In The Shadow Of The Moons: My Life In The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Family.

In The Shadow Of The Moons: My Life In The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Family.

by Nansook Hong

Little, Brown & Co. Boston, New York, Toronto & London, 1998

ISBN 0-316-34816-3

The book has also been published in Japanese, French and German. A Spanish translation is now available. (see below)

The ‘ghost writer’ who helped with Nansook Hong’s book was Eileen McNamara from the Boston Globe (Globe Metro columnist). Nansook needed help with her English. The story is authentically that of Nansook Hong.

Sun Myung Moon selected Nansook to be the wife of his dissolute son, Hyo Jin Moon. In 1982 the age of consent was 17 in New York state. Nansook was married at 15, pregnant at 16, and a mother at 17.

Back cover text

THE EIGHTEEN-ACRE SECLUDED COMPOUND where we lived in Irvington, forty minutes north of New York City, is the world headquarters of the Unification Church and the home of the founder of the religious movement the world knows as “Moonies.” The estate, called East Garden, had been my personal prison for fourteen years, since the day the Reverend Moon summoned me from Korea to be the child bride of his eldest son, the heir to Moon’s divine mission and earthly empire. Then, I was only fifteen, a naive schoolgirl eager to serve her God. Now, I was a woman ready to reclaim her life. Today, I would escape. I would take the only thing holy about this marriage, my children, and leave behind the man who beat me and the false Messiah who let him, men so flawed that I now knew that God would never have chosen Sun Myung Moon or his son to be his agents on earth.

Accepting the Reverend Moon for the fraud I now know him to be was a slow and painful process. It was only possible because that realization, in the end, did not shake my faith in God. Moon had failed God, but God had not failed me. It was God alone who comforted me, a woman-child in the hands of a husband who treated me either as a toy for his sexual pleasure or as an outlet for his violent rages.

God was guiding me now as I surveyed my sleeping children and the suitcases we had been packing clandestinely for weeks. My belief in the Reverend Sun Myung Moon had been at the center of my life for twenty-nine years, but a shattered faith is no match for a mother’s love. My children had been my sole source of joy in the cloistered, poisonous world of the True Family. I had to flee for their sake, as well as my own.

▲ I am singing at a Moon family birthday celebration at the mansion in East Garden. The Reverend Sun Myung Moon would make each of us sing at family and church gatherings, a practice I dreaded because of the poor quality of my voice.

▲ I am singing at a Moon family birthday celebration at the mansion in East Garden. The Reverend Sun Myung Moon would make each of us sing at family and church gatherings, a practice I dreaded because of the poor quality of my voice.

Book cover flaps

“I HAVE NEVER KNOWN exactly why Sun Myung Moon chose me to marry his eldest son. As the years went on, I came to believe that my youth and naïveté were the central reasons for my selection. His ideal wife was a girl young and passive enough to submit while he molded her into the woman he wanted. Time would prove that I was young, but not nearly passive enough.”

Born in South Korea to deeply religious parents, Nansook Hong attended Sunday school; was taught not to smoke, drink, or have premarital sex; and believed in a Messiah who would one day save mankind. That Messiah was the Reverend Sun Myung Moon, leader of the Unification Church.

Daughter of prominent church members, Nansook was handpicked at age fifteen by the Reverend Moon to marry his son, Hyo Jin, the heir to Moon’s spiritual and economic empire. Abruptly uprooted from her life in Korea, Nansook moved to the Moon family’s opulent, secluded compound not far from New York City and began her sophomore year in high school, speaking no English and concealing a marriage that could have brought charges of statutory rape. Her misery quickly became complete—her husband slept with prostitutes and drank, while his parents blamed Nansook for failing to reform their wayward son. Worse still was the hypocrisy she witnessed in the lives of the Moon family, who claimed to be sinless embodiments of family values. Instead, she was confronted with greed, adultery, illicit drugs, and eventually physical violence.

During her fourteen-year marriage to Hyo Jin Moon, Nansook bore five children while attending high school and Barnard College in Manhattan. Her children provided her only comfort in a life of loneliness and fear. Finally, with the support of a few allies and an unbending faith in God, she made a risky escape from the compound. This is the harrowing tale of her years as an abused wife and privileged member of a religious cult, and her fight to create a life for herself and her children, beyond the shadow of the Moons.

For my children

Table of Contents

Prologue

pages 3-12

The bleating of my beeper snapped me awake. I realized in a panic that the sun was already up. Light, streaming through the bay windows, played on the blue striped wallpaper of my baby’s nursery. I could see the outline of the hills outside from the floor at the foot of Shin Hoon’s crib, where I must have fallen asleep just before August 8, 1995, dawned.

I knew it was Madelene trying to reach me. A quick glance at my watch confirmed that I was late for our prearranged 5:00 A.M. rendezvous. How could I have been so careless on this of all days? After months of secret meetings and cautious planning, had I jeopardized everything at the last minute?

I stole across the wide corridor to the master bedroom, my naked feet silent on the crimson carpet. I was barely breathing as I pressed my ear to the dark lacquered door. I heard only the guttural cough that always punctuated my husband’s all-night cocaine sessions.

Our only hope was that Hyo Jin’s high would render him oblivious for one more morning. For months he had barely noticed as furniture, clothing, and toys disappeared from the second floor of the brick mansion where we lived on the estate of his father, the Reverend Sun Myung Moon, founder of the Unification Church and self-proclaimed Lord of the Second Advent.

It was only a week ago that Hyo Jin’s bloodshot eyes had registered the absence of the IBM computer that usually occupied a corner of Shin June’s room. “Where’s the computer?” he’d asked Shin June, the oldest of our five children. At twelve, she fell all too naturally into the role of coconspirator. Living in the Moon compound — an atmosphere suffused less with spirituality than with palace intrigue — had taught all my children well how to keep secrets.

“It’s broken, Appa; it’s out being repaired,” she replied without hesitation. Her father just shrugged and returned to his room.

I say “his” room because I had long since abandoned the master suite. It was less a bedroom than my husband’s private drug den, its cream-colored carpet littered with cigarette butts and empty tequila bottles, its VCR programmed to play an endless assortment of pornographic videotapes.

I had tried to stay as far away as possible from that room since the previous fall, when I had discovered Hyo Jin snorting cocaine there after so many of his false promises to stop. I tried to flush the cocaine down the toilet. He beat me so severely I thought he would kill the baby in my womb. He made me sweep up the spilled white powder from the bathroom floor even as he continued to punch me. Later Hyo Jin would offer a religious justification for beating half senseless a woman seven months pregnant: he was teaching me to be humble in the presence of the son of the Messiah.

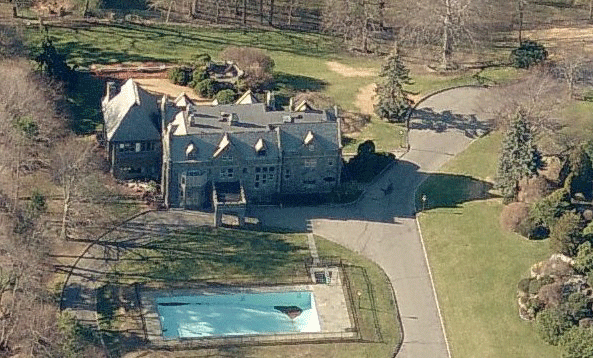

▲ The East Garden mansion with 19 rooms

▲ The East Garden mansion with 19 rooms

The eighteen-acre secluded compound where we lived in Irvington, forty minutes north of New York City, is the world headquarters of the Unification Church and the home of the founder of the religious movement the world knows as “Moonies.” The estate, called East Garden, had been my personal prison for fourteen years, since the day the Reverend Moon summoned me from Korea to be the child bride of his eldest son, the heir to Moon’s divine mission and earthly empire. Then I was only fifteen, a naive schoolgirl eager to serve her God. Now I was twenty-nine, a woman ready to reclaim her life. Today I would escape. I would take the only thing holy about this marriage, my children, and leave behind the man who beat me and the false Messiah who let him, men so flawed that I now knew that God would never have chosen Sun Myung Moon or his son to be his agents on earth.

It is easy for those outside the Unification Church to scoff at the idea that anyone would have believed such a thing in the first place. To most of the world, the name Moonies conjures up images of brainwashed young people squandering their lives hawking flowers on street corners to enrich the clever and charismatic leader of a religious cult.

There is some truth in that view, but it is much too simplistic. I was born to my faith. Just as children of more mainstream Christian religions are reared to believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, sent to earth to redeem the sins of mankind, I was taught in Sunday school that the Reverend Moon had been chosen by God to complete Jesus’ mission to restore the Garden of Eden. The Reverend Moon was the Second Coming.

With his wife, the Reverend Moon would sire the first sinless True Family of God. His children, the True Children, would build on that flawless foundation. Members of the Unification Church would be grafted onto the True Family’s pure-blood lineage in wedding ceremonies arranged and blessed by the Reverend Moon, the mass nature of which has attracted so much attention around the world.

Those beliefs, isolated from the theology in which they are embedded and the culture from which they sprang, admittedly sound bizarre. But what of the miracles of Jesus? Or the parting of the Red Sea? Are Bible stories of virgin births and resurrection not equally fantastic? All belief is a matter of faith. If mine was different, it was perhaps so only in its intensity. Is there any faith more powerful, more innocent, than the faith of a child?

But all faith is tested by experience. The Reverend Moon, sinless? The Moon children, flawless? Father— who demonstrated contempt for civil law every time he accepted a paper bag full of untraceable, undeclared cash collected from true believers? Mother — who spent so much time at chic clothing emporiums that her youngest son once answered, “She shops,” when his schoolteacher asked him to describe his mother’s life-work? The eldest son — who smokes, drives drunk, abuses drugs, and engaged in premarital and extramarital sex, in violation of church doctrine? This family is the Holy Family? It is a myth that can be sustained only from a distance.

