Gifts of Deceit: Sun Myung Moon, Tongsun Park, and the Korean scandal

by Robert B. Boettcher (with Gordon L. Freedman) 1980

Hardcover: 402 pages

Back cover

As staff director of the House Subcommittee on International Relations, Robert Boettcher was in on the Korean scandal from the beginning. It was the investigations done by his staff that led directly to the breaking of that scandal. His work put him in liaison with top officials in the CIA and in the departments of State and Justice as well as with Special Counsel Leon Jaworski and the staff and principals of the Ethics Committee investigation. Fluent in two Far Eastern languages and with an M.S. in international relations from Georgetown University, Mr. Boettcher served five years as a Foreign Service Officer with a specialty in Far Eastern affairs before joining Congressman Donald Fraser’s staff in 1971.

Cover flaps

Gifts of Deceit tells a cautionary tale. It is the story of well-meaning public officials whose anti-Communism was matched only by their credulity; of Congressmen whose self-interests just happened to coincide neatly with the interests of their constituents; of State Department officials who performed their duties with integrity—and were ignored; and of others who dutifully looked the other way at the excesses of a corrupt and brutal regime.

It is the story of a Korean playboy who spent thousands and made millions conning Koreans and Americans alike, and of a Korean government that, through its own Central Intelligence Agency, came close to manipulating American foreign policy even as it intervened in American domestic politics.

It is the story of decent citizens who too readily lent their names and prestige to organizations that were nothing more than fronts for a clever, messianic man —and of decent and bewildered families who lost their children to that same man.

And it is the story, in its fullest account to date, of the origins and operations of the man who calls himself the Lord of the Second Advent and Son of God—the Reverend Sun Myung Moon.

Cool, precise, and factual, Gifts of Deceit makes its message clear: America is vulnerable. Vulnerable to the kind of intervention in domestic politics that was the basis of the Korean scandal. It can happen again — and probably is happening now. And vulnerable to the machinations of a man whose message of Divine Deception has already misled millions and whose political and economic dealings in this country penetrate far deeper than even the most concerned observers had believed.

Here is the book that lays it out, making all the connections—including Moon’s links to the Korean CIA and to high Korean government officials, his support for Nixon and his meddling in U.S. politics, his front organizations and business interests, his manipulation of First Amendment freedoms to protect his cult as it engages in systematic lawbreaking, and the methods he uses to keep thousands in thrall. It is a sad and chilling story.

The ramifications of the Korean scandal are with us still. They are with us because the very flaws and weaknesses that invited the bribery, corruption, and coercion remain —in our institutions, in our public officials. And they are with us, in more immediate ways, in the person of the Reverend Moon —a man whose ambitions are nothing less than cosmic. As Gifts of Deceit unravels the interwoven threads of the Korean scandal, it brings this message home.

Note on Korean Names

Korean custom is to put the family name first, followed by given names; for example, President Park is Park Chung Hee. This book adheres to the custom except in cases of Koreans whose names have become known in this country in the Western order, such as Sun Myung Moon, Tongsun Park, Bo Hi Pak, and Hancho Kim.

Acknowledgments

Significant portions of this book were written in collaboration with Gordon Freedman. Most of the material on Tongsun Park’s activities was derived from his expert investigative work, research, and preliminary drafts. Gordon and I are both indebted to former Congressman Richard Hanna for the very helpful cooperation he gave.

It was my great fortune to have known and worked with Congressman Donald M. Fraser and the staff of his subcommittee’s investigation of Korean-American relations. Throughout our long association, they contributed to the creation of this book in more ways than they could be aware.

In addition to the thousands of pages published on the Korean scandal, a considerable amount of new information was needed. Those who supplied it were both willing and patient with my repeated checking and double-checking. In this regard, I am thankful to Steve Hassan, Lee Jai-Hyon, Ed Baker, Gregory Henderson, Ed Gragert, and An Hong-Kyoon. …

Contents

Prologue 1

PART ONE

1 His Excellency 11

2 The Lord of the Second Advent (with notes) 31

3 The Charmer 56

4 The Origins of the Influence Campaign 78

5 Tongsun and His Congressmen 99

6 Minions and Master (with notes) 144

PART TWO

7 Washington Looks the Other Way 189

8 Three Who Stood in the Way: Ranard, Habib, Fraser 213

9 Koreagate 241

10 Inviting Tongsun Back 267

11 Kim Dong Jo: The Still-Untold Story 290

12 Dueling with the Moonies (with notes) 307

13 The Menace (with notes) 325

Notes 351

Index 389

Prologue

pages 1-8

When Lee Jai-Hyon walked into the conference room on the third floor of the Korean Embassy in Washington, everyone else was already there. He hurried to his usual place near Ambassador Kim Dong Jo’s chair at the head of the long table. Looking around the room, he saw the usual cast of characters: the Counselor for Political Affairs, the Economic Attaché, the Counselor for Commercial Affairs, the Defense Attaché, the Consul General, and the Education Attaché. Seated nearest the ambassador on the left was Yang Doo Won, head of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) in the United States. Lee wondered for a moment if he were the only one with no idea of what the meeting was about. As the Embassy’s chief spokesman, with the title of Chief Cultural and Information Attaché, he was usually told in advance so he could prepare.

With all the senior officials present, Ambassador Kim began to speak. “This meeting will be devoted to sensitive matters of the highest importance to our government. It is therefore necessary to take special precautions for security.” Nothing from the meeting was to be discussed outside the room, he said. Those who attended were not allowed even to talk about it among themselves. As for written records, notes taken during the meeting were to be left on the table and destroyed.

“Does everyone understand?” the ambassador asked. Heads nodded around the table.

Ambassador Kim then turned the meeting over to KCIA station chief Yang Doo Won. Like the American intelligence agency abroad, the Korean CIA had its own organization within the Embassy. And like the American CIA, the head of that unit was called the station chief. Yang Doo Won was known in Washington by an assumed name, Lee Sang-Ho, as was customary for the KCIA in foreign countries. A few months later, when the State Department would quietly tell the Korean Embassy that he was no longer welcome in the United States because of his harassment of Koreans living here, he returned to Seoul under his real name and became Assistant Director of the KCIA.

“We all have a responsibility to retain the support of the United States for His Excellency’s policies,” he began. “The United States is our strongest friend against another attack by the northern puppet.” The term “northern puppet” was standard parlance among South Koreans when referring to North Korea or its leader, Kim Il-Sung. In the same way, North Koreans referred to the Seoul government as “the stooge of American imperialism.” Yang was describing the world as the South Korean government saw it: locked in deadly confrontation between fervent Communists and fervent anti-Communists.

Yang Doo Won went on to praise the wisdom of President Park Chung Hee, newly referred to as “His Excellency,” for promulgating the Yushin Constitution in October 1972, six months before. Yushin, which blocked all criticism of the government, was, Yang pointed out, a necessary step to ensuring national solidarity.

So far, none of this was news to his listeners. It was the standard government line, and any one of them could have made the same little speech, perhaps with varying degrees of enthusiasm.

The KCIA chief was worried, though, about trends in the United States. Americans, he lamented, never hesitated to criticize governments, their own and others. It was the time of Watergate, and Korean officials were amazed by the attacks on Richard Nixon. Although he was confident Nixon would not interfere with Yushin, he was not so sure about Congress and the public.

“Will Americans meddle in our internal affairs by preaching about American-style democracy?” he asked gravely. “What if they condemn the Yushin policy and withdraw their support?”

Yang then asserted the “absolute necessity” for the Embassy to reach out and convince Americans in all walks of life to give “His Excellency” full support. He urged more frequent contacts with Congressmen and other government officials, businessmen with vested interests in Korea, journalists, and university professors. “We must use all such persons for the vital task of enhancing the image of our government if we want to retain American support.”

The meeting ended after about half an hour. No one had said anything from around the table. Lee Jai-Hyon sensed the others shared his puzzlement over Yang Doo-Won’s curious lecture. Never before had there been a meeting where the KCIA did all the talking. The KCIA always worked apart from the rest of the Embassy; there were no day-to-day contacts with its officers in the course of business.

