The Pittsburgh Press

Tuesday, May 31, 1977 page 13

Lonely, Barbara Underwood was easy prey for the ‘Moonies’

‘The Moonstruck Cult’ (This is the first in a four-part series describing a young woman’s experience as a disciple of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon.)

▲ Barbara Underwood spent four years as a Moon disciple.

By Bill Keller

TUCSON, Ariz. — Sometime around 1960 the followers of a then little-known Korean “messiah” began moving into a big old house on 21st Avenue in Portland, Ore.

At night the disciples’ songs, some of them in Korean, would carry across an alley and into the bedroom window of a colonial house next door, where a young girl listened as she drifted off to sleep.

They were neighbors on 21st Avenue – the early followers of the Rev Sun Myung Moon and the upper-middle-class Quaker family next door. They had little to do with each other then. But 15 years later their lives would be knit in an emotional and legal tangle of national significance.

The family was named Underwood, and their daughter Barbara, now 25, is a central figure in a drama of alleged brainwashing and exploitation.

Barbara Underwood was swept up four years ago in the Moonies, the best known of the scores of religious cults that have become a growth industry and a legal dilemma during the past decade, touching thousands of American families.

For the Underwoods, the drama climaxed earlier this year in a San Francisco courtroom where lawyers and psychologists argued for 12 days over who controlled Barbara Underwood’s mind.

It began much more peaceably, in October, 1972, when Barbara was a student at the University of California’s experimental campus near the surfing community of Santa Cruz.

Barbara was the sort of student Cal Santa Cruz was designed for: bright, independent, creative, adventuresome, idealistic.

A top graduate of a Portland area high school in 1970, she was a promising poet and photographer with a history of social concerns ranging from an anti-poverty march in Washington, D.C., to the oil spill beach cleanup at Santa Barbara, Calif.

At Santa Cruz she studied sociology and experimented with drugs, Marxism and communal living, always keeping long, thoughtful journals of her experiences.

Barbara’s first contact with Moon’s teachings was not through the Unification Church, but with one of its many operational guises.

More than 60 organizations have been identified by reporters and Moon critics as “fronts” for the church, including names like Creative Community Project, New Education Development Systems. World Family Movement, Center for Ethical Management and Planning, Collegiate Association for the Research of Principles (CARP).

Later, as a Moonie, Barbara would learn to play down or flatly deny any affiliation with the Unification Church when she was “witnessing” on street corners or San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit trains. She would joke about the vaguely academic-sounding front names and help make up new ones.

This deceptiveness is Exhibit A in the case Moon critics make that the church is different from “bona fide” religions.

“Unification Church is a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” Barbara said recently in a four-hour interview at a cultist “rehabilitation center” on the outskirts of Tucson. “There’s definitely a front stage and a backstage, and at least in Oakland (Calif.) the front stage is called any other name but the Unification Church.

“I met a group called the International Re-education Foundation.”

A former college roommate named Joy was living in Oakland in one of several San Francisco Bay Area houses populated by Moonie “families.”

Barbara went to visit her old friend “on impulse” one Friday night in October and found herself overwhelmed by the interest and affection “the family” seemed to feel for her.

Saturday morning she asked them to drop her off at the Oakland bus depot for her return to Santa Cruz. Instead, they turned north on the freeway and headed toward International Ideal City Ranch in Boonville, a Moonie retreat in northern California.

Barbara started to object, then went along: “Inside, I figured: ‘Well, I guess a decision has been made for me.’ ”

The unannounced detour, she would learn, was nothing unusual.

“If you’re in the church, you assume you know what’s best for a person,’’ Barbara said recently. “I know people who were tied up and brought back to the church, and taken places against their will. And other people who had all their things packed for them without their knowing it and moved into the church.”

On the road to Boonville and throughout the weekend, she was pressed to join in religious and folk singing. Two Moonie women were assigned to escort her, and they kept her company around the clock, steering her away from other newcomers.

She received a diluted dose of Unification Church doctrine — introductory lectures called “principles of education” — but there was no mention of Moon or of his ultimate message: that a Korean messiah is coming to overthrow communism in the world.

Four months after Barbara Underwood’s first encounter with the followers of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, the cult beckoned again. This time she was ready.

Ex-cultists and psychologists say such groups tend to attract people at vulnerable periods in their lives – moments of need or insecurity.

