Updated April 23, 2021 – under construction

Sun Myung Moon: “split the person apart”

Significance Of The Training Session

Reverend Sun Myung Moon

Third Directors’ Conference

Master Speaks May 17, 1973 Translated by Mrs. Won-bok Choi

“Good morning! Sit down!

I am going to speak about the significance of a training session like this. Master’s intention is to have the State Representatives, Commanders, and the Itinerary Workers pass the examination, getting at least 70 points. I will continue this until the last one of the responsible members has passed the examination.

For fallen men it is their duty to pass through three stages of judgment! Judgment of words, judgment of personality, and judgment of love or heart. All through history, mankind has been in search of the truth, true words. The truth is the standard by which all the problems of mankind can be solved. We know man somehow fell in the beginning, and to fall means to fall into the bondage of Satan. So, in order for us to return to the original position, we have to get rid of the bondage of Satan. For fallen people, there is no other message which is more hopeful and desirable than the message of restoration to the original position, To be restored is, in another sense, to be liberated from Satanic bondage – and this is the gospel of gospels for fallen men.

Then what is judgment? Judgment is the measurement of the standard on which all our acts are judged. If our acts cannot come in accordance with the original rule or measurement, we must be judged or punished.

…

Through 40 days you will have six cycles of Divine Principle lectures. If you study hard, after the sixth cycle of lectures – or in the course of them – you can imagine what will come next when the lecturer gives you a certain chapter. You can even analyze or criticize President Kim’s lecture. You may think, “The last time I came he gave a dynamic lecture, but he is tired this time; when I give the lecture I will never be tired,” etc. In your own way, you can organize your lecture. In order for you to be a dynamic lecturer, you must know the knack of holding and possessing the listeners’ hearts. If there appears a crack in the man’s personality, you wedge in a chisel, and split the person apart. For the first few lectures, you will just memorize. But after that, you will study the character of your audience, and adapt your lecture. If he is a scientist, you will approach him differently than a commercial man, artist, etc. The audience as a whole will have a nature, and you must be flexible.

At least two weeks – you must experience flower selling – two weeks to 30 days. Whether in two weeks or in one full month, until you raise 80 dollars a day; then you go to rallies, witnessing, and then if you cannot bring in three persons in one month’s time, you cannot go. That’s the formula you have to go through….”

http://www.tparents.org/moon-talks/sunmyungmoon73/SM730517.htm

CONTENTS

1. VIDEO: Why do people join cults? – Janja Lalich

2. PODCAST: The Cult Vault – Introduction to the Study of Cults

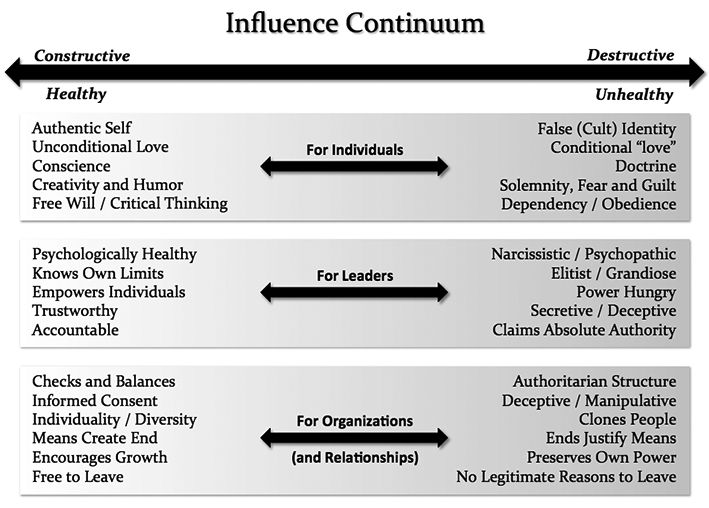

3. VIDEO: The BITE model of Steve Hassan / The Influence Continuum

4. Father Kent Burtner on manipulation of the emotions by the UC

5. VIDEO: Terror, Love and Brainwashing ft. Alexandra Stein

6. Robert Jay Lifton’s Eight Criteria of Thought Reform

7. VIDEO: The Wrong Way Home

An analysis of Dr Arthur J. Deikman’s book on cult behavior

8. Cult Indoctrination through Psychological Manipulation by Professor Kimiaki Nishida

9. Towards a Demystified and Disinterested Scientific Theory of Brainwashing by Benjamin Zablocki [This item has been expanded and moved HERE ]

10. Psyching Out the Cults’ Collective Mania by Louis Jolyon West and Richard Delgado

11. Book: Take Back Your Life by Janja Lalich and Madeleine Tobias (2009)

12. VIDEO: Paul Morantz on Cults, Thought Reform, Coercive Persuasion and Confession

13. PODCAST: Ford Greene, Attorney and former UC member, on Sun Myung Moon

14. VIDEO: Steve Hassan interviewed by Chris Shelton

15. VIDEO: Conformity by TheraminTrees

16. VIDEO: Instruction Manual for Life by TheraminTrees

17. The Social Organization of Recruitment in the Unification Church – PDF by David Frank Taylor, M.A., July 1978, Sociology

18. Mind Control: Psychological Reality Or Mindless Rhetoric? by Philip G. Zimbardo, Ph.D., President, American Psychological Association

19. Socialization techniques through which Moon church members were able to influence by Geri-Ann Galanti, Ph.D.

20. VIDEO: Recovery from RTS (Religious Trauma Syndrome) by Marlene Winell

21. VIDEO: ICSA – After the cult

22. “How do you know I’m not the world’s worst con man or swindler?” – Sun Myung Moon

23. VIDEO: What Is A Cult? CuriosityStream

24. VIDEO: The Space Between Self-Esteem and Self Compassion: Kristin Neff

25. Bibliography

1. VIDEO: Why do people join cults?

2. PODCAST: The Cult Vault – Introduction to the Study of Cults

This episode is an introduction to myself, Kaycee, and this podcast. An excellent look at the definition of a cult, and what makes some of them harmful.

3. VIDEO: The B.I.T.E. model by Steven Hassan

4. Father Kent Burtner on manipulation of the emotions by the Unification Church / FFWPU of Sun Myung Moon and Hak Ja Han

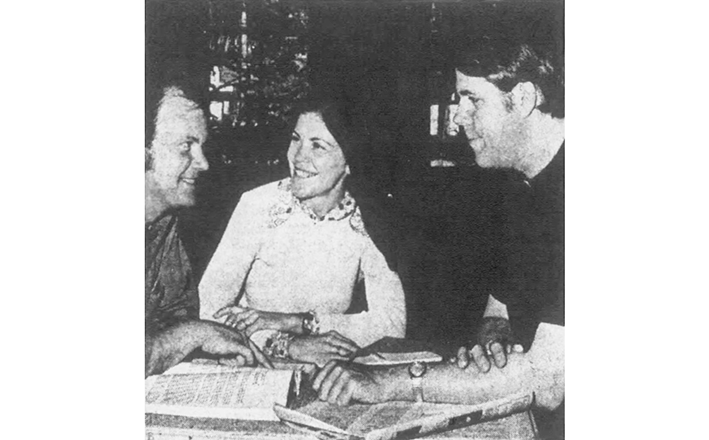

▲ Father Kent Burtner, right, discusses Rev. Sun Myung Moon and his teaching with two former Moon followers. Burtner, a Catholic priest in Eugene, Oregon, has helped “deprogram” many Moonies over decades.

By Dave Horsman – South Idaho Press Writer

There’s no universal formula for “deprogramming” a Moonie, according to Fr. Kent Burtner, a Catholic priest who first tangled with the Unification Church in 1969.

“The thing that’s crucial is that you consider who you’re talking to. You have to meet him where he’s at,” he said. In young Milton Esquibel’s case, “the process (of withdrawing from his Moonie experience) had already begun because he had so much time to spend with his family. Our time spent with him was to help reinforce the rehabilitation of his emotional faculties.”

Esquibel attended an all-day deprogramming session December 17 in Portland. It had been nearly a month since his parents abducted him from a Moonie group in Los Angeles and brought him home.

“Once they are out of the cult, their emotional life is restored to them rather dramatically,” Burtner said. “In cases where we begin deprogramming soon after the person is brought home, that restoration happens very, very suddenly.”

