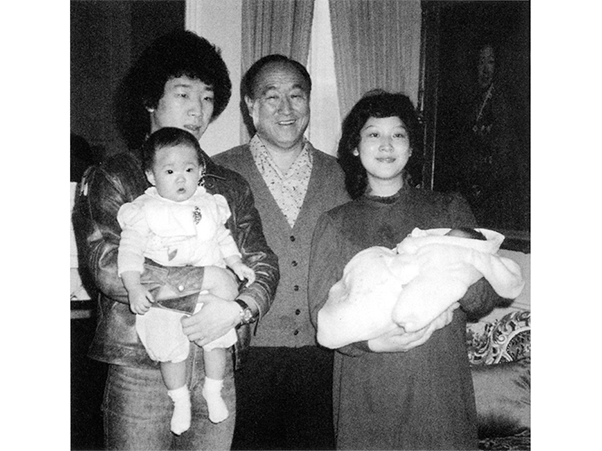

▲ One of my daughters greets Sun Myung Moon on his return from a trip overseas. The men applauding in the background are church members and leaders.

In The Shadow Of The Moons: My Life In The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Family.

by Nansook Hong 1998

Chapter 3

page 51

The Little Angels Art School is one of the finest schools for the creative and performing arts in South Korea. It is owned and operated by the Unification Church, but there are no overt signs of the primary and secondary school’s connection to the Reverend Sun Myung Moon. Most of the teachers and the majority of students are not Moonies. Religion is not part of the curriculum.

Like so many institutions run by the Reverend Moon around the world, the Little Angels school downplays its relationship with a religious sect that is still deeply distrusted, even in its founder’s homeland.

I entered Little Angels in the sixth grade, joining my older brother, Jin, on the sprawling campus, which then housed classes for students in grades seven through twelve. It has since expanded to include the elementary grades.

The school is on the outskirts of Seoul, about fifteen miles from our home. Jin and I would leave our house at 7:00 a.m. to catch the no. 522 city bus. The buses were always crowded with adults on their way to work and students laden with heavy schoolbags. Four or five buses would routinely pass us by, too packed to pick up even two extra passengers. We would pray for the chance to court suffocation if only a bus would stop.

Arriving late was not tolerated at Little Angels. A tardy student would be forced to sit on a concrete bench outside the principal’s office with her arms raised above her head for thirty minutes. She would then be required to write a letter of apology to her teacher and classmates for the disruption her late arrival had caused.

On the way to and from the bus stop, Jin insisted I walk several paces behind him. Being seen with one’s little sister is no less a humiliation for an adolescent boy in Seoul than in the rest of the world. I willingly obliged. I treated my brother with a formal respect that my nonchurch friends found both curious and amusing. When I spoke to him, I even used the form of address Korean children reserve for adults.

In many ways, my relationship with my brother replicated the one between my parents. Korea’s is a rigid, patriarchal culture. My father was a gentle man but he was no egalitarian. He was the undisputed head of our household. His position was reinforced by the teachings of the Unification Church. A marriage is one of mutual respect, but the wife is in the “object” position to her husband just as mankind is in the “object” position to God. I never questioned the balance of power between my mother and father, and I unconsciously modeled my behavior toward my brother on their example.

By the time I was in middle school, the Reverend Moon and his family had moved to the United States. He was directed by God to move to America in 1971, he told his followers, because the United States was on the verge of a moral collapse similar to that which destroyed Rome in the first century.

He went to America to save it from itself. He went preaching his own brand of rabid anti-Communism and moral fundamentalism. He conducted rallies across the United States and found a following among alienated youth caught in the American “generation gap,” young people out of step with both their parents and their peers. Their entree into the Unification Church was often through CARP — the Collegiate Association for the Research of Principles.

CARP was established in the United States in 1973, at the height of protests against American expansion of the war in Vietnam into Cambodia and Laos. The Reverend Moon’s dire warnings of the threat of Communism fell largely on deaf ears among American students incensed by their own country’s imperialism. CARP recruiters targeted the idealistic and the lonely on college campuses. Students too conservative or apolitical to find common cause with the antiwar movement often found a mission in CARP.

Typical of the membership were the dozens of fresh-faced, neatly dressed young people who staged a day of prayer and fasting on the sidewalk outside the White House in support of President Richard M. Nixon during the Watergate hearings. They held signs that said Forgive, Love, Unite. They were there, on the Washington Mall, on the fringes of antiwar demonstrations, extolling the value of patriotism and the courage of President Nixon in the face of his godless critics.

When CARP members in the United States were not offering encouragement to an embattled president, they were selling flowers on campus, on street corners, in airports, at shopping centers, to raise money for the Reverend Sun Myung Moon and his divine mission.

“The victory of the Allied side in World War II was not an end in itself. From the providential point of view, it had the purpose of preparing America and the world for the Second Coming of the Messiah,” Sun Myung Moon has written. “What has happened? The United States did not grasp such a vision. For 40 years, this country has been drifting down the path of self-indulgence, fun and destruction. Drugs have infiltrated the whole country; young people have been corrupted and turn more and more toward delinquency; free sex has become a way of life. But this has not been limited to the United States. As the leader of the free world, the United States has infected the world with its ills. Unless something stops this trend, this nation and the whole world are destined to collapse.”

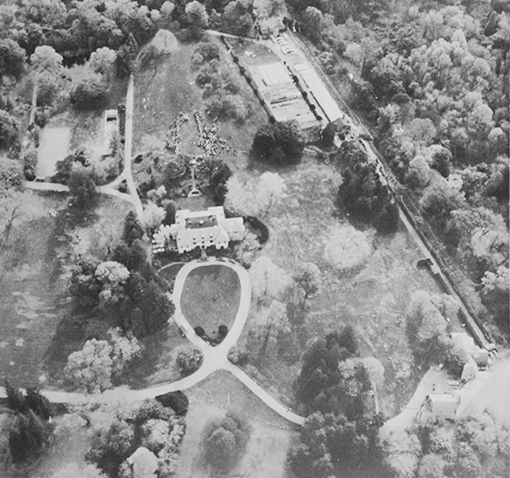

The man who could prevent the Apocalypse, of course, was Sun Myung Moon. To that end, the Reverend Moon himself settled with his growing family into a mansion in the quaint village of Tarrytown, in the Hudson River valley of New York. In 1972 he purchased twenty-two acres in Westchester County for $850,000. The Belvedere Estate was one of the area’s architectural gems. The stucco mansion was built in 1920 with sixteen bedrooms, six large public rooms for living and dining, ten full bathrooms, a commercial-sized kitchen, and a full basement. The mansion looked out over rolling lawns, ancient trees, and an artificial one-acre pond, complete with wooden bridge and waterfall. There was a swimming pool and tennis courts and breathtaking views of the Hudson River from the quarry-tiled second-floor sundeck.

▲ Sun Myung Moon on the rock at Belvedere

Five other buildings stood on the property, including a carriage house that was only slightly smaller than the mansion, with ten bedrooms and three full baths and ten public rooms. There was a five-bedroom wood-frame cottage built in 1735, a gardener’s cottage, an artist studio, and a recreation building, plus a four-thousand-square-foot garage and three large greenhouses.

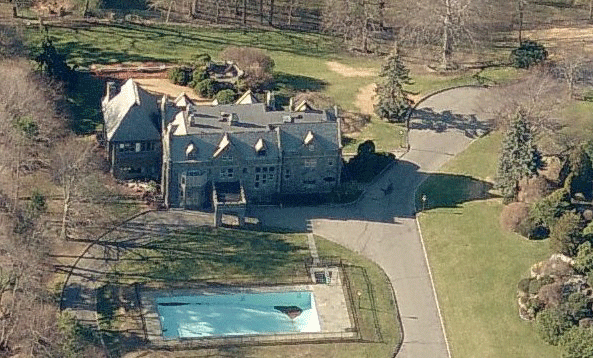

A year later the Reverend Moon purchased a second, eighteen-acre estate not far from Belvedere for $566,150. The centerpiece of the property was a three-story brick mansion with twelve bedrooms, seven bathrooms, a living room, dining room, den, kitchen, and enormous tiled solarium on the west side of the house. The Reverend Moon christened the place East Garden when he and his family took up residence. The Moons retained a private suite of rooms in Belvedere but used that estate primarily to host guests and church functions.