Lee Jai-Hyon was sick of trying to make Park’s dictatorship look good in the United States. He knew the only reason Park had dumped the old constitution was to stay in power. Whatever the KCIA chief was getting at, Lee intended not to be affected by it for very long. He had already decided to resign quietly from government service as soon as he and his wife, a registered pharmacist, could arrange for jobs in Seoul.

In the weeks that followed, there were more secret meetings, never announced more than a day in advance and always with the stringent security measures. During the course of six sessions over a period of about five weeks in the spring of 1973, KCIA intentions came into focus. A conspiracy was being outlined. Bit by bit the pieces of the puzzle fell into place as the KCIA chief, cautiously at first, made words like “manipulate,” “coerce,” “threaten,” “co-opt,” and “seduce” a part of the vocabulary of his talks. After a few meetings, he felt confident enough to declare, “If you know something bad about a person, you can use it to manipulate him.”

The KCIA chief also spoke of “buying off’ Americans. Lee had reason to think that delicate matter was being handled personally by Ambassador Kim Dong-Jo. There had been the incident several months earlier when Lee walked into the ambassador’s office and found him busily stuffing packets of $100 bills into unaddressed white envelopes. Feeling awkward about the strange activity he was witnessing, Lee pretended not to notice and proceeded to raise the matter he had come to discuss. But the ambassador brushed him aside. “I can’t talk to you now; I’m on my way to Capitol Hill,” he said hurriedly. Lee excused himself and left the room.

It seemed to Lee that the ambassador and the KCIA were trying to recruit the whole Embassy. Apparently a lot of manpower was needed. “Front men” and “undercover agents” were mentioned. Lee began to wonder about certain Koreans in the Washington area.

Tongsun Park was one. A wealthy socialite often seen with Congressmen, he obviously had some powerful connections in Seoul. Lee knew Ambassador Kim detested Tongsun but had been told by President Park not to interfere.

For an outsider, Bo Hi Pak was also very close to the KCIA. Lee Jai-Hyon had learned Pak used the KCIA’s secret telecommunications facilities to send messages. At first, it had not seemed important to Lee that Bo Hi Pak was a follower of Sun Myung Moon. In Korea, Lee vaguely remembered Moon as a crackpot evangelist. But Moon had become very active in the United States lately. And there was the time the KCIA had hired some new secretaries on Pak’s recommendation, through the Freedom Leadership Foundation whose founder was Moon.

At the end of April, Han Hyohk-Hoon, Lee’s senior assistant, resigned and went into hiding. That was the beginning of more trouble for Lee.

The Korean Minister of Information, calling from Seoul the day after Han’s defection, told Lee to persuade Han to return to Korea. Lee said there was nothing he could do because the man was already gone.

Things escalated quickly with another call the following night from a very angry minister. “I cannot believe you would hesitate to exert every possible effort to make that traitor return to Seoul. You should be making it clear to Han in no uncertain terms that he must come back at once. That is your duty without even being told,” the minister said.

“I cannot force him to return, Mr. Minister. The American government is processing him for a change in visa status so he can stay here as long as he wishes,” Lee explained.

“That should be no problem for you,” the minister retorted. “You can issue a public statement saying Han is a Communist agent who fled because he knew we were about to catch him after discovering his espionage contacts with North Koreans. The Americans will then turn him over to you gladly.”

It was all Lee could do to restrain his mounting anger. “Mr. Minister, I cannot frame an innocent man. All he did was to leave quietly. He hasn’t denounced the government publicly. And what he tells his friends will do us no harm. I appeal to you: Let him go.”

“I may as well tell you that some of us here are beginning to have questions about your own loyalty. You had better do something to bring Han back or you may be in deep trouble yourself.”

Lee began to worry. What would happen if the government held him responsible for Han’s defection? He wondered whether retirement in Seoul would be safe. He was only a month or so away from announcing his resignation and returning to Korea. But perhaps the plan was no longer workable.

For the next several days there were no calls from Seoul, nor pressure at the Embassy. Instead, the Lee family found itself under surveillance in an unusual way. Embassy colleagues began dropping by the house unexpectedly every night with their wives—not close friends, but casual acquaintances who rarely, if ever, had visited the Lee home. Each couple would stay several hours, and at least one couple paid a “social call” each evening. Both sides—callers and hosts alike—knew exactly what was going on. But both sides, faithful to the rules of Korean etiquette, maintained a pleasant demeanor throughout. To do otherwise would have been unpardonably rude. There could be no personal umbrage, neither taken by the Lees nor intended by the callers. That the callers had been organized to serve as watchdogs over the Lees was a fact lost in the flow of pleasant conversation. So the evenings passed amid the cordial exchange of inconsequential chitchat about the weather, children, the cost of living, mutual friends, and the like, ending each time with the warmest of farewells.

On June 4, 1973, another secret session with the KCIA was held at the Embassy. Lee was still among those invited. This one lasted only about fifteen minutes. As Lee rose from his chair to leave the conference room, the KCIA station chief placed a hand on his shoulder and said, “Dr. Lee, I want to interrogate you in my office now.”

The two men walked together in silence to Yang Doo Won’s office, where another KCIA officer was waiting. Lee Jai-Hyon sat in the chair offered him. Seated behind the desk, Yang slowly read to himself a two-page cable from KCIA headquarters before addressing Lee. The questioning then began, politely but professionally, as if straight from an interrogator’s manual: Name, address, date of birth, family, education, and professional background. Lee felt as if he were in a police station. Then to the crux of the matter:

“Why don’t you cooperate with us to get Han Hyohk Hoon back to Korea? Where is he? Surely you know. Talk to him. Pressure him. If that doesn’t convince him, let us persuade him.” And so forth, returning repeatedly to questions whose answers had not been satisfactory.

Lee recalled stories he had heard about KCIA torture techniques. The interrogation, he realized, was only the first step in breaking him down. After about three hours, the KCIA chief decided to stop for lunch and resume two hours later. Lee Jai-Hyon walked out into the commotion of midday Washington traffic. He never went back to the Korean Embassy again.

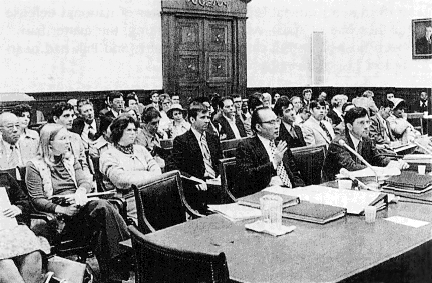

Two years and six days later, on June 10, 1975, Professor Lee Jai-Hyon of Western Illinois University was sitting at the witness table in the cavernous hearing room of the House International Relations Committee in Washington. He had been invited by Congressman Donald M. Fraser of Minnesota, chairman of the Subcommittee on International Organizations, to appear as a witness at one of the subcommittee’s hearings on human rights in South Korea and the implications for United States policy.

The witnesses preceding Lee had given accounts of Park Chung Hee’s repression: torture of political prisoners, mass arrests, prolonged detention without trial, constant surveillance by the KCIA, media censorship, rigged elections, and an emasculated National Assembly.

Concurring with the other witnesses as he took the stand, Lee announced, “I will testify on other aspects that have not yet been touched upon.”

He now felt safe enough to blow the whistle on the KCIA. The time and place were right.

The KCIA’s nefarious activities were not limited to Korea, he said, but also had been exported to the United States in an ambitious plan of clandestine operations based on “seduction, payoff, and intimidation,” to mute criticism of Park Chung Hee’s rule and to buy supporters in the United States. This was something the subcommittee had not expected to hear.

“It took me two years to come here today to tell these things,” Lee declared, “and I am very grateful I can do it here.” He then revealed a detailed plan, drawn from the secret meetings he had attended at the Korean Embassy in 1973.

The KCIA, he said, was trying to “buy off American leaders,” especially members of Congress. American businessmen who had invested in Korea were to be pressured into lobbying for President Park’s policies in Washington. Academic conferences were to be rigged to “rationalize Park’s dictatorship,” and friendly professors were to be rewarded with “free VIP trips to Korea.” The KCIA was to send undercover men into the Korean community in the United States to use newspapers and broadcasting for propaganda, control Korean residents’ associations, and intimidate uncooperative Koreans by threatening the safety of their relatives in Korea.

