(Studies in Korean religions and culture)

A collection of essays edited by Chai-Shin Yu and R. W. L. Guisso

Published by Asian Humanities Press, Berkeley, California (1988)

The shamanistic tradition is closely woven into the fabric of Korean life and is even now a determinant of the Korean world-view, as well as its family and social customs at all societal levels. (page 9)

Any understanding of the so-called New Religions of Korea would be difficult without some knowledge of shamanistic influences upon them. (page 10)

An Introduction to Korean Shamanism – Chang Chu-kun

(page 30)

Shamanism is perhaps the most ancient, and in both East and West, the most ubiquitous of religious phenomena. It has often co-existed with other forms of magic, superstition and religion, so that a simple and discrete definition of its meaning and character is not easy. To compound the problem, shamanism in Korea has usually been regarded as akin to superstition, while in Japan, it was given a more respectable position as a set of public religious activities which evolved into National Shinto.

In both settings, however, Eliade’s notion of shamanism as “archaic techniques of ecstasy” seems to apply, since in most cases the shamans themselves occupy the position corresponding to “spirit” in other forms of magico-religious ecstasy and are therefore distinct from more “orthodox” religious practitioners. In the Korean case, there are regional variations so that, for instance, in the north only male shamans are regarded as being truly possessed by the spirit while in the south, the opposite is true. In Cheju Island, generally regarded as the home of the purest form of Korean shamanism, one finds unique observances and attitudes. …

A final point to be made before passing on to a brief history of Korean shamanism is that in the more primitive areas of the Korean countryside, shamanism represents even today the most basic reality of religious experience. Here, shamans assume Banzaroff’s threefold role of priest, medicine-man and prophet, and in addition, promote folk-art and folk-culture. In Cheju Island, shamanism is virtually the sole transmitter of Korean myth.

It is generally conceded that shamanism existed in the Korean peninsula well before the tenth century B.C., and archeological evidence in fact suggests that it was part of Bronze Age culture. Just as is the case today in remote areas of the countryside, shamanistic ceremonies to propitiate local gods of field and forest were held, and though in ancient times, both sexes served as shaman, today, females invariably fill this role.

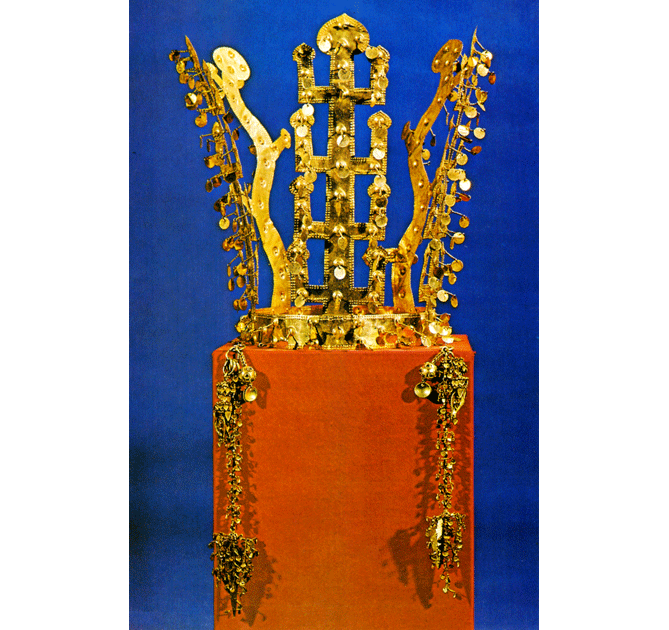

In time, the scattered communities coalesced into the kingdoms of Koguryǒ, Paekche and Silla, and it is interesting to note, as Professor W.Y. Kim assumes, that the well-known golden crowns of the Silla era were used not only as symbols of kingship, but were worn also as the sign of the chief shaman of the kingdom. Literary evidence makes it very clear that sacerdotal functions were integral to Sillan kingship and we find in the Samguk sagi for instance, that the second king of Silla, Namhae Kosogan, was also called Ch’ach’a ung or High Shaman. Contemporary Chinese sources bear out this designation and the Sankuo Chih states: “In Silla, the king was called Kosagon, or termed Ch’ach’a Ung or Ch’ach’ung”. Kim Tae-mun, an eighth-century Silla scholar commenting on the passage, suggested that, “in the national [Korean] language, “Ch’ach’a ung” means shaman.”