Burtner currently works at the Newman Center on the University of Oregon campus at Eugene. He previously was in the campus ministry at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California, where his reputation as an expert on the Unification Church was earned.

His introduction to the sect was in 1969 during his seminary training. “A daughter of our secretary got involved and I was asked to meet with her. She invited me to come to a lecture series in Berkeley. I could see then that the process by which the people got involved was much more significant than the doctrine.”

The American movement was in its infancy then. “It wasn’t until 1972 that they began the series of weekend seminars and 21-day workshops” that Esquibel attended.

Burtner has since helped dozens of young people shed the “emotional amnesia” produced by Unification indoctrination. He prefers “not to work in any extra-legal way —I don’t believe in kidnapping people.”

Gus and Gladys Esquibel, however, were “acting under the law” when they retrieved their 15-year-old son.

The “marvelous thing about deprogramming is that Moonies are led to believe it includes a variety of tortures,” he said, “when in fact we just sit down and talk. We offer a supportive environment, usually with the family and close friends present.”

Deprogramming “can be done a lot of different ways,” he added. But it usually “gives an individual a chance to look at the aspects of his life in the cult that he wasn’t able to examine when he was in it. We give the person an opportunity to see new information that the cult itself would not have divulged. And it undoes two things that have been done to the individual. The first thing is that their critical faculties (their ability to observe and assess) have been put into a state of ‘suspended animation.’ The second thing is that they are made to feel guilty for having emotions.”

Burtner explained the latter condition: “Their feelings are things that appear to them as being evil or in some way the cause of their fallen condition. That gives the cult the power to control the person. It results in a repression of the emotional life and an inappropriate sense of responsibility for the state of the world. Once they have gotten into that mind set, everything outside the group appears to be evil and Satanic and everything on the inside is where God is. So their parents and their old friends are perceived to be agents of Satan.”

“We’re talking about a systematic program that denies a person his individual freedom without his being aware of it,” Burtner said. “I don’t believe there’s anything in the (Unification Church) that essentially relates to religious commitment. It uses very, very high pressure techniques of coercion and basically places the person in a conditioned neurotic state. When you get the person out of that environment and help them see what was going on, their attachment vanishes.”

Even the diet of Moonies is part of their conditioning, according to Burtner. They get very little protein and “without at least 70 grams of protein per day the cerebral cortex is unable to function adequately. They can’t reason normally.”

People who have been Moonies only a short time often are harder to deprogram according to Burtner. “They have a real idealism, They haven’t realized they are going to spend all of their time either fundraising or recruiting new members.”

Esquibel, although he was with the Moonies only about a month, responded well in the December 17 session.

“A young woman and myself chatted with him over coffee and tea to start with. We got him to talk about his experience and we shared some of our own experiences and helped him to understand some of what he had encountered. Later on he started asking the questions. He had to have time to kind of reestablish his emotional contacts and start living his real existence again.”

Each person is different, Burtner said. “Sometimes he is quite belligerent and you have to state your case quite boldly in the beginning.”

He offers the following advice to young people who may be drawn to the Moonies: “First, learn to accept and deal with your emotional life. Second, remember you have the right to ask a lot of questions when someone wants you to get involved.”

He suggests that parents “maintain open, honest lines of communication. If there are difficulties in the family, deal with them in a straightforward way.”

While Burtner despises the Unification movement, he respects its power. He encourages people to examine the church first hand, but asks them to leave a written statement with the police allowing them “to come and get you after a week” Granting another person power of attorney to assure your return is another possibility, he added.

“I had a case like that in Eugene, involving a young woman who wanted to visit a Moonie camp. She was against the (church) after seeing what one of her friends who had been involved had gone through” and wanted to expose its practices.

“She gave me power of attorney and I had to use it after she had been there one weekend. I called (the church) and threatened to turn the story over to the Associated Press if she didn’t come home to talk to me. She returned and went through a day of deprogramming.”

5. VIDEO: Terror, Love and Brainwashing ft. Alexandra Stein

Sensibly Speaking Podcast with Chris Shelton #154

This week I have Dr. Alexandra Stein, social psychologist and author of the book Terror, Love and Brainwashing. We discuss various aspects of cult behavior and psychology.

Comments:

1. This is an outstanding piece of work that I will go back to several times. It has provided me with a degree of clarity hitherto unknown. Now, what do I do with it?

2. Some brilliant information, again, thank you. I found the part about separating from ones emotions and not allowing yourself to process them particularly interesting. Having been brought up in a [cult] family, I still struggle with dealing with (“low tone”) emotions.

6. Robert Jay Lifton’s Eight Criteria of Thought Reform

“I wish to suggest a set of criteria against which any environment may be judged — a basis for answering the ever-recurring question: “Isn’t this just like ‘brainwashing’?”

– Robert Jay Lifton

“Ideological Totalism” is Chapter 22 of Robert Jay Lifton’s book, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of ‘brainwashing’ in China

Dr. Lifton, a psychiatrist and author, has studied the psychology of extremism for decades. He is renowned for his studies of the psychological causes and effects of war and political violence and for his theory of thought reform. Lifton testified at the 1976 bank robbery trial of Patty Hearst about the theory of “coercive persuasion.”

His theories — including the often-referred to 8 criteria described below — are used and expanded upon by many cult experts.

First published in 1961, his book was reprinted in 1989 by the University of North Carolina Press. From Chapter 22:

8 CRITERIA AGAINST WHICH ANY ENVIRONMENT MAY BE JUDGED:

- Milieu Control – The control of information and communication.

- Mystical Manipulation – The manipulation of experiences that appear spontaneous but in fact were planned and orchestrated.

- The Demand for Purity – The world is viewed as black and white and the members are constantly exhorted to conform to the ideology of the group and strive for perfection.

- The Cult of Confession – Sins, as defined by the group, are to be confessed either to a personal monitor or publicly to the group.

- The Sacred Science – The group’s doctrine or ideology is considered to be the ultimate Truth, beyond all questioning or dispute.

- Loading the Language – The group interprets or uses words and phrases in new ways so that often the outside world does not understand.

- Doctrine over person – The member’s personal experiences are subordinated to the sacred science and any contrary experiences must be denied or reinterpreted to fit the ideology of the group.

- The Dispensing of existence – The group has the prerogative to decide who has the right to exist and who does not.

Eight Conditions of Thought Reform

as presented in

Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism, Chapter 22.

1. Milieu Control

The most basic feature of the thought reform environment, the psychological current upon which all else depends, is the control of human communication. Through this milieu control the totalist environment seeks to establish domain over not only the individual’s communication with the outside (all that he sees and hears, reads and writes, experiences, and expresses), but also — in its penetration of his inner life — over what we may speak of as his communication with himself. It creates an atmosphere uncomfortably reminiscent of George Orwell’s 1984…. (Page 420.)

Purposeful limitation of all forms of communication with outside world.

The control of human communication through environment control.

The cult doesn’t just control communication between people, it also controls people’s communication with themselves, in their own minds.

2. Mystical Manipulation

The inevitable next step after milieu control is extensive personal manipulation. This manipulation assumes a no-holds-barred character, and uses every possible device at the milieu’s command, no matter how bizarre or painful. Initiated from above, it seeks to provoke specific patterns of behavior and emotion in such a way that these will appear to have arisen spontaneously from within the environment. This element of planned spontaneity, directed as it is by an ostensibly omniscient group, must assume, for the manipulated, a near-mystical quality. (Page 422.)

Potential convert is convinced of the higher purpose within the special group.

Everyone is manipulating everyone, under the belief that it advances the “ultimate purpose.”

Experiences are engineered to appear to be spontaneous, when, in fact, they are contrived to have a deliberate effect.

People mistakenly attribute their experiences to spiritual causes when, in fact, they are concocted by human beings.

3. The Demand for Purity

The experiential world is sharply divided into the pure and the impure, into the absolutely good and the absolutely evil. The good and the pure are of course those ideas, feelings, and actions which are consistent with the totalist ideology and policy; anything else is apt to be relegated to the bad and the impure. Nothing human is immune from the flood of stern moral judgements. (Page 423.)

The philosophical assumption underlying this demand is that absolute purity is attainable, and that anything done to anyone in the name of this purity is ultimately moral.

The cult demands Self-sanctification through Purity.

Only by pushing toward perfection, as the group views goodness, will the recruit be able to contribute.