Congressman Fraser was alarmed by what Lee Jai-Hyon said. If the statements were true, the activities of the KCIA amounted to outright subversion by a supposedly friendly country. He therefore instructed the subcommittee staff to begin making inquiries about Lee’s allegations at the Justice Department and among Korean-Americans. At the time, he had no idea where the inquiries would lead. But in fact, “Koreagate” had begun.

NOTES for Prologue

Pages 1-8

Based on interviews with Lee Jai-Hyon; also his testimony before the Fraser Subcommittee, June 10, 1975, published in Human Rights in South Korea and the Philippines: Implications for United States Policy, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, 1975, pp. 177-185.

Chapter 2 The Lord of the Second Advent

pages 31-55

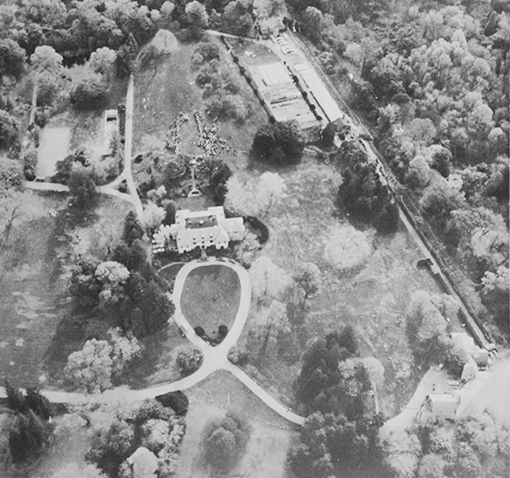

▲ Sun Myung Moon and Hak Ja Han wearing shaman crowns with disciples at Cheongpyeong LINK

Sun Myung Moon leaves no room for doubt about where he and Korea stand in the eyes of God: he is the new Messiah and Korea is God’s chosen nation. This is the culmination of God’s six-thousand-year quest to restore man from the fall of Adam. It was revealed to him by God when he was a young man, Moon tells his cult followers. God said, “You are the son I have been seeking, the one who can begin my eternal history.”

Moon felt no humility. After all, it was God’s will to choose him after an exhaustive search through thousands of years and billions of lives. The title “Son of God” could go to only the rarest of individuals, he says, one capable of winning victory over all human history. He was proud to inherit God’s Kingdom.

Moon’s theology, the Divine Principle, teaches that man can be restored to original goodness by restoring Adam, Eve, and three archangels. Adam’s fall resulted from Eve’s being seduced by the archangel Lucifer, who was jealous because God gave Eve to Adam instead of to him. Human history has been a constant replay of the same interaction among Adams, Eves, and archangels. God’s eternal plan for man’s perfection has been thwarted as potential Adams are undone by Eves and archangels. The positions of Adam, Eve, and the archangels are occupied by persons, nations, and movements identified as such by Moon. Ultimately, Adam must dominate after successfully going through three stages: formation, growth, and perfection. But if an Eve or an archangel is at a higher stage than Adam, they must help restore Adam to perfection so he can assume his rightful role in the unified system of things.

Moon is Perfect Adam, so he must be obeyed without question. Jesus, the most important Adam between the original one and Moon, attained spiritual perfection but was a flawed Messiah. His mission was foredoomed by John the Baptist, who spent his time baptizing people instead of becoming Jesus’ obedient disciple for influencing the politics of the Herod regime. Making things worse, Jesus was a child of adultery, not immaculate conception, according to Moon. Mary was impregnated by Zachariah. Jesus had an unhappy home life because Joseph was jealous of Zachariah and resented Jesus.

The Divine Principle therefore teaches family unity as dictated by Moon. When Jesus grew up he failed as a leader because he was unable to love his disciples enough to motivate them to kill for him or die in his place. Moonies are taught that because Moon’s love is not of the weak Jesus kind, their love for Moon must be strong enough to do what Jesus’ disciples were unprepared to do. Since Jesus was incapable of perfect love, owing to his unwholesome upbringing, he was also unable to marry as intended by God.

“The reason why Jesus died was because he couldn’t have a bride. Because there was no preparation of Bride to receive Jesus, that was the cause of his death,” Moon preaches.

[However, it should be noted that the first version of the Divine Principle, which was called Wolli Wonbon, told a very different story. Moon had written it himself in two notebooks in Busan, completing it in May 1952. In Wolli Wonbon Moon clearly explained that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene. The Jesus marriage narrative was reversed by the time the Divine Principle was first published as a book in Korea in 1957.]

Political action is central to Moon’s mission, although the cult denies that it engages in politics at all. Moon views Jesus’ failure as a political failure for not gaining control of the government of Israel. Jesus was able to establish a spiritual kingdom, but that was only half of what God wanted. Moon is taking up where Jesus left off by uniting the spiritual kingdom with a physical kingdom on earth. The trouble with Christians, he says, is that they have accepted the myth that the Messiah will return as a spirit “on the clouds.” To Moon it is obvious that if this were true, God would have made it happen long ago. The long delay was necessary because God intended for the Lord of the Second Advent to appear as a person who will complete Jesus’ mission on earth among the living. He sees Christian churches as furthering Satan’s cause by rejecting him.

Israel was God’s chosen nation, but the Jews, falling prey to Satan’s power, rejected Jesus. God punished them with centuries of suffering, and finally cleansed them by killing six million in World War II. But the Jews had missed their chance. God had to find a new Messiah and a new Adam nation because, Moon explains, it is God’s principle not to use the same people and the same territory twice. Korea was ideally suited for several reasons. It is a peninsula, physically resembling the male. Like the Italian peninsula, cultures of islands and continents can mingle there to form a unified civilization corresponding to the Roman Empire. Korea had maintained its own cultural identity through invasions by China and Japan over the centuries. And at Panmunjon, the military demarcation line represents the division between not only the Communist and non-Communist worlds, but God and Satan as well.

Japan is in the position of Eve. Being only an island country, it cannot be Adam. It yearns for male-like peninsular Korea on the mainland. Moon sees the Japanese generally as effeminate people who want to be dominated by stronger, manly powers. But as Eve prevailed over Adam in the Fall, Japan prevailed over Korea in the colonial period. And like Eve in the Fall, Japan became a Satanic power.

America is an archangel country. Its mother is England, another island country in the position of Eve. The archangel America helped the Adam country Korea by sending Christian missionaries, rescuing it from Japanese rule, and stopping the advance of Satan’s Adam—Communist North Korea. America is too arrogant and individualistic, however. It cannot remain the world’s leader, because God has destined America to serve Korea.

Korea’s mission, therefore, is to restore the Eve country Japan and the archangel America, and become the center of the new unified world civilization. This is to be accomplished through Moon and his Unification Church.

In Moon’s unification thought, politics cannot be separated from religion. His political views have been conditioned narrowly by South Korea’s two prevailing political phenomena during his lifetime—nationalism and anti-Communism. What he sees as politically imperative for Korea, he has applied to all of God’s universe. World history is now centered on Korea, he preaches, and what happens to Korea centers on him. He claims the Korean War could have been avoided had he been accepted as the Lord of the Second Advent. The archangel America had created the right conditions by making Korea independent from the Eve country Japan. But the Koreans, failing to rally around Moon, were divided between Communist and free-world forces. Though tragic, the division carried forward God’s plan that Korea be the flag bearer for the world. The battlefield for the showdown between God and Satan would be Korea. God’s chosen people would triumph through suffering. America, Japan, and all other nations could be restored by helping Korea’s anti-Communist cause. Only in Korea could the civilizations of East and West be unified. In the end, Moon declares, even North Korea’s Kim Il-Sung could be restored if he answered the call to follow the Divine Principle.

Details about Moon’s early life are not clear because of his efforts to tell the story himself only in terms of being the Son of God. He was born in 1920 in north Korea. He was raised as a Presbyterian in a middle-class family, was a good student, and studied engineering at a [Technical High School] in Japan during World War II. He was married in 1944 and divorced in [January 1957]. He was arrested twice by the Communist government in North Korea for activities as an evangelist and was sentenced to five years in prison in the [spring of 1948]. During the Korean War, when United Nations forces reached Heungnam prison, he was released halfway through his sentence. He resumed his evangelical activities in Busan on the southeastern coast. With a small handful of followers in Seoul, he founded the Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity, which became known as the Unification Church, in May 1954.