Small buildings dotted the rustic East Garden estate overlooking the Hudson River. A security booth guarded the entrance on Sunnyside Lane, and nearby was a gatehouse with two bedrooms, a bathroom, a living room, and a kitchen, plus a small basement. Just up the hill from the mansion was a lovely stone house with two bedrooms, a bathroom, living room, dining room, den, and kitchen. It was known as Cottage House.

New York was the base of the Reverend Moon’s operations, but he still made frequent visits to Korea. When he did, he or one of his top aides would sometimes visit the Little Angels Art School. It was always an occasion for rejoicing as much for the interruption of regular class time as for the chance to see the man some of us considered the new Messiah and all of us knew to be the school’s wealthy benefactor.

Korean schools are much like those in Japan and throughout the Pacific Rim. The emphasis is on rote memorization and repetitive drills. By the end of elementary school, I could do advanced mathematics but I could not think critically. It was not a skill that was either taught or valued. Children’s minds were considered empty vessels to be filled with knowledge. We were clay to be molded, sculptures to be shaped. This was as true of our moral as of our intellectual development. The educational system, no different at Little Angels school than elsewhere in Korea, stressed deference to authority. It prized consensus and conformity, obedience and acceptance. It prepared me perfectly for life in an authoritarian religion that did not tolerate dissent.

Because I was a disciplined child, academics and music came easily to me. I was a good student by Korean standards. I studied piano with a dutifulness but a lack of fire that I knew pained my mother’s heart. I had not inherited her passion for the instrument. I won school piano competitions in the third and sixth grades, but the concert stage was my mother’s dream, not mine.

In November 1980 we were pleased to learn that the daily school routine would be broken by a visit from Bo Hi Pak, one of the Reverend Moon’s close advisers, to Little Angels. By then the Reverend Moon had become a darling of conservative Republicans in the United States. He had mastered the art of the photo opportunity, having his picture taken with as many prominent world leaders as he could engineer. Those photographs were presented to us as concrete evidence of Father’s growing influence in the world.

That day, at Little Angels, Bo Hi Pak was extolling Father’s influence on the outcome of the recent American election. A photograph of President Ronald Reagan displaying a front page of the Moon-owned newspaper, the News World, proclaiming his landslide victory flashed overhead as Bo Hi Pak spoke. I can’t say I paid much attention to the content of his speech. I was thirteen years old, an eighth-grade student. International politics did not interest me. What I knew of America had less to do with politics than with fashion and music, movies and pop culture.

▲ News World front cover

November 1980: “Reagan Landslide

– Will win by more than 350 electoral votes and carry New York as well.”

My attention was diverted during his speech by the chattering of my best friend, Hae Sam Hyung, in the next seat. Hae Sam’s parents had been part of a group of seventy-two couples who received the marriage Blessing soon after my own parents. “You don’t know it yet, but you are going to be matched to Hyo Jin Nim,” she whispered while Bo Hi Pak droned on. I stifled a laugh. “That’s ridiculous,” I said. How would she know such a thing? There were always rumors about who would be chosen to marry the True Children, but those decisions would be made by the Reverend Moon, not by girls giggling in the school auditorium.

Two years later the idea still seemed ridiculous. I had never said more than a few words to Hyo Jin Moon in my life. There were many Blessed Children his own age who would make more suitable marriage partners for a nineteen-year-old True Child than a fifteen-year-old girl like me. I did not know Hyo Jin well but I had heard enough to know he was the black sheep of the Moon family. He was in elementary school when the Moons moved to America. He had been a diligent, if reluctant, student in Korea. Peter Kim, the Reverend Moon’s personal assistant, was assigned to tutor the young heir apparent. Hyo Jin vowed that when he went to America, he would have more freedom than he had known in Seoul.

The move to the United States was not an easy transition for him. Life was even more isolated in the Moon compound in Tarrytown than it had been in Seoul. At home the Moon children were left to the care of church elders and baby-sitters. At school they were the ultimate outsiders.

They were sent to the private Hackley School, where their identities as Moonies subjected them to teasing or outright scorn. Hyo Jin was expelled from Hackley in middle school for bringing a BB gun to school and shooting at several classmates. Hyo Jin claimed the headmaster thought him both honest and amusing because he admitted that his reason for doing it was nothing more complicated than that it was fun. He was expelled nonetheless. He had been terrified to face his father after his expulsion. Had the Reverend Moon punished his son decisively back then, he might have saved us all a lot of grief. Instead the Reverend Moon treated Hyo Jin as if he were the victim of religious persecution. It was part of a lifetime pattern of evading his responsibility for Hyo Jin Moon.

The Reverend and Mrs. Moon were absentee parents, promoting the church around the world and ignoring their own children at home. Hyo Jin was an especially difficult challenge. As their oldest son, he would be expected to inherit Father’s place as head of the church. But a long-haired rock guitarist with a chip on his shoulder was not what the Reverend Moon had in mind for a successor.

After Hyo Jin was expelled from Hackley, the Reverend Moon sent him to live with Bo Hi Pak, one of his original disciples, in McLean, a wealthy Virginia suburb outside of Washington, D.C. It was the Reverend Moon’s theory that his followers were responsible for rearing the Messiah’s children. The Reverend Moon, after all, was responsible for the care of the world. It was an odd theory for a man who claimed to be the model father of the ideal family, and no one felt the dichotomy more than Hyo Jin Moon.

Hyo Jin’s behavior only deteriorated in Washington. In a large public school, there were fistfights and worse. It was in Washington that he was first introduced to illegal drugs. “Going to Washington was a great excitement for me, to leave East Garden,” Hyo Jin told church members in a speech in 1988.

Father told me not to associate with outside kids but I wanted to associate with outside people. I felt this was a chance for me to seek friends. I didn’t think, didn’t care, about what Father wanted. I wanted my own friends. After I went to Washington, I started getting into drugs. I didn’t want to be pressured by bullies anymore. When you’re in high school, fists work. I started taking martial arts. I didn’t want to take anything from anyone. In school, they go around in packs. But kids who had control were the strongest. When they saw me, they saw “gooks,” so I had a lot of fights. The more I fought, the more I won. Then kids wanted to become friends. My name was notorious.

A frustrated Reverend Moon sent Hyo Jin back to Korea for high school, hoping that the supervision of church elders in his own culture would straighten him out. It did not work out that way. Hyo Jin was quite a sight in the corridors of Little Angels, with his long, dirty hair and his tight blue jeans. He started a rock ’n’ roll band and he cultivated a reputation for defiance.

It was hard enough to belong to a mistrusted religious sect as an adolescent. Hyo Jin’s appearance and behavior made it more difficult for the rest of us. We were embarrassed by him in front of nonmembers. Our own musical tastes ran more to the classical. To compound matters, he was openly contemptuous of Father’s strict code of conduct. Everyone in school knew Hyo Jin smoked cigarettes, had girlfriends, and drank alcohol. Some whispered that he used illegal drugs. He never actually finished his course of study at Little Angels; years later the school simply mailed him a diploma.

There was enormous competition among the thirty-six Blessed Couples, the original members of the church, to have one of their daughters matched to Hyo Jin Moon. One’s standing in the church was directly related to one’s proximity to Sun Myung Moon. To be an in-law was to be as close as a member could get. Mr. and Mrs. Young-Whi Kim, for example, expected their eldest daughter, Un-Sook Kim, to be matched to Hyo Jin because of their status as one of the original Three Couples. Young-Whi Kim was then the president of the Unification Church in Korea. The irony was that even those couples who wanted their daughters to marry Hyo Jin discouraged their children, of both genders, from associating with him because of his taste for drugs and sex and rock ’n’ roll.

As for Hyo Jin, he wanted nothing to do with being matched for “spiritual” reasons. “When I went to Korea, I started going with many girls,” he confessed in his 1988 speech to members.

I really loved one in particular and wanted to marry her. Her parents liked the idea; they thought Father had a lot of money. They encouraged both of us, invited me to their home. They were nice to me. We became very close, almost lived together. I had sex with her. I wanted to do everything in my power to stay with her. I wanted to be matched with her or nobody else. After school, I would sleep over at her house and she at my house, all through high school.

I drank a bottle of whiskey a day. If I didn’t have money, I would buy corn whiskey, cheap and potent. I had to be drunk all the time. … I touched bottom. I was listening to my heart cry. I started suffocating. I wanted to kill myself. How could I face Father. I thought the best way was to disappear, then I would have no burden. Many times I sat with a gun pointed to my head, practiced what it would be like. I only cared about my physical body. I was worse than other kids. I was so physical and selfish. I didn’t care how I affected other people. That’s how I grew up.