▲ Sun Myung Moon and Hak Ja Han wearing Silla crowns at a ceremony in their lakeside palace at Cheongpyeong. They have another palace which was built a few years later, and cost $1billion, on the hillside above the lake.

Another title for the Sillan ruler was maripkan which means, literally, “seat-marker” and refers to the marks which indicated the proper seating positions of ruler and courtiers during court ceremonials. Since these ceremonials were religious in character, the term is yet another indication of the sacerdotal role of the Sillan ruler….

Shamanism and the Korean World-View, Family Life-cycle, Society and Social Life – Hahm Pyong-choon

(page 93)

… In its interactions with Buddhism and Confucianism, Korean shamanism reinforced those beliefs and practices which were congenial to its own values. More fundamentally, the fact that neither of these religions were monotheistic or absolutist rendered their world-views basically compatible with shamanism. Although the shamanistic man is capable of accepting an absolute, monotheistic god who demands exclusive loyalty, there is a limit to his adherence to such a god: he would retain his faith only so long as the god proved to be effectual in tangible ways.

In the long run, merely abstract and intellectual experiences are insufficient for the shamanistic man. Instead, he desires sensory experience—preferably of a sort amenable to communal sharing—as proof of a god’s existence. Christian churchmen, for instance, have observed rather ruefully that Korean Christians tend to importune god for worldly benefits rather than to praise him or to pray for eternal salvation. Another tenet of Christianity, as espoused by the missionaries who spread the gospel to Korea, has been illustrated by a conversation between an American Protestant missionary and a Korean. The missionary explained his gospel and urged the Korean to become a Christian in order to avoid the horrible damnation awaiting the heathens in hell, and instead, to go to heaven for the eternal bliss in store for the Christians. The Korean responded by asking the missionary where his dead parents were, in heaven or in hell. Since they had died without becoming Christians, the missionary said, they could not have gone to heaven. As with enlightenment in Buddhism, the Korean responded that a son’s place is with his parents, be it heaven or hell, and that it would be the height of depravity for him to separate himself from all his forbears by attaining an individual salvation. The refusal of Christianity to make any doctrinal modifications for the sake of its Korean flock has no doubt contributed to the difficulties which Koreans have had in accepting the religion.

Modern Challenges

… The avarice of many mudangs has further aggravated the misfortunes of shamanism. Rather than providing competent service which would reinforce communal solidarity, reaffirm the joy of life, and promote the healing of psychogenic and psychosomatic illness, some mudangs intimidate people with their supposed superhuman powers for the purpose of exacting money. … luring people with promises of good fortune…

Korean Taoism and Shamanism – Yu Chai-shin

(page 112)

… Taoistic Shamanism, however, is not restricted in its strong influence to Ch’ǒndo-gyo, but is also important as an influence in other new religions in Korea. Such concepts of God as Lao Tzu’s or that of Tan’gun, some magical elements, the cure of sickness, secular blessings, etc., are to be found in various new religions. This was, perhaps, inevitable, because these elements were at the very root of popular religion and culture from early times.

It should also be noted that those new religions which found their origins in Christianity seem as well to have been greatly influenced by Taoistic-Shamanism. For example, the Rev. Yongdo Yi’s [Yong-do Lee] Christ-centered mysticism, which was characterised by erotic elements, seems to have been influenced by the Yin-yang principles so prominent in Taoism, and the same principles also seem to have influenced Pak Taeseon’s “Evangelical Hall Movement”, and Moon Song-myong’s Unification Church movement. For example, Pak’s curing of sickness and driving out of devils by the laying on of hands show Christian influence, while the practice of using water for the curing of illness is a direct influence of Chinese Taoism. Moon’s Unification Church seems to have been influenced by the Yin-yang principle for sexual relations, which in turn was an influence from Yi Yongdo [1901-1933]. When Moon conducts communal marriages, he puts on a “dipper crown”, borrowing symbolism from both Taoism and Shamanism.