Rumors reached the American Embassy that Moon was a ritual womanizer. Reportedly, young girls [from the Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul and elsewhere] underwent sexual initiation into his cult; he would thus purge them of the Satanic spirits that inhabited Eve and lead them to the Divine Principle. In 1955 he was [found guilty and] jailed for [two years, but released late at night after] three months by South Korean authorities on charges reported by newspapers and government agencies as draft evasion, forgery, “pseudo-religion,” and false imprisonment of a university coed [Choi Soon-shil from Yonsei University who was] compelled to adopt his religion. The charges were [suddenly] dropped, and Moon’s followers hotly deny that Master was a fornicator.

Moon’s own account of his life is heavy on allegory supporting the Divine Principle. The episodes he relates to his cult are like parables, always with a direct tie-in to his teachings. He presents his life story as the unfolding revelation of the Divine Principle, with himself as the example to follow for what he preaches.

There was a minister named Kim [Kim Baek-moon in Seoul] who was Moon’s John the Baptist. [Moon started to follow Kim in October 1945.] According to Moon, after Kim received a revelation from God, he placed his hand on Moon’s head and blessed him as the heir to King Solomon and the glory of the whole world. Unfortunately for Kim, the women in Kim’s following—also responding to divine revelations—became attracted to Moon. The rivalry resulted in Moon’s leaving after a short time [in June 1946 when Moon moved to Pyongyang]. But Moon could not hold himself responsible for what happened. When Kim gave Moon his blessing, God rightfully transferred all that Kim had to Moon.

▲ Kim Baek-moon is standing at the back wearing glasses. This photo was taken in the summer of 1946, about the time that Moon was asked to leave. Moon used many ideas from Kim’s theology, including the parallels of history. LINK

God revealed Moon’s divine mission to his fellow prisoners in Heungnam, North Korea, Moon tells. They were in awe of him because he could do twice as much work as they, and on half the rice quota. He thought of half a bowl as his full quota and the other half as an extra gift from God, which he gave to the other prisoners. He disciplined himself to the most distasteful work: carrying 1,300 bags of fertilizer to the scale every day. For the Son of God no amount of labor was too much. Others needed rice for survival, but Moon was living on the spirit of God. While working he imagined he was the star of a movie being shown to his ancestors and descendants. He resolved to teach his followers to ignore the limitations of their physical bodies and be sustained by spiritual strength.

There was a woman named Ho Ho-Bin in prison with Moon the first time he was arrested [in August 1946 in Pyongyang]. Whenever she had divine revelations, her stomach muscles wobbled. This was God’s way of reminding her that the new Messiah would come as a real person from a mother’s womb. Several times Moon tried to contact her, but she refused to have anything to do with him. He wanted to tell her that if she put her faith in him and lied about her revelations, the Communists would release her. Finally he slipped her a note:

“The writer of this note is a man of heavenly mission, and you should pray to find what he is. If you deny everything you have received, you will be released.”

Mrs. Ho would have none of it. She wanted to destroy the note immediately, but the guard, tipped off by another prisoner, grabbed it. Moon was interrogated, accused of being an American spy, and tortured. But he denied her revelations and was released after less than three months in jail. He says Mrs. Ho and all her followers were killed by the Communists when the Korean War started in 1950.

Mrs. Ho’s fate dramatizes the peril of not accepting Moon as the Messiah. Disobeying him led to her death. She refused to follow the Lord of the Second Advent. By disregarding Moon’s counsel, she violated his Doctrine of Heavenly Deception.

Moon teaches that lying is necessary when one is doing God’s work, whether selling flowers in the street or testifying under oath. The truth is what the Son of God says it is. At the Garden of Eden, evil triumphed by deceiving goodness. To restore original perfection, goodness must now deceive evil. Even God lies very often, he says. God’s lies bring far greater gifts than man thinks are possible. If Mrs. Ho had believed in Moon and lied she would have been released. If released, she might have become Perfect Eve with Moon.

Moon claims to have found Perfect Eve in the seventeen-year-old girl he married in 1960, Han Hak Ja. He told the cult that her preparation for Bride to receive Moon began at the age of four; in 1947 she was blessed by Mrs. Ho. Being so young at the time, she did not remember the experience. But Moon was aware of it from the moment he met her. Once the vows of matrimony were exchanged, Moon as Perfect Adam could not let himself fall into the same trap as the first Adam. He “snatched her out of the Satanic world” and taught her to obey. Since Adam fell by being dominated by Eve, he had to reverse the precedent by achieving complete domination over his wife. Obedience training went from formation to growth and perfection, to the point where, after three years, he says, she would sacrifice her life if he so ordered.

Since Adam and Eve fell from grace and Jesus never married, it remained for the Third Adam to restore the Perfect Family. Moon and his wife became True Parents, known as True Father and True Mother.

Only True Parents can consecrate the heavenly marriage needed to create a heavenly home. Before Moon grants permission for Unification Church members to marry, they must serve him for at least three years, corresponding to Jesus’ ministry of three years. Mates are chosen by Moon, often at random in a large group, and couples are not supposed to consummate the marriage until they have Moon’s approval.

In order to rule the world, Moon had to start with Korea. It was essential that he have loyal cultists inside the government. They had to be well placed so they could sway powerful persons and become influential themselves. They must be skillful in portraying the Unification Church as a useful political tool for the government without revealing Moon’s power goals. By Moon’s serving the government, the government would be serving him. Avenues to more power could be opened. Recognition at higher and higher levels could come. His service could become indispensable. The government could come to need him so much that he would be able to take control of it.

Four of his early followers were young army officers close to Kim Jong-Pil, the chief planner for the Park regime and founding director of the KCIA: Kim Sang-In (Steve Kim), his interpreter, later to become KCIA station chief in Mexico City; Han Sang-Keuk (Bud Han), who became ambassador to Norway; Han Sang-Kil, who became Moon’s personal secretary after serving at the Korean Embassy in Washington; and Bo Hi Pak, Moon’s advance man in Washington during and after Pak’s service as assistant military attaché at the Korean Embassy.

Kim Jong-Pil made a two-week official visit to the United States as KCIA director in the fall of 1962. Included in his entourage was Steve Kim as interpreter. The Korean Embassy mobilized for the occasion, and the Kennedy administration rolled out the red carpet. Lieutenant Colonel Bo Hi Pak was the Embassy’s officer in charge for Kim’s meetings with CIA Director John McCone, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and Defense Intelligence Agency head Lieutenant General J. E. Carroll.

En route home, Kim Jong-Pil met secretly in his room at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco with a small group of Moon’s early activists, who had been sent to proselytize on the West Coast, and some American converts. Kim Young-Oon, beginning in Eugene, Oregon, in 1959, had moved to Berkeley, California. Choi Sang-Ik [Papasan Choi], having established the church in Japan, had moved to San Francisco. Kim told them he sympathized with Moon’s goals and promised to help the Unification Church with political support from inside the government. He said he could not afford to do so openly, however, which fit Moon’s plans perfectly.

Kim Jong-Pil had learned from Moon’s followers in the KCIA that Moon was a zealous anti-Communist. That could be useful to the government. He was also aware of Moon’s ambition to build influence in Korea and beyond. That could create problems for the government if the influence were not properly channeled. Moon was anxious to increase church membership in cities and villages throughout the country. Fine, thought Kim, just as long as they don’t get out of bounds. The KCIA must be the one calling the shots. He decided the Unification Church should be organized satisfactorily to be utilized as a political tool whenever he and the KCIA needed it. Organizing and utilizing the Unification Church would be a simple matter anyhow. After the military coup overthrew the elected government in 1961, all organizations in Korea were required to apply for reregistration with the government. Undesirable elements were identified through a process of reevaluation and dealt with accordingly. Kim could maintain effective ties with Moon’s organization through the four army officers, but the Moonies had best not be told of Kim’s plans to manipulate them. It was a situation favorable both to Moon’s plans for expanding via the good graces of the government and to Kim Jong-Pil’s plans for building a personal power base.