Since her October introduction to the Moonies, both of Barbara’s grandmothers had died and she had begun having scary thoughts about death. She had suffered through an unsuccessful love affair. She had had a “mystical-spiritual” experience at the mountain retreat that gave her a sudden new interest in religion.

And she was lonely. In her junior year of college, her greatest objection to the ruggedly individualistic campus at Santa Cruz was that people seemed “rootless; everyone kind of fleets through your life.”

She made a second trip to the International Ideal City Ranch, this time plunging into the vaguely identified group with both feet.

After a visit home to Portland and a trip to Santa Cruz to arrange a leave of absence from school, she moved in with the Moonie “family” in Oakland.

Barbara told her parents she wanted to live with the sect for a few months and write her senior thesis about this seemingly Utopian community. But within a week she was part of her subject.

For the next four years she would sleep on floors or in vans, observe strict cult rules against drinking, drugs and sex, and devote 18 to 20 hours a day to collecting money and new believers for Sun Myung Moon.

The process Barbara went through in her first weeks is described by church members as religious conversion. It has been described by parents, ex-Moonies and some psychologists as “mind control,” “coercive persuasion” or in popular terminology, brainwashing

At first, Barbara said, it was easy to suspend doubt. “There’s not that much you can disagree with.” The lectures were “about love and truth and beauty and goodness and becoming a more giving person.”

Eventually, the Moonies are told that doubt must not be simply put off, but permanently erased. “If you really doubt, you’re considered an insincere person, an untrustworthy person.”

The newcomers are reminded constantly that the world “outside” is an imperfect place. They recall the hassles they left behind – magnified in the lectures and in group “sharing” sessions – and compare that life to the surge of love and warmth in their new setting.

Soon many of them accept the idea that this group is alone against the evils of the world.

“Suddenly there’s an overwhelming desire to repent for your life, get rid of it, confess all the evils that you’ve done,” said Barbara. “Pretty soon you’ve thrown out everything that was of any value in your life before. There comes a point when you have to feel even your parents have this small, possessive love for you.”

The Rev. Kent Burtner, a Catholic campus priest at the University of Oregon who has studied the Moonies and assisted in several “deprogrammings,” believes the critical point for new cult members comes when they learn to feel guilt and shame – not just for their conscious actions, but for feelings and emotions.

“If you can get that by somebody,” says Father Burtner, “you can get them to feel guilty for anything. If you’re hungry or tired or afraid, these are signs of moral weakness. Then the way to assuage the guilt is to do what Moon tells you.

“It becomes a really marvelous way of controlling people.”

Barbara said: “After 18 hours of fund-raising, you’re hungry and you start thinking about a candy bar – that’s selfish. You should be more sacrificial.”

“It was seen as a sign of weakness to want to go home, because you were attached to your parents.”

The greatest guilt, of course, was attached to the ultimate sin: leaving.

“There’s a real instilling of fear that if you leave, Satan’s going to consume you, you’re going to die spiritually, it’s going to be the end of all hope in your life,” she said.

After the first few weeks, sacrifice becomes the life style: long days of work without pay, nights of three to five hours sleep, fasting, denial of physical pleasures.

Devotees even sacrifice to Moon their right to select a husband or wife. When they become eligible for marriage, after spending three years in the church and converting the required number of “spiritual children,” the church may arrange a marriage, possibly with a total stranger.

As Barbara was absorbed into the church, her family reacted at first with misgivings, then alarm.

After a phone call from Barbara a few weeks after her induction, her mother, Mary Betty Underwood, scribbled in her own journal: “Her voice sounds strange, flat and hoarse; she says it’s because ‘we sing so much.’”

Four months later, Barbara visited Portland. Her brother Doug picked her up at the airport, where he found her staring out a window, singing out loud to herself. The family said her voice was worn and sing-songy, her eyes lifeless. She would talk of nothing but Moon’s teachings.

“It’s like she’d parked her brains at the door,” said her father, Ray Underwood, now chief counsel for the Oregon Department of Justice.

In October, 1973, Mrs Underwood and son Phil visited Barbara’s group in Oakland, one of several efforts the Underwoods made to comprehend their daughter’s new way of life.

They were repelled, Mrs. Underwood said, by the occasional violence of the church’s rhetoric. They heard one lecturer tell the disciples to “explode the country. Everybody will be hit by us. We can steamroll the world with love.”