Accepting the Reverend Moon for the fraud I now know him to be was a slow and painful process. It was only possible because that realization, in the end, did not shake my faith in God. Moon had failed God, as he has failed me and all his idealistic and trusting followers. But God had not failed me. It was to God that I turned in loneliness and despair, a teenager on my knees in a strange house in a foreign land praying for succor. It was God alone who comforted me, a woman-child in the hands of a husband who treated me either as a toy for his sexual pleasure or as an outlet for his violent rages.

God was guiding me now as I surveyed my sleeping children and the suitcases we had been packing clandestinely for weeks. My belief in Sun Myung Moon had been at the center of my life for twenty-nine years, but a shattered faith is no match for a mother’s love. My children had been my sole source of joy in the cloistered, poisonous world of the True Family. I had to flee for their sake, as well as my own.

When I first told the older ones that I would be leaving, not one chose to stay behind, despite what they knew would be the end of the lavish lifestyle they had always enjoyed. There would be no mansion, no chauffeurs, no Olympic-sized swimming pool, no private bowling alley, no horseback riding lessons, no private schools, Japanese tutors, or first-class vacations where we were going.

Outside the walls of the Moon compound, they would not be worshiped as the True Children of the Messiah. There would be no adoring church members to bow down to them and compete for the chance to serve them.

“We just want to live in a little house with you, Mama,” the oldest told me, her humble fantasy mirroring my own.

And yet doubt and unanticipated sadness had kept sleep at bay for most of the night. Long after the household fell silent, I paced the halls and familiar rooms of the mansion, praying and weeping softly. Each time I had closed my eyes, my mind had filled with the questions that had haunted me for months. Was I doing the right thing? Was leaving truly a manifestation of God’s will or was it a sign of my own failure? Why had I been unable to make my husband love me? Why had I been unable to change him? Should I stay and pray that my son, once grown, might one day return the Unification Church to a righteous path?

I had even more pressing fears. Leaving the orbit of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon would render me and my children spiritual outcasts, but would it put us in physical danger, too? If I fled, would the church track me down to silence me? But if I stayed would I be any safer? How many times had Hyo Jin threatened to kill me and the children? If he was high enough on drugs or booze, I knew, he was capable of making good on those threats. He certainly had the guns to do it, a veritable arsenal purchased with church funds that he used to terrorize me and anyone else who got in his way.

I reminded myself that I was not acting hastily. I had been planning for this day since the previous winter when Hyo Jin’s latest, most blatant infidelity roused even the Reverend Moon from his usual indifference. When Father continued to insist that it was I who was to blame for my husband’s sins, that it was my failure as a wife that accounted for his son’s wayward path, I knew I had to go.

I had taken every precaution. I began to save money as soon as I made the decision to flee. I withdrew money from the bank that I had set aside for the children’s education. I held on to every dollar of the thousands in cash Mrs. Moon would periodically hand me for spending money; when she took me to a Jaeger boutique to outfit me for the church ceremony honoring the birth of my baby, I wore the thousand-dollar outfit she purchased with the price tags discreetly tucked out of sight. I returned the clothes for a cash refund the next day.

With the help of my brother and his wife, the eldest daughter of the Reverend Moon, I found a modest house in the Massachusetts town where they already lived in exile from the Moons. I had been envious when they first left the church, and now here I was, a few short years later, relying on them to lead me to the freedom they’d found. I had worried for them just as I had worried for my own parents, members of the elite group of Moon’s original Korean disciples, who had abandoned the Unification Church in disgust around the same time. My parents were waiting in Korea for word from my brother that I was free.

I was so very grateful. Too often I took my brother’s support for granted, even as a child. Even when we disagreed — and we often did — Jin was always there for me. Jin found lawyers to advise me how to protect myself and my children once we were free. Their counsel helped pinpoint the day we would leave. We would flee on a Tuesday because the family court in the Massachusetts county where we would live heard requests from battered women for restraining orders against their abusive partners on Wednesdays.

I tried, too, to protect those I would be leaving behind. Kumiko had been my baby-sitter for five years. She was a devout member of the church from Japan, as was her husband, a gardener on the East Garden estate. For weeks she had watched me pack boxes, but she said nothing. No member would be impertinent enough to question one of the True Family. But for years she had seen the pain in my life first-hand. I worried that she would be called to account when the Reverend Moon learned that we were gone.

A month before we were to flee, I asked Kumiko where she and her husband would most like to live in the world. They wanted to return to Japan, to her husband’s parents. They were aged and he was an only child. They wanted to go home to care for their elders.

I knew that no personnel changes happened in East Garden without the approval of Mrs. Moon, or Mother, as we addressed her. Twenty-three years younger than the ageing Reverend Moon, she is increasingly the power behind the throne. We had never been close, in part because she surrounded herself with influence-hungry sycophants who elevated their own standing by reporting my perceived failures as a wife or mother. Still, long years of experience had taught me how to coax small favors from Mother.

I found myself embellishing the story as I went along. Kumiko’s husband’s parents were not only old in my account, they were ailing. The couple needed to return to Japan to tend to them. I would rather do without a baby-sitter than hold them from their duty. That last point would strike a chord, I knew, with Mother. How often had Father complained that his staff was too large, too expensive to feed and house? One less baby-sitter and one less gardener would be a feather in Mother’s cap. She willingly agreed to let them go, telling me to be certain that Peter Kim, the Reverend Moon’s personal assistant, gave them money for the trip. They flew to Japan two days before we fled.

Another young woman who helped me care for the baby was due to be married soon at home in Korea to a security guard at East Garden. I told her to extend her visit home until October, time enough, I hoped, to put some distance between our flight and her return.

▲ The East Garden house and conference center built on the grounds. The roof leaked.

▲ The East Garden house and conference center built on the grounds. The roof leaked.

Ever since the Reverend Moon had built himself a separate, twenty-four-million-dollar house and conference center on the grounds, we had shared the common areas of the nineteen-room mansion in East Garden with Hyo Jin’s sister In Jin and her family. As luck — or God’s design — would have it, they had gone away the weekend before and had yet to return. Even if In Jin had been alerted that I might be planning to leave, she would never have taken it seriously. Maybe I was trying to scare Hyo Jin into behaving by taking the children away, she would think. Maybe I was trying to teach him a lesson. I would be back. Neither In Jin nor anyone else in the Moon family would have believed that I would leave for good.

The truth is that not one of them knew me well enough to know what I would do. None of them knew me at all. In fourteen years in the heart of the Moon family, no one had asked me what I thought or felt about anything. They ordered; I obeyed. Today I would turn their ignorance to my advantage.

Quietly I roused Shin Hoon. He was nine months old this very morning and such a good baby; he did not cry as I dressed him in a short-sleeved jumper and then gently shook his siblings awake. I cautioned the children to dress silently while I went to meet Madelene.

In the last year, Madelene Pretorius had become my first real friend. Now, at the other end of my beeper, she was an instrument of my escape. Madelene had been lured into the Unification Church ten years earlier during a chance meeting with a Moonie on a fish pier while vacationing in San Francisco. It is a classic church recruitment technique, befriending a young person traveling alone far from home. The conversation is soon steered from pleasantries to philosophy to the church. A successful encounter ends with the tourist agreeing to attend a lecture or meeting. Some of them never go home.

For the last three years, Madelene had worked for Hyo Jin at Manhattan Center Studios, the recording facility the church owned in New York City. She had seen my husband’s cocaine abuse and raging temper firsthand. When I confided my plan to flee, she had offered her help. It was risky. If he knew she had helped, he would turn on her, too.

Hyo Jin was already suspicious of our friendship. Only weeks ago he had come into the kitchen to find us talking quietly over cups of tea. He ordered me upstairs and Madelene out of East Garden. Upstairs, he threatened to break every one of my fingers if I dared to pursue a personal friendship with a church member. Such threats were typical of his controlling and possessive behavior.

I shivered now at that memory of my husband’s efforts to control me. I waved at the gardener and the security guards as I drove alone through the iron gates of East Garden to meet my friend. She was waiting in front of the local deli. I would spirit her back into the compound just as I had been spiriting our belongings out of the estate for weeks. Almost daily, I made my way past the omnipresent security cameras with chairs and lamps, boxes and suitcases. The guards had accepted without question that I was just rearranging furniture and storing old clothes at Belvedere, another Moon mansion down the road. Mrs. Moon did it all the time.

In truth, I had been headed into town to the storage room I had rented to hold the furnishings of a new life. Today it was time for us to go, too. My brother and Madelene were waiting.

The streets of Irvington and Tarrytown were quiet. It was high summer, when tourists in search of the spirit of Washington Irving’s Sleepy Hollow share the countryside with the locals. But it was too early for either to be stirring. I met Madelene on the designated street corner and smuggled her back into the compound under a blanket so she could help me with the children. We would return to this same corner to retrieve her car, rendezvous with my brother, and travel together to Massachusetts in a caravan.

Once we had loaded the last of the suitcases into the van, Madelene and I led five barefoot children on tiptoe past the master bedroom, down the central staircase, and out the front door. Their father never stirred.

Madelene tucked each child into any available crevice in the overloaded van and then slid into the passenger seat, careful to use blankets to conceal the children and herself from view. I eased the van slowly down the long winding driveway, lined with ancient elms, and out the front gate, smiling at a security guard who had taken his post only a few days before. I turned out of East Garden onto Sunnyside Lane. I did not look back.

▲ The entrance to the East Garden Estate showing the guardhouse.