What did I know of boys, never mind bad boys like Hyo Jin Moon? Girls and boys attend separate schools in Korea. At Little Angels, an arts school that attracted an overwhelmingly female student body, there were a few boys, but they did not mix much with the girls. Most boys were members of the Unification Church and, as such, were not allowed to date.

My only encounter with a boy as a teenager had left me with the overriding impression that the opposite sex was an annoyance to be avoided. A boy my age would hang round outside our church on Sundays when I was thirteen, waiting for me to emerge. He was not a member of the Unification Church but lived in the neighborhood. He must have spotted me going to and from the bus stop. Every week he would try to strike up a conversation and every week I would ignore him. I was delighted when we moved to a new church building in another neighborhood. I would be rid of him. But there he was, that first Sunday, waiting for me outside the new church. I never knew his name; eventually he gave up his pursuit.

Among my friends at Little Angels, there was the usual innocent preteen talk about which boys ranked among the cutest. I would just listen. Having begun school so early, I was a year younger than most of my classmates. I was smaller physically, too, still a pretty little girl when my friends were flowering into graceful young women.

We knew we’d all be matched someday by the Reverend Moon to the men we would marry. We assumed that eventuality was years away, after we had completed our studies at the university and begun our lives as adults. The median age for a woman to marry in Korea is twenty-five. When the time came, I knew that I would accept the Reverend Moon’s choice for me. My parents expected it. I would obey. I gave the prospect of marriage little thought because it would not happen for years and I would have little to say about it when it did.

In my deference to my elders in the matter of marriage, I was not so different from other young women in my culture. Arranged marriages are still commonplace in Korea, where they have been the traditional means of maintaining or elevating a family’s social status for centuries. Many young people taken with Western influences do marry for love, but most Koreans remain skeptical that romance provides a solid foundation for family life. Even lovers who choose one another as marriage partners often confirm their decision by visiting a fortune-teller.

It would be hard to overstate my naïveté as a fifteen-year-old girl. My mother had explained menstruation to me when I was ten. It was the only time that she and I even came close to discussing sex. The atmosphere in the room that day was so heavy, her discomfort so pronounced, we might have been discussing a fatal disease. I remember squirming as I sat on the floor, wanting to relieve her embarrassment more than I wanted to learn any womanly secrets she had to impart.

The truth is, I had little curiosity about the whispers and giggles I heard in the school corridors between boys and girls. I made no effort to decipher the punch lines of jokes I did not understand. Once, on the bus, I stood next to a teacher with a reputation for bothering girls at school. He grabbed my hand and stared at me throughout the ride. I tried to pull my hand away but he was too strong. My fingers turned red, then white, in his tight grasp. I thought it was odd, but it never occurred to me there might be some sexual threat in his advances.

During that assembly at school, I had laughed about my friend’s prediction of a marriage between me and Hyo Jin Moon, though I did tell my mother when I returned home. She looked surprised, but we never spoke of it again. One day we would be distracted not by rumor but by a real match in the Hong household.

When I first entered Little Angels Art School, older girls would whisper when I walked past, “That’s Jin’s little sister,” and pride would make my chest swell. I basked in his reflected glory. Jin was the most popular boy in school. He was handsome, smart, the class president. It was an honor to be his sister.

At school more than one girl wrote him silly love notes. He blushed at their attention, but he was a good boy. He took the moral code of the church seriously. We were forbidden to have anything other than a sisterly or brotherly relationship with members of the opposite sex. We were not allowed to date. We were to keep ourselves pure until Father decided it was time for us to marry.

When Jin was seventeen and I barely fifteen, I could sense there was something about to happen in our house. The whole atmosphere was charged. There was an undercurrent of tension and excitement, although my parents said nothing to us children. The Moons were living in the United States at the time, but rumors were rife that they were looking among the Blessed Children in Korea for a groom for their oldest child, Je Jin. Everyone expected the groom to be chosen from among the sons of the earliest disciples, Young-Whi Kim or Hyo Won Eu. Their sons, Jin-Kun Kim and Jin-Seung Eu, were friends of my older brother.

One day, after school, I was surprised to see both of my parents at home, outfitted in their best clothes. I could hear Jin, dressing in his room. He emerged in a new suit, with his hair slicked back like a Korean businessman’s. My brothers and sisters and I gasped. He looked so grown up. My parents offered no explanation and, characteristically, we did not ask. It was not until they returned from their mysterious errand with Jin hours later that they told the six of us that our brother had been matched to Je Jin Moon. He was to be married to the daughter of the Messiah. He was to become a member of the True Family of God.

I was so proud. Jin was special and I would be special, too, because Jin was my brother. My pride gave way to sadness when I thought about his actually leaving our family. He was so young, and he was so much a part of my life. Ours was not so religious a household that we did not sometimes bend the rigid rules of the church. Gambling was forbidden by the Reverend Moon as a corrupting influence, but my brothers and sisters and I often played a Korean card game called Wha Tu. The losers sometimes would buy the winner a lunch of black Chinese noodles, delivered to our front door straight from the restaurant by a boy on a bicycle. Would that end now, without Jin?

With Jin gone, who would help me with the art classes in which I struggled so? My sadness paled, though, next to Choong Sook’s, who faced the prospect of me as the eldest sibling in the Hong family. I had not learned from the example of my brother, who exerted authority among us by the goodness of his character. I took the more direct approach to power. I am ashamed to say that I treated Choong Sook, who was two years younger than I, like my personal servant. My grandmother even called me Choon Hyang after the lady in a famous Korean love story and my sister Hyang Dan, after the lady’s maid.

We were stunned to learn that the wedding of Je Jin and Jin would be held the next day. We had all been taught the significance of the marriage Blessing, its central role in our spiritual lives and the need to approach that moment with due deliberation. Je Jin and Jin could not possibly have had time to do that. It was as though the Reverend Moon were marrying off his daughter between stops on one of his world tours.

Marriage is at the center of Unification doctrine. The Reverend Moon teaches that, because Jesus was crucified before he could marry and sire sinless children, the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth had not been opened to mankind. It is the Reverend Moon’s role as Lord of the Second Advent to complete the work Jesus left undone. The Reverend Moon’s marriage to Hak Ja Han in 1960 began a new era, one that the Unification Church calls the Completed Testament Era. This perfect couple, the True Parents, produced the first True Family by having children born free of original sin. The rest of humankind can become part of this sinless legacy only by receiving the marriage Blessing from the Unification Church.

The Reverend and Mrs. Moon would complete Jesus’ mission to restore humanity by reenacting the role of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, this time without sin. Since the Unification Church teaches that the Fall was an act of sexual misconduct, the Reverend Moon will restore humanity through a “principled,” monogamous marriage. Other couples could be freed from the satanic blood lineage of Adam and Eve — original sin — only by receiving the Blessing and becoming one with the True Family.

Before and after receiving the Blessing, the church requires a couple to participate in several complex rituals, most of which were waived in the case of Je Jin Moon and Jin Hong. The Reverend Moon teaches that three years should elapse between the initial Matching Ceremony and the actual consummation of the marriage in what is called the Three Day Ceremony. In this case, there was no Matching Ceremony, no Holy Wine Ceremony, no Indemnity Ceremony, no Three Day Ceremony, even though the Reverend Moon teaches that each very specific ritual has profound theological meaning.

Theoretically, to become engaged in the Unification Church, one must have been a member for three years, one must have recruited three new members, and one must have made the required financial contribution to the Indemnity Fund. This payment symbolizes Unification teaching that all of humanity shares in the debt owed for the betrayal of Jesus and that we must all pay for this collective sin. In the Matching Ceremony, a couple is called before the Reverend and Mrs. Moon, who explain the significance of the Blessing and ask them to adjourn to a separate room to decide whether to accept the match. As the church grew, the Blessing Committee was formed to rule on matches, but in the early days and in the case of his family, the Reverend Moon made the matches himself.

The Holy Wine Ceremony is usually held the same day as the Matching Ceremony. Facing the man, the woman drinks half a cup of blessed wine and then passes the cup to the man. The woman drinks first to symbolize Eve, the first to sin and now the first to be restored to grace. The few drops left in the cup are sprinkled on a Holy Handkerchief to be used after the Blessing at the Three Day Ceremony. After a couple receives the Blessing, there is a [usually not] private Indemnity Ceremony in which the husband and wife each ritually and symbolically “beat” Satan out of the other with sticks.