The demand for purity creates a guilty milieu and a shaming milieu by holding up standards of perfection that no human being can attain.

People are punished and learn to punish themselves for not living up to the group’s ideals.

4. The Cult of Confession

Closely related to the demand for absolute purity is an obsession with personal confession. Confession is carried beyond its ordinary religious, legal, and therapeutic expressions to the point of becoming a cult in itself. (Page 425.)

Public confessional periods are used to get members to verbalize and discuss their innermost fears and anxieties as well as past imperfections.

The environment demands that personal boundaries are destroyed and that every thought, feeling, or action that does not conform with the group’s rules be confessed.

Members have little or no privacy, physically or mentally.

5. Aura of Sacred Science

The totalist milieu maintains an aura of sacredness around its basic dogma, holding it out as an ultimate moral vision for the ordering of human existence. This sacredness is evident in the prohibition (whether or not explicit) against the questioning of basic assumptions, and in the reverence which is demanded for the originators of the Word, the present bearers of the Word, and the Word itself. While thus transcending ordinary concerns of logic, however, the milieu at the same time makes an exaggerated claim of airtight logic, of absolute “scientific” precision. Thus the ultimate moral vision becomes an ultimate science; and the man who dares to criticize it, or to harbor even unspoken alternative ideas, becomes not only immoral and irreverent, but also “unscientific”. In this way, the philosopher kings of modern ideological totalism reinforce their authority by claiming to share in the rich and respected heritage of natural science. (Pages 427-428.)

The cult advances the idea that the cult’s laws, rules and regulations are absolute and, therefore, to be followed automatically.

The group’s belief is that their dogma is absolutely scientific and morally true.

No alternative viewpoint is allowed.

No questioning of the dogma is permitted.

6. Loading the Language

The language of the totalist environment is characterized by the thought-terminating cliché. [Slogans] The most far-reaching and complex of human problems are compressed into brief, highly reductive, definitive-sounding phrases, easily memorized and easily expressed.

The cult invents a new vocabulary, giving well-known words special new meanings, making them into trite clichés. The clichés become “ultimate terms”, either “god terms”, representative of ultimate good, or “devil terms”, representative of ultimate evil. Totalist language, then, is repetitiously centered on all-encompassing jargon, prematurely abstract, highly categorical, relentlessly judging, and to anyone but its most devoted advocate, deadly dull: the language of non-thought. (Page 429.)

Controlling words helps to control people’s thoughts.

The group uses black-or-white thinking and thought-terminating clichés.

The special words constrict rather than expand human understanding.

Non-members cannot simply comprehend what cult members are talking about.

7. Doctrine over Person

Another characteristic feature of ideological totalism: the subordination of human experience to the claims of doctrine. (Page 430.)

Past experience and values are invalid if they conflict with the new cult morality.

The value of individuals is insignificant when compared to the value of the group.

Past historical events are retrospectively altered, wholly rewritten, or ignored to make them consistent with doctrinal logic.

No matter what a person experiences, it is belief in the dogma which is important.

Group belief supersedes individual conscience and integrity.

8. Dispensed Existence

The totalist environment draws a sharp line between those whose right to existence can be recognized, and those who possess no such right.

Lifton gave a Communist example:

In thought reform, as in Chinese Communist practice generally, the world is divided into “the people” (defined as “the working class, the peasant class, the petite bourgeoisie, and the national bourgeoisie”), and “the reactionaries” or “the lackies of imperialism” (defined as “the landlord class, the bureaucratic capitalist class, and the KMT reactionaries and their henchmen”). (Page 433.)

The group decides who has a right to exist and who does not.

The group has an elitist world view — a sharp line is drawn by cult between those who have been saved, chosen, etc., (the cult members) and those who are lost, in the dark, etc., (the rest of the world).

Former members are seen as “weak,” “lost,” “evil,” and “the enemy”.

The cult insists that there is no legitimate alternative to membership in the cult.

The full text of Chapter 22 appears HERE courtesy of Dr. Robert Jay Lifton.

7. VIDEO: The Wrong Way Home

An analysis of Dr Arthur J. Deikman’s book on cult behavior

8. Cult Indoctrination through Psychological Manipulation

by Professor Kimiaki Nishida 西田 公昭 of Rissho University in Tokyo.

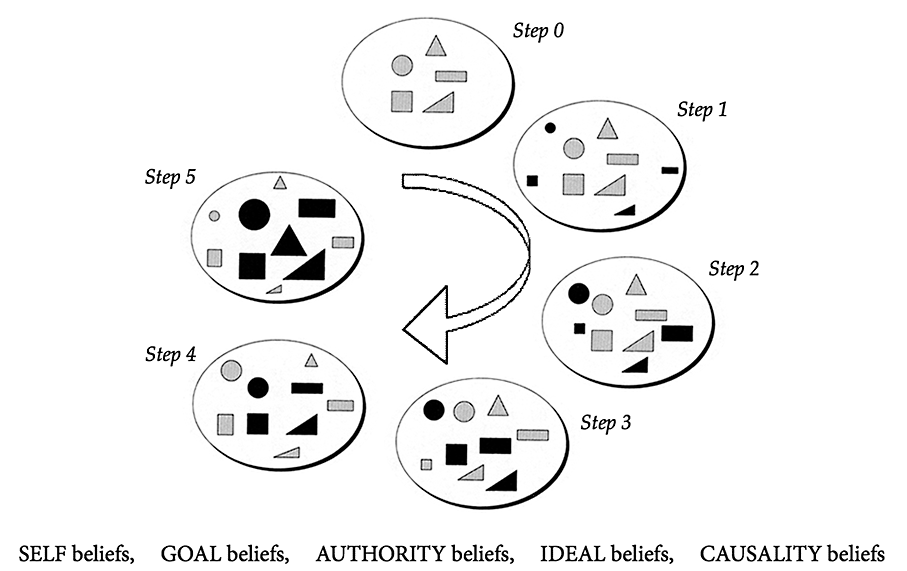

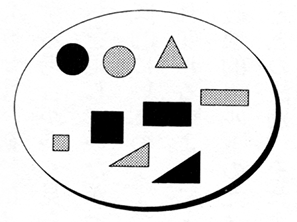

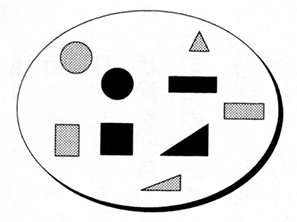

(There is an explanation of this diagram below.)

This is a shortened version of an article entitled Development of the Study of Mind Control in Japan first in published in 2005.

Recently, psychologists in Japan have been examining a contemporary social issue — certain social groups recruit new members by means of psychologically manipulative techniques called “mind control.” They then exhort their members to engage in various antisocial behaviors, from deceptive sales solicitation and forcible donation to suicide and murder [e.g. Tokyo sarin gas attack by Aum Shinrikyō in 1995]. We classify such harmful groups as “cults” or even “destructive cults.” Psychologists concerned with this problem must explain why ordinary, even highly educated people devote their lives to such groups, fully aware that many of their activities deviate from social norms, violate the law, and may injure their health. Psychologists are now also involved in the issue of facilitating the recovery of distressed cult members after they leave such groups.

Background

In the 1970s, hardly anyone in Japan was familiar with the term “destructive cult.” Even if they had been informed of cult activities, such as the 1978 Jonestown tragedy, in which 912 members of the Guyana-based American cult were murdered or committed suicide, most Japanese people would have thought the incident a sensational, curious, and inexplicable event. Because the events at Jonestown occurred overseas, Japanese people, except possibly those worried parents whose child had joined a radical cult, would not have shown any real interest.

In the 1980s, a number of Japanese, including journalists and lawyers, became concerned about the “unethical” activities of the Unification Church, whose members worshiped their so-called True Father, the cult’s Korean founder Sun Myung Moon, who proclaimed himself to be the Second Advent of Christ. One of the group’s activities entailed shady fund-raising campaigns. Another unethical activity of the cult in the 1980s was Reikan-Shôhô, a swindle in which they sold spiritual goods, such as lucky seals, Buddhist rosaries, lucky-towers [pagodas] ornaments, and so on. The goods were unreasonably expensive but the intimidated customers bought them to avoid possible future misfortune [or to liberate their deceased loved-ones from the ‘hell’ they were told they were suffering in].