Bo Hi Pak’s work for Moon in America was of crucial importance. Pak is a model Moonie. For him, Master always comes first. From the time he joined Moon in 1957, he endeavored to make everything he did contribute in some way to Moon’s divine mission. Assignment to the Embassy in Washington in 1961 was a precious opportunity to do missionary work in the United States. As a diplomat, he could foster Moon’s interests within the R.O.K. government and keep Moon apprised of important intelligence. It was God’s providence that he go to America, he believed, and he must make the most of it.

Pak “witnessed” tirelessly for Moon. Every new acquaintance was a potential convert. His home on North Utah Street in Arlington, Virginia, was a recruiting center. Every social gathering there was a potential study group. He was assisted in his ministry by his wife and another Moonie living with them, Jhoon Rhee [a cousin], who later became well known as the owner of a chain of Korean karate schools. In 1963, Pak established the Unification Church in Virginia. The incorporation papers declared the church to be totally independent from any other organization and affiliated with the original movement in Korea only on a doctrinal basis.

▲ Jhoon Rhee is standing on the left, and next to him is Bo Hi Pak.

Airline pilot Robert Roland and his wife were cultivated patiently by Pak over a period of several months without a hint about the connection with Moon. The Rolands and the Paks became close friends.

On one occasion, Roland asked what the duties of an assistant military attaché were. Pak was candid about his intelligence role at the Embassy. He explained that in addition to routine diplomatic work he was responsible for liaison between South Korean and American intelligence agencies, which often required his visiting the super-secret National Security Agency (NSA) located at Fort Meade, Maryland. Roland asked about the work the NSA did.

Pak volunteered that it dealt mainly with secret codes and monitoring of radio transmissions. Roland, a bit startled by the information, was finding his new friend to be an intriguing person.

One evening, the Rolands found that they were the only guests invited. Previously, others had always been present. As small talk wore on at the dinner table, Roland sensed his hosts were leading up to something carefully planned. When the meal was finished and they were settled comfortably in the living room, Pak revealed step by step how the destiny of mankind was in the hands of a Korean named Moon. Pak’s life was devoted to helping Moon fulfill his divine mission.

“You’ve noticed that I sometimes seem tired and overworked,” he said to Roland. “That is because I am so busy working for Master that I have time for only three or four hours of sleep. My boss at the Embassy criticizes me for neglecting my duties there, but I know the Korean Government favors our movement. If necessary, I would work twenty-four hours a day for Master.”

“What are you trying to accomplish in Washington?” Roland asked.

“I must lay a firm foundation for Master by making influential political and social contacts.”

Roland was curious to know if Moon had remained celibate until he married at the age of forty.

Pak’s expression became serene and he nodded with sincerity. “Yes, most pure virgin.”

It all sounded like fascinating hogwash to Roland, but his wife was taken in. Her devotion to Moon led to divorce years later and estrangement between Roland and their daughter after she, too, became a Moonie. But it was not until many months after that first talk that Roland became outwardly hostile to the movement. In the meantime Pak attempted to convert him, and Roland learned interesting details he was later to use during a thirteen-year effort to expose the Moon organization.

After attending a concert by the Vienna Boys Choir, Pak conceived the idea of organizing a troupe of young girls to perform traditional Korean songs and dances. The propaganda value could be enormous with the right kind of management. Moon could double what the Austrians had done with the Vienna Boys Choir: little girls as ambassadors of good will for Moon and Korea, dancing their way into the hearts of millions, including presidents, prime ministers, and kings. Moon liked the idea and founded the Little Angels in 1962.

▲ The Little Angels with President Park Chung-hee and his wife in 1971

The Little Angels were one of the first of hundreds of “front” groups designed to further Moon’s universal objectives. The groups follow a consistent pattern. Moon may be listed as the founder, but ties with the Unification Church are denied. Moon stays in the background while Moonies such as Bo Hi Pak promote the group for Moon’s ultimate benefit. The technique attracts large numbers of people who are uninterested in Moon’s religion. To the extent that they know Moon is affiliated, they see him as a man with varied worthwhile interests apart from religion. The fact that his religious interests encompass everything he does is artfully hidden from the public. But even while the Little Angels project was still in the planning stage, Pak stated the purpose clearly in the application for tax-exempt status for his Virginia branch of the Unification Church. He wrote in his statement to the Internal Revenue Service: “It is hoped that the future will allow sponsoring a Korean dancing group in various cities as a means of bringing the Divine Principles to more people and to thus further the unification of World Christianity.” As evidence that his organization was a bona fide church, he submitted a letter signed by Korean Ambassador Chung Il-Kwon, which Pak had drafted, certifying that the Unification Church “has been the recognized Christian religion in Korea since 1954.” At the time of the letter, 1963, most Koreans had not yet even heard of Moon’s church.

Added material

New Growth on Burnt-Over Ground by Jane Day Mook, article published in ‘A.D.’ May 1974 pages 30-36

“Both the theology and what are understood as the practices of the Unification Church have been anathema to main-line Christians in Korea. Moon himself was excommunicated by the Presbyterian Church in Korea as long ago as 1948.

His church has not been accepted as a member of either the National Council of Churches or the National Association of Evangelicals in Korea, both of whom state unequivocally that the Unification Church is not Christian.”

The Unification Church sex scandal which involved many female students from the prestigious Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul had been reported in dozens of newspaper articles during 1955. The Unification Church had become notorious and recruitment in the cities had become more difficult, so members were sent out to the countryside to witness. Children of farmers sometimes joined to escape a future of farm work. All the mainstream Korean Christian churches had rejected Moon and his heretical theology. These facts were well known at the American Embassy in Seoul which sent reports about Moon back to the United States.

FBI report dated October 6, 1975:

“He was accused in 1955 of conducting a group sex orgie…”

“A letter prepared by the Church of the Nazarene, Korean Mission, Seoul describes Moon’s official theology, and details what Moon’s church secretly believes and practices:

1) Founder Moon is the Second Advent Jesus.

2) A believer receives a spiritual body by participating in a ceremony known as blood cleansing which is for women to have sexual intercourse with Moon and for men to have intercourse with such a woman. This idea of blood cleansing comes from the teaching that Eve committed immorality with the Serpent and she passes on to all of us serpent blood.

3) Secretly observed doctrines are Holy covenant and are of more value than the Bible.

4) Members who have experienced blood cleansing can produce sinless generation [children].

5) Founder Moon is sinless.”

CIA intelligence reports were among a sheaf of intelligence summaries, diplomatic cables, governmental memorandums and other documents made public by the Fraser subcommittee as it opened four days of hearings on Korean efforts to influence American policy.

The first mention of the Unification Church came in a United States Central Intelligence Agency report dated Feb. 26, 1963…

On the Unification Church, an intelligence report said: “Members of the church are actively engaged in increasing membership in farming villages. The church apparently has considerable money, because it pays influential people in the villages a substantial sum for joining the church.”

The wife of the UC president at the time, Sa Gil-ja, explains further about the 1955 Ewha Womans University Sex Scandal.

She was one of the students who was expelled. Here are some extracts from her April 12, 1986 testimony.

“Most of the 124 Couples are from very poor families, and the reason for this is very important for our members to understand. At the time the Unification Church was established, Korea was a very poor country. There were many children of poor farmers who had very little education, because they had to help their family in the fields. Every day they had to go up the mountains to gather sticks for fuel and carry them back down on their backs.

“In 1955 Ewha [Womans] University and Yonsei University started heavy persecution. Because of this the Korean government, all established churches, and all educated people started to persecute the Unification Church. People even wanted the government to stop the movement, to wipe it out. At that time we could not reach any high-level or educated people, so Father sent us out to the countryside to educate these poor farmers’ children.

“We couldn’t say we were from the Unification Church because of our bad reputation, but we could teach them basic things, such as how to read and write Korean or Chinese or English. Through this they became connected to us and some of these young people eventually joined. They went to 7-day workshop, 21-day workshop, and 40-day workshop. Then they left their parents and their farms and became pioneers for the church.

“Of course, their parents were very angry with them because they needed their children to do the farm labor. The children more or less escaped from their families. As pioneers they were very poor, so sometimes they would try to go back to their parents and beg them for a little rice or some money, in order to be able to continue their mission on the front line. But often their parents wouldn’t give them anything.