As they prepared to leave, a number of Moonies encircled Phil and insistently urged him to stay. And Mrs. Underwood wrote: “Beneath the cordiality, I sensed something harshly different.”

The Pittsburgh Press

Wednesday, June 1, 1977 page 31

Disciples Fill Moon’s Pockets

‘The Moonstruck Cult’ (This is the second in a four-part series describing a young woman’s experience as a disciple of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon.)

▲ Foes of Sun Myung Moon scrawled “Hitler” on posters heralding Moon’s Bicentennial festival at Yankee Stadium.

By Bill Keller

Tucson, Arizona – “I have established the record in using people, pushing them ahead,” self-proclaimed prophet Sun Myung Moon boasts in Master Speaks, a series of lectures to his advanced followers.

During her four years in Moon’s Unification Church, Barbara Underwood was used to raise a quarter of a million dollars for the Korean evangelist, according to estimates by ex-Moonies.

The 25-year-old Portland, Oregon woman earned the money selling roses 18 to 20 hours a day on street corners, in factories, office buildings and bars.

As often as not, Miss Underwood said in a recent interview here, she and her fellow Moonies lied to customers about where the money was going, a practice church members referred to as “heavenly deceit.”

Based on similar allegations, the Oregon Consumer Protection Division is looking into alleged fraudulent sales practices by Moonies in Oregon. One former high-ranking church member estimates the take from candy and flower sales in Oregon alone is about $10,000 a week.

Barbara’s earnings became part of a tax-exempt flood of money Rev. Moon has used – according to ex-Moonies and congressional testimony – to build a diversified business empire, to acquire extensive property holdings, and to advance his religious and political cause – the simultaneous advancement of South Korea and himself.

According to Barbara Underwood, making money and recruiting new members were the daily obsessions of the church. Conventional religious study was secondary, and the practice of “good works” was almost unheard of.

The church devotion to fund-raising was evident even in the morning chants which started off a typical day in a Moonie house. Rising before dawn, the Moonies would pray in the name of the True Parents – Moon and has wife – read from the Bible, then gather to chant verses like these:

“Glory to heaven, Peace on earth, restore the material foundation” (the church bank account).

“Glory to heaven, peace on earth, find a millionaire to move into the family.”

After a brief stint as a typist for the Forest Service – during which she signed over her paychecks to the church – Barbara was assigned to a seven-member flower-selling team and began a series of sales sprees that would keep her on the road or most of four years.

The teams roamed the country in vans and slept in them at night, even when the weather dropped, as it did one winter in Michigan, to 40 below zero.

“Occasionally, if we thought the flowers would freeze, we would rent a motel room for the sake of the flowers,” she said.

They ate two meals a day, emphasis on starch, sometimes begging donuts or a pizza from passers-by to save their flower-selling money for the church. Sometimes they fasted.

They snuck showers in motel rooms, darting in after the paying tenants had left and before the maids arrived to clean up.

The Moonies would work taverns until closing time, finding drunks the most pliable customers. Then they would clean and cut the flowers, put them in water, and bundle up for a few hours of sleep.

“Our bar runs would be flowers that were dead from two days before,” when the flowers had been air-freighted in from San Francisco, Barbara said, “We’d just wrap them up in green paper and disguise them and sell them.

“The new people who had just started selling, it was so hard for them to sell dead flowers; it would really hit their conscience. But eventually you had to indoctrinate them to feel the higher purpose, the spiritual purpose.”

Customers who asked were told the money went to benefit something called New Education Development or another front, which Moonies would variously describe as a Christian youth group, or a nondenominational religious community, or a drug abuse program.

“The whole justification is that you have to get money from everybody, because that might be their own ticket to heaven,” said Barbara.

Barbara Underwood became an assistant leader, and finally the leader, of a seven-member flower team and was trusted to establish a sales base in Toronto.

In Canada, she got an importer’s license, opened a bank account and rented vehicles using a phony address and pretending to be a Canadian citizen, in apparent violation of Canadian immigration laws.

“We were going by divine law,” she explained. “We weren’t going by secular law, democratic law.”

Barbara’s journal includes her own list of 18 ways the Moonies routinely broke the law, including soliciting without permits and in forbidden areas, driving uninsured vans, giving false information on welfare and medical aid applications, ignoring traffic tickets and failing to file traffic accident reports.