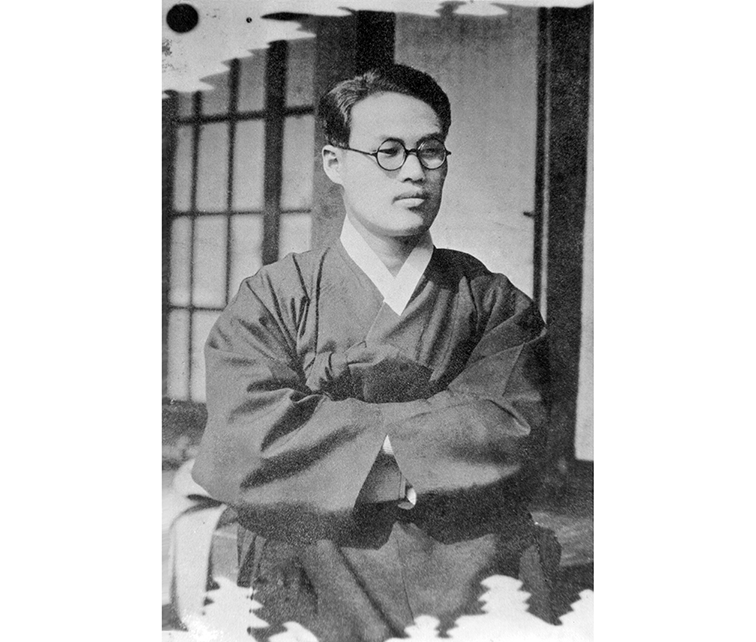

▲ Sun Myung Moon in about 1965

▲ Sun Myung Moon in about 1965

Chapter 1

page 13

The Reverend Sun Myung Moon is a small, compact man with thinning gray hair that he dyes a shoe-polish shade of black. If you passed him on a street in Seoul, you would not notice him, his physical appearance is so nondescript.

He is an electrical engineer by training. His speaking style is notable more for his endurance — he can drone on for hours in Korean — than for his charisma. When he preaches in English, he is barely comprehensible, eliciting unintended laughter on those frequent occasions when he fractures the language.

How, then, did this seventy-eight-year-old farmer’s son emerge as the leader of a religious movement that has ensnared millions of people around the world and enriched itself with the fruit of their labors? The answer has as much to do with the time and place in which the Unification Church emerged as it does with the man himself.

The messianic message of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon might have sounded like the ravings of a madman had it been delivered on a soapbox in New York’s Times Square, but the Reverend Moon sprang from Korean soil, out of the particular circumstances of my country’s spiritual traditions and its turbulent century of foreign occupation, civil war, and political division.

Korea is a land defined by its geography, a peninsula at once attached to and divided from the east Asian mainland by the Everwhite Mountains and the Yalu and Tumen Rivers. Those natural barriers kept my homeland isolated for centuries from the outside world, just as its twenty-six highest mountain peaks kept our people separated from one another. That we managed to forge a national identity and a mutual language is something of a miracle.

When foreign influence did infiltrate Korea, it came from China through the mountain passes of the north and from Japan, whose largest island, Honshu, lies only 120 miles to the east in the Sea of Japan. Because of Korea’s strategic location, its history has been likened to a shrimp buffeted in the battles of whales. Outsiders eager to exploit its seaports and natural resources brought their commerce and their cultures to Korea — and, too often, their guns. They also brought their religions.

The native religion of Korea is a sort of primal shamanism. Shamans, or mudangs, as we call them, are believed to have special powers to commune with the spirit world. They tell fortunes and petition the spirits for blessings, such as a bountiful harvest, or relief from suffering, such as illness. They also commune with the spirits believed to inhabit the forests and mountains, and individual trees and rocks.

When the Chinese introduced Buddhism to Korea in the fourth century, this folklore did not disappear or formalize itself into a distinct religion like Taoism in China or Shintoism in Japan. Koreans merely grafted our ancient beliefs onto Buddhist teachings, which remained the dominant religious influence in Korea until the fourteenth century. Similarly, when Confucianism rose to command a prominent place in religious life for the next five hundred years, it did so alongside that folk tradition, not in place of it.

That process of incorporating native beliefs into other religious doctrines continued in the nineteenth century when Buddhism experienced a resurgence and Christianity was introduced into Korea. Even today, when Christianity is the fastest-growing religion in a still predominately Buddhist country, folklore continues to exert a powerful hold on the imagination of even the most modern Koreans. A Christian who attends church services on Sunday morning might also make an offering to the house god in the afternoon and see no inconsistency.

In addition to ancient beliefs in ancestor worship and the spirit world, there is a strong messianic strain in my culture. The notion that the Messiah or Herald of the Righteous Way would appear in Korea predates the introduction of Christianity into Korea a hundred years ago. It has its roots in the Buddhist notion of Maitreya and the Confucian idea of Jin-In, or the True Man, and in Korean books of prophecy, such as the Cheong Gam Nok.

Likewise, the notion of kings ruling by divine right appears in the country’s earliest legends. As children we all learn the ancient Korean folktale the myth of Tangun. Tangun was the son of the divine spirit Hwan-Ung, who was himself the son of the Lord of Heaven, Hwan-in. According to legend, Hwan-in granted his son permission to descend from Heaven and establish the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. Hwan-Ung came to Korea. There he met a tiger and a she-bear who asked him how they could become human. Hwan-Ung gave them sacred food to eat. The bear obeyed and was transformed into a woman. The tiger did not obey and was forced to remain a beast. Hwan-Ung married the woman, and Tangun was born of this union of a divine spirit and a former she-bear. Tangun established his royal residence in Pyongyang and named his kingdom on earth Choson.

It was in this fertile soil that the messianic ideas of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon took root in the second half of the twentieth century. How much of his official biography is historically accurate and how much manufactured myth is a question I never asked as a child. I absorbed the story of the Reverend Moon in the same way rice absorbs water. From birth I was taught that he was not just a holy man, or a prophet. He was anointed by God. He was the Lord of the Second Advent, the divine guide who would unite the world’s religions under his leadership and establish the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. Denunciations of him by mainstream religions as a cult leader were akin to the persecution of Jesus, whose mission the Reverend Moon was divinely inspired to complete.

The Reverend Sun Myung Moon was born Yong Myung Moon in a rural village of North P’yongan province in north-west Korea, three miles from the coast, on January 6, 1920, the fifth of eight children. His birth name translates as Shining Dragon. This became a problem later in life. Because the dragon is a symbol of Satan, he changed his name to Sun Myung Moon when he became an itinerant preacher.

At the time of the Reverend Moon’s birth, my country was suffering under the yoke of Japanese occupation. Japan had colonized Korea in 1905, an occupation that did not end until after World War II. Christians then composed less than 1 percent of the Korean population, but Christianity developed an ardent following in our stratified society. Protestant missionaries had arrived in Korea from Europe in the mid-1880s. They had survived despite their opposition to ancestor worship, in part because Christianity taught that everyone was a child of God, something of a revolutionary idea in what was still a rigid, feudal society.

Even the aristocracy in the ancient Korean kingdom of Silla was classified according to what was known as the bone-rank system, or golpum-jedo (골품제도, 骨品制度). [It was strictly based on a person’s hereditary bloodline and there was very little chance of social mobility. It thus acted as a caste system. A person’s bone rank governed their official status and the level of authority they were permitted to wield and their marriage rights, and also the color of their garments and the maximum dimensions of their dwelling.] The elite were divided into three classes: the seonggol (성골, 聖骨), or holy bone class, from which the sacred kings sprang; the jingol (진골, 眞骨), the true bone class or the upper aristocracy; and the dupum (두품, 頭品), head classes, which included all other members of the aristocracy. [Below them was the non-privileged general population.] This would influence Sun Myung Moon’s organization of his own religion.

VIDEO about the Korean Bone Rank System

Most Koreans, of course, were poor farmers, not aristocrats. Christianity offered them the hope that if there was no equality on earth, there would be in Heaven. Though small in number, the Christian churches became a center of resistance to the occupying forces. A year before Sun Myung Moon was born, a declaration of independence from colonial Japan was drafted, on March 1, 1919, by a coalition of Protestant ministers, Buddhist monks, and leaders of the many messianic religious sects then gaining popularity in Korea. The signatories were arrested and jailed.

Despite that setback, many Christian leaders — those who did not collaborate — stepped up their agitation for an end to Japanese occupation after the colonial government imposed Japanese as the national language of Korea and established the Shinto shrine in 1925. Korean schoolchildren were required to acknowledge the divinity of the Japanese emperor and to attend sacred rites for his ancestors. Every Korean family was ordered to erect a Shinto shrine in its home. Two thousand Christians who refused were imprisoned; dozens were executed.

By the time the Reverend Moon’s family converted to Presbyterianism, in 1930, the economic hardship of Japanese occupation was as evident as the religious persecution. Nearly all Korean farmers were tenants. Although they were producing record amounts of rice, most of it was exported to Japan, while the local populace went hungry. Japanese nationals made up only 5 percent of the workforce but they held most of the top industrial jobs. Japanese firms owned 92 percent of the working mines in 1932, for example, but it was Korean miners who toiled below ground and lived in unheated shacks above. Those Koreans fortunate enough to secure positions with the government were restricted to low-level jobs.

Such oppression was the backdrop to Sun Myung Moon’s childhood. He is said to have been a studious and prayerful boy, a devout Presbyterian following his family’s conversion when he was ten. All that changed on Easter morning in 1936, when Sun Myung Moon was sixteen. He had been deep in prayer on a mountainside when, he says, Jesus appeared to him and told him that God wanted him to complete the work Jesus himself had left unfinished on earth. While Jesus’ death on the cross had delivered spiritual salvation to mankind, his crucifixion came before he could complete his mission to bring physical salvation to man by restoring the Garden of Eden on earth.

At first the boy refused to listen, but Jesus persuaded Sun Myung Moon that Korea was the new Israel, the land chosen by God for the Second Coming. It was up to him to establish the True Family of God on earth. The Reverend Moon would later write about this vision: “Early in my life God called me for a mission as His instrument. . . . I committed myself unyieldingly in pursuit of truth, searching the hills and valleys of the spiritual world. The time suddenly came to me when heaven opened up, and I was privileged to communicate with Jesus Christ and the living God directly. Since then I have received many astonishing revelations.”