The first Japanese “anti-cult” organization was established in 1987 to stop the activities of the Unification Church. The organization consisted of lawyers who helped Reikan-Shôhô victims all over Japan (see Yamaguchi 2001). According to their investigation, the lawyers’ organization determined that the Unification Church in Japan engaged in three unethical practices. First, large amounts of money were collected through deceptive means. Under duress, customers desperate to improve their fortunes bankrupted themselves through buying the cult’s “spiritual” goods. Second, members participated in mass marriages arranged by the cult without the partners getting to know each other, after the partners were told by the cult leader that their marriage would save their families and ancestors from calamity. Third, the church practiced mind control, restricting members’ individual freedom, and employing them in forced labor, which often involved illegal activity. Mind-controlled members were convinced their endeavors would liberate their fellow beings.

The 1990s saw studies by a few Japanese psychological researchers who were interested in the cult problem. By the mid-1990s, Japanese courts had already acknowledged two Unification Church liabilities during proceedings the lawyers had brought against the cult; namely, mass marriage and illegal Reikan-shôhô. (see Judgment by the Fukuoka [Japan] District Court on the Unification Church 1995). The lawyers’ main objective, however, had been that the court confirm the Unification Church’s psychological manipulation of cultists, a ruling that would recognize these members as being under the duress of forced labor.

What Is Mind Control?

Early in the study of mind control, the term was equated with the military strategy of brainwashing. Mind control initially was referred to in the United States as “thought reform” or “coercive persuasion” (Lifton 1961; Schein, Schneier, and Barker 1961). Currently, however, mind control is considered to be a more sophisticated method of psychological manipulation that relies on subtler means than physical detention and torture (Hassan 1988).

In fact, people who have succumbed to cult-based mind control consider themselves to have made their decision to join a cult of their own free will. We presume that brainwashing is a behavioral-compliance technique in which individuals subjected to mind control come to accept fundamental changes to their belief system. Cult mind control may be defined as temporary or permanent psychological manipulation by people who recruit and indoctrinate cult members, influencing their behavior and mental processes in compliance with the cult leadership’s desires, and of which control members remain naive (Nishida 1995a).

After the Aum attacks, Ando, Tsuchida, Imai, Shiomura, Murata, Watanabe, Nishida, and Genjida (1998) surveyed almost 9,000 Japanese college students. The questionnaire was designed to determine: whether the students had been approached by cults and, if so, how they had reacted; their perception of alleged cult mind-control techniques; and how their psychological needs determined their reactions when the cults had attempted to recruit them.

Ando’s survey results showed that about 20% of respondent impressions of the recruiter were somewhat favorable, in comparison with their impressions of salespersons. However, their compliance level was rather low. The regression analysis showed that the students tended to comply with the recruiter’s overture when:

• they were interested in what the agent told them;

• they were not in a hurry;

• they had no reason to refuse;

• they liked the agent; or

• they were told that they had been specially selected, could gain knowledge of the truth, and could acquire special new abilities.

When asked to evaluate people who were influenced or “mind controlled” by a cult, respondents tended to think it was “inevitable” those people succumbed, and they put less emphasis on members’ individual social responsibility. When mind control led to a criminal act, however, they tended to attribute responsibility to the individual. More than 70% of respondents answered in the affirmative when asked whether they themselves could resist being subjected to mind control, a result that confirms the students’ naiveté about their own personal vulnerability. The respondents’ needs or values had little effect on their reactions to, interest in, and impressions of cult agents’ attempts to recruit them.

Mind Control as Psychological Manipulation of Cult Membership

Nishida (1994, 1995b) investigated the process of belief-system change caused by mind control as practiced by a religious cult. His empirical study evaluated a questionnaire administered to 272 former group members, content analysis of the dogma in the group’s publications, videotapes of lectures on dogma, the recruiting and seminar manuals, and supplementary interviews with former members of the group.

Cult Indoctrination Process by Means of Psychological Manipulation

In one of his studies, Nishida (1994) found that recruiters offer the targets a new belief system, based on five schemas. These schemas comprise:

1. notions of self concerning one’s life purpose (Self Beliefs);

2. ideals governing the type of individual, society, and world there ought to be (Ideal Beliefs);

3. goals related to correct action on the part of individuals (Goal Beliefs);

4. notions of causality, or which laws of nature operate in the world’s history (Causality Beliefs); and

5. trust that authority will decree the criteria for right and wrong, good and evil (Authority Beliefs) ▲.

Content analysis of the group’s dogma showed that its recruitment process restructures the target’s belief-system, replacing former values with new ones advocated by the group, based on the above schemas.

Abelson (1986) argues that beliefs are metaphorically similar to possessions. He posits that we collect whatever beliefs appeal to us, as if working in a room where we arrange our favorite furniture and objects. He proposes that we transform our beliefs into a new cognitive system of neural connections, which may be regarded as the tools for decision making.

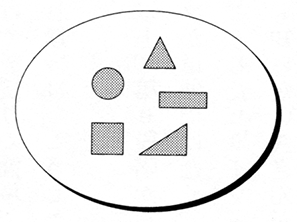

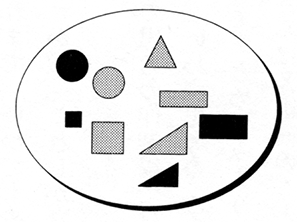

Just as favorite tools are often placed in the central part of a room, or in a harmonious place, it appears that highly valued beliefs are located for easy access in cognitive processing. Meanwhile, much as worn-out tools are often hidden from sight in corners or storerooms, less-valued beliefs are relocated where they cannot be easily accessed for cognitive processing. Individual changes in belief are illustrated with the replacement of a piece of the furniture while a complete belief-system change is represented as exchanging all of one’s furniture and goods, and even the design and color of our room. The belief-system change, such as occurs during the recruitment and indoctrination process, is metaphorically represented in Figure 1 (below), starting with a functional room with its hierarchy of furniture or tools, and progressing through the stages of recruitment and indoctrination to the point at which the functional room has been replaced by a new set of furniture and tools that represent the altered belief system.

Step 0. The Figure shows the five schemas as a set of the thought tools that potential recruits hold prior to their contact with the group.

Step 1. Governed by their trust in authority, targets undergoing indoctrination remain naive about the actual group name, its true purpose, and the dogma that is meant to radically transform the belief system they have held until their contact with the group. At this stage of psychological manipulation, because most Japanese are likely to guard against religious solicitation, the recruiter puts on a good face. The recruiter approaches the targets with an especially warm greeting and assesses their vulnerabilities in order to confound them.

Step 2. While the new ideals and goals are quite appealing to targets, their confidence level in the new notions of causality also rises; some residual beliefs may remain at this stage.

The targets must be indoctrinated in isolation so that they remain unaware that the dogma they are absorbing is a part of cult recruitment. Thus isolated, they cannot sustain their own residual beliefs through observing the other targets; the indoctrination environment tolerates no social reality (Festinger 1954). The goal for this stage is for the targets to learn the dogma by heart and embrace it as their new belief, even if it might seem strange or incomprehensible.

Step 3. At this stage, the recruiter’s repeated lobbying for the new belief system entices the targets to “relocate” those newly absorbed beliefs that appeal to them into the central area in their “rooms.” By evoking the others’ commitment, the recruiter uses group pressure to constrain each target. This approach seems to induce both a collective lack of common sense (Allport 1924) and individual cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957).

Step 4. As the new recruits pass through a period of concentrated study, the earlier conversion of particular values extends to their entire belief system. By the end, they have wholly embraced the new belief system. The attractive new beliefs gradually are “relocated” from their “room’s” periphery into its center, replacing older beliefs. Recently held beliefs are driven to the room’s periphery, thoroughly diminished; new, now-central beliefs coalesce, blending with the few remaining older notions.

Shunning their former society, the targets begin to spend most of their time among group members. Their new social reality raises the targets’ conviction that the new beliefs are proper. At this time, the targets feel contentedly at home because the recruiters are still quite hospitable.

Step 5. The old belief system has become as useless as dilapidated furniture or tools. With its replacement, the transformation of the new recruits’ belief systems results in fully configured new beliefs, with trust in authority at their core, and thus with that authority an effective vehicle for thought manipulation.