“We were in a lot of car accidents because people were so tired driving,” she said. “One car was totaled. It was always because somebody fell asleep.”

Once Barbara’s flower team took a sick team member to a hospital emergency ward and got her treated as an indigent, although they had $7,000 in their van, Barbara said.

Barbara and other former members of her flower-selling team estimate they averaged about $2,000 a day. A top seller, Barbara regularly collected $400 herself.

“I know I made significantly more than my dad as a lawyer,” she said. “But I never felt I was doing enough.”

Despite the hardships, Barbara says she liked the excitement of being on the road, and preferred the relative independence to living in a Moonie house all the time.

Flower-selling is the most common Moonie money-maker. But Moon’s international business empire includes companies marketing pharmaceuticals, stoneware and titanium, karate schools, restaurants and a variety of publications.

Moon’s business activities in the United States benefit from large amounts of free labor.

Phil Greek, a 22-year-old who recently left the Moonies to continue an interrupted education at Stanford University, started one lucrative enterprise in Chicago — selling butterfly displays encased in plexiglass.

Greek said he made as much as $800 a day selling the displays for $15 to $20 in Chicago office buildings.

Jeff Scales, who was Barbara Underwood’s flower team leader until he left the church last December, ran several Moonie businesses in the San Francisco Bay area. He dreamed up others which never got off the ground – the weirdest one, in 1969, a proposal to export Frisbees to Spain.

Scales ran a chain of restaurants, caterers and tea and coffee shops under the trade name “Aladdin.” He also oversaw a maintenance and carpet-cleaning company.

“With no labor costs and people willing to work 14 to 15 hours a day, you can undercut anybody,” he said.

Scales said that when he ran the Aladdin restaurants, employees signed over their pay-checks to the personal slush fund of West Coast church leader Onni Durst, who spent freely on clothing and jewelry for herself.

The Moonies also made feeble efforts to fulfill their prayer to “find a millionaire to move into the family.”

In one case described by Barbara and ex-Moonie Eve Eden, two attractive Moonie women wooed a rich Jewish hotel owner in California, establishing a new front – Judaism in Service to the World – in hopes of attracting some of his wealth.

The women played up to him – bending, but apparently not breaking, the strict church rule of chastity. The man loaned them the key to his penthouse, bought them presents, but never blessed the church, the ex-Moonies said.

Because Rev. Moon’s sect has the legal protections and tax-exempt status of a religion, little is known with certainty about how much money the church raises and where it goes.

Large sums have gone to acquire property in New York (Rev. Moon once bid to buy the Empire State Building) and in other cities. Some has gone to a slick, new color newspaper, The News World, which is distributed widely in Washington and New York.

More money has been poured into Rev. Moon’s religious and political rallies, including a Bicentennial fireworks display at the Washington Monument and several demonstrations supporting the war in Vietnam and then-President Richard Nixon.

In sworn testimony last year before the House international organizations subcommittee, witnesses alleged Rev. Moon has supported lobbying efforts on Capitol Hill in support of the government of South Korea, which the Unification Church teaches is the new holy land.

The witnesses also alleged – and the subcommittee ls still investigating – operational ties between the church and the Korean Central Intelligence Agency.

Rev. Moon himself boasted in a lecture to top church leaders three years ago that “we have successfully dealt with many senators and congressmen,” and that “every politician in America has to think twice about the Rev. Moon.”

The Pittsburgh Press

Thursday, June 2, 1977 page 33

Moonie Court Battle: Fighting For ‘Rights’

‘The Moonstruck Cult’ (This is the third in a four-part series describing a young woman’s experience as a disciple of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon.)

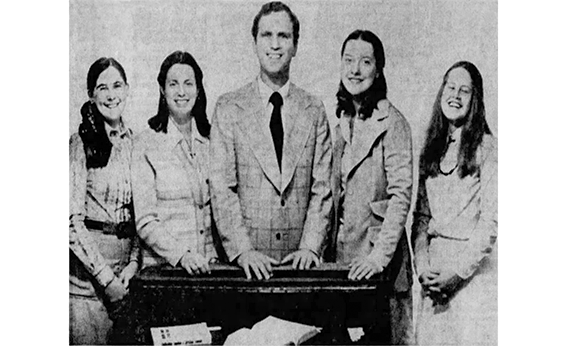

▲ From left, Barbara Underwood, Janice Kaplan, John Hovard, Leslie Brown and Jacqueline Katz.

