myung Moon.

▲ From left to right: Sun Myung Moon, Black Heung Jin

(Cleopas Kundiona) and Hak Ja Han Moon in 1988.

The Reverend and Mrs. Moon suggested that we children meet with the Black Heung Jin privately and report back to them on our impressions. It was an amazing meeting. Hyun Jin, Kook Jin, and Hyo Jin kept asking the stranger questions about their childhood. He could not answer any of them. He did not remember anything about his life on Earth, he told us. Instead of inspiring skepticism, the Black Heung Jin’s convenient memory loss was interpreted as a sign of his having left earthly concerns behind when he entered the Kingdom of Heaven. Everyone in the household embraced him and called him by their dead brother’s name. I avoided him and found myself thinking that I was living with either the stupidest or the most gullible people on earth. There was a third alternative I did not consider at the time: the Reverend Moon was using the Black Heung Jin for his own ends, just as he had used the American civil liberties community before him.

Sun Myung Moon seemed to take pleasure in the reports that filtered back to East Garden of the beatings being administered by the Black Heung Jin. He would laugh raucously if someone out of favor had been dealt an especially hard blow. No one outside the True Family was immune from the beatings. Leaders around the world tried to use their influence to be exempted from the Black Heung Jin’s confessional. My own father appealed in vain to the Reverend Kwak to avoid having to attend such a session.

The Black Heung Jin was a passing phenomenon in the Unification Church. Soon the mistresses he acquired were so numerous and the beatings he administered so severe that members began to complain. Mrs. Moon’s maid, Won Ju McDevitt, a Korean who married an American church member, appeared one morning with a blackened eye and covered with purple bruises. The Black Heung Jin had beaten her with a chair. He beat Bo Hi Pak – a man in his sixties – so badly that he was hospitalized for a week in Georgetown Hospital. He told doctors he had fallen down a flight of stairs. He later needed surgery to repair a blood vessel in his head.

Sun Myung Moon knew when to cut his losses. When you are the Messiah, it is easy to make a course correction. Once it became clear that he had to disassociate himself from the violence he had let loose on the membership, Sun Myung Moon simply announced that Heung Jin’s spirit had left the Zimbabwean’s body and ascended into Heaven. The Zimbabwean was not quite so ready to get off the gravy train. At last sighting, he had established a breakaway cult in Africa with himself in the role of Messiah.

▲ Sun Myung Moon liked to keep a heavy wooden stick ready, as seen above in this mid-1960s photo. There was violence hidden at the heart of his church.

See footnote below for one eye-witness account of Black Heung Jin’s violence.

Chapter 8

page 154

I had just taken my last spring final exam at New York University when Hyo Jin called from Korea in May 1986. He had been in Seoul for weeks. He missed me and the baby, he said. We should come as soon as possible.

It was my first year in college. The Moons had been willing to send me on the theory that my academic success would reflect well on them one day. I had been up late every night for days, studying for finals and writing term papers. I wanted to do well, not only to justify the expense of my education to the Reverend and Mrs. Moon but to feel pride in my freshman accomplishments.

The classroom was the one place in my universe over which I felt complete mastery. I knew how to learn, how to study, how to take tests. I did not know how to think critically, but I rarely had to in order to earn good grades. The memorization skills I had learned as a child in Korea were serving me well in American higher education as well.

New York University had not been my first college choice. I wanted to attend Barnard College, the women’s undergraduate division of Columbia University. I knew it was one of the prestigious Seven Sisters schools and I felt reassured that my classmates would be females. I was married and a mother but still as awkward as an adolescent girl around young men.

Barnard would not have me. I had foolishly applied as an early-decision candidate, a realistic option for only the very best students. My grades were good but my essays showed the lack of self-reflection that characterized my life at that time. I was determined after that initial rejection to do so well at N.Y.U. that Barnard would reconsider and accept me as a transfer student one day.

I was also in my first trimester of a new pregnancy when Hyo Jin summoned me to Seoul, and the prospect of the long flight with a toddler could not have been less appealing. I was worried, too, about the chance of miscarriage after my last, failed pregnancy. But it was so rare for Hyo Jin even to call me when he was away, let alone to request my company, that I eagerly interpreted this as a hopeful sign for our marriage.

The flight was every bit as grueling as I had feared. My daughter was too excited to sleep. She shook me every time I closed my eyes. I kept myself awake with optimistic thoughts of how God must have used this time to soften Hyo Jin’s heart.