Mitchell was a lucky one—he got away from the Unification Church

Palm Beach Daily News By Vicki Salloum November 14, 1976

Mitchell Mack Jr. was lucky. On July 26, the 23-year-old North Carolinian was kidnapped in the corridor of a San Francisco hotel by a six-man team of policemen, lawyers and deprogrammers. He was led in handcuffs to a police car and later taken to a series of Midwestern rehabilitation centers.

Mitch was one of the lucky ones. He broke the strangle-hold of the Unification Church, whose brain-washing tactics he relates, have induced even licensed physicians to forsake their practices to sell flowers on the streets.

Some disillusioned young cultists reportedly have been driven to the brink of suicide, or complete mental collapse.

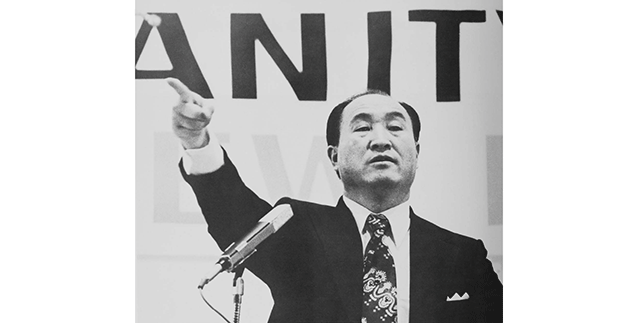

The leader of the church and the self-proclaimed Lord of the Second Advent is Rev. Sun Myung Moon, a wealthy Korean industrialist whose special blend of evangelical Christianity and Oriental shamanism has earned him a personal annual income of $30 million—raised from the sweat of his fund-raising teams alone—enabling him to live in baronial splendor on a $625,000 estate in Irvington, N.Y.

Last winter, workers for the Rev. Sun Moon made inquiries about buying a Palm Beach estate, priced at over $1 million, for their leader. Rev. Moon, they said, would be coming up from Miami aboard his 75 foot yacht to inspect the property. But the owner refused to sell the estate to them.

Published estimates of the size of Moon’s American following range from 3,000 to 30,000 and include doctors, lawyers, scholars. The following also includes a youth whose father controls the fishing industry in South Africa, and a man who left the diplomatic corps in Washington (at the time of Mitch’s capture) to join the cult.

There is one less “Moonie” around today. In a telephone interview this week, Mitchell Mack—my cousin—related to me his journey from the land of Sun Myung Moon.

His spiritual odyssey began on a chilly afternoon in April 1975 when Mitch—donning jeans and a light leather coat, with his beard and shoulder-length hair—strolled down a street in Berkeley, California. A girl with a glassy, far-away look in her eye caught his attention.

“Hi,” she greeted him. Mitch kept walking. Another girl ran up to him, introduced herself as Juliet, and invited him to dinner with “a bunch of people trying to live better lives.” Mitch listened but made no commitment.

Two days later, Juliet called to again invite him to dinner. (There was never any mention of the Unification Church.) Mitch accepted. He wanted to explore the psyche of the California people.

A recent college graduate from an upper middle class family who didn’t know what he wanted to do with his economics degree, Mitch had spent the winter in Colorado and Wyoming trying to “find some answers, and share new experiences.”

For several years he had been an avid reader of Western philosophical and religious thought, which seemed to indicate to him that now is the incubation period for a new age. While in California, where he planned to spend a month before heading home, he had come in contact with members of such religious cults as Hare Krishna, Every Man Theater, Divine Light Mission and Church of Scientology.

“In every instance,” said Mitch, “it seemed like someone at the top was selling happiness.”

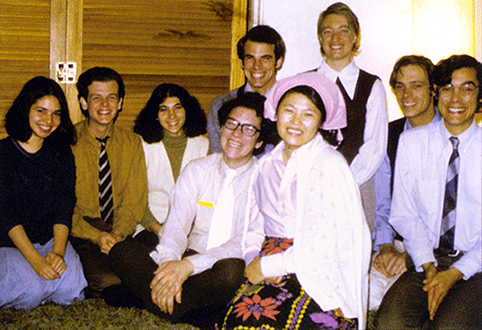

At dinner in the Moonie home, three youths stayed with Mitch at all times. They struck him as strange, overly zealous, excessively cheerful youths who, nevertheless, preached Christian ideals of love and human responsibility.

“It was all very surreal,” he recalls. “I told myself not to take things at face value. I thought, ‘I can’t let my arrogance stand in the way of opening myself up to everybody.’ At the time, I was interested in setting up a collective community and also seeing the northern California countryside.”