By Bill Keller

Portland, Oregon – By the summer of 1976, Ray and Mary Betty Underwood were almost resigned to the idea that their 25-year-old daughter, Barbara, had traded them in for the mysterious family of Rev. Sun Myung Moon.

The Underwoods are Quakers and political liberals (Ray Underwood quit a job with Sen. Mark Hatfield, R-Oregon, when the senator endorsed Richard Nixon) so they found Moon’s warlike talk of world conquest distressing.

But they are also long time members of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), with no-compromise views on religious and political freedom. So they felt bound to honor their daughter’s choice.

Last March, though, the Underwoods entered a San Francisco court room to battle the Unification Church, their daughter, and the ACLU in a case lawyers believe will break new constitutional ground.

The case pitted the American guarantee of freedom of religion against an unproven and psychological concept, freedom of thought.

The Underwoods had decided that their daughter had joined the Unification Church under severe emotional pressure and, though not physically restrained, was powerless to leave it without help.

Together with parents of four other Moonies – all over the age of 21 – the Underwoods asked the courts for 30 days in which they and professional deprogrammers would try to “restore the children’s ability to think for themselves.”

“While it seems extreme to say it, these young people are put into a form of slavery, mental enslavement.” Underwood, who is chief counsel for the Oregon Department of Justice, said recently.

Once they are in it, the pattern is to keep them so busy, so preoccupied, that they never have an opportunity to stand back free of the influence of the cult…

“I don’t see how there’s any great threat to civil liberties, as long as the deprogramming is conducted under court supervision. It’s a special situation that ordinary principles of free choice don’t apply to, because these people aren’t free.”

Underwood argued, too, that Unification Church is legally different from other religions because it recruits members without telling them it is a religion. Barbara, for instance, joined what she thought was a communal group called International Re-education Foundation, and didn’t hear Moon’s name until she had been swept up in the movement.

“I know of no legitimate church that brings in its members on the basis of lies,” Underwood said.

The church counter-punched with charges ranging from religious persecution to the allegation that deprogramming was “the real brainwashing.”

The five Moonies, with Barbara as the star witness, testified they had converted freely and were blissfully happy in the church.

The ACLU called the parents lawsuit an attack on freedoms of religion and association – in short, a threat to a person’s right to be different.

“To deprive people of their liberty because their parents don’t agree with their religious beliefs is blatantly unconstitutional,” ACLU attorney David Fishlow said. Fishlow said the legal danger in the case was not brainwashing, but overprotective parents.

“Barbara Underwood is a very intelligent, thoughtful person who probably made a mistake when she joined the Unification Church. But I have no doubt the time would have come when she would have decided to leave on her own,” Fishlow said.

He contended that any group puts peer pressure on members to stay in, “but that doesn’t mean you’re a zombie – I don’t believe in witchcraft, and I don’t believe in mind control.”

The Underwoods say they didn’t either, not seriously, until they began meeting last September with a group of parents whose children had joined cults.

Adrian Greek, retired director of adult education for the Portland YMCA, and his wife, Ann, began organizing parents of cultists after two of their children became Moonies. They say their group, Concerned Parents, knows of about 15 Portland-area families touched by Moon’s movement and has put some of them in touch with lawyers and deprogrammers.

In a series of meetings in Portland, the Underwoods first heard the “mind control” theories of psychologists Robert Jay Lifton of Yale and Margaret Singer of the University of California, who had pointed out similarities between cult followers and former prisoners of war in Korea and China.

The Underwoods also learned that parents in California had begun winning court-ordered conservatorships for their cultist children “ex parte” (without bringing their children or church into court).

The conservatorships – called guardianships under Oregon law – were designed to protect the senile or mentally incompetent who cannot care for themselves or who might be pray to swindlers.

Last December, the Greeks won a temporary guardianship over their 22-year-old son, Phil, in Marion County, the first Moonie case in Oregon. They later obtained a California custody order over their 21-year-old Moonie daughter, Cheryl, but she fled the state.

Just before Christmas, the Underwoods determination was bolstered by a phone call from Eve Eden and Jeff Scales, two of Barb’s closest friends in the church. They had been yanked from the cult under conservatorship and said they wanted to help get Barb out, too.

Assisted by attorneys from the Freedom of Thought Foundation, an anti-cult organization in Tucson, Arizona, the Underwoods obtained a Californian court order for their daughter’s custody. But it was too late.