▲ The Indemnity Stick Ceremony. Each spouse has to strike the other as hard as they can three times. In a very few cases injuries have been incurred which required hospital care.

The Three Day Ceremony is the consummation of the marriage. In most situations the couple is not to have sex for the first three years of their married life. When they do, they must follow a detailed pattern of sex acts prescribed by the Reverend Moon. On the morning of the third day, the couple joins together in prayer. They then bathe and wipe their bodies with the Holy Handkerchief, which has been dipped first in wine and then in cold water. The woman takes the superior position for the first two nights, symbolizing a restored Eve bringing grace first to Satan and then to the fallen Adam. On the third night, the man assumes the superior position, symbolizing the restored Adam and Eve fulfilling the mission God had intended for them at the dawn of creation.

This was the first wedding of a True Child of the Reverend and Mrs. Moon. The absence of many of the Blessing-related rituals was something of a shock. The whole proceeding had the air of a shotgun wedding. What was the rush? I wondered. Why was church doctrine being set aside to marry Je Jin and Jin almost literally overnight? Much later I would learn that the rules did not apply to the Moon family. All had sex immediately after the Blessing, if they had not already had sex before.

My siblings and I were not thinking about that as we sat at the back of the church. Our parents were up front with the Moons and the bride and groom. We could barely see. We all missed a day of school to attend the ceremony. Je Jin was beautiful in a white wedding gown and my brother was more handsome than ever, like the plastic groom on top of a wedding cake. We had to strain to hear them exchange their vows.

Do you, as mature men and women, who are to consummate the ideal of the creation of God, pledge to become an eternal husband and wife?

Do you pledge that you shall become a true husband and wife, and raise your children to live up to the will of God, and educate them to become responsible leaders in front of your family, all humankind, and Almighty God?

Do you pledge that, centering on True Parents, you shall inherit the tradition of family unity, and pass this proud tradition down to the future generations of your family and all humankind?

Do you pledge that, centering upon the ideal of creation, you will inherit the will of God and the True Parents, establish God’s traditions of the love of children, brother and sister, husband and wife and parents [the Four Great Realms of the Heart] and the love of grandparents, parents and children [the Three Great Kingships] and love the people of the world as God and True Parents do, and ultimately consummate the ideal family which is the building block of the Kingdom of God on earth and in Heaven?

As they made their vows, I saw Hyo Jin Moon across the room, his long hair spilling over the collar of his dark suit. He was taking photographs of the ceremony but he looked sour and angry. I was mystified. Why would anyone look so unhappy at a wedding? It is only in retrospect that I recognize the familiar pattern: I suspect Hyo Jin was sulking because he was not the center of attention.

After the wedding a dinner reception was held in a large ballroom in the Palace Hotel. Our parents were there with all of the Moons, but we, Jin’s brothers and sisters, were not invited to attend. One of my uncles took the six of us to dinner in a hotel restaurant, but we were heartbroken to be excluded from our brother’s wedding celebration. This was a Moon affair; the Hongs were clearly secondary players.

Soon after the wedding, the Moons and Je Jin flew back to America. Je Jin was a student at Smith, the prestigious women’s college in Massachusetts. Jin moved into the Reverend Moon’s house in Seoul with Hyo Jin and a large household staff. He still had a year of high school to complete, and it was not easy to obtain a visa to travel to the United States.

Living with Hyo Jin was difficult for my brother. Hyo Jin had been raised as a prince and he acted like one, leaving his clothes on the floor to be picked up by the sisters and ordering the household staff around as if they were his personal slaves. He brought his girlfriends home to the house to have sex. He filled the place with cigarette smoke. Jin was in an impossible position. He disapproved of Hyo Jin’s behavior but he could not criticize the son of the Messiah. Hyo Jin was a True Child; Jin had merely married one.

My own life resumed its routine after my brother’s marriage. I would see him at Little Angels, but we shared little more than passing conversation. He studied all the time. Regular school hours end at 3:00 p.m. but older students often stay until 9:00 p.m. to prepare for university entrance exams. Besides, Jin was on another, higher plane now. He was no longer my brother but a member of the True Family. I missed him terribly.

When I thought about my own future, and I rarely did, I envisioned many more years of study. I never missed a day of school. I was becoming more diligent at the piano. Maybe I would fulfill my mother’s dream and become a pianist after all. Maybe I would marry another pianist and we could play concerts together around the world. Hadn’t a fortune-teller once told my mother that I would be very famous one day, married to an important man?

Such thoughts were all in the realm of girlish fantasy. I followed the rigid code of the Unification Church. I was aghast in class one afternoon to see my seat-mate applying eye makeup. She was not a member of the church. She had a date after school, she said. I was at once fascinated and horrified.

Six months after the Blessing of Je Jin and Jin, in November 1981, the Little Angels Art School staged a production of traditional Korean music and dance to celebrate the opening of a new theater. The school had expanded steadily since it was founded by the Reverend Moon in 1974. The adjoining performance arts center was home to the Little Angels folk ballet that the Reverend Moon had established in 1965. The Little Angels, a troupe of seven- to fifteen-year-old girls, have performed around the world for heads of state and royalty in Japan and Great Britain.

I had no such performing talent. For the theater dedication, I was given a small role in the chorus. I was a nervous wreck as I waited backstage with the other girls, my hair pulled back into a tight single braid, my beautiful costume no disguise, I knew, for my terrible voice.

The conductor was lining us up to go onstage when I heard my name called. The principal was suddenly at my side. “Your mother has sent a car for you,” she said. “You must go and change.”

I returned to the dressing room to replace my costume with my school uniform. I stepped into the navy blue plaid skirt, buttoned my white blouse, and slipped on my blue blazer. I put on the gray wool coat with the black fur collar that was part of our winter uniform, grabbed my red hat and red book bag, and hurried to the waiting sedan. I got into the rear seat of the car with no idea where I was being taken. It speaks volumes about my level of obedience that I did not ask.

I had never been to the Reverend Moon’s private residence. It was an enormous house with an elaborate front gate that led to a large courtyard. A sister led me to an ornate dining room. My mother was already there. Three chairs were lined up on either side of the rectangular dining table. The Reverend Moon sat at the head; Mrs. Moon sat to his right. Beside her sat a woman I did not recognize. Next to her was Mrs. Young-Whi Kim. My mother was seated opposite Mrs. Moon. My mother smiled and gestured for me to sit beside her. I kept my eyes downcast, focusing on the patterns of light and shadow cast by the large crystal chandelier on the white linen tablecloth.

My head remained bowed as the kitchen sisters served course after course of the dinner meal. I was too scared to eat the rice or soup or kimchi or seafood or meat. I moved the food around my plate and prayed no one would take notice of me.

It struck me that Mrs. Moon seemed to be in very good spirits. There was a lot of laughter, but I did not focus on the conversation until I suddenly realized they were talking about me. The woman at the table whom I had not recognized was staring at me. She was commenting on my forehead and the shape of my head. She was delighted that my hair had been pulled back for the performance at school. It gave her the opportunity to examine my ears more closely. I could feel my face flush as she cataloged the positive characteristics of my ears: earlobes that were long and fat, a shape that was well proportioned. All this meant longevity and good fortune.

I felt panic as my mother rose to clear her plate as the dinner gathering was breaking up. I followed her through the swinging doors into the kitchen, where the sisters laughed and smiled, obviously pleased by something more than my ears. On the way home, it was clear that my mother was pleased, too, by the day’s events, but she offered no explanation for our visit to the Moon household. If she did not tell me, I knew it was not my place to ask.

The next day I was surprised when my mother sent me to a hairdresser to have my long straight black hair curled. I was even more confused to see that she had laid out her own blue suit for me to wear. It would make me look more grown up, she said. I returned with my parents to the Moons’ house. This time a large crowd had assembled. All the leaders of the church were there. I seemed to be attracting a lot of attention. Everyone smiled at me. My mother’s pretty suit, I thought. A photographer kept taking my picture. There was a mountainous amount of food.

My parents and I were soon called into a room to meet privately with the Reverend and Mrs. Moon. My parents sat on floor pillows across from the Moons. I bowed and knelt before them on the floor. The Reverend Moon was speaking so softly, I could barely hear him. I kept my head bowed. As I knelt silently before him, the Reverend Moon asked my parents to please give their daughter to the True Family. My mother and father did not look at me when they said yes.