“When other church members established companies these members could work there, but because of their lack of education and skill they could take positions only as unskilled laborers at very low wages. Most have only a primary school education, and because of the urgency of the providence, they never had a chance to continue their schooling after they joined. All they had was faith in the Principle.”

http://www.tparents.org/Library/Unification/Talks/Eu/Eu-860412a.htm

In Korea, the Little Angels were getting organized. Instructors were hired, girls were recruited, and the government provided a building free of charge for the training center. But a great deal of money would be needed to elevate the scheme to the level intended by Pak and Moon. Pak hit upon the idea of an American-based foundation to sponsor not only the Little Angels but other Moon projects as well. The foundation should have broad-based appeal, so it could not be identified openly with the Unification Church. Promoting people-to-people relations with Korea and opposing Communism seemed lucrative themes. Americans would contribute money to those causes, especially if recommended by distinguished leaders. Unknowingly, they would be serving Moon, but in the long run they would be rewarded by Moon’s establishing the Kingdom of Heaven on earth.

Thus was born the Korean Cultural and Freedom Foundation (KCFF) in 1964. Unlike some other front groups, the KCFF acknowledged no affiliation with Moon. Bo Hi Pak would pretend his practice of Moon’s religion and his work for KCFF were unrelated. Moon’s founding of the Little Angels would be downplayed so that Pak and the KCFF could get the maximum advantage of appearing independently successful. However, KCFF money would be used to help make the Unification Church strong in America.

The foundation would require more of Pak’s time than was allowed by moonlighting; he could no longer afford to waste his work days at the Embassy. His position there had opened the right doors in Washington, but had outlived its usefulness. The moment had arrived to start working full time for Master. With the church’s government connections in Seoul, he arranged for early retirement from the army. Although now a private citizen, he was able to return to the United States on a diplomatic visa, backed by a letter from the Ministry of National Defense saying he was performing an unspecified special diplomatic mission.

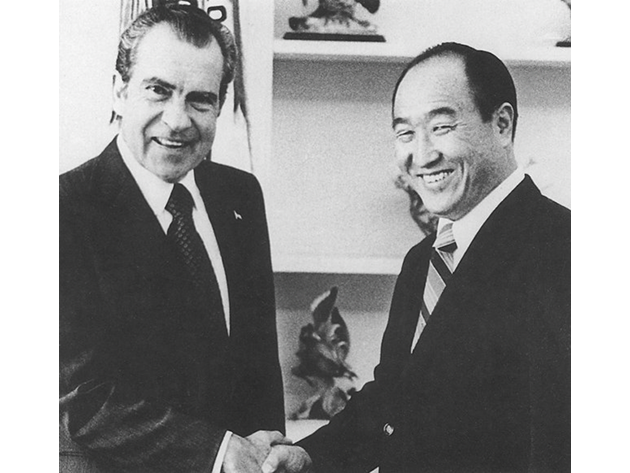

The key to successful fund raising and propaganda was endorsement by influential people. It was essential, therefore, to have the right names in the top positions, although Pak would see to it that he alone ran the foundation. He found a useful figurehead in the person of Yang You-Chan, R.O.K. Ambassador to the United States during the Korean War. Retired and settled in Washington, Yang was known and respected by American government leaders from the fifties and still carried the title of Ambassador-at-Large. He was especially noted for his staunch anti-Communism. Yang agreed to be executive vice-president and persuaded retired Admiral Arleigh Burke to accept the presidency. Bo Hi Pak was vice-president. Burke and Yang gathered an impressive list of names for the KCFF letterhead: former Presidents Truman and Eisenhower as honorary presidents; Kim Jong-Pil as honorary chairman; the directors and advisers included Richard Nixon, George Meany, Perle Mesta, Senator Hugh Scott, Senator Homer Capehart, General Matthew Ridgway, and Congressman Clement Zablocki.

The foundation’s first annual dinner was a formidable event held in the Washington Hilton’s International Ballroom. It featured speeches by Admiral Burke, Korean Ambassador Kim Hyun-Chul, and Assistant Secretary of State William Bundy. Bo Hi Pak was master of ceremonies for the evening’s entertainment: the “Gala National Premiere” of the Little Angels, presented by noted Washington impresario Patrick Hayes.

Moon, like Tongsun Park, is skillful at transforming the illusion of power into real power. Both seized every opportunity to be seen with influential persons and especially to be photographed with them. This technique helped increase their power in Korea by convincing government leaders that they were close to the most important people in America. Likewise, in the United States they exaggerated their actual importance in Korea, which opened more doors to American influence.

During Moon’s first visit to the United States in 1965, Bo Hi Pak arranged through Ambassador Yang for him to meet Dwight Eisenhower at Gettysburg. There was the customary picture-taking. A contingent of Little Angels was brought along to charm the Eisenhowers with a private performance. By receiving Moon, the former President was doing what was expected of him. Moon commented that Eisenhower “paid his bill in full” by opening doors to further recognition by national and international leaders. The pictures from Gettysburg also were put to effective use for recruiting church members.

Admiral Burke resigned in 1965 after about a year as KCFF president. He had originally accepted the position with the understanding that it would be temporary, but in the meantime he had developed misgivings about the organization. Robert Roland had sent him material on the Unification Church describing Pak’s ties with Moon and the hidden purposes of the Little Angels. Also, Bo Hi Pak’s explanations about where the money was going had seemed unconvincing to Burke. Apparently, Burke was never sufficiently alarmed to warn the other prominent persons whose names were being used. Despite the resignation, Pak persisted in using Burke’s name, both on the letterhead and in lobbying for the foundation. Burke, too, had “paid his bill” by acquiring high-level respectability for KCFF.

It was intended that the Little Angels gain prestige for Korea and Moon, and in this they succeeded admirably. Acclaimed by critics for their artistry and charm, they were a hit in the world’s leading concert halls during the sixties and early seventies. They performed before audiences of dignitaries, including an appearance before Queen Elizabeth, and a rare performance at the United Nations, where Secretary General Kurt Waldheim and Governor Nelson Rockefeller were listed as patrons. It was during the United Nations appearance that, for the first time, Moon was publicly acknowledged as the founder. Characteristically, deception was employed for hard-sell effect. In Las Vegas, the Moonie managers conned Liberace, with whom the troupe was performing, into announcing falsely that an invitation had just come from President and Mrs. Ford for a White House performance.

The Korean government took full advantage of the propaganda opportunities afforded by the Little Angels. They were billed as “unofficial ambassadors of good will,” and Korean embassies all over the world eagerly promoted visits by the troupe. KCIA Director Kim Hyung-Wook expedited the issuing of passports (which are hard for Koreans to get and must be re-issued for each trip) for the girls whenever Pak requested them. The government financed overseas tours and donated choice land outside Seoul for a multimillion-dollar school and performing center.

Pak peddled the widely believed story that the girls were orphans, when actually most came from upper-middle-class families who competed to get their daughters in. He discovered the Little Angels could be convenient vehicles for bringing cash for the KCFF into the United States from Japan, where the Moon organization had abundant sources of money. Large amounts could be divided among members of the company before passing through Customs. They could then be divested of the money at Pak’s home, which he maintained as a logistics center whenever the Angels were in the United States. In 1972, a Little Angels traveling group delivered 18 million yen ($58,000).

Moon always regarded the Little Angels as an instrument for exerting influence over social and political institutions. After a successful appearance by them in Japan, he told his followers that “we have laid the foundation to win the embassy personnel stationed in Japan to our side—and through them we can influence their respective nations.” In Korea, where rumors about ties to Moon were becoming a problem because of his growing notoriety, Pak ran a newspaper ad denying that the Little Angels had anything to do with the Unification Church. The troupe’s booking agent, fearful that links with Moon would harm their otherwise excellent reputation, asked for official reassurance. The KCFF board chairman informed him that Moon was merely a friend and supporter of the Little Angels, not unlike millions of others. American Moonies were ordered not to promote them too openly or else “Satan will attack by saying that Reverend Moon is exploiting these children for his own glory.”