Sun Myung Moon never had any formal theological training. Two years after his original vision, he went to Seoul to learn electrical engineering and from there to Japan in 1941 to continue those studies. [In his Autobiography, Reverend Moon confirmed that he went to a Technical High School which was associated with Waseda University in Tokyo. He did not go to Waseda University, and his name is nowhere to be found at the university. The architect, Mr. Aum, who was a student friend of Reverend Moon’s in Tokyo, explained in his testimony that they both worked during the day to pay for their tuition. Reverend Moon only attended evening classes from 6-9:30pm. In his speeches Reverend Moon has declared that he went to Waseda University, and the Unification Church of Japan even produced a fake Waseda University graduation certificate. In Tokyo] according to church historians, he joined an underground movement to work to end the occupation of Korea. He continued his personal search for truth by traveling into the spirit world himself to speak directly to Jesus, to Moses, to Buddha, to Satan, and to God himself. How he accomplished this transfiguration is one of Unificationism’s mysteries.

❖ Additional Information

Due to the war, Reverend Moon’s education in Tokyo was shortened by six months. He graduated from the Technical High School on September 18, 1943. After 30 months in Japan, Reverend Moon returned to Korea. By studying Electrical Engineering, Reverend Moon was exempt from being drafted into the Japanese military. ref. Michael Breen’s book, Sun Myung Moon, the early years 1920-1953.

One of the reasons Reverend Moon’s first wife, Seon-Gil Choi, accepted to be matched to him in December 1943 was that he told her he was a graduate from the prestigious Waseda University. She thought he would have good prospects. Years later she found that he had never been to any university or seminary. Reverend Moon had lied to her. LINK

The Reverend Moon’s teachings are contained in Divine Principle, a document shaped over many years by the revelations the Reverend Moon says he received through prayer, study of the Bible, and his own conversations with God and the great prophets. Divine Principle is the central text of the Unification Church, but it was not actually written by Sun Myung Moon. Hyo-Won Eu, the first president of the church and one of the Reverend Moon’s earliest disciples, wrote Divine Principle based on the Reverend Moon’s notes and their conversations about his revelations.

Kwang-Yol Yoo, a Unificationist biographer, writes that the Reverend Moon could not transcribe his divine revelations fast enough. “He wrote very fast with a pencil in his notebook. One person beside him would sharpen his pencil, and he couldn’t follow his writing speed. By the time Father’s pencil got thick, this next person could not sharpen another pencil, he wrote so very fast. That was the beginning of the Divine Principle book.”

❖ Additional Information

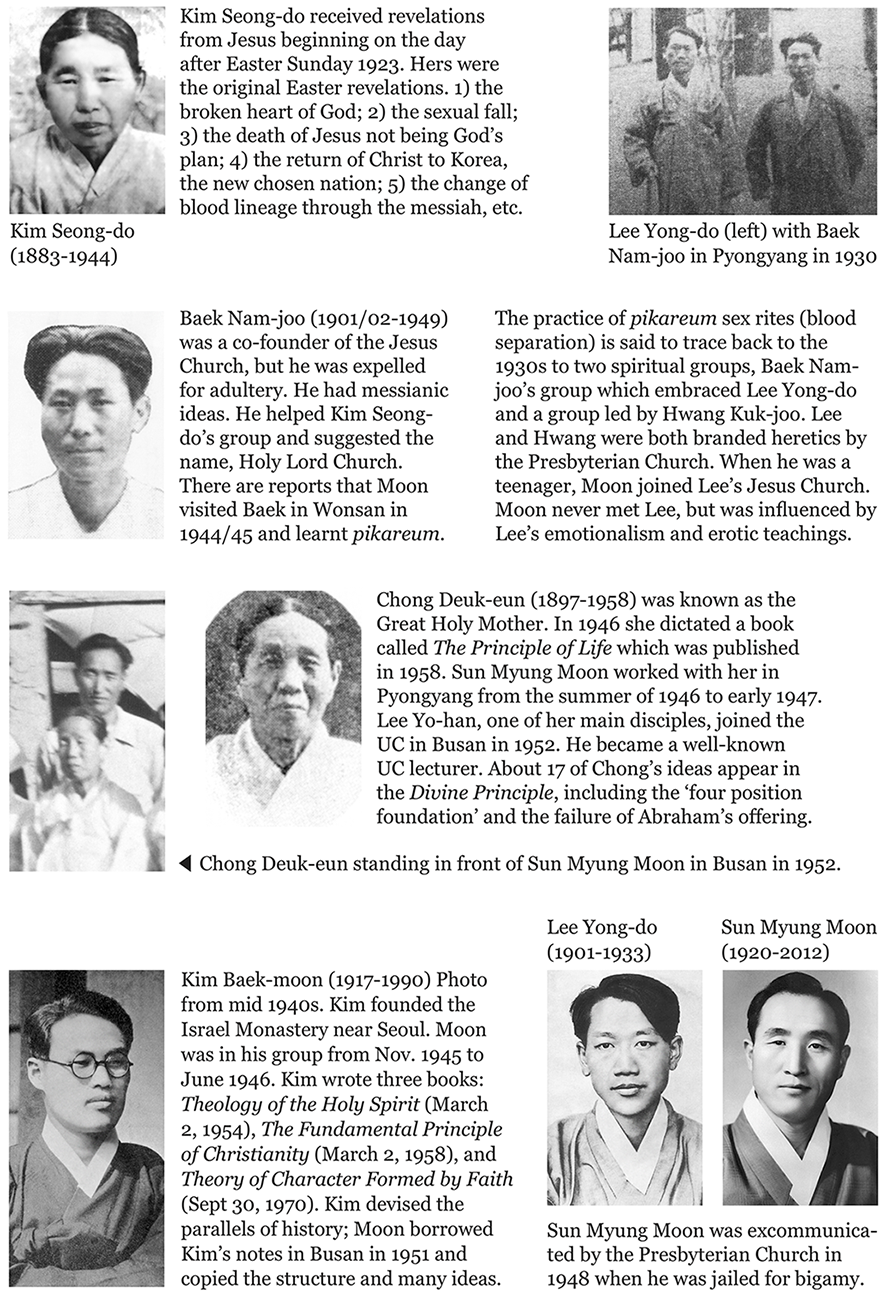

▲ Here is a chart of some of the small spiritual groups active in Korea from the 1920s. Rev. Moon studied the ideas of all of them. Baek Nam-joo taught about the three ages of providential history. Rev. Lee Yong-do heavily influenced both Rev. Moon and Miss Kim Young-oon. She had met him in person; Rev. Moon did not, but he did join Lee’s church as a teenager and a pastor from that church performed his marriage to his first wife, Choi Seon-gil. Kim Baek-moon devised the parallels of history which culminated in 1917, the year of his own birth. LINK

For a heavenly inspired document, Divine Principle is awfully derivative. The 556-page sacred text of the Unification Church is a synthesis of Shamanism, Buddhism, neo-Confucianism, and Christianity. It borrows from the Bible, from Eastern philosophy, from Korean legend, and from the popular religious movements of the Reverend Moon’s youth to stitch together a patchwork theology, with the Reverend Moon at its center.

The modern roots of the Unification Church can be found in Ch’ondogyo — the religion of the Heavenly Way — originally called Tonghak, or Eastern Learning, a nineteenth-century sect closely tied to Korean traditional religion. Like the Unification Church, Ch’ondogyo taught that every individual’s spirit is created by God, that our souls are everlasting, and that all religions one day will be unified.

▲ The Israel Monastery in Seoul

Even the Unification Church’s central tenet, that the Fall was caused not by Eve’s eating a forbidden fruit but by Eve’s having sexual intercourse with Satan, is not an idea that originated with the Reverend Moon. He was taught that theory in 1945 when he studied for six months with a visionary named Baek-Moon Kim at the Israel Monastery in Seoul. Kim taught that the Garden of Eden could be restored only through blood purification. Eve’s sin, the theory holds, has been transmitted to new generations through Satan’s bloodlines. It was part of Jesus’ mission to purify man’s bloodlines by marrying and producing sinless children. He was killed before he could do what God intended. As a result, Jesus’ death brought spiritual but not physical salvation to the world.

Kim was not alone in this belief. Seong-Do Kim was the founder of the Holy Lord Church in 1935 in Chulson in North Korea. She claimed that Jesus had appeared to her [in 1923] and given her a similar explanation about the sexual nature of the Fall and promised that the new Messiah would return to Korea. She taught her followers that sexual abstinence, even in marriage, was necessary to create an environment pure enough to receive the Lord of the Second Advent. After her death, her followers joined the Unification Church and accepted the Reverend Moon as the Messiah.

Divine Principle acknowledges its debt to the long messianic tradition in Korean religious thought.

The Korean nation, as the Third Israel, has believed since the 500-year reign of the Yi Dynasty the prophecy that the King of Righteousness would appear in that land, and, establishing the Millennium, would come to receive tributes from all the countries of the world. This faith has encouraged the people to undergo the bitter course of history, waiting for the time to come. This was truly the Messianic idea of the Korean people which they believed according to Cheong Gam Nok, a book of prophecy. . . . Interpreted correctly, the King of Righteousness, Chung-Do Ryung (the person coming with God’s word), is a Korean-style name for the Lord of the Second Advent. God revealed through Cheong Gam Nok, before the introduction of Christianity in Korea, that the Messiah would come again, at a later time, in Korea. Today, many scholars have come to ascertain that most of the prophecies written in this book coincide with those in the Bible.

The Unification Church teaches that God chose Sun Myung Moon to fulfill that role. The introduction to Divine Principle, published by the Unification Church in 1973, is explicit on this point. “With the fullness of time, God has sent His messenger to resolve the fundamental questions of life and the universe. His name is Sun Myung Moon. For many decades he wandered in a vast spiritual world in search of the ultimate truth. On this path, he endured suffering unimagined by anyone in human history. God alone will remember it. Knowing that no one can find the ultimate truth to save mankind without going through the bitterest of trials, he fought alone against myriads of satanic forces, both in the spiritual and physical worlds, and finally triumphed over them all.”

The Reverend Moon’s task was to fulfill the mission of Jesus. He would marry a perfect woman and restore mankind to the state of perfection that existed in the Garden of Eden. He and his wife would be the world’s True Parents. They would be sinless, as would their children. Couples blessed by the Reverend Moon would become part of his pure-blood lineage and be assured a place in Heaven.