“So that’s it,” I thought. “I’m being matched.” The Reverend Moon asked me no questions. He made no attempt to engage me in conversation, to determine what I was like. He already knew enough. The unfamiliar woman at dinner, it turned out, was a Buddhist spiritualist, a fortune-teller, who assured the Reverend Moon that I would make a perfect match for Hyo Jin. The woman whom I came to think of as the Buddha Lady was not a member of the Unification Church. It never occurred to me or my parents to ask why the Reverend Moon needed to consult a Buddhist fortune-teller for advice if he was the Lord of the Second Advent, in regular, direct communication with God.

Did I want to be matched to his son, Hyo Jin, Father asked. I did not hesitate. This was every Unification girl’s dream, to be matched to a member of the True Family. To be Hyo Jin Moon’s wife meant I would one day be the Mother of the church. I felt humbled and honored. That Hyo Jin himself was no girl’s idea of prince charming did not even occur to me. A Blessing was the uniting of two souls, not just the union of two human beings. God would turn Hyo Jin toward a righteous path, and the Reverend Moon had chosen me as an instrument of that mission. “Yes, Father,” I said, lifting my eyes to meet his. “She’s prettier than Mother,” he said. I pretended not to hear, but I could not help wondering what Mrs. Moon was thinking. I dared not steal a glance at her face.

All my life I had been told I was pretty by my family and my friends. There were girls much more beautiful than I, of course, but I knew I was pleasing to look at and it pleased me to hear the Reverend Moon say as much. I have never known exactly why Sun Myung Moon chose me to marry his eldest son. Maybe he thought I was pretty, a good student from a good family. At the time, that was explanation enough for me. As the years went on, I came to believe that my youth and naïveté were the central reasons for my selection. I was younger than Hak Ja Han was when the Messiah married her. His ideal wife was a girl young and passive enough to submit while he molded her into the woman he wanted. Time would prove that I was young, but not nearly passive enough.

Hyo Jin was waiting in an adjoining room. The Reverend Moon sent me back to see him. Both parties must agree to the Blessing, but it was not as if either of us had any real choice. We knew that the Reverend Moon frowns upon individuals selecting their own partner; matches are to be based on spiritual compatibility, not physical attraction; the Reverend Moon is better equipped than any individual to make that judgment.

I had never been alone with a boy, let alone the son of the Messiah. I bowed and greeted him stiffly as “Hyo Jin Nim.” He said I should not use the formal title Nim if we were to be married. He called me to sit by him on the couch. He held my hand. I tried to relax but I was so very shy. We had nothing to say to one another. After a few awkward minutes, Hyo Jin said we should return to his parents.

We went down to the living room, where the Reverend Moon conducted a prayer service. We all held hands. Mrs. Moon took a ruby-and-diamond ring from her own hand and slipped it onto my finger to seal our engagement. The Reverend and Mrs. Moon both cried and expressed their hope that Hyo Jin now would prove himself worthy to be the son of the Messiah.

As my parents and I left for home, my mother hit her head hard as she bent to enter the car. Ours is a superstitious culture. How many times in the years ahead would my mother and I ask each other why we had not seen that bump as a warning sign of the pain to come?

▲ I am standing outside the mansion at East Garden with my first baby.

Chapter 4

page 74

I entered the United States illegally on January 3, 1982. In order to obtain a visa, the Unification Church concocted a story about my participation in an international piano competition in New York City.

Had American immigration officials only heard me play, they would have recognized the ruse immediately. A pianist of my limited abilities would not have been among the contestants had such an event actually existed. To lend credence to the claim, the Reverend Sun Myung Moon had the best piano student at Little Angels school accompany me to New York for the same phony recital.

I confess I did not give much thought to the deceit that frigid winter day when my parents and I waved good-bye to my brothers and sisters and left for America. We accepted the Reverend Moon’s view that man’s laws are secondary to God’s plan. By his rationale, a fraudulently obtained visa was no less than an instrument of God’s design for my Holy Marriage to Hyo Jin Moon.

The truth is, I had not been thinking much at all in the six weeks since our engagement. Looking back, what I most resembled was a porcelain windup doll. Turn the key and she walks, she talks, she smiles. I was a schoolgirl, overwhelmed by the transformation I had undergone literally overnight. One day I was a child, shooed from the room whenever adults were discussing serious matters. The next day I was a member of the True Family, fumbling for the appropriate response when my elders bowed before me.

After Hyo Jin and his parents returned to America, my mother and I spent weeks shopping for a wardrobe that would match my metamorphosis from girl to woman. Gone were my school uniforms, my T-shirts and blue jeans. My teenage self was buried beneath tailored business suits and conservative sheaths. Awkward though I felt in this new role, I savored the attention. What girl would not revel in a round of dinner parties thrown in her honor? Whose head would not be turned by the solicitations of those so many years her senior?

If there was any hint of the troubles to come, it was in the discomfort I felt in the company of my intended. In December Hyo Jin Moon returned briefly to Korea, without his parents. Our meetings were strained as much by our lack of common interests as by his relentless pressure for sex. My mother had given me several books to read about marriage, but I was still unclear what the sex act actually entailed.

Hyo Jin took me to the Moon family’s home in Seoul during his visit and, under the pretext of showing me his room, cornered me by his bed. “Lie down with me,” he said. “You can trust me. We’ll be married soon.” I did as he asked, only to stiffen with fear as his clearly experienced hands groped my body and his fingers fumbled with layer upon layer of my winter clothing. “Touch me here,” he instructed, his hands guiding my own along his inner thigh. “Stroke me there.”

Sex before marriage is strictly prohibited by the Unification Church. Because Sun Myung Moon teaches that the Fall was a sexual act, incidents of premarital or extramarital sex are considered the most serious sin one can commit. Here I was, a scared and virginal girl of fifteen, having to remind the scion of the Unification Church, the son of the Messiah, that we both risked eternal damnation if I did as he demanded. He seemed more amused than angry at my righteous naivete. For my part, I believed with all my heart that God had chosen me to guide Hyo Jin away from his sinful path.

I had no idea how difficult that task would be. Even as the Korean Airlines jet landed at Kennedy International Airport in New York, I gave no thought to what my life actually would be like in America, a world away from everything I knew and everyone I loved. Humbled by my selection as Hyo Jin Moon’s bride, swept up in events being orchestrated by others, I did not ask myself how a mere mortal would fit into the “divine” family of Sun Myung Moon or how a virtuous girl could tame an older rebellious youth like Hyo Jin Moon.

As we deplaned in New York, I became separated from my parents in the crush of travelers being herded into lines for U.S. customs. The uniformed agent looked annoyed when I handed him my two large suitcases. He spoke brusquely to me, but because I did not speak English, I could not answer his questions. There was a flurry of activity and some shouting before someone came to assist me.

I watched as the customs agent dumped my neatly folded clothes onto the counter, searching the side and back pockets of my luggage. What was he looking for? What would I have?

It did not occur to me that the customs agent had reason to be suspicious. Where was my sheet music for this piano competition? Why had I packed so much for such a brief trip? Wasn’t I wearing thousands of dollars’ worth of necklaces given to me as engagement gifts in Korea? Hadn’t church leaders told me to hide them beneath my sedate brown dress?

I was arriving in the United States at the height of American antipathy toward Sun Myung Moon. He was reviled in the United States as a public menace on the order of the Reverend Jim Jones, the leader of the Peoples’ Temple cult who, in 1978, had fed more than nine hundred of his followers cyanide-laced fruit juice in a mass suicide in Guyana. The newspapers in America were full of stories about young people being brainwashed into following Sun Myung Moon. A cottage industry of “deprogrammers” had sprung up across the country, paid by parents to kidnap their children from Unification Church centers and “reeducate” them.

Having been born into the Unification Church, I knew little firsthand about the recruitment techniques that had made the church so controversial. I was skeptical about such melodramatic descriptions as “brainwashing,” but it was certainly true that new members were isolated from old friends and family. Church members were encouraged to learn as much as possible about new recruits in order to tailor an individual approach to win him or her over to the Unification Church. Members would “love bomb” new recruits with so much personal attention it is hardly any wonder that vulnerable young people responded so enthusiastically to their new “family.”