At the final stage of psychological manipulation, during the recruitment and indoctrination process, the recruiters invoke the charismatic leader of the group ▲, equating the mortal with god. The recruiters instill a profound fear in the targets, fear that misfortune and calamity will beset them should they leave the cult.

Figure 1. Metamorphosis of the belief system change by cultic psychological manipulation.

Each ellipse represents the working space for decision making. The shapes colored black in the ellipse represent the newly inputted beliefs. The large shapes are developed beliefs, and the shapes in the middle represent beliefs that are highly valued by the individual. ▲ represents the authority of the charismatic leader of the group.

Cult Maintenance and Expansion through Psychological Manipulation

Nishida (1995b) studied one cult’s method of maintaining and expanding its membership by means of psychological manipulation, or cult mind control. The results of factor analysis of his survey data revealed that cult mind-control techniques induced six situational factors that enhanced and maintained members’ belief-systems: (1) restriction of freedom, (2) repression of sexual passion, (3) physical exhaustion, (4) punishment for external association, (5) reward and punishment, and (6) time pressure.

Studies also concluded that four types of complex psychological factors influence, enhance, and maintain members’ belief systems: (1) behavior manipulation, (2) information-processing manipulation, (3) group-processing manipulation, and (4) physiological-stress manipulation.

Behavior Manipulation

Behavior manipulation includes the following factors:

1 Conditioning. The target members were conditioned to experience deep anxiety if they behaved against cult doctrine. During conditioning, they would often be given small rewards when they accomplished a given task, but strong physical and mental punishment would be administered whenever they failed at a task.

2 Self-perception. A member’s attitude to the group would become fixed when the member was given a role to play in the group (Bem 1972; Zimbardo 1975).

3 Cognitive dissonance. Conditions are quite rigorous because members have to work strenuously and are allowed neither personal time nor money, nor to associate with “outsiders.” It seems that they often experienced strong cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957).

Information-Processing Manipulation

Information-processing manipulation factors include the following:

1 Gain-loss effect. Swings between positive and negative attitudes toward the cult became fixed as more positive than negative (Aronson and Linder 1965). Many members had negative attitudes toward cults prior to contact with their group.

2 Systemization of belief-system. In general, belief has a tenacious effect, even when experience shows it to be erroneous (Ross, Lepper, and Hubbard 1975). Members always associate each experience with group dogma; they are indoctrinated to interpret every life event in terms of the cult’s belief-system.

3 Priming effect. It is a cognitive phenomenon that many rehearsed messages guide information processing to take a specific direction (Srull and Wyer 1980). The members listen to the same lectures and music frequently and repeatedly, and they pray or chant many times every day.

4 Threatening messages. They are inculcated with strong fears of personal calamity by means of [illnesses such as cancer, accidents, influence of evil spirits, “restored after satan”], and so on.

Group-Processing Manipulation

Group-processing manipulation components include:

1 Selective exposure to information. Members avoid negative reports, but search for positive feedback once they make a commitment to the group (Festinger 1957). It should also be added that many group members continue to live in the locale in which they exited their society. Even so, new members are forbidden to have contact with out-of-group people, or access to external media.

2 Social identity. Members identify themselves with the group because the main goal or purpose of their activity is to gain personal prestige within the group (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, and Wetherell 1987). Therefore, they look upon fellow members as elite, acting for the salvation of all people. Conversely, they look on external critics as either wicked persecutors or pitiful, ignorant fools. This “groupthink” makes it possible for the manipulators to provoke reckless group behavior among the members (Janis 1971; Wexler 1995).

Physiological-Stress Manipulation

It has been established that physiological stress factors facilitate this constraint within the group based on the following, as examples:

1 urgent individual need to achieve group goals,

2 fear of sanction and punishment,

3 monotonous group life,

4 sublimation of sexual drive in fatiguing hard work,

5 sleep deprivation,

6 poor nutrition,

7 extended prayer and / or [study sessions].

Post-Cult Residual Psychological Distress

Over the past few decades, a considerable number of studies have been completed on the psychological problems former cult members have experienced after leaving the cult, as compared with the mind-control process itself.

It is important to note that most former members continue to experience discontent, although its cause remains controversial (Aronoff, Lynn, and Malinoski 2000). A few studies on cult phenomena have been conducted so far in Japan, notably by Nishida (1995a, 1998), and by Nishida and Kuroda (2003, 2004), who investigated ex-cultists’ post-exit problems, based mainly on questionnaires administered to former members of two different cults.

In a series of studies, Nishida and Kuroda (2003) surveyed 157 former members of the Unification Church and Aum Shinrikyō. Using factor analysis, the studies posited eleven factors that contribute to ex-members’ psychological problems. These factors can be classified into three main groups: (1) emotional distress, (2) mental distress, and (3) interpersonal distress. The eleven factors are (1) tendencies to depression and anxiety, (2) loss of self-esteem, (3) remorse and regret, (4) difficulty in maintaining social relations and friendships, (5) difficulty in family relationships, (6) floating or flashback to cultic thinking and feeling, (7) fear of sexual contact, (8) emotional instability, (9) hypochondria, (10) secrecy of cult life, and (11) anger toward the cult. These findings seem to have a high correlation with previous American studies.

Moreover, Nishida and Kuroda (2004) deduced from their analysis of variance of the 157 former members surveyed that depression and anxiety, hypochondria, and secrecy of cult involvement decreased progressively, with the help of counseling, after members left the cult. However, loss of self-esteem and anger toward the cult increased as a result of counseling.

Furthermore, Nishida (1998) found clear gender differences in the post-exit recovery process. Although female ex-cultists’ distress levels were higher than those of the males immediately after they left the cults, the women experienced full recovery more quickly than the men. The study also found that counseling by non-professionals works effectively with certain types of distress, such as anxiety and helplessness, but not for others, such as regret and self-reproof.

Conclusion

It can be concluded from Japanese studies on destructive cults that the psychological manipulation known as cult mind control is different from brainwashing or coercive persuasion. Based on my empirical studies, conducted from a social psychology point of view, I concluded that many sets of social influence are systematically applied to new recruits during the indoctrination process, influences that facilitate ongoing control of cult members. My findings agree with certain American studies, such as those conducted by Zimbardo and Anderson (1993), Singer and Lalich (1995), and Hassan (1988, 2000). The manipulation is powerful enough to make a vulnerable recruit believe that the only proper action is to obey the organization’s leaders, in order to secure humanity’s salvation, even though the requisite deed may breach social norms. Furthermore, it should be pointed out that dedicated cult veterans are subject to profound distress over the extended period of their cult involvement.

This chapter is a reprint of an article originally published in Cultic Studies Review, 2005, Volume 4, Number 3, pages 215-232.

Kimiaki Nishida, Ph.D., a social psychologist in Japan, is Associate Professor at the Rissho University 立正大学 in Tokyo and a Director of the Japan Cult Recovery Council. He is a leading Japanese cultic studies scholar and the editor of Japanese Journal of Social Psychology. His studies on psychological manipulation by cults were awarded prizes by several academic societies in Japan. And he has been summoned to some courts to explain “cult mind control.”

9. Towards a Demystified and Disinterested Scientific Theory of Brainwashing

by Benjamin Zablocki

from Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field

Edited by Benjamin Zablocki and Thomas Robbins

[This item has been expanded and moved HERE ]

Nobody likes to lose a customer, but religions get more touchy than most when faced with the risk of losing devotees they have come to define as their own. Historically, many religions have gone to great lengths to prevent apostasy, believing virtually any means justified to prevent wavering parishioners from defecting and thus losing hope of eternal salvation. …

10. Psyching Out the Cults’ Collective Mania

by Louis Jolyon West and Richard Delgado

Los Angeles Times November 26, 1978

Louis Jolyon West is director of UCLA’s Neuropsychiatric Institute. Richard Delgado is a visiting professor of law at UCLA.

Just a week ago yesterday, the ambush of Rep. Leo J. Ryan and three newsmen at a jungle airstrip set off a terrible sequence of events that left many hundreds of people dead in the steamy rain forests of Guyana. The horrible social mechanism that ground into motion in the Peoples Temple camp that day seems inexplicable to many and has focused attention on the murky world of cults, both religious and nonreligious.