For more than ten years the truth about Moon’s scheme was kept from non-Moonies on the KCFF board and from the many thousands of Americans who gave money to the foundation.

The next project for KCFF was Radio of Free Asia (ROFA), launched in 1966. The idea, modeled on Radio Free Europe, was to broadcast anti-Communist programs from South Korea to North Korea, China, and North Vietnam. Moon and Pak gave it a special twist, however. They would conduct mass mailings to Americans asking for money to pay for broadcast facilities in Korea but arrange for free use of transmitters and studios through the KCIA. The money could be pumped into the Unification Church or other Moon activities, as needed. KCFF’s list of American luminaries could be used for promoting ROFA, since the radio was a KCFF project. It was another multipurpose Moonie venture with benefits above and below the surface: promoting anti-Communism, becoming more valuable to the Korean government, gaining greater prominence in the United States, and making money for Moon. Bo Hi Pak was thrilled by it. It was described to prospective contributors as “one of the most daring undertakings against the Communists on the mainland of Asia in the last thirty years.”

Larry Mays was someone Pak thought could be useful without getting in the way. Mays was a mortgage broker in Baltimore when Pak met him in 1965. He was uninterested in Unification Church theology but was drawn to Pak through a shared devotion to anti-Communism. They became good friends. During lunch at the Washington Hilton in June 1966, Mays was surprised to hear Pak suggest to Ambassador Yang that Mays become the first international chairman of Radio of Free Asia. Flattered, Mays accepted immediately. A few weeks later, Pak had him elected to the KCFF Board of Directors.

Bo Hi Pak found Mays a genial, malleable sort. He was enthusiastic and didn’t ask questions about where the money came from or went. He was a good anti-Communist. Though he had no power himself, he had a few moderately influential connections. He could provide a joint Korean-American veneer to the ROFA leadership. Pak could run things easily with Larry Mays around.

The target date for ROFA’s first broadcast was only two months off. The immediate business at hand was for Pak, Yang, and Mays to go to Korea to negotiate with the government for approval to begin operating. Pak expected to use a 500,000-kilo-watt transmitter belonging to the government-owned KBS network, and Mays thought ROFA money would be used to pay for it. Pak told Mays that as international chairman, Mays’s presence in Korea would be important at meetings with President Park, the Prime Minister, and other notables. But before leaving, Pak said, there was one matter that had to be taken care of. He needed approval from the Korean Ambassador to the United States, Kim Hyun-Chul, to go to Korea to complete the ROFA negotiations. Mays asked why. Pak explained that Ambassador Kim had complained that since the Little Angels had come to the United States the previous year without adequate financing, he didn’t believe KCFF had enough money to take on a new project.

Actually, Pak had put KCFF in the red by more than $20,000 with the Little Angels’ visit. Ambassador Kim was worried about the Korean image in Washington if KCFF got into serious financial trouble. He thought the Little Angels project was basically good for Korea, but he was leery about the way Bo Hi Pak handled money. Since Pak had connections at the top of the government in Seoul, Kim’s ability to control him was limited. He did not want to be caught in the middle getting the blame if Pak got into hot water in Washington.

Mays thought ROFA had plenty of money. “Didn’t you tell me we already have more than forty thousand dollars in contributions?” he asked Pak. Mays had never asked to see the financial records. He just assumed everything was in order after reading the brochure.

“Yes, that’s true,” Pak assured him. Mays recalls Pak then saying it would be more convincing to Ambassador Kim if Mays were to tell him ROFA was Mays’s idea and that Mays was paying for the trip with a check made out to Pak, which Pak would show to the Ambassador. Mays agreed to write a $10,000 check for Pak to take to their meeting at the Embassy the next day.

As planned, Mays told the Ambassador it was he who had conceived the idea for ROFA and proposed it to former Ambassador Yang, who in turn informed Pak and obtained approval from the KCFF directors. Ambassador Kim was convinced. The trip to Korea was on.

In Seoul, Pak orchestrated a program to keep Mays busy with trivia while Pak and Yang handled the real work. Mays was assigned a protocol secretary and a chauffeur. He presented an engraved trophy (furnished by Pak) to Prime Minister Chung Il-Kwon. In a call on KCIA Director Kim Hyung-Wook, Mays received a plaque inscribed: “To Lawrence L. Mays—Behind the scenes toward the goal.” He had arrived in Korea with only superficial knowledge of the ROFA project, but even that was of little use at meetings because most of the conversation was in Korean. He did pick up an important piece of information in English though: Pak told the government broadcasting director that $70,000 had been received in contributions from Americans. Back at the Bando Hotel, Mays mentioned the difference between this figure and the $40,000 Pak had told him about in Washington.

“Yes, we received about seventy thousand dollars altogether,” Pak said matter-of-factly.

Mays spoke sternly for the first time. “You will have to account for the difference, then.”

“No need to worry. I had to use the additional money for other expenses.”

“For what?” Mays pressed.

Pak explained that the money had gone to the Unification Church, Mays recalls. The church had been helped by Jhoon Rhee, he said, who had turned over all the profits from the karate schools for Pak to use for upkeep of the church headquarters on S Street in Washington. But more money was needed to feed and house church members.

Mays wondered where Pak drew the line between KCFF and the Unification Church—indeed, whether there was a line at all.

The target date for ROFA’s first broadcast was August 15, the anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japan. The date had been set by Pak many months in advance, and he placed symbolic importance on meeting the deadline. That seemed impossible. August 15 arrived after three days of negotiations with the government and there was no approval yet. Mays went to the President’s Independence Day reception assuming it would take considerably more time to get ROFA going. Much to his surprise, he was greeted by the Minister of Public Information with a big handshake and “Congratulations! President Park has just given word that Radio of Free Asia will go on the air tonight at eleven o’clock.”

Bo Hi Pak really delivers, Mays said to himself. He felt very satisfied that night when he heard the first broadcast, although he had no idea what the announcer was saying. Nor did he know that Pak had delivered via the friendly intervention of Kim Hyung-Wook, the director of the KCIA.

It was not until the morning of August 16 that Mays deviated from Pak’s carefully planned schedule. He called at the American Embassy to talk to Ambassador Winthrop Brown and his staff. They had many questions about ROFA: its affiliation with KCFF, the amount of advance preparation, and how it was that approval was obtained so quickly from the R.O.K. government. Mays, of course, was unable to provide details, but he assured the Embassy the project was well funded with contributions from Americans and that he, as international chairman, would control the content of all programs. Ambassador Brown then came to the point. He had information that the man KCFF had hired to be ROFA’s operations director in Seoul, Kim Kyong-Eup, was working for the KCIA. Mays was astonished and promised to look for a replacement. It was clear Ambassador Brown distrusted Bo Hi Pak and felt the prominent Americans on KCFF’s letterhead were being drawn into something they knew nothing about.

It was important to Mays that the U.S. government look favorably on ROFA. He was hoping that the Voice of America and ROFA could work together in support of anti-Communist goals. He never dreamed the operations director was a KCIA man, but he did remember Ambassador Yang’s saying that the R.O.K. Minister of Public Information had sent him a message in Washington asking KCFF to hire Kim Kyong-Eup.

Bo Hi Pak was at the hotel when Mays returned from the Embassy. Ambassador Yang came immediately at Mays’s request. Mays told them Ambassador Brown was not satisfied with Kim Kyong-Eup and wanted him replaced, not mentioning the KCIA connection. Pak and Yang spent most of the day on the telephone and finally found that Kim Dong-Sung, a former Minister of Public Information, was available for the job. The Embassy told Mays there was no objection. The KCIA connection was still there, however. Kim Dong-Sung previously had been an aide to former KCIA Director Kim Jong-Pil.

The following morning Mays and Pak drove to the outskirts of Seoul to visit the Little Angels school. They were treated to a performance of new dances being prepared for the next American tour. They then went back downtown for lunch with Moon and Kim Jong-Pil, at that time the chairman of President Park’s Democratic Republican party. Lunch was a cheerful affair, with most of the talk in Korean. Moon was happy that ROFA was now on the air, and he presented Mays with a pair of silver chopsticks. Kim Jong-Pil, the silent “Godfather” of Moon’s special relationship with the R.O.K. government, said very little.