“There where conservatorships out and nobody knew who for, so we were being extra cautious,” Barb said. She said Moonies leaving their houses were told to wear garbage bag masks so they could not be identified by scouts for the parents.

On January 5, Barb and 16 other Moonies were told by church leaders to sign papers authorizing unnamed attorneys to represent them. Then a jump ahead of the conservatorship, they fled the state.

A month later, Unification Church lawyers agreed to return a group of Moonies to California on one condition: the parents would have to fight it out in open court.” The Underwoods and four other parents agreed.

Church leaders summoned Barbara from a flower-selling mission in New Mexico, and gave her $20 “escape money” in case she wanted to flee from deprogrammers after the court verdict.

“We were really prepared, if we lost the case, not to see Barb again,” her mother said.

The case of Underwood vs. Unification Church lasted 12 days. A parade of parents, Moonies and psychologists debated whether the Faithful Five, as the Moonie defendants called themselves, were converts or robots.

Stanford psychiatrist Samuel G. Benson and Dr. Singer, testifying for the parents, described the Moonies as childlike and emotionally frozen, limited in their mental range and vocabulary and out of touch with world events.

“Benson said Barbara finished answers about Barb” her mother wrote afterwards. “I don’t know how she felt, but I was worried to death.”

Dr. Singer who has studied more than 100 ex-Moonies, said the church practices classic tactics of “coercive persuasion,” described by Korean prisoners of war: physical and social isolation, sleep deprivation, complete monopolization of time, a heavy emphasis on guilt, strong group pressure, repetitive indoctrination lectures and hypnotic chanting.

The Moonies, she said, were not even aware they had joined a religion until the indoctrination was complete.

Recently, Dr. Singer compared the transformation of Barbara Underwood to that of Patricia Hearst at the hands of the Symbionese Liberation Army. The psychologist, who has interviewed both women at length, said Barbara “was a quite scholarly woman who dropped her whole past, and would answer simple questions by parroting abstract phrases from Unification Church doctrine.”

Witnesses and lawyers for the defense countered that coercion could not take place without captivity, hypnosis or drugs; as long as the Moonies were physically free to leave, their liberty had not been violated.

The alleged brainwashing, they said, was little different from the persuasion practiced by other religions – or even by political and fraternal groups, businesses and advertisers.

Los Angeles psychologist Alan Gerson and Washington psychiatrist Harold Kaufman tested the defendants and found them normal, healthy, mature, creative and happy.

The Moonies, church attorney Ralph Baker said, “had a real conversion. They stopped using narcotics, stopped living with other people and straightened out their morals. That’s what America needs.

“Their parents had 18 years to work with them. Now they’re saying let’s get them back to their natural selfish state so they can start smoking and using drugs and living with people.”

Outside the courtroom, Barbara stayed with the Moonies, but joined her parents most days for lunch or dinner. Her parents hopes would soar at one meal as Barbara showed clues of her old independence, then sink at the next meeting when she was adamant about returning to the church

Considered the most articulate of the defendants, Barbara went before reporters repeatedly as spokeswoman for the Faithful Five.

With her parents sitting a few feet away, Barbara took the stand and said her time in the Unification Church had been “as real as I’ve ever known happiness.”

Insisting she had joined the church freely and stayed without coercion, she said: “It’s my life to choose the beliefs I follow. I feel if I make a mistake in my life it should be my own choice.”

(In an interview several weeks after the trial, Barbara said her testimony that today was an act: “All of us perjured ourselves on the witness stand during our hearing, because we had to protect the church,” she said.)

On Friday, March 25, Superior Court Judge S. Lee Vavuris handed the Faithful Five over to their parents for 30 days, saying he had decided to put his faith in the family. “We’re talking about the essence of civilization here – mother, father, child … The child is a child even though a parent maybe 90 and the child 60,” he said.

The day of the ruling Barbara let another Moonie – John Hovard, the only defendant still in the church today – handle the press. She said she was secretly relieved and afraid it would show.

“Inside, I was hoping for it. It seems so strange, but I wanted to hear what they had to say and understand whether there was any validity at all to the people who left the church who I trusted, and to my parents viewpoint … and I knew that I would not be allowed to (hear the other side) if the conservatorship were not granted,” Barbara said.

The following Monday, Barbara announced she would leave the church, fire her