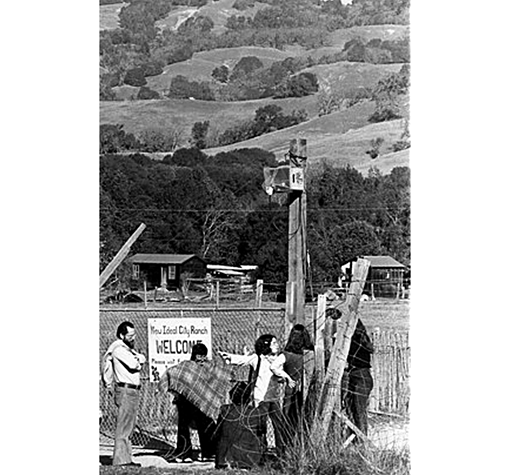

The following weekend, Mitch was taken to a converted chicken coup called the New Ideal City Ranch at Boonville, California, the Moonie indoctrination center.

There were non-stop lectures. Recruits were harangued about the need for reform in a spiritually and socially decadent world and asked how they could reject the world and turn their backs on God, and then told they could make the world a better place by joining the cult.

Moonies were with Mitch constantly, rarely leaving him time alone with his thoughts, or giving him time to evaluate the endless propaganda being thrown at him. There was a dizzying strain and excitement that made everyone extremely emotional and at the same time clouded the thinking processes, making logic vague and understanding difficult, Mitch remembers.

Mitch had been with the cult about 10 days when he first heard the name Sun Myung Moon. It made no impact on him since he had never heard of the Unification Church or its leader.

Around that time, Moonies began dropping hints of the existence of a Messiah who would restore the world to an eternal and perfect Garden of Eden.

In enticingly secretive tones, they would speak of the Lord of the Second Advent, born between 1917 and 1920, who came from the East.

“Several days later, I found out that Sun Myung Moon is a Korean who was born in 1920,” Mitch relates. “I made inquiries as to whether Moon was the Messiah. In round-about statements, the Moonies indicated he was.”

“You can’t believe what the messianic principle does to your psyche,” he continued. “When you’re led to believe that the world is doomed and then you’re suddenly confronted with a Messiah who will usher in a new age on earth, an era of eternal happiness—the impact is devastating.”

Mitch, who became captain of a six-member mobile fund-raising team, worked 19 hours a day. The crew begged $2,000 a day in exchange for flowers. Some nights they barely got two hours sleep.

It has been estimated that Moon makes a cool $1 million a week, but not even the Messiah himself knows the vast extent of his operation.

Two secret Berkeley-based enterprises are the International Exchange Maintenance Company and a Jewish delicatessen named Aladdin’s restaurant, both owned by Onni-cohort, Jeremiah Schnee. Both are highly successful businesses run off the sweat of Moonie labor.

The proceeds from these businesses go to buying Onni Durst gifts. As Mitch tells it, disciples once bought Onni a $27,000 Mercedes, tied a ribbon around the new car and parked it on the grounds of her $45,000 Berkeley estate. “It’s the wrong color,” Onni scoffed, after inspecting the gift. “Take it back.” Instead, the cultists gave the car to Moon and bought Onni another one—this time in the right color.

In other instances, various fund-raising teams have given Onni an 11-carat diamond ring worth $75,000 and a $1,800 mink stole. “She didn’t even say thank you,” said Mitch, referring to the mink. “She already had three.”

In an attempt to stifle growing criticism of the church’s slave labor tactics, Jeremiah Schnee now issues salary checks to his restaurant employees. The Moonies endorse the checks, return them to Schnee, who gives them to Onni to be used as her personal spending money.

Why do Moonies tolerate such behavior from their leaders?

Moonies have been taught to reject their real parents, Mitch explains. Thus, church leaders become surrogate parents to the Moonies and the object of their guilt-motivated generosity.

Mitch compares the hypnotic, save-the-world fervor of Sun Myung Moon to that of Adolph Hitler.

“Are you willing to serve God and make the world a better place?” Moon once beckoned a crowd of worshippers. “Yes,” they answered in unison. “Are you willing to do anything for God and True Parents (Moon and his wife)?” his voice rose higher. “Yes! Yes!” they chanted. “Would you be willing to kill for God and True Parents?” Moon thundered. “Yes! Yes! Yes!” they screamed.

“There are people in that church who would have killed for him,” Mitch contends. “I can’t honestly say what I would have done.”

In June 1976, 14 months after Mitch drifted into the cult, the Macks became convinced their son no longer was in control of his mind.

Mitch had sold his car for $900 before leaving home. He also had $600 and two credit cards. Within the next few months, all his money and some $600 more in credit-card charges went into his work.