As individuals, we all have an active role to play in this restoration drama. Before the Messiah can fully establish Heaven on earth, mankind must make amends for the sins of the past. In Unificationist terms, they must pay “indemnity” to compensate God for humanity’s past failures. The Unification Church’s strict rules of behavior — no smoking, no drinking, no gambling, no sex outside of marriage — are designed to help individuals in that task.

“The conclusion of the Principle is that you must make up your own mind to love True Parents more than your own self, spouse or children,” Sun Myung Moon has written. “Ultimately, the True Father is the axis around which all children and posterity are centered.”

The Reverend Moon’s own life is said to be a model of willing sacrifice and patient suffering. According to church historians, he was first arrested in 1945 on a charge of using counterfeit money to buy apples by Communist officials who suspected he was a spy from the south.

When he began his public ministry in Pyongyang, his ideas were rejected as heresy by Christian ministers and denounced by local Communist authorities. It was [June 1946]. The city was occupied by Soviet troops. Korea would soon be formally divided into two states, the Communist North under Soviet domination and the democratic South under the influence of the United States. The Communist authorities are said to have tortured Sun Myung Moon and tossed his body outside the prison gates, where he was retrieved and nursed back to health by one of his early disciples, Won-Pil Kim. The Reverend Moon resumed preaching despite the ban on religious teaching by Communist authorities.

He was not to be free for long. The Reverend Moon was arrested again on February 22, 1948, this time for “advocating chaos in society.” [It was for his bigamy with Mrs Chong-hwa Kim who was married with three children.] He was convicted and sent to Heungnam prison, a hard-labor camp where prisoners often were worked to death. By his own account, as prisoner no. 596, the Reverend Moon was underfed and overworked, filling hundred-pound bags with fertilizer and loading them onto railroad cars. The ammonium sulfate in the fertilizer burned the skin on his hands, but he never complained during his two years and eight months in the camp. [Mrs Chong-hwa Kim was also jailed, and never wanted to see Sun Myung Moon again.]

“I never prayed from weakness. I never asked for help. How could I tell God, my Father, about my suffering and cause his heart to grieve still more. I could only tell him I would never be defeated by my suffering,” he wrote.

The roots of the Unification Church’s adamant opposition to international Communism are grounded in the Reverend Moon’s personal experiences. His anti-Communist political beliefs would become a fundamental tenet of his religious philosophy. Those convictions would align him with the anti-Communist governments of South Korea, no matter how oppressive, for the rest of the century.

While he was imprisoned, North Korea invaded the south, provoking the civil war that led to the formal political division of the peninsula. United Nations forces pushed Communist troops north of the thirty-eighth parallel, and in October of 1950, UN troops liberated Heungnam prison, one day before Moon claims he was scheduled to be executed. [Only political prisoners were executed. Moon had been jailed for bigamy and was not listed for execution.] When he was freed, the Reverend Moon and two disciples, Won-Pil Kim and Chung-Hwa Pak, began the long journey to South Korea on foot. According to church legend, the Reverend Moon carried Pak on his back for hundreds of miles after Pak injured a leg. [He had a fractured bone in his ankle.] A grainy photograph of this feat is something of an icon in the Unification Church.

❖ Additional Information

▲ This is not Sun Myung Moon or Chung-Hwa Pak. It is a man carrying his father across the Han River at Chungju on January 14, 1951 during the Korean War. (Photo by JJ McGinty, US Army)

▲ This is not Sun Myung Moon or Chung-Hwa Pak. It is a man carrying his father across the Han River at Chungju on January 14, 1951 during the Korean War. (Photo by JJ McGinty, US Army)

After years of using the photograph, the Unification Church / FFWPU acknowledged that the photograph was not of Reverend Moon or of Mr Pak. However, to this day it is used in workshop presentations by top Korean leaders in the FFWPU.

Chung-Hwa Pak explained that his ankle had been fractured by some thugs in Pyongyang. He said that Reverend Moon did carry him, but it was only once or twice, for 300 yards or so up a steep hill. It was never through water. For the first half of the journey south Mr Pak used a bicycle; for the second part down to Kyongju, where he stayed, Mr Pak was able to walk. Reverend Moon and Won-Pil Kim got a ride on a train for the last part of their journey to Busan.

Michael Breen details the journey in his book, Sun Myung Moon, the early years 1920-1953.

The Reverend Moon settled in the port city of Busan in 1951, building his first church by hand on a small hillside. With a dirt floor, mud walls, and a roof constructed from wood scraps and army ration boxes, the church was little more than a mud hut. The city was crowded with soldiers and refugees displaced by the war. The Reverend Moon worked by day as a dock laborer and resumed his preaching at night.

The Reverend Moon’s official biographers skip over the fact that Sun Myung Moon had married in [1944 at the age twenty-four. He got engaged to Seon-gil Choi in December 1943. It was an arranged marriage – his 24th matching! (see diagram below) They started married life in May 1944, but their legal marriage was not until April 28, 1945.] His wife gave birth to a son, Sung Jin, [two years] later. They were living in Seoul on June 6, 1946, when the Reverend Moon went to the marketplace to buy rice. En route, he now says, God appeared to him and instructed him to leave immediately for northern Korea to preach. Sun Myung Moon, who teaches that he is the ideal Father of all God’s children, abandoned his wife and three-month-old son without explanation. They did not see or hear from him again for six years.

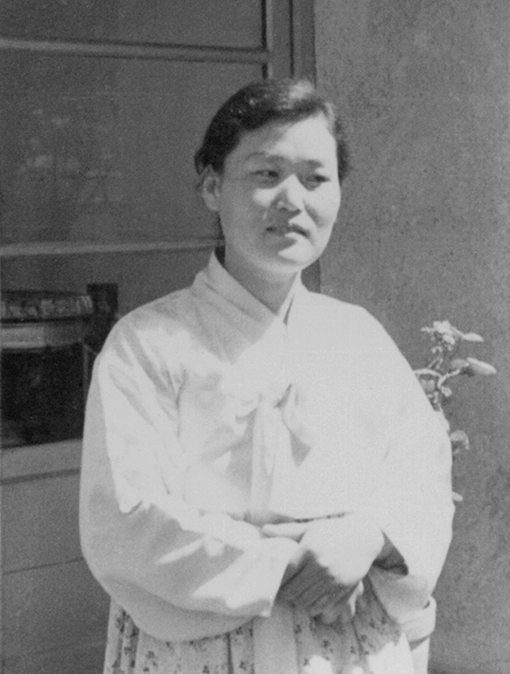

▲ Seon-Gil Choi in Seoul in about 1954-55. She born on March 21, 1924 or 1925 in Chungjoogoon, Pyungbook as the last daughter among six children. She died from an illness on November 16, 2008.

▲ Seon-Gil Choi in Seoul in about 1954-55. She born on March 21, 1924 or 1925 in Chungjoogoon, Pyungbook as the last daughter among six children. She died from an illness on November 16, 2008.

It was not until the Reverend Moon arrived in Busan with his disciples in 1951 that Seon-Gil Choi was reunited with her husband. They did not stay together long. His wife and son moved with the Reverend Moon to Seoul in 1954, where he founded the Unification Church, known formally as the Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity, but the marriage soon broke up. The Reverend Moon dismisses this marriage in a single sentence: “With the Christian people opposing our movement, my first wife was influenced and, being weak, that caused the rupture in my family and I got divorced,” he has written. It was as though Seon-Gil Choi and their son, Sung Jin, ceased to exist.

“Rev. Moon’s wife became increasingly unhappy with Rev. Moon’s dedication to the members who joined his movement, and finally demanded a divorce,” Hendrik Dijk wrote in an internal history of the church. “Rev. Moon did not want this, but finally the situation became irresolvable, and he granted her the divorce. She was in the position to follow him, but found herself unable to do so. She also differed with him theologically and thought the Messiah would return on the clouds. She was strongly influenced by the negativity of the Christian churches.”

❖ Additional Information

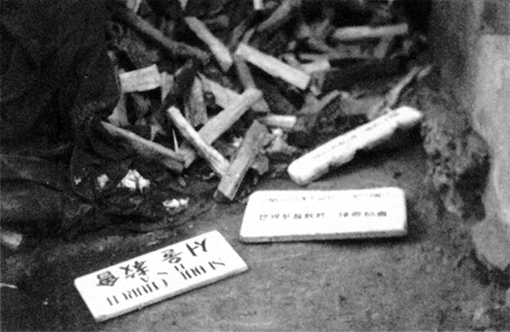

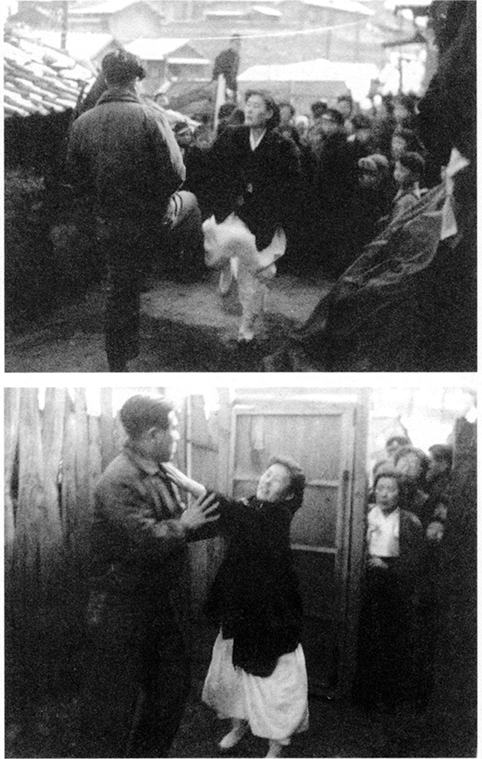

Choi Seon-gil found Reverend Moon doing pikareum sex with two young women at the church in Seoul. She went back home and got the baseball bat which Moon kept there and she used it to smash the church sign. Moon came out and started to fight with her in the street. These photos were taken by Hyo-min Eu, probably in the winter of 1954-55. He explained the story behind the photos.