Mays returned to Washington alone. Pak and ROFA were not what he had thought. He viewed himself as an American patriot who wanted to do something about Communism; ROFA was to have been a noble undertaking for this cause. But Pak’s overriding loyalty to Moon was diverting ROFA’s money into the Unification Church. The KCIA was involved, too, apparently working with Pak and Moon behind his back and getting ROFA into trouble with the U.S. government. Then there was the $10,000 check. He didn’t mind going along with the little game to get the Korean Ambassador off Pak’s back, but the check was supposed to have been destroyed or returned to him. When he asked about it as they were departing for Seoul, Pak said he would return it when they arrived back in Washington. But Pak’s secretary had telephoned them in Seoul to report that the check had bounced after it was deposited. Pak apologized casually, explaining that his secretary must have deposited the check by mistake. Mays didn’t like being duped.

He was through with Pak, but he still wanted to salvage ROFA. This might be done by incorporating ROFA as an entity separate from KCFF, as should have been done in the first place and as Ambassador Brown had suggested. He gave the whole story to General John Coulter, the president of KCFF. They both resigned from KCFF. On the same day they incorporated ROFA as a separate entity in Baltimore.

The second ROFA was a futile paper exercise. Bo Hi Pak had the organization, the facilities in Korea, and by far the greater determination. He kept ROFA going for nine years. Americans continued to mail in contributions, thinking their money was paying for a privately owned and operated project. Pak was spending at least some of the money on the Unification Church, according to what he had told Mays. And he was using Korean government transmitters free of charge, and leaving the broadcasts under the control of the KCIA.

The Korean Cultural and Freedom Foundation reaped large benefits for Moon. By the end of the sixties his designs on America had shaped up nicely. Bo Hi Pak had been remarkably effective cultivating the American elite. Nixon, Eisenhower, Truman, and others were working for Moon without even knowing it. He could have his picture taken with almost anyone. The Little Angels—secretly his “Divine Principles children”—were winning the hearts of millions. Radio of Free Asia had paid off with money to nourish the young Unification Church in the United States and free air time for anti-Communist broadcasts. Kim Jong-Pil’s early support of the Unification Church had been justified for the Korean government many times over in the successes of the Little Angels, the attention to Korea from KCFF’s influential supporters, and the church’s anti-Communism and loyalty to the Park regime. There was a mutually advantageous relationship wherein the Moon organization and the Korean government served each other. There was little mutual trust though; each side was suspicious of the other’s designs on it. But both made maximum use of the indulgence of Americans. Moon and the Korean government had done well indeed by Bo Hi Pak’s diligent labor.

Until he and Korea take over the world, Moon says, it is God’s will that America have custody of all the world’s land that is not Communist. As an archangel, it had been vested with stewardship over all of God’s property. But America had failed. The first failure was at the end of World War II when the Communists were allowed to join the United Nations. The decline continued: not enough was done to fight Communism, especially in Korea, so America was punished with the death of President Kennedy. Drug problems, free sex, crime in the streets, and family disunity were all grim evidence of Satan’s undermining power. Among American leaders, Moon saw not a single true patriot, but only small men obsessed with authority. Moon resolved that he alone would train future leaders. Into the moral void the Lord of the Second Advent would go so that “someday they will realize that I am truly the most noble and precious VIP that ever came to America.”

In 1969, Moon decided it was time to get his rank and file in America busy combating Communism. He had been waging extensive anti-Communist campaigns in Korea and Japan under the aegis of his International Federation for the Extermination of Communism, with political and financial support from Ryoichi Sasakawa and Yoshio Kodama and other powerful Japanese right-wing figures. He organized the Freedom Leadership Foundation (FLF), the American branch of his international federation. Its president, Allen Tate Wood, mobilized Moonie groups throughout the country to lobby for the hawk position in Vietnam and to try to diffuse the peace movement.

Wood and eight other American Moonie leaders attended the annual conference of the World Anti-Communist League in Kyoto, Japan, in September 1970. The conference was the biggest ever held by the world league, largely because the sponsoring organization that year was a Moon group, Shokyo Rengo, the Japanese branch of his international anti-Communist federation. Master ordered the Japanese Moonies to prepare for the event with a massive fund raising drive, which reportedly yielded $1.4 million brought in by selling flowers in the streets. Through KCFF, the Moon organization was able to engage Senator Strom Thurmond as guest speaker.

Allen Tate Wood then proceeded to Korea to meet Master. The fall of 1970 was an opportune time for briefing the head of the Moonies’ American political organ. The Korean government was just then making plans for an influence campaign in the United States. Wood had several private audiences with Moon. It was clear that Master was preparing for a major expansion into the political field in the United States with a new sense of urgency. According to Tate, Moon said:

“FLF will probably win first the academic community. Once we can control two or three universities, then we will be on the way to controlling the reins of the certification for the major professions in the United States. That is what we want to do because universities are the crucible in which young Americans are formed. So if we can get hold of those, then we can move out into politics, into economics, and so on.”

But above all, Master stressed, “We must guarantee unlimited military assistance to South Korea and prevent further withdrawal of American forces.” Those were exactly the two objectives of the Korean government’s campaign to influence United States policy. It had been approved in secret by President Park only a few weeks before, and the Moon organization had been assigned a key role.

NOTES Abbreviations of Frequently Cited Sources

KI Report: Investigation of Korean-American Relations, Report of the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, Oct. 31, 1978, 447 pages.

SIO-I: Activities of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency in the United States, Part I, Hearings before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, March 17 and 25, 1976, 110 pages.

SIO-II: Activities of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency in the United States, Part II, Hearings before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, June 22, Sept. 27 and 30, 1976, 87 pages.

KI Part 1: Investigation of Korean-American Relations, Part 1, Hearings before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, June 22, 1977, 75 pages.

KI Part 3: Investigation of Korean-American Relations, Part 3, Hearings before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, Nov. 29 and 30, 1977, 209 pages.

KI Part 4: Investigation of Korean-American Relations, Part 4, Hearings before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, March 15, 16, 21, 22, April 11, 20, and June 20, 1978, 721 pages.

KI Part 5: Investigation of Korean-American Relations, Part 5, Hearings before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, June 1, 6, and 7, 1978, 227 pages.

KI Part 7: Investigation of Korean-American Relations, Part 7, Hearings before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, June 22, 1977, July 20, 1978, Aug. 15, 1978, 92 pages.

KI Appendix: Investigation of Korean-American Relations, Appendixes to the Report of the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, Oct. 31, 1978, 2 volumes, 1,523 pages.

House Ethics Report: Korean Influence Investigation, Report of the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, Dec. 1978, 218 pages.

House Ethics Part 1: Korean Influence Investigation, Part 1, Hearings before the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, Oct. 19, 20, and 21, 1977, 581 pages.

House Ethics Part 2: Korean Influence Investigation, Part 2, Hearings before the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, April 3, 4, 5, 10, and 11, 1978, 1,157 pages.

Senate Ethics Report: Korean Influence Inquiry, Report of the Select Committee on Ethics, U.S. Senate, Washington, Nov. 1978.

Senate Ethics Part 1: Korean Influence Inquiry, Executive Session Hearings before the Select Committee on Ethics, U.S. Senate, Washington, March 14, 15, 16, 17, 22, 23, and April 10, 11, 27, 1978, 857 pages.

Senate Ethics Part 2: Korean Influence Inquiry, Hearings before the Select Committee on Ethics, U.S. Senate, Washington, May 1978, 1,273 pages.

NOTES for Chapter 2 THE LORD OF THE SECOND ADVENT

Commentary on Moon’s theology was derived from The Divine Principle (a publication of the Unification Church), Moon’s speeches to his followers published for internal use by the cult under the title of Master Speaks, and interviews with former Moonies, including some who were instructors in the Divine Principle.

31 “You are the son I have been seeking”: Master Speaks, Feb. 23, 1977 (KI Appendix C-227).

32 “The reason why Jesus died was because he couldn’t have a bride”: Master Speaks, Dec. 27, 1971 (KI Appendix C-207).

35 “Rumors reached the American Embassy”: Interview with officer of the U.S. Embassy, Seoul, during the late fifties.