Mitch called and asked his dad to transfer $2,000 more of his savings into checking, saying he wanted to give it to the church. His father refused, encouraging him to come home and talk about it.

The Macks wanted their son home. They ran up some fantastic telephone bills, they argued, they cried, and members of the family visited him. Mitch’s younger brother, Ron, traveled throughout the country to learn from experts more about the church and mind-control.

Ron learned that lawyers in Phoenix, Ariz., had used a conservatorship approach to legally remove young people from another cult there. Papers were drawn declaring Mitch, the eldest of five children, a suspected victim of mind control, giving his parents power to hold him 30 days.

The recovery plan evolved. Mitch’s aunt was to be in San Francisco in late July. Arrangements were made to arrest Mitch while he had dinner with his aunt at her hotel.

“I was very nervous that morning.” Mitch relates. “I knew I was going to be kidnapped. When I saw the conservatory team, I started pushing and shoving. They put the handcuffs on me. Rene (a Moonie who accompanied him to the hotel) sort of freaked out. But no one laid a hand on her.”

Two days later, Rene filed suit for $1 million charging the conservatory team had physically abused her.

It took the team three days to break the mind control, and Mitch was taken to various centers in the Midwest to complete the process of rehabilitation. The Mack family’s investment in recovery cost more than Mitch’s four-year college education.

“I’m not resentful of anybody (in the Moon family),” said Mitch, who will be touring the college circuit to lecture on mind control. He also plans to enter graduate studies in theology and later to attend law school. “They are the finest people I’ve ever met. I know they are enslaved. They are just completely brainwashed.”

Mitchell Mack Sr., a department store owner in North Carolina, is convinced the Moon organization, and cults of its genre, are dangerous.

“The amazingly complex and expensive process of getting my son back made me aware of mind-control I didn’t believe possible,” said Mack.

“I’m convinced we’re going to see some horrendous problems among these young people who recognize their idols as frauds, and realize what they’ve done to themselves and their families.”

Meanwhile, the church continues as one of the major growth industries in the United States.

Attention has been focused on the church’s $24 million holdings of real estate (mainly in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles), which includes the former New Yorker Hotel, the former Columbia University Club, and 350 acres of Tarrytown land.

▲ 4 West 43rd Street, the former Columbia University Club

▲ 4 West 43rd Street, the former Columbia University Club

And it is publicly known that Moon and 22 of his associates had spent $1,232,000 last fall to acquire 51 percent of the stock of a newly formed Washington, D.C., institution called the Diplomat National Bank.

Still, Moon has been beset with a powerful downward momentum and, in September, the Messiah reportedly fled to Germany, claiming his four-year ministry in the United States had ended. (Moon founded the church in Seoul in 1954 but came to the United States in late 1971 to take charge.)

“I interpret his leaving to mean that investigators in Washington are closing in a bit,” said Rabbi Maurice Davis, a prominent spokesman for the anti-Moon forces who heads Citizens Engaged in Reuniting Families. “I suspect that‘s the reason he got the hell out of here.”

“The future of the church depends on what happens in Washington,” said Rabbi Davis, contacted by phone in White Plains, New York. “If these investigations get off the ground, it will strike a body blow to the movement. But it doesn’t minimize the danger right now to every young person.”

“Onni Durst is a woman of guts. While she was at a slot machine in Las Vegas, she completely ran out of coins; she went to the next person, smiled, and borrowed some coins.”

Sun Myung Moon (May 19, 1980, New York City)

Guests had their passports stolen

A former US member: “I recently [July 2015] had one of my neighbors reveal to me that he … had stolen my passport and ID from my luggage under direction from Noah Ross at Camp K in [Northern California – the Oakland family]. This among other things, resulted in my deciding to stay in the Creative Community Project for a while. Well… 25 years or more to be exact. He also told me that Noah, Jennifer and Nicolas routinely got him and others to do the same to all of the foreign workshop guests at Camp K. This wasn’t provided in the manner of a tearful confession but rather like a boast in order to have a dig at my expense.”

Moonwebs – Journey into the Mind of a Cult by Josh Freed

Barbara Underwood and the Oakland Moonies

Crazy for God – The nightmare of cult life

by ex-Moon disciple Christopher Edwards

Life Among the Moonies – by Deanna Durham

Camp K, aka Maacama Hill, Unification Church recruitment camp

Sun Myung Moon’s theology used to control members

Allen Tate Wood on Sun Myung Moon and the FFWPU / Unification Church

Cult Indoctrination – and the Road to Recovery

The Social Organization of Recruitment in the Unification Church PDF

by David Frank Taylor, M.A., July 1978, Sociology

A Rabbi evaluates the Unification Church

My Time with the Oakland Family Moonies – by Peter from New Zealand