▲ Seon-gil Choi caught Reverend Moon doing a pikareum sex ritual with two followers. She went home and got the baseball bat which Reverend Moon kept there. She damaged the building and broke the HSA-UWC church signboard. These three photos were probably taken in the winter of 1953/54.

▲ Seon-gil Choi caught Reverend Moon doing a pikareum sex ritual with two followers. She went home and got the baseball bat which Reverend Moon kept there. She damaged the building and broke the HSA-UWC church signboard. These three photos were probably taken in the winter of 1953/54.

▲ Seon-gil Choi fought with Reverend Moon because she could not accept his pikareum sex rituals which went against her strongly held Presbyterian beliefs.

▲ Seon-gil Choi fought with Reverend Moon because she could not accept his pikareum sex rituals which went against her strongly held Presbyterian beliefs.

Reverend Moon had been excommunicated from the Presbyterian Church in 1948. At that time he was jailed for bigamy with Chong-hwa Kim, a married woman with three children, while he was still married to Seon-gil Choi. She eventually divorced him on January 8, 1957.

from the Japanese magazine 週刊ポスト Shūkan Post “Weekly Post”

October 8, 1993

Report by journalist Takeshi Oobayashi 大林高士

A few days later, one gentle woman visited me and pleaded in tears, “Please take this opportunity to tell the members of the Unification Church throughout the world that Sun Myung Moon was never the messiah!”

This woman was in fact the first wife of Sun Myung Moon, Mrs. Seon-gil Choi. According to Pastor Kim, she seemed to be overcome with passion, and she spoke as follows: “After I was married to Mr. Moon, until I gave birth to my son, to my embarrassment I was asked to have sexual intercourse with him more than ten times every night. His energy was that of a serpent, or even much more powerful than a serpent.”

(From the memoirs of Pastor Kim.)

According to the people who knew Mrs. Choi well, she was a chaste and strong-minded woman while she was the first wife of Mr. Moon. Mr. ‘A,’ a former leader of the UC, admitted that he had made Mrs. Choi divorce Mr. Moon. “I made her accept the divorce. She lashed out at Moon who had physical relationships with women, one after another. She became so upset that she went after him, throwing things, breaking the UC sign [outside a church building], and more besides.

Since I was serving as a secretary to Rev. Moon at that time, I just wondered what kind of woman she was. But, looking back on it now, I wonder if she had become mentally disturbed because of Moon’s unusual relationship with women. Now I feel sympathetic towards her.”

Describing the process of the pikareum ritual, Mrs. Choi said that, “Women who had had a sexual relationship with Sun Myung Moon, would then select another man and have a sexual relationship with him. The man, in turn, would then have a relationship with another woman, who would then share a relationship with another man; and, so on and so forth. In other words, the act was carried on as a kind of relay.”

The full interview can be read HERE.

▲ Won-bok Choi, Hak Ja Han and Sun Myung Moon in the 1960s. He liked to keep a baseball bat or heavy stick not too far away.

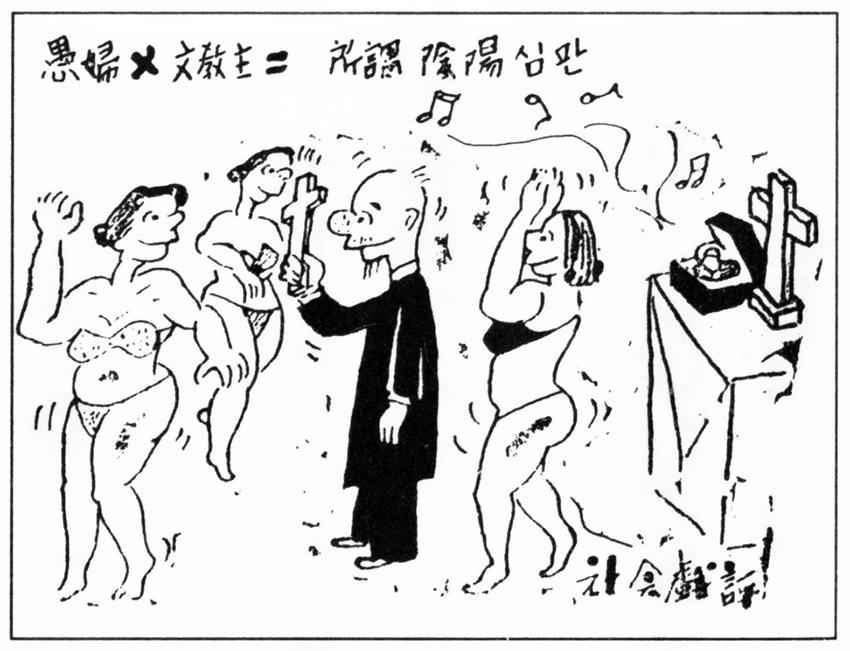

▲ The “pilgrimage to adultery” of Unification Church leader Sun Myung Moon. A cartoon published during the 1955 Ewha University sex scandal.

Text at the top of the cartoon: 「愚婦X文教主 = 所謂 陰陽심판」

“Foolish X Reverend Moon, the so-called Yin-Yang referee”

lower right corner text: 社会戯評 = Social commentary cartoon

ChoongAng Ilbo – Central Daily newspaper, August 3, 1955.

His wife’s departure coincided with the first published reports of sexual abuse in the Unification Church. Rumors were rife that the Reverend Moon required female acolytes to have sex with him as a religious initiation rite. Some religious sects at the time did practice ritual nudity and reportedly forced members to have sexual intercourse with a messianic leader in a purification rite known as p’i kareum. The Reverend Moon has always denied these reports, claiming they were part of efforts by mainstream religious leaders to discredit the Unification Church.

In the early days of the Unification Church, members met in a small house with two rooms. It was known as the House of Three Doors. It was rumored that at the first door one was made to take off one’s jacket, at the second door one’s outer clothing, and at the third one’s undergarments in preparation for sex. There was an apocryphal story of the woman who went to church wearing no fewer than seven layers of clothing, hoping to thwart any attempt to undress her.

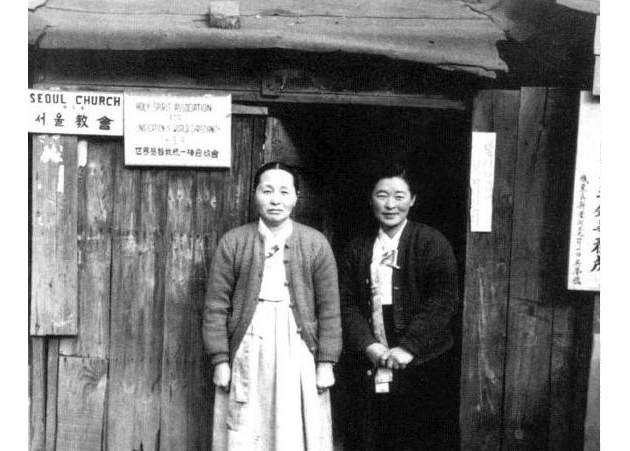

▲ Mrs Ok and Ms Kang standing outside the House of Three Doors in Seoul in 1955. (They were both part of the ‘Six Marys’.)

With these stories in wide circulation in July 1955, the Reverend Moon was arrested for gross immorality and draft evasion. [In court in Seoul on September 21, 1955, Reverend Moon did admit to the judge that he had falsified his age to avoid the draft. He was sentenced to two years in jail.] Both charges were eventually dropped, but rumors persisted that the church practiced p’i kareum.

[In anticipation of the publication of Chung-Hwa Pak’s book, The Tragedy of the Six Marys, official workshops were held in Japan in the early 1990s to explain to the members the theology of p’i kareum. Following the workshops, which were held in a number of cities across the country, some members left. The workshops were terminated.]

Mrs. Gil-Ja Sa Eu, the wife of the first president of the Unification Church — the man who wrote the Divine Principle — was one of five professors and fourteen students expelled from Ewha Womans University in Seoul because administrators there believed the rumors about the Unification Church.

In a speech in 1987, Mrs. Eu traced the origin of those stories back to the Holy Lord Church of Seong-Do Kim. Because they prayed so devoutly, Mrs. Eu said, “many people in that group received that they were being restored to the position of Adam and Eve before the Fall. Therefore, they felt totally purified, with no sin. They said, ‘We are like Adam and Eve, who were naked and unashamed!’ So one time, out of great joy, they took off their clothes and danced naked. This event spread all over Korea and, despite its very remote relationship to the Unification Church, it became one cause for the persecution of our church from other Christians.”

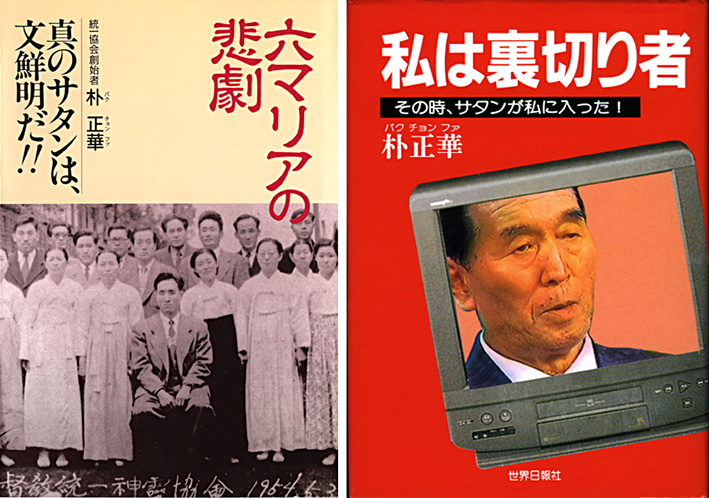

The record of those early days became all the more confused in 1993 when Chung-Hwa Pak, the disciple whom the Reverend Moon is reputed to have carried on his back to South Korea in 1951, published a book entitled The Tragedy of the Six Marys. In it Pak states that the Reverend Moon did practice p’i kareum and contends that the Reverend Moon’s first wife left him because of his sexual activities with other women.