Historically, periods of unusual turbulence are often accompanied by the emergence of cults. Following the fall of Rome, the French Revolution and again during the Industrial Revolution, numerous cults appeared in Europe. The westward movement in America swept a myriad of religious cults toward California. In the years following the Gold Rush, at least 50 utopian cults were established here. Most were religious and lasted, on the average, about 20 years; the secular variety usually endured only half that long.

The present disturbances in American culture first welled up during the 1960s, with the expansion of an unpopular war in Southeast Asia, massive upheavals over civil rights and a profound crisis in values in response to unprecedented affluence, on the one hand, and potential thermonuclear holocaust, on the other. Our youth were caught up in three rebellions: red (the New Left), against political and economic monopolies; black, against racial injustice, and green (the counterculture), against materialism in all its manifestations, including individual and institutional struggles for power.

Drug abuse and violent predators took an awful toll among the counterculture’s hippies in the late 1960s. Many fled to form colonies, now generally called communes. Others turned to the apparent security of paternalistic religious and secular cults, which have been multiplying at an astonishing rate ever since.

Those communes that have endured—perhaps two or three thousand in North America—can generally be differentiated from cults in three respects:

— Cults are established by strong charismatic leaders of power hierarchies controlling resources, while communes tend to minimize organizational structure and to deflate or expel power seekers.

— Cults possess some revealed “word” in the form of a book, manifesto or doctrine, whereas communes vaguely invoke general commitments to peace, libertarian freedoms and distaste for the parent culture’s establishments.

— Cults create fortified boundaries confining their members in various ways and attacking those who would leave as defectors, deserters or traitor; they recruit new members with ruthless energy and raise enormous sums of money, and they lend to view the outside world with increasing hostility and distrust as the organization ossifies. In contrast, communes are like nodes in the far-flung network of the counterculture. Their boundaries are permeable membranes through which people come and go relatively unimpeded, either to continue their pilgrimages or to return to a society regarded by the communards with feelings ranging from indifference to amusement to pity. Most communes thus defined seem to pose relatively little threat to society. Many cults, on the other hand, are increasingly perceived as dangerous both to their own members and to others.

Recent estimates place more than 2 million Americans, mostly aged 18 to 25, in some way affiliated with cults and, by using the broadest of definitions, there may be as many as 2,500 cults in America today. If the total seems large, consider that L. Ron Hubbard’s rapidly expanding Church of Scientology claimed 5.5 million members worldwide in 1972; the Unification Church of Rev. Sun Myung Moon boasts of 30,000 members in the United States alone.

These enterprises may seem rich, respectable and secure compared to the Reverend Jim Jones tragic Peoples Temple, with its membership of only 2,000 to 3,000. However, the Church of Scientology, the Unification Church and other organizations such as Chuck Dederich’s Synanon, have all been under recent investigation by government agencies. Other large religious cults, such as the Divine Light Mission, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness and the Children of God are being carefully scrutinized by the public. For the public is alarmed by what it knows of some cults’ methods of recruitment, exploitation of members, restriction on members freedom, retaliation against defecting members, struggles with members’ families engaged in rescue operations (including so-called “deprogramming”), dubious fiscal practices and the like. Lately, death threats against investigative reporters, leaked internal memoranda justifying violence, the discovery of weapons caches, such incidents as the rattlesnake attack against the Los Angeles attorney Paul Morantz last month, the violent outburst of the Hanafi Muslims in Washington, D.C., last year and now the gruesome events in Guyana have served to increase the public’s concern.

[The 1977 Hanafi Siege occurred on March 9-11, 1977 when three buildings in Washington, D.C. were seized by 12 Hanafi Muslim gunmen. The gunmen were led by Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, who wanted to bring attention to the murder of his family in 1973. They took 149 hostages and killed radio journalist Maurice Williams. Police officer Mack Cantrell also died.]

Some cults (for instance, Synanon) are relatively passive about recruitment (albeit harsh when it comes to defections). Others, such as the Unification Church, are tireless recruiters. Many employ techniques that in some respects resemble those used in the forceful political indoctrination prescribed by Mao Tse-tung during the communist revolution and its aftermath in China. These techniques, described by the Chinese as “thought reform” or “ideological remolding,” were labeled “brainwashing” in 1950 by the American journalist Edward Hunter. Such methods were subsequently studied in depth by a number of western scientists and Edgar Schein summarized much of this research in a monograph, “Coercive Persuasion,” published in 1961.

Successful indoctrination by a cult of a recruit is likely to require most of the following elements:

— Isolation of the recruit and manipulation of his environment;

— Control over channels of communication and information;

— Debilitation through inadequate diet and fatigue;

— Degradation or diminution of the self;

— Early stimulation of uncertainty, fear and confusion, and joy and certainty as rewards for surrendering self to the group;

— Alternation of harshness and leniency in the context of discipline;

— Peer pressure, often applied through ritualized “struggle sessions,” generating guilt and requiring open confessions;

— Insistence by seemingly all-powerful hosts that the recruit’s survival –physical or spiritual– depends on identifying with the group;

— Assignment of monotonous tasks of repetitive activities, such as chanting or copying written materials;

— Acts of symbolic betrayal or renunciation of self, family and previously held values, designed to increase the psychological distance between the recruit and his previous way of life.

As time passes, the new member’s psychological condition may deteriorate. He may become incapable of complex, rational thought; his responses to questions may become stereotyped and he may find it difficult to make even simple decisions unaided. His judgement about the events in the outside world will likely be impaired. At the same time, there may be such a reduction of insight that he fails to realize how much he has changed.

After months or years of membership, such a former recruit may emerge from the cult –perhaps “rescued” by friends or family, but more likely having escaped following prolonged exploitation, suffering and disillusionment. Many such refugees appeared dazed and confused, unable to resume their previous way of life and fearful of being captured, punished and returned to the cult. “Floating” is a frequent phenomenon, with the ex-cultist drifting off into disassociated states of altered consciousness. Other frequent symptoms of the refugees include depression, indecisiveness and a general sense of disorientation, often accompanied by frightening impulses to return to the cult and throw themselves on the mercy of the leader.

This suggests that society may well wish to consider ways of preventing its members, particularly the young, from unwittingly becoming lost in cults that use psychologically and even physically harmful techniques of persuasion. Parents can inform themselves and their children about cults and the dangers they pose; religious and educational leaders can teach the risks of associating with such groups. However, when prevention fails and intervention assumes an official character –as through legislation or court action– it is necessary to consider the potential impact of such intervention on the free exercise of religion as guaranteed by the First Amendment.

Under the U.S. Constitution, religious liberty is of two types –freedom of belief and freedom of action. The first is, by its nature, absolute. An individual may choose to believe in a system that others find bizarre or ludicrous; society is powerless to interfere. Religiously motivated conduct, however, is not protected absolutely. Instead, it is subject to a balancing test, in which courts weigh the interest of society in regulating or forbidding the conduct against the interest of the group in carrying it out.

How can society best protect the individual from physical and psychological harm, from stultification of his ability to act autonomously, from loss of vital years of his life, from dehumanizing exploitation –all without interfering with his freedom of choice in regard to religious practices? And, while protecting religious freedom, how can society protect the family as a social institution from the menace of the cult as a competing super-family?

A number of legal cases involving polygamy, blood transfusions for those who object to them on religious grounds and the state’s interest in protecting children from religious zealotry suggest that the courts will hold these interests to be constitutionally adequate to check the more obvious abuses of the cults. Furthermore, the cults interest is likely to be found weakened by a lack of “sincerity,” a requirement deriving from conscious-objector and tax-exemption cases, and lack of “centrality,” or importance of the objectionable practices to such essential religious functions as worship.

To be protected by the First Amendment, religions conduct must stem from theological or moral motives rather than avarice, personal convenience, or a desire for power. Such conduct must also constitute a central or indispensable element of the religious practice.

Many religious cults demonstrate an extreme interest in financial or political aggrandizement, but little interest in the spiritual development of the faithful. Because their religious or theological core would not seem affected by a prohibition against deceptive recruiting methods and coercive techniques to indoctrinate and retain members, it is likely the courts would consider the use of such methods neither “sincere” nor “central.”

Thus the constitutional balance appears to allow intervention, though it could be objected that obnoxious practices which might otherwise justify intervention should not be considered harmful if those experiencing them do so voluntarily and do not see them as harmful at the time.