It was a recruit’s old family that usually suspected sinister motives in this all-embracing religious community. The year I came to America, it was not uncommon for travelers to be approached at airports, at traffic signals, or on street corners by young people selling trinkets or flowers for the Unification Church. Begging is hard and humiliating work and followers of Sun Myung Moon did it better than most. Asking for money is easier when you believe your panhandling is going to support the work of the Messiah.

The American government had as many questions about Sun Myung Moon’s finances as American parents had about his theology. Senator Robert Dole, the ranking Republican on the Senate Finance Committee, had concluded hearings on the Unification Church with a recommendation that the Internal Revenue Service investigate the tax status of the Reverend Moon and his church. Only a month before my engagement, a federal grand jury in New York had indicted the Reverend Moon, charging him with evading income taxes for 1972 to 1974, as well as conspiracy to avoid taxes. No doubt that indictment had more to do with the scrutiny I received at JFK International Airport than the size of my suitcases did.

I knew none of that then, of course. I knew only that I was coming to America to join the True Family. Hyo Jin Moon paced impatiently outside the customs area. As I emerged, shaken from my ordeal, I looked around for the reassurance of my parents, but Hyo Jin hustled me to the parking area and his black sports car, an engagement gift from his father. He carried a small bouquet of flowers but was so exasperated by the delay he almost forgot to give them to me. My parents would meet us at East Garden, he said. I was too tired to object.

It was a silent, forty-minute drive north from New York City to Westchester County, through the wealthy suburbs where Manhattan’s corporate executives and professional elite make their homes in quaint, rural towns along the Hudson River. It was late. It was too dark to see much and I was too tired to care.

I paid more attention as we drove through the black, wrought iron gates. This was East Garden, at last. Hyo Jin acknowledged the guard at the security booth and headed up the long, winding driveway. Even in the dark, I thought I could make out the exact spot on the rolling lawn that I had gazed at reverentially for so many years. In our home in Korea, my family displayed a photograph of the True Family, seated on the emerald green grass of their American estate. I used to stare at that photograph, unshakable in my belief in the perfection of the individuals pictured there. In their expensive clothes, posed in front of their magnificent mansion, they represented the ideal family we prayed to emulate. I treasured that photograph the way other teenagers treasured photographs of rock ’n’ roll stars.

The Reverend and Mrs. Moon and the three oldest of their twelve children greeted us at the door. I bowed down to Father and Mother, humbled to be in their home. I listened for the sound of another car as I was led through the enormous foyer into what they called the yellow room, a beautiful solarium. Where were my parents? When would they and the church elders come? Surely I would not have to converse alone with the Reverend and Mrs. Moon!

As I entered the house, I stopped to take off my heavy winter boots. In Korea one never enters a home without first removing one’s shoes. It is a sign of respect as well as an act of fastidiousness. Hyo Jin’s sister, In Jin, stopped me. I should not keep her parents waiting. In the yellow room, we exchanged pleasantries about my trip. I smiled and said little, keeping my eyes downcast. It is impossible to overstate the level of my nervousness. I had never been alone in the company of the True Family. I was nearly paralyzed by a mixture of fear and reverence. I was relieved to hear the slam of a car door signaling the arrival of my parents.

While our parents conversed downstairs, Hyo Jin took me on a brief tour of the mansion. As large as it was, the house seemed to be bursting with children and their nannies. When I arrived in America, Mrs. Moon was pregnant with her thirteenth child. Most of the little ones and their baby-sitters were asleep that night in their barracks-like quarters on the third floor. Seeing them tucked in their beds made me ache for my own younger brothers and sisters back home in Korea, especially the youngest, Jin Chool, who was six years old.

It was well past midnight when we said good night to the Moons and a driver took my parents and me to Belvedere, the church-owned estate a few minutes from East Garden where guests often stayed. First my parents were shown to a room, then I was escorted down the hall to the most beautiful bedroom I had ever seen. Decorated in shades of pink and cream, the room was fit for a princess. In addition to the queen-sized bed, the room had a living area with a large couch and comfortable armchairs. It had a crystal chandelier and two walk-in closets bigger than some of the rooms we rented in Seoul when I was small. The bathroom was enormous, its original blue-and-white hand-painted tiles retaining the elegance of the 1920s, when the mansion was built.

I had never seen such a room. There was even a television set. I fumbled with the controls, and though I did not understand a single English word, I quickly discerned that I was seeing some kind of advertisement. I wish I had a photograph of my expression when I realized that I was watching a commercial for dog food. Special food for dogs? I was transfixed by the scene of a dog scampering across a kitchen floor to a bowl full of brown nuggets. In Korea, dogs eat table scraps. I fell asleep on my first night in America in a state of wonder — I was living in a country so rich that dogs had their own cuisine!

In the morning a driver returned to take my parents and me to the Moons’ breakfast table in the wood-paneled dining room at East Garden. This is where the Reverend Moon conducts his business and church affairs. Every morning leaders come here to report to him in Korean about his financial enterprises around the globe. At the long rectangular dining table, the Reverend Moon decides what projects to fund, what companies to buy, what personnel to promote or demote.

The Moon children do not eat their meals with their parents. They appear at the breakfast table to bow to the Reverend and Mrs. Moon each morning to begin their day. Then they are led away to the kitchen, where they are fed before school or playtime. On this morning, the older children joined their parents and mine for breakfast. I caught sight of the little ones peeking through the kitchen door to steal a glimpse of me, their new sister. I felt warmed by their giggles but shocked to learn that the younger Moon children did not speak Korean.

The Reverend Moon teaches that Korean is the universal language of the Kingdom of Heaven. He has written that “English is spoken only in the colonies of the Kingdom of Heaven! When the Unification Church movement becomes more advanced, the international and official language of the Unification Church shall be Korean; the official conferences will be conducted in Korean, similar to the Catholic conferences, which are conducted in Latin.” I knew that members around the world were encouraged to learn Korean, so I was confused by the failure of the Reverend and Mrs. Moon to teach their own children what I had been taught was the language of God.

I was overpowered that morning by the strange smells of an American breakfast. There was bacon and sausage, eggs and pancakes. The sight of all that food made me slightly nauseous. In Korea I was accustomed to a simple morning meal of kimchi and rice. Mrs. Moon had instructed the kitchen sisters to serve papaya, her favorite fruit. She knew I would never have tasted such an exotic delicacy and she kept urging me to try some. She showed me how to sprinkle the fruit with lemon juice to enhance the flavor, but I simply could not eat. She looked displeased. My mother ate the papaya placed before me and praised Mrs. Moon for her excellent choice.

The Reverend Moon sensed my unease. He spoke directly to Hyo Jin: “Nansook is in a strange place, in a foreign country. She does not speak the language or know the customs. This is your home. You must be kind to her.” I was so grateful to have my fears acknowledged by the Reverend Moon that I only vaguely noticed that Hyo Jin said nothing in response.

Hyo Jin did come to see me at Belvedere but his few visits were not reassuring. They only reinforced how ill-suited we were to one another. I was afraid of him. He would try to embrace me and I would pull away. I did not know how to be with a boy, let alone with a man I was soon to marry. “Why are you running away from me?” he would ask. How could I tell him what I was too young to understand myself? I was honored to be the spiritual partner of the son of the Messiah but I was not ready to be the wife of a flesh-and-blood man.

I passed through the next four days as if in a series of dream sequences. I moved from scene to scene, numb from exhaustion and the magnitude of unfolding events. I went where I was directed. I did as I was told, concerned only that I make no mistakes that would displease the Reverend and Mrs. Moon.

Mrs. Moon took my mother and me shopping at a suburban mall. I had never seen so many stores. Mrs. Moon gravitated to the most expensive shops. At Neiman-Marcus she selected unflattering, matronly dresses in dark colors for me to try on. She chose bright red or royal blue outfits for herself. I suspect that she resented my youth. She had heard her husband on my engagement day say that I was prettier than she. It was hard for me to imagine a woman as stunning as Hak Ja Han Moon being jealous of anyone, especially a schoolgirl like me. She had been only a year older than I when she married Sun Myung Moon. At thirty-eight, pregnant with her thirteenth child, she still had the flawless skin and facial features of a great beauty.

She was outwardly generous to me, summoning me to her room that first week to give me a dress she no longer wore and a lovely gold chain. I took the chain off in her bathroom as I tried on the dress and mistakenly left it on the sink. She sent her maid to me later at Belvedere to give me the necklace. Mrs. Moon opened her closet and her purse to me, but from the very first, I felt she closed her heart.