▲ Sun Myung Moon and Chung-Hwa Pak

The Reverend Moon is said by Pak to have impregnated a university student, Myung-Hee Kim, in 1954 while he was still married.

▲ Kim Myung-hee. This photo was probably taken in 1954.

Because adultery was a criminal offense in Korea, the Reverend Moon sent his lover to Japan to give birth. A son, Hee Jin, was born [on August 17, 1955 in Tokyo] and was acknowledged to be the son of the Reverend Moon. The boy would die in a train accident thirteen years later. [On August 1, 1969 Hee-Jin was traveling alone to Maepo station in Chungbuk province. He leaned out of the train and his head was struck by a trackside post.].

▲ Myung-Hee Kim with Hee-Jin Moon in Korea in about 1960. They had returned from Japan in October 1959 after four years of living there in hiding. Hee-Jin reportedly spoke fluent Japanese. Soon she was forced to give her son to Reverend Moon to be raised, not by him, but by other church elders.

Chung-Hwa Pak was persuaded by the Reverend Moon to rejoin the church after publishing his memoir. He disavowed his account of the early days of the Unification Church. I’ve always wondered what the price was of that retraction.

❖ Additional Information

On the left is the book Chung-Hwa Pak wrote: “The Tragedy of the Six Marys – the real Satan is Sun Myung Moon!!” On the right is the book ghost written and published by the Unification Church of Japan. It has the catchy title: “I Am A Traitor – At that time Satan possessed me!” The photograph of Pak which the Moon church chose to use is deliberately very unflattering. The TV is a reference to an excellent news segment produced by Japanese TV on the publication of The Tragedy of the Six Marys book. They also interviewed many people and showed evidence of Sun Myung Moon’s sex rituals, including the testimony of one married woman who had had a ‘womb cleansing’ sex ritual with Reverend Moon. (LINK below)

Since the UC failed to suppress the publication of the Tragedy book by legal means because it was all true, they countered it by producing a propaganda book full of untruths.

These two photographs are very revealing.

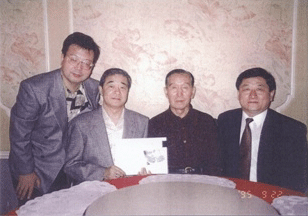

▲ The date on the photo is September 22, 1995. Left to right: Unknown, 石井光治 Mitsuharu Ishii, Chung-hwa Pak and possibly Byung-il Ahn of the Korean UC. Mr. Ishii was president of the Sekai Nippo which did the ghost-writing and publishing of “I Am A Traitor.” The location is probably the Nakataya Hotel in Japan.

▲ The date on the photo is September 22, 1995. Left to right: Unknown, 石井光治 Mitsuharu Ishii, Chung-hwa Pak and possibly Byung-il Ahn of the Korean UC. Mr. Ishii was president of the Sekai Nippo which did the ghost-writing and publishing of “I Am A Traitor.” The location is probably the Nakataya Hotel in Japan.

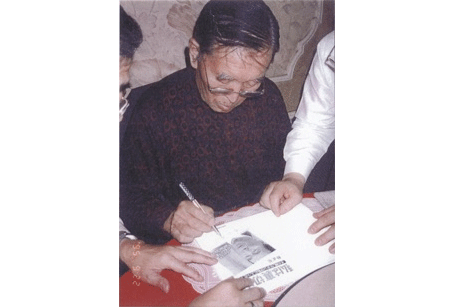

▲ Mr Pak was pressured to co-operate with the very organization whose history he had carefully documented for decades. He had 6,000 pages of notes and had a very good memory. Here he is seen signing his approval for the cover artwork for “I Am A Traitor – At that time Satan possessed me!” (He was unable to use his left arm due to a stroke.) The artwork he is signing is here:

▲ Mr Pak was pressured to co-operate with the very organization whose history he had carefully documented for decades. He had 6,000 pages of notes and had a very good memory. Here he is seen signing his approval for the cover artwork for “I Am A Traitor – At that time Satan possessed me!” (He was unable to use his left arm due to a stroke.) The artwork he is signing is here:

The book was published by the Unification Church of Japan in January 1996.

The book was published by the Unification Church of Japan in January 1996.

Please see Chung-hwa Pak did not write “I am a Traitor” for further details.

My own parents saw no evidence of sexual misconduct when they were each recruited independently to join the church in Seoul. By 1957 the Unification Church had a presence in thirty Korean cities and towns. Though they came from different places and disparate backgrounds, my parents were attracted to the Unification Church out of the same sense of idealism. Religion had not been central to the life of either of them as children. They were like so many young Koreans in the late 1950s, reeling from civil war and searching for a way to help their divided, destitute land. My mother and father, each in their own way, were looking for a purpose in life larger than themselves.

My father, Sung-Pyo Hong, joined the church in 1957. He had been sent to the city by his parents, to study pharmacy, from the small town of Ok-Gya, South Cholla province, where his family grew rice and barley on a small farm. That farm, according to tradition, would be inherited by his older brother. He and his three sisters would make other lives for themselves.

He liked the city. He was a good student and a grateful son, so he was torn when his parents expressed their disapproval when he told them of his interest in a new religious sect. He had been recruited into the Unification Church, as most new members are, on the street. He and a friend were invited to attend a lecture by one of the Reverend Moon’s early disciples. My father came away intrigued.

Soon he was attending lectures regularly and acting as caretaker for the church. During summers and school holidays, he went out preaching, trying to recruit new members. He worked tirelessly for the Reverend Moon, but he did not give up his studies, as so many recruits do.

My mother, Gil-Ja Yoo, had grown up in Gil-Ju in what is now North Korea. Her family was part of the mass exodus of refugees who came to South Korea in the 1940s. She was studying for her college entrance examinations when she, too, was invited to attend a lecture at the Unification Church. A religious life was not what she had planned. My mother was a talented classical pianist and dreamed of a career on the concert stage.

Her parents were even more adamant in their opposition to the Reverend Moon and his church than my father’s family. My grandmother was especially fierce in her disapproval. She forbade my mother to go to church. My mother, nonetheless, would sneak out of the house to attend services. More than once, she was caught and beaten by one of her brothers as punishment for her defiance.

Most Koreans were like my grandparents; they considered the Unification Church a bizarre, if not dangerous, cult. In 1960 their concerns were heightened when the Reverend Moon selected the bride who would serve as True Mother to the family of man. Hak Ja Han was only seventeen years old when the forty-year-old Reverend Moon chose her to be his wife. Her mother had been a devout follower of Seong-Do Kim and believed the Reverend Moon to be the Lord of the Second Advent. She was happy to give her daughter for God, to become the True Mother of the True Family.

“The fall of man can be condensed into one sentence: human beings lost their parents,” Sun Myung Moon has written of Adam and Eve’s being cast out of the Garden of Eden.

“The history of man has been a search for parents. The day people meet their True Parents is their greatest day because, until then, everyone is like an orphan living in an orphanage. You have no place to call true home.”

The Reverend Moon never spoke to me about his own father, but he spoke with great respect for his mother and her capacity for hard work. His cousin remembers True Father as the smart, favored child of six daughters and two sons. Two other babies, a set of twins, had died in infancy. Young-Ki Moon, one of the Reverend Moon’s cousins, spoke at a memorial service in Korea in 1989 commemorating the birth of Kyung-Kye Kim, the Reverend Moon’s mother. His cousin recalled the Reverend Moon as “very mischievous when he was a boy. One day when he was six years old big mother spanked him so much that he nearly fainted. I think after this incident big mother was shocked and I never heard her scolding him again.”

It was his mother who recognized Sun Myung Moon’s intellectual gifts, according to his cousin. She was desperate for him to have a university education. “He had to go to Japan for further study but there was no money to send him, so he had to return to his hometown,” his cousin recalled. “Big mother wanted to sell the land that was in my father’s name to pay True Father’s tuition in Japan. Since all the land was in my father’s name, she couldn’t sell it. So she told me to borrow my mother’s stamp so that she could sell the land and send True Father to school in Japan.” This deceit was part of God’s plan for the Messiah. In order to support the divine plan for the Messiah, others in the Moon family had to suffer.

Hak Ja Han’s childhood had centered on the spiritual movements with which her mother identified. She led a sheltered, protected life on Jeju Island until 1955, when she and her mother moved to Seoul. She was reared by her grandmother, her mother being so engrossed in her own religious life. Her father had abandoned the family when she was still small. [Mr Han was already married. Hak Ja Han has several half-siblings.] When Hak Ja Han was eleven years old, her mother became cook to Sun Myung Moon. Hak Ja Han was still a child when the Messiah first met her and made his decision to marry her.

As the Reverend Moon later recalled,

Women of the early Unification Church wanted to love me at the risk of their lives, coming to see me even late at night. So people gossiped about us. The women didn’t even know why they made such visits to a man who they knew remained centered on God. And when the Holy Wedding came, even the elderly widows wanted to be able to stand in the position of Mother. Some women even claimed to be the True Mother, their eyes shining with confidence. An old lady of 70 years said she would become my wife and bear 10 children! Of course, she didn’t know why she was saying such things. Women with daughters prayed to God with deep sincerity and said they received revelations that their daughters would become the True Mother.

But the woman who would become the True Mother appeared unexpectedly. She was a person whom few had met. . . . I was 40 and about to marry a 17-year-old girl. If this were not God’s will, who could be crazier than I? Just imagine, from that time on Mother’s great responsibility was to carry all the burdens of the Unification Church. Many wonderful, college-educated women were lining up and listing their qualifications, but I shook them all off and chose an innocent 17-year-old girl as Mother. What a surprise it was! Old ladies and mothers exclaimed and rolled their eyes!

Youth should not be a barrier to marriage, the Reverend Moon told his followers: “As soon as you notice your child is an adolescent and aware of sex, they are blessed in marriage. Why should they fall? God, or Heaven, is responsible to each person on Earth to feed, to educate, and to marry. Nowadays, people work hard and yet do not have enough food. People are ready to marry but they cannot. . . . Why should someone be left after one has started to have the impulse of love? It is the parents’ responsibility to determine the proper time.”