But is coercive persuasion in the cults inflicted on persons who freely choose to undergo it —who decide to be unfree— or is it imposed on persons who do not truly choose it of their own free will? The decision to join a cult and undergo drastic reformation of one’s thought and behavioral processes can be seen as similar in importance to decisions to undergo surgery, psychotherapy and other forms of medical treatment. Accordingly, it should be protected in the same manner and to the same degree as we protect the decision to undergo medical treatment. This means the decision must be fully consensual. This entails, at a minimum, that those making such decisions do so with both full mental “capacity” and with a complete “knowledge” of the choices offered them. In other words, they should give “fully informed consent” before the process of indoctrination can be initiated.

A review of legislative reports, court proceedings (including cases involving conservatorships, or the “defense of necessity” in kidnaping prosecutions), and considerable clinical material makes clear that the cult joining process is often not fully consensual. It is not fully consensual because “knowledge” and “capacity” —the essential elements of legally adequate consent— are not simultaneously present. Until cults obtain fully informed consent from prospective members giving permission in advance to apply the procedures of indoctrination, and warning of the potential risks and losses, it appears that society may properly take measures to protect itself against cultist indoctrination without violating the principle, central to American jurisprudence, that the state should not interfere with the voluntarily chosen religious behavior of adult citizens.

Most young people who are approached by cultist recruiters will have relatively unimpaired “capacity”. They may be undergoing a momentary state of fatigue, depression, or boredom; they may be worried about exams, a separation from home or family, the job market, or relations with the opposite sex —but generally their minds are intact. If the recruiter were to approach such a person and introduce himself or herself as a recruiter for a cult, such as the Unification Church, the target person would likely be on guard.

But recruiters usually conceal the identity of the cult at first, and the role the recruit is expected to play in it, until the young person has become fatigued and suggestible. Information is imparted only when the target’s capacity to analyze it has become low. In other words, when the recruit’s legal “capacity” is high, his “knowledge” is not; later the reverse obtains. Consent given under such circumstances should not deserve the respect afforded ordinary decisions of competent adults.

If intervention against cults that employ coercive persuasion is consistent with the First Amendment, a line must be drawn between cults and other organizations. But is it possible to impose restrictions on the activities of cults that use coercive persuasion without imposing the same restraints upon other societal institutions —TV advertising, political campaigns, army training camps, Jesuit seminaries— that use influence, persuasion and group dynamics in their normal procedures?

Established religious orders may sequester their trainees to some extent. Military recruiters and Madison Avenue copywriters use exaggeration, concealment and “puffing” to make their product appear more attractive than it is. Revivalists invoke guilt. Religious mystics engage in ritual fasting and self-mortification. It has been argued that the thought-control processes used by cults are indistinguishable from those of more socially accepted groups.

Yet it is possible to distinguish between cults and other institutions —by examining the intensity and pervasiveness with which mind-influencing techniques are applied. For instance, Jesuit seminaries may isolate the seminarian from the rest of the world for periods of time, but the candidate is not deliberately deceived about the obligations and burdens of the priesthood; in fact, he is warned in advance and is given every opportunity to withdraw.

In fact, few, if any, social institutions claiming First Amendment protection use conditioning techniques as intense, deceptive, or pervasive as those employed by many contemporary cults. A decision to intervene and prevent abuses of cult proselytizing and indoctrinating does not by its logic alone dictate intervention in other areas where the abuses are milder and more easily controlled.

To turn again to the sad case of the Peoples Temple, it seemed to be, for some years, a relatively small and, in its public stance, moderate cult. Its members differed from those of most cults: Many were older people, many were black, many were enlisted in family units. Nevertheless, from its origins, based on professed ideals of racial harmony and economic equality, the cult gradually developed typical cultist patterns of coercive measures, harsh practices, suspicions of the outside world and a siege mentality.

It may be that these developments comprise an institutional disease of cults. If so, the recent events in Guyana pose a new warning of continuing dangers from cults. For as time passes, leaders may age and sicken. The cult’s characteristically rigid structure and its habitual deference to the leader as repository of all authority leaves the membership vulnerable to the consequences of incredible errors of judgment, institutional paranoia and even deranged behavior by the cult’s chief.

Perhaps the tragedy of Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple will lead to more comprehensive and scientific studies of cult phenomena. Perhaps it will lead our society to a more reasoned public policy of prevention and intervention against further abuses by cults in the name of freedom of religion. If so, then perhaps the disaster in Guyana will have some meaning after all.

11. Take Back Your Life by Janja Lalich and Madeleine Tobias

Paperback: 374 pages

Publisher: Bay Tree Publishing; 2nd edition (September 10, 2009)

Cult victims and those who have experienced abusive relationships often suffer from fear, confusion, low self-esteem, and post-traumatic stress. Take Back Your Life explains the seductive draw that leads people into such situations, provides insightful information for assessing what happened, and hands-on tools for getting back on track. Written for victims, their families, and professionals, this book leads readers through the healing process.

About the Authors

Janja Lalich, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of Sociology at California State University, Chico. She has been studying the cult phenomenon since the late 1980s and has coordinated local support groups for ex-cult members and for women who were sexually abused in a cult or abusive relationship. She is the author of Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults, and co-author, with Margaret Singer, of Cults in Our Midst.

Madeleine Tobias, M.S., R.N., C.S., is the Clinical Coordinator and a psychotherapist at the Vet Center in White River Junction, Vermont, where she treats veterans who experienced combat and/or sexual trauma while in the military. Previously she had a private practice in Connecticut and was an exit counselor helping ex-members of cultic groups and relationships.

“If you buy one book on cults, this could be top of the list.”

Here are three reviews of an earlier edition:

An essential roadmap to recovery

For me, the special usefulness of this book came in the form of material directed at children who grew up in a cult, who have no other frame of reference to go back to.

The information I gleaned here gave me that frame of reference, and helped me to “detox” from the environment which was so seductively calling me back. It explains and makes sense of some very bewildering and deceptive manipulation techniques. And it has helped my therapy by outlining the kinds of issues that children coming out of cults usually face.

This book has a universal appeal for all cult escapees because it focuses not on beliefs or practices, but rather on manipulations and psychological pressures which are commonly brought to bear in cults. I found it easy to identify experientially with the material, without being challenged and put off by attacks on my strange belief system which I was still disengaging from.

It’s been a big part of my recovery. My thanks to the authors!

____________

A must-read for former cult members by Troy Waller:

I wish I had found this book immediately after leaving the cult I was involved in.

This book offers invaluable assistance to those who have been involved with a destructive cult, whether it be religious, political or psycho-therapeutic. The text gives former members indications of what to expect in recovery as well as practical assistance to cope with their recovery.

The text also gives a breakdown of how and why cults operate as they do; how and why people get recruited into cults; and how and why people leave cults.

This book is truly a gift from the authors’ heart, experiences and study. Thanks to them.

____________

Sane Advice for Those Leaving Cults by D. L. Barnett

We don’t hear much these days about the Branch Davidians, Heaven’s Gate or even Jim Jones. It’s tempting to think that the cult movement has faded and that the world’s attention is on more pressing matters – like suicide bombers. But they are all of a piece, according to Chico State University Associate Professor of Sociology Janja Lalich.

In “Take Back Your Life: Recovering from Cults and Abusive Relationships,” Lalich and co-author Madeleine Tobias, a Vermont psychotherapist, make clear that modern day cults have not disappeared. “If there is less street recruiting today, it is because many cults now use professional associations, campus organizations, self-help seminars, and the Internet as recruitment tools” to entice the unwary.

Who gets sucked into a cult? “Although the public tends to think, wrongly, that only those who are stupid, weird, crazy and aimless get involved in cults, this is simply untrue. … We know that many cult members went to the best schools in the country, have advanced academic or professional degrees and had successful careers and lives prior to their involvement in a cult or cultic abusive relationship. But at a vulnerable moment, and we all have plenty of those in our lives (a lost love, a lost job, rejection, a death in the family and so on), a person can fall under the influence of someone who appears to offer answers or a sense of direction.”

For the authors, “a group or relationship earns the label ‘cult’ on the basis of its methods and behaviors – not on the basis of its beliefs. Often those of us who criticize cults are accused of wanting to deny people their freedoms, religious or otherwise. But what we critique and oppose is precisely the repression and stripping away of individual freedoms that tends to occur in cults. It is not beliefs that we oppose, but the exploitative manipulation of people’s faith, commitment, and trust.”