▲ Sun Myung Moon wearing a “dipper crown” with seven stars at a mass wedding.

The Big Dipper, (the tail of the Great Bear or Ursa Major) is referred to in Religious Taoism as the Seven Stars or the Bushel constellation. The cluster of stars commands a pre-eminent place in Taoist ritual symbology because it is believed to be the locus of yin and yang forces and therefore the controller of all order in the universe. A dipperful is a measure for dry grain, hence the alternate name for the cluster of seven stars as the Bushel Constellation

In Eastern Asia, these stars compose the Northern Dipper. They are colloquially named “The Seven Stars of the Northern Dipper” (Korean: 북두칠성(北斗七星), Bukdu chilseong).

Daoists believe that this star constellation is the seat of the celestial bureaucracy of the gods.

The Seven Stars Constellation is also said to be the chariot of the Heavenly Emperor.

… Korean Taoism, which can more accurately be described as Shamanistic Taoism, occupied the place of a state religion in Koguryǒ, Pakche and Silla until they were united by Koryo.

Taoism was incorporated into Korea in a systematic fashion and thus it influenced the thinking and practices of the people, but in spite of this, Taoism was never organized to the same degree as Buddhism.

… My own research has led me to disagree with the views of some specialists in Asian religion who suggest Buddhism as the common ground for the religions of China, Korea and Japan. Instead it appears to me that since Shamanistic Taoism was more common to the experience of the masses, it would more likely comprise the basis of the people’s religion and culture in these three countries. Even in Christianity the concept of God and the mystical dynamic of the religion appeal to Korean thought since they strike a common note with Shamanistic Taoism. It is the peculiar circumstances of Korea that have led to a closer connection and growth of Christianity in Korea than in either China and Japan.

I have hoped to clarify, in this brief sketch, the often misleading impression that Taoism has not been a major element of the Korean religious experience, because it is not immediately noticeable by imposing temple complexes or other monuments. We would do well to direct more attention to cross-cultural influences between religions, rather than to the institutionalized forms, based as they are on more fundamental concerns of all Asian religion: mystical experience, cyclical change, and natural phenomena.

Shamanism lies at the heart of Sun Myung Moon’s church, even if it uses a Christian signboard.

Ancestor liberation, bowing to pig’s heads and marriages between dead people and the living are some examples.

Sun Myung Moon – Emperor, and God

Sun Myung Moon copied the Enthronement Hall of the Korean emperor. The sun and moon motifs symbolize his power over all people and the elements. The spirits of significant historical figures, including military leaders, in Korea and ‘providential’ nations were liberated to mobilize them for Moon’s purposes. This is a Korean shaman tactic.

The shamanic ‘Holy Grounds’ of Reverend Moon

Sun Myung Moon made 120 ‘Holy Grounds’ around the world to connect those nations to the shamanic powers of the Korean Guardians of the Five Directions.

Hananim and other Spirits in Korean Shamanism

an extract from the book, Korea: a religious history by Professor James Huntley Grayson

The Moons’ God is not the God of Judeo-Christianity

In Korean 天地人 ‘Cheon-Ji-In’ means the god of 天 heaven, 地 earth, and 人 humanity in the traditional beliefs, or shamanism, of Korea.

Moon’s theology for his pikareum sex rituals with all the 36 wives

How “God’s Day” was established on January 1, 1968

Soon-ae Hong, the mother of Hak Ja Han

The mother of Hak Ja Han Moon was in a sex cult. In 1957, after she joined Moon’s church, she together with another woman were jailed for beating a mentally-ill boy to remove evil spirits. They killed the boy.

Black Heung Jin Nim – Violence in the Moon church

Black Heung Jin Nim was the name given to Cleopas Kundiona from Zimbabwe. He claimed to be the embodiment of Moon’s son who had died in a car crash. Reverend Sun Myung Moon approved him as his son, but there was a lot of violence in the Unification Church before Moon sent Cleopas home. In Zimbabwe he set himself up as a messiah and abused UC members who had not been warned of his dangerous behavior.