▲ The bride, Hak-ja Han, dancing with Lord of the Second Advent, Sun Myung Moon, after the “The Marriage of the Lamb” ceremony in 1960.

▲ The bride, Hak-ja Han, dancing with Lord of the Second Advent, Sun Myung Moon, after the “The Marriage of the Lamb” ceremony in 1960.

Sun Myung Moon and Hak Ja Han were married on April 11, 1960, at the church’s headquarters in Seoul. A dozen members had recently left the church, carrying stories about the Reverend Moon’s claim to be the Messiah and his practice of personally choosing marriage partners for his disciples. There were protests from the outraged parents of church members on the street outside as Sun Myung Moon and Hak Ja Han were joined in holy matrimony.

The opposition was as providential as the wedding, in the Reverend Moon’s view. “Jesus was persecuted by the nation, by the priests, by everyone. Unless we are in the same situation as Jesus was, the restoration cannot be done. This is why the entire Korean nation was mobilized to persecute us. We held the Wedding while hearing voices opposing us from outside the gates. By doing this, the Unification Church gained the victory in the midst of battle. If we had not done so, God would not have rejoiced.”

▲ From the left, Young-Whi Kim, Hyo-Won Eu and Won-Pil Kim with their wives. Reverend Moon and Hak Ja Han are standing behind them.

A week later, the Reverend Moon joined his three closest disciples — Won-Pil Kim, Hyo-Won Eu, and Young-Whi Kim — in marriage to church women he had selected as brides for them. These weddings were followed within a year by thirty-three more arranged marriages, my parents’ among them. The Reverend Moon had given my father the option of selecting his own bride, an unusual opportunity because the church teaches that marriage is a spiritual union that should not be influenced by such distractions as physical attraction. My father deferred to the Reverend Moon’s judgment.

My parents did not know one another when the Reverend Moon made the match, but both were trusting when he said that he had paired them because he knew they would have children who would bring credit to them and to the Unification Church.

When my grandmother got wind of the pending nuptials, she hid my mother’s shoes and locked her in her room. My mother appealed to her younger brother to help her. He found her shoes and unlocked the door. She ran all the way to church. My grandmother was not far behind. She was, however, too late. By the time my parents heard her shouting and banging on the doors of the church, the Reverend Moon had already blessed their marriage.

The Reverend Moon has never forgotten how my grandmother burst into the church that day, beating on his chest with her fists, denouncing him for marrying off her daughter to a man she did not know, in a church she did not trust. Over time, Sun Myung Moon and I both came to believe that I had inherited my grandmother’s spirit.

▲ Reverend Sun Myung Moon did not find an acceptable match until his 24th attempt. Finally the 18 year-old Seon-Gil Choi agreed to marry him after hearing he was a graduate from Waseda University in Tokyo. That turned out to be a lie.

▲ Reverend Sun Myung Moon did not find an acceptable match until his 24th attempt. Finally the 18 year-old Seon-Gil Choi agreed to marry him after hearing he was a graduate from Waseda University in Tokyo. That turned out to be a lie.

This slide is from a presentation by FFWPU elder, Reverend Jin-Hun Yong of the Education Department.

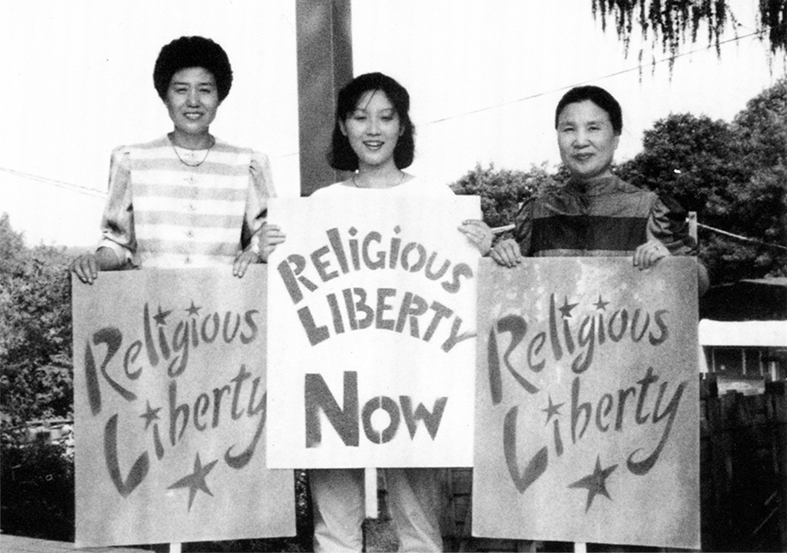

▲ I am flanked here by my mother, Gil Ja Yoo Hong, on the left, and an assistant to Mrs. Moon, Malsuk Lee. Our placards protest the incarceration of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon in Danbury Federal Penitentiary for tax evasion.

Chapter 2

page 33

My earliest memory is of a small, dark room at the end of a long, narrow hallway. If there are windows, I can’t see them in my mind’s eye. If there are furnishings, I can’t envision them. I see only a tiny version of myself, seated on the bare floor, encircled by darkness.

I am alone. The house is empty, but, curiously, I am not afraid. What I am feeling is closer to resignation, an odd emotion to associate with a little girl not much bigger than a toddler. But that’s what I felt even then, that my place in the world was fated and that my role in life was to endure.

I don’t know who I am waiting for — my brother to come home from school, a baby-sitter to come from church — but I do know who I do not expect to see coming down that long, narrow hallway. My mother was away for most of my childhood. I spent my earliest years missing her with a longing that was deep and unarticulated, a physical ache in the hollow center of my heart. Like my father, she was filled with the passion of a freshly minted religious convert. As the first disciples of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon, my parents saw it as their mission to spread the word that the Lord of the Second Advent had come and to recruit new, even more impassioned members for the fledgling Unification Church.

Children complicated that mission, even as our very existence was an expression of it. The Reverend Moon instructed the original thirty-six Blessed Couples to have as many children as possible in order to build the foundation of the True Family of God. He expected them simultaneously to travel throughout Korea, and eventually the world, preaching and “witnessing” on his behalf. The Reverend Moon taught his followers that God would take care of their children if his followers took care of him. The urgency of the Reverend Moon’s mission superseded the personal bond between mother and child.

It was my parents’ religious duty to bring us into the world, but from an early age I knew that their first responsibility was to the Reverend Moon, not to us. They fed us. They clothed us. They sheltered us. I know that they loved us. But the one thing that children most crave — their parents’ time and attention — ours could not give to us.

I was the second of seven children born to Gil-Ja Yoo and Sung-Pyo Hong within the first twelve years of their marriage. I was born on a bedroll on the floor of our maternal grandmother’s small house in Seoul. My grandmother had never forgiven her daughter for joining what she and most Koreans thought to be a crazy religious cult, but she never turned my mother away.

The church itself had no money to share, so the Reverend Moon sent his disciples across the country fortified with little more than their own fervor to survive. My parents did not travel together. To maximize their impact, the Reverend Moon ordered his disciples to spread out, to witness alone. My mother and father would set off in separate directions to Korea’s small towns and even smaller villages.

We would be left to the care of our grandmother, an assortment of aunts, or the women we called the sisters, unmarried church members who served the Reverend Moon by baby-sitting the children of married disciples. Once I had my own children, it was even more difficult for me to understand how my parents could have done this, could have abandoned their babies so completely to the care of others, often strangers. How was this a model of a perfect family?

I do know that my brothers and sisters and I were luckier than some children. Some of the Reverend Moon’s followers simply left their sons and daughters in orphanages in order to preach the word. A few never returned for them.

In 1965 the Reverend Moon described his ideal circumstances for the rearing of children: “We would like to see a boarding house for the children of our members, where some responsible persons could raise them and educate them at least for a few years. This would release you for your necessary witnessing. We have people in our group who are well qualified and willing to conduct such a boarding house and school. This is in the future when we have more money to support such a house and the children. It will be very good for the children, good for the parents, and very good for the movement. No one can enter the Kingdom of Heaven as an individual, but as a family.” He urged his early disciples, my parents among them, to “find people who have the wealth to help us finance such a school.”

Hard as it was for me to be separated from my mother, life was no easier for her. Travel was difficult. She would beg or borrow money for a train ticket, hitch a ride on a hay wagon, do whatever it took to bring the message of the new Messiah into the countryside. Her reward was often the hostility of her audience. Early members of the Unification Church were mocked and stoned, spit upon and jeered. Only occasionally were they heard.

My mother combatted the constant assault on her spirit with fervent prayer. While prayer replenished her soul, it did little for her belly, which was often swollen both with hunger and with child. She lived on rice and water, on the charity of farm women who would see her pregnant profile and take pity on her. I think of the ravenous appetite that marked my own pregnancies and I am amazed at the deprivation my mother suffered in silence.

Her days were long and repetitive. She would rent a room in a village house and spend her days preaching on street corners, her nights lecturing in nearly empty community halls. She had been shy as a girl, but she turned herself during those years into a powerful speaker. She never learned to enjoy the spotlight, but over time she conquered her fear and began to command attention when she spoke.

Poverty and separation were not my parents’ only hardship in the early years of their marriage. When I was still nursing at my mother’s breast, soldiers burst into the small room my family rented in Seoul. The soldiers ordered my father out of the house and, while my mother looked on in terror, marched him off to prison. My father’s crime was failing to register with the army. In Korea military service was compulsory for young men. He had not deliberately evaded his military duty, he told me later. He had been assured that an exemption had been arranged.

The soldiers did not tell my mother where they were taking my father that day. With me in her arms and my two-year-old brother, Jin, in tow, she walked from jail to jail, from police station to station all across Seoul until she found him. It never occurred to my mother to go directly to the Reverend Moon for help. He was too important a figure to bother with her personal problems, no matter how pressing. During my father’s absence, she struggled mightily to keep the three of us housed and fed.