Written for those coming out of cults, as well as for family members and professionals, “Take Back Your Life” deals with common characteristics of myriad cult types: Eastern, religious and New Age cults; political, racist and terrorist cults; psychotherapy, human potential, mass transformational cults; commercial, multi-marking cults; occult, satanic or black-magic cults; one-on-one family cults; and cults of personality. …

The book features riveting personal accounts from ex-cult members and offers a wide range of resources for the person who is trying to retrieve his or her “pre-cult” personality. Education looms large, for that can begin to break down the narrow black-and-white thinking cult members often display. Many cults redefine common terms or introduce special vocabulary making it difficult for members to make sense of the world outside of even their own inner aspirations.

The authors are also concerned about those in the education and helping professions who don’t see the dangers posed by cults both to the individual and the larger community. Part of the purpose of the book is to make a credible case that any course of therapy needs to take into account a patient’s cult associations.

“Take Back Your Life” is a book of hope, an excellent starting point for those thinking of exiting a cult and for those who are taking back their lives, one day at a time.

Contents

Acknowledgments ix

Introduction 1

Part One – The Cult Experience 7

1. Defining a Cult 9

2. Recruitment 18

3. Indoctrination and Resocialization 36

4. The Cult Leader 52

5. Abusive Relationships and Family Cults 72

Part Two – The Healing Process 87

6. Leaving a Cult 89

7. Taking Back Your Mind 104

8. Dealing with the Aftereffects 116

9. Coping with Emotions 127

10. Building a Life 151

11. Facing the Challenges of the Future 166

12. Healing from Sexual Abuse and Violence 180

13. Making Progress by Taking Action 196

14. Success Is Sweet: Personal Accounts 212

Part Three – Families and Children in Cults 239

15. Born and Raised in a Cult 241

16. Our Lives to Live: Personal Accounts 259

17. Child Abuse in Cults 280

Nori J. Muster

Part Four – Therapeutic Concerns 287

18. Therapeutic Issues 289

19. The Therapist’s Role 305

Shelly Rosen

20. Former Cult Members and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder 314

Appendixes

A. Characteristics Associated with Cultic Groups 327

Janja Lalich and Michael Langone

B. On Being Savvy Spiritual Consumers 329

Rosanne Henry and Sharon Colvin

C. Resources 332

D. Recommended Reading 336

Notes 345

Author Index 359

Subject Index 363

Introduction

Take Back Your Life: Recovering from Cults and Abusive Relationships gives former cult members, their families, and professionals an understanding of common cult practices and their aftereffects. This book also provides an array of specific aids that may help restore a sense of normalcy to former cult members’ lives.

About twelve years ago, we wrote our first book on this topic: Captive Hearts, Captive Minds: Freedom and Recovery from Cults and Abusive Relationships. Over the years, we received mounds of positive feedback about that book in the form of letters, phone calls, postcards, emails, faxes, and personal contact at conferences and in our professional lives. Former cult members, families, therapists, and exit counselors continually told us that Captive Hearts, Captive Minds was always their number-one book. That positive reception (and the need to provide up-to-date information) was the impetus for this new book. We are delighted to offer this new resource to people who want to evaluate, understand, and, in many cases, recover from the effects of a cult experience. We hope this book will help you take back your life.

Cults did not fade away (as some would like to believe) with the passing of the sixties and the disappearance of the flower children. In fact, cult groups and relationships are alive and thriving, though many groups have matured and “cleaned up their act.” If there is less street recruiting today, it is because many cults now use professional associations, campus organizations, self-help seminars, and the Internet as recruitment tools. Today we see people of all ages— even multigenerational families—being drawn into a wide variety of groups and movements focused on everything from therapy to business ventures, from New Age philosophies to Bible-based beliefs, and from martial arts to political change.

Most cults don’t stand up to be counted in a formal sense. Currently, the best estimates tell us that there are about 5,000 such groups in the United States, some large, some remarkably small. Noted cult expert and clinical psychologist Margaret Singer estimated “about 10 to 20 million people have at some point in recent years been in one or more of such groups.”(1) Before its enforced demise, the national Cult Awareness Network reported receiving about 20,000 inquiries a year.(2)

A cult experience is often a conflicted one, as those of you who are former members know. More often than not, leaving a cult environment requires an adjustment period so that you can put yourself and your life back together in a way that makes sense to you. When you first leave a cult situation, you may not recognize yourself. You may feel confused and lost; you may feel both sad and exhilarated. You may not know how to identify or tackle the problems you are facing. You may not have the slightest idea about who you want to be or what you want to believe. The question we often ask children, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” takes on new meaning for adult ex-cult members.

Understanding what happened to you and getting your life back on track is a process that may or may not include professional therapy or pastoral counseling. The healing or recovery process varies for each of us, with ebbs and flows of progress, great insight, and profound confusion. Also, certain individual factors will affect your recovery process. One is the length and intensity of your cult experience. Another is the nature of the group or person you were involved with—or where your experience falls on a scale of benign to mildly harmful to extremely damaging. Recovering from a cult experience will not end the moment you leave the situation (whether you left on your own or with the help of others). Nor will it end after the first few weeks or months away from your group. On the contrary, depending on your circumstances, aspects of your cult involvement may require some attention for the rest of your life.

Given that, it is important to find a comfortable pace for your healing process. In the beginning, particularly, your mind and body may simply need a rest. Now that you are no longer on a mission to save the world or your soul, relaxation and rest are no longer sinful. In fact, they are absolutely necessary for a healthy, balanced, and productive life.

Reentering the non-cult world (or entering it for the first time if you were born or raised in a cult) can be painful and confusing. To some extent, time will help. Yet the passage of time and being physically out of the group are not enough. You must actively and of your own initiative face the issues of your involvement. Let time be your ally, but don’t expect time alone to heal you. We both know former cult members who have been out of their groups for many years but who have never had any counseling or education about cults or the power of social-psychological influence and control. These individuals live in considerable emotional pain and have significant difficulties due to unresolved conflicts about their group, their leader, or their own participation. Some are still under the subtle (or not so subtle) effects of the group’s systems of influence and control.

A cult experience is different for each person, even for members of the same group, family, or situation. Some former members may have primarily positive impressions and memories, while others may feel hurt, used, or angry. The actual experiences and the degree or type of harm suffered may vary considerably. Some people may leave cults with minimum distress, and adjust rather rapidly to the larger society, while others may suffer severe emotional trauma that requires psychiatric care. Still others may need medical attention or other care. The dilemmas can be overwhelming and may require thoughtful attention. Many have likened this period to being on an emotional roller coaster.

First of all, self-blame (for joining the cult or participating in it, or both) is a common reaction that tends to overshadow all positive feelings. Added to this is a feeling of identity loss and confusion over various aspects of daily life. If you were recruited at any time after your teens, you already had a distinct personality, which we call the “pre-cult personality.” While you were in the cult, you most likely developed a so-called new personality in order to adapt to the demands and ambiance of cult life. We call this the “cult personality.” Most cults engage in an array of social-psychological pressures aimed at indoctrinating and changing you. You may have been led to believe that your pre-cult personality was all bad and your adaptive cult personality all good. After you leave a cult, you don’t automatically switch back to your pre-cult self; in fact, you may often feel as if you have two personalities or two selves. Evaluating these emotions and confronting this dilemma—integrating the good and discarding the bad—is a primary task for most former cult members, and is a core focus of this book.

As you seek to redefine and reshape your identity, you will want to address the psychological, emotional, and physical consequences of living in or around a constrained, controlled, and possibly abusive environment. And as if all that weren’t enough, many basic life necessities and challenges will need to be met and overcome. These may include finding employment and a place to live, making friends, repairing old relationships, confronting belief issues, deciding on a career or going back to school, and most likely catching up with a social and cultural gap.

If you feel like “a stranger in a strange land,” it may be consoling to know that you are not the first person to have felt this way. In fact, the pervasive and awkward sense of alienation that both of us felt when we left our cults motivated us to write this book. We hope that the information here will not only help you get rid of any shame or embarrassment you might feel, but also ease your integration into a positive and productive life.