The position of first daughter-in-law in a Korean family is, by tradition, an exalted one. She will inherit the role of mother and be the anchor of the family. There is even a special term for first daughter-in-law in Korean: mat mea nue ri. It was clear from the beginning that I would not fill this role in the Moon family. I was too young. “I had to raise Mother and now I have to raise my daughter-in-law, too,” the Reverend Moon always said. It was only later that I recognized that no outsider would have been allowed a key role in the Moon family. As an in-law, one had to know one’s place. For me that meant when the family was gathered, being the last person to sit in the seat farthest away from Sun Myung Moon.

Given the attention of customs officials that I had attracted at the airport, the Reverend Moon decided it would be prudent to stage a piano recital after all. I was in a panic. I had not practiced. I had brought no music with me. My mother assured me that I could get by with a Schumann piece I had memorized for class at Little Angels. I thought perhaps I remembered it well enough. Hyo Jin and Peter Kim, the Reverend Moon’s personal assistant, drove me into New York City one afternoon to give me a chance to practice on the stage of Manhattan Center, the performing arts facility and recording studio owned by the church in midtown, where the recital would be held.

I sat alone in the backseat of one of the Reverend Moon’s black Mercedes, staring out at the city as its skyscrapers came into view. I knew I should be impressed, but it was a cold, gray January day. My only impression was how lifeless New York City seemed. In retrospect, that dead feeling may have had more to do with my own emotions; they were as frozen as the concrete landscape outside my window.

At Manhattan Center, we met Hoon Sook Pak, the daughter of Bo Hi Pak, one of the highest-ranking officials in the church. She was Hyo Jin’s age; he had lived with her family in Washington, D.C., during his tumultuous middle-school years. She would later become a ballerina with the Universal Ballet Company, Korea’s first ballet troupe, founded by Sun Myung Moon. They greeted one another warmly in English, though both spoke fluent Korean. I stood there mute while they chatted at great length. I could feel my cheeks burn. Why were they ignoring me? Why were they being so rude? I got even angrier when Hyo Jin left me in a small anteroom while he went to talk to some other people. “Stay here,” he instructed as if I were a puppy he was training to obey.

I felt a surge of that familiar stubborn pride that had provoked so many childhood arguments with my brother Jin. As soon as Hyo Jin was out of sight, I went exploring. The performing arts center is adjacent to the old New Yorker Hotel, now owned by Sun Myung Moon. The church uses the hotel to house members. The entire thirtieth floor is set aside for the True Family, to accommodate them on their overnight stays in New York City. I wandered around, jiggling the doorknobs of locked rooms.

Hyo Jin was furious when he returned to find that his pet had not stayed put, as ordered. “You can’t just go off like that. You are in New York City. It’s dangerous,” he screamed. “Someone could have kidnapped you.” I said nothing but I thought, “Pooh! Who would kidnap me?” Mostly I hated that this rude boy thought he could tell me what to do.

Hundreds of church members filled the concert hall on the night of my performance. I was a small part of the evening’s entertainment. I was the third of several pianists to play. I wore a long pink gown that my mother had bought for me before we left Korea. My stomach was doing somersaults, whether from the sushi I’d eaten at lunch or from the prospect of performing for the True Family, who were seated in the theater’s VIP box. In Jin, Hyo Jin’s sister, spooned out Pepto-Bismol for me to drink. It worked. I thought of that pink liquid as I did dog food: one of the wonders of America.

I played too quickly. The audience did not know I was done, so there was a delay in the applause. I was just relieved that I had made it through the piece and only missed a few notes. As soon as I got backstage, Hyo Jin and In Jin told me to change into my street clothes. I did as they said, not realizing there would be a curtain call for all the performers at the end of the evening. I could not go onstage dressed so casually, so I took no bows with the others.

In the Moons’ suite in the New Yorker after the show, the Reverend Moon was so pleased with the evening that he decided that a real piano competition should be an annual event. Mrs. Moon, however, was icy toward me. “Why didn’t you take your bow with the others?” she snapped. “Why did you change your clothes?” I was taken aback. What could I say? That I had done as her son instructed? Hyo Jin watched me squirm and said nothing. I just bowed my head and accepted my scolding.

My failure to appear for the curtain call was not my first infraction, it turned out. Mrs. Moon had been keeping track of my missteps. She enumerated them all for my mother the next day. I had been rude to enter their home wearing my boots; I had been careless to leave the necklace on the sink; I had been ungracious not to eat heartily at mealtime; I had been thoughtless not to take a bow at curtain call. In addition, she told my mother, Hyo Jin complained that my breath was stale. Mrs. Moon sent my mother to me with words of caution and a bottle of Listermint mouthwash.

I was devastated. If first impressions were the most lasting, my relationship with Mrs. Moon was doomed my first week in America.

The wedding was set for Saturday, January 7, in order to accommodate the school schedules of the Moon children. There was no marriage license. We had had no blood tests. I was a year below the legal age to marry in New York State. My Holy Wedding to Hyo Jin Moon was not legally binding. Not that I knew that, or cared. The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s authority was the only power that mattered.

We attended breakfast with the Reverend and Mrs. Moon in the morning. My mother urged me to eat. It would be a long day. There would be two ceremonies. A Western ritual would be held in the library of Belvedere. I would wear a long white dress and veil. Afterward there would be a traditional Korean wedding, for which Hyo Jin and I would wear the traditional wedding clothes of our native country. A banquet would follow in New York City.

My mother asked Mrs. Moon if I might have a hairdresser arrange my hair and apply my makeup. A waste of money, Mrs. Moon said; In Jin would help. I worshiped In Jin as a member of the True Family, but I was not so certain I trusted her to be my friend. She did as her parents asked, winning their praise for her kindness to me, but I could see that I was no more her type than I was Hyo Jin’s. As she dusted my face with powder, she offered me some advice. I would have to change, and fast, if I was going to fit in with the Moon children, especially my husband. “I know Hyo Jin better than anyone,” she told me. “He does not like quiet girls. He likes to have fun, to party. You need to be more outgoing if you want to make him happy.”

Hyo Jin looked pleased enough when he stopped by to see me just before the ceremony, but I knew I was not the source of his happiness. On this day he would be his father’s favorite, the good son, not the black sheep. He even agreed to trim his long shaggy hair to please his parents.

As I walked alone down the long hallway that led to the library and my future, an old Korean woman whispered to me, “Don’t smile or your first child will be a girl.” That was an easy instruction to follow, and not just because I knew the great disappointment that greeted the birth of females in my culture. My wedding day was supposed to be the happiest day of my life, but all I felt was numb. I want to weep for the girl I was when I look at the photographs in my wedding album. I look even more miserable in those pictures than I remember feeling.

There was a crush of people on both sides of me as I entered the library and made my way across the room to the Reverend and Mrs. Moon in their long white ceremonial robes. The library was very hot, packed with people, all of whom were strangers to me except for my parents. It was an impressive room, its dark wood-paneled walls lined with old, unread books, its high ceilings hung with chandeliers. It was hard not to believe in that setting that I was fulfilling God’s plan for me and for the future of the True Family charged by him with establishing Heaven on earth. I was an instrument of his larger purpose. The marriage of Hyo Jin Moon and Nansook Hong was no silly, human love match. God and Sun Myung Moon, by uniting us, had ordained it.

It was a smaller group of family and church leaders who attended the Korean rites upstairs in Belvedere. I was learning that the Moons do the most momentous things in life in a hurry, so I barely had time to arrange my hair in the traditional style before I was summoned. I forgot to dot my cheeks in red in the customary manner, a failure noted by Mrs. Moon and the ladies who surround her. Hyo Jin and I stood before True Parents at an offering table laden with food and Korean wine. Fruits and vegetables were strewn beneath my skirt as part of a folk tradition meant to symbolize the bride’s desire to produce many children.

I remember little of the actual ceremony. I was so tired that I relied on the flash of the official church photographer’s camera to keep me focused. I was grateful for orders to “stand here” or to “say this.” If I kept moving, I would not collapse.

A driver took Hyo Jin and me back to East Garden to change our clothes for the reception that would be held in the ballroom of Manhattan Center. He delivered us to a small stone house up the hill from the mansion. With its white porch and charming stone facade, it looked like something out of a fairy tale. This is where Hyo Jin and I would live. We called the place Cottage House. There was a living room, a guest room, and a small kitchen on the first floor. Upstairs was a small bathroom and two bedrooms. Our suitcases, I saw, had been delivered to the larger of the bedrooms.

Hyo Jin insisted that we have sex. I begged him to wait until the night — True Parents expected us to be ready to leave within the hour — but he would not be put off. I did not want to be naked in front of him. I slipped into bed to remove my clothes, a practice I would continue for the next fourteen years. I had read the books my mother gave me, but I was totally unprepared for the shock of sexual intercourse. When Hyo Jin got on top of me I did not know what to expect. He was very rough, excited at the prospect of deflowering a virgin. He told me what to do, where to touch. I just followed his directions. When he entered me, it was all I could do not to cry out from the pain. It did not take very long for him to finish, but for hours afterward, my insides burned with pain. “So this is what sex is,” I kept thinking.

I began to cry, from pain, from exhaustion, from shame. I felt we were wrong not to wait. Hyo Jin kept trying to shush me. Didn’t I enjoy it? he wanted to know. It was very “ouchy,” I told him, using a little girl’s word for a woman’s pain. He said he’d never heard that reaction before, confirming all the rumors I had heard in Korea. Hyo Jin had had many lovers. I was shocked and hurt that he would confess his sin in such a callous and cavalier way. I wept even harder, until his sharp tone and angry rebuke forced me to dry my tears. At least I now knew what sex was and who my husband was. It was horrible; he was no better.

While we were dressing, a kitchen sister called to say that True Parents were waiting for us in the car. We rushed downstairs and into the front seat of a black limousine. Mrs. Moon looked at me accusingly. “What delayed you?” she snapped. “There are people waiting.” Hyo Jin said nothing, but our flushed faces and hastily arranged clothing made our actions evident. I was glad the Moons were in the backseat so that they could not see my shame.

I fell asleep on the drive into Manhattan but my rest was short-lived. The ballroom of Manhattan Center was filled with banquet tables and hundreds of people, most of them American members. They cheered as we entered and took our seats at the head table. I was tired of all the hoopla, but there still were hours of entertainment and dining ahead of me. It was an American meal of steak and baked potatoes and ice cream and cake. My mother urged me to eat, but everything tasted like sand. Despite the Korean flavor of the entertainment, the entire evening was conducted in English. I understood not a word of the many speeches and toasts raised in honor of Hyo Jin and me. I smiled when the others smiled and applauded when the others did likewise.

The language barrier had the effect of making me a spectator at my own wedding. I was in this group but not part of it. I looked around at all the Moons singing, clapping. Everyone looked so happy. It was pretty exciting to watch. I was yanked out of my isolation when my father, who also did not understand English, told me he suspected I would be asked to make some brief remarks. “In English?” I asked, terrified. “No, no,” my father reassured me. “Hyo Jin will translate for you.” My father told me to keep it short, to thank God and the Reverend Moon and to promise to be a good wife to Hyo Jin. When the time came I did as my father said. The room erupted in shouts of “What did she say?” from the non-Korean audience. “Oh, it was nothing important,” Hyo Jin told them as he went on to make his own remarks in English to tumultuous applause.

I kept my hands in my lap as I clapped. The Reverend Moon instructed me to lift them onto the table and told me to applaud more openly to demonstrate my joy on my wedding day and my appreciation of Hyo Jin. I did as he instructed, thinking all the while: “I am such an idiot. Can’t I do anything right?”

The festivities did not end even after we returned to East Garden. It is a Korean tradition for wedding guests to strike the soles of the groom’s feet with a stick for his symbolic thievery of his bride. Back at Cottage House, Hyo Jin put on several pairs of socks in preparation for this ritual assault. The Reverend and Mrs. Moon laughed as church leaders tied Hyo Jin’s ankles together so he could not escape. Every time they hit Hyo Jin’s feet Father would express mock outrage: “Stop, I will pay you not to hit my son.” Those wielding the stick would take his money and resume their beating. “I’ll give you more money if you stop,” the Reverend Moon would shout and again the laughter would begin as they stuffed Father’s money into their pockets and began hitting Hyo Jin again.

I watched the proceedings from a soft armchair that threatened to swallow me straight into sleep. Everyone commented on my calm demeanor. “She does not cry out to them to stop hitting her husband.” I was not calm; I was numb. At the urging of the crowd, I tried to untie his ankles but I was so tired Hyo Jin had to do it himself.

The next morning we all gathered at the Reverend Moon’s breakfast table. Hyo Jin disappeared early, I don’t know to where. I stayed to wait on the Reverend and Mrs. Moon. I was not certain what my role should be in the True Family, and my new husband was little help in guiding me. I fell naturally into the role of handmaiden to Mrs. Moon.

It was not until after the wedding that anyone suggested to me that Hyo Jin and I might take a honeymoon. He wanted to go to Hawaii, but the Reverend Moon suggested Florida instead. Ours was not a conventional wedding trip. We made an odd threesome: husband, wife, and personal assistant to Sun Myung Moon. The Reverend Moon had handed his assistant, Peter Kim, five thousand dollars, with instructions to drive us to Florida. No one told me where we would be going or what we would be doing. My mother, accustomed to the formality of East Garden, packed a suitcase full of prim dresses for me, and I tossed in a single pair of blue jeans and a T-shirt.

Peter Kim and Hyo Jin sat in the front seat of the blue Mercedes. I sat alone in the back. They spoke in English for the eleven-hundred-mile trip down the East Coast. My sense of isolation was complete. The two men decided where and when we would stop to eat or sleep. I remember fighting off tears at a gas station rest room. I could not figure out how the hand dryer worked. I thought I had broken it when it would not stop blowing hot air. It was a small moment, but a lonely one. Such a simple thing and I had no one to ask for help.

I brightened a little when we arrived in Florida and Peter Kim suggested taking me to Disney World. I was a fifteen-year-old girl. I could not imagine a more wonderful vacation spot. Hyo Jin was unenthusiastic. He had been there many times before. He reluctantly agreed to stop in Orlando. It was cold. A light drizzle was falling, but I did not care. I walked down Main Street USA toward Cinderella’s castle and understood exactly why they call Disney World the Magic Kingdom. I kept my eyes peeled for Mickey Mouse or any of the familiar costumed characters, but I would not have an opportunity to see any of them. Ten minutes after we arrived, Hyo Jin declared that he was bored and wanted to leave. I was astounded by his selfishness, but I followed a few steps behind as he led the way back to the Mercedes.

The Reverend Moon had suggested we drive to give me a chance to see some of the United States, but Hyo Jin soon ran out of patience with that plan as well. He summoned a security guard from East Garden to fly down to Florida to pick up the car. We were flying to Las Vegas, he told me.

I had no idea where or what Las Vegas was and neither Hyo Jin nor Peter Kim bothered to enlighten me. Neither did they tell me that the Reverend and Mrs. Moon and my own mother and father were vacationing there. I did not know we would be joining our parents until we walked across the hotel restaurant to the table where they were seated. My mother chastised me for gazing distractedly around the room as I walked toward them. It would only have been disrespectful, I told her, if I had known that the Moons were there and I did not!

I was all the more confused when I learned that Las Vegas is a gamblers’ paradise. There were slot machines in the restaurants, casinos in the hotels. What were we all doing in a place like this? Gambling is strictly prohibited by the Unification Church. Betting of any kind is seen as a social ill that undermines the family and contributes to the moral decline of civilization. Why, then, was Hak Ja Han Moon, the Mother of the True Family, cradling a cup of coins and feverishly inserting them one after another into a slot machine? Why was Sun Myung Moon, the Lord of the Second Advent, the divine successor to the man who threw the money changers out of the temple, spending hours at the blackjack table?

I dared not ask, but I did not need to. The Reverend Moon was eager to explain our presence in a place I had been taught was a den of sin. As the Lord of the Second Advent, he said, it was his duty to mingle with sinners in order to save them. He had to understand their sin in order to dissuade them from it. I should notice, he said, that he did not sit and bet at the blackjack table himself. Peter Kim sat there for him and placed the bets as the Reverend Moon instructed from his position behind Peter Kim’s shoulder. “So you see, I am not actually gambling, myself,” he told me.

Even at age fifteen, even from the mouth of the Messiah, I recognized a rationalization when I heard one.

▲ I am holding our first baby, and Hyo Jin is holding the youngest child of Sun Myung Moon.

Chapter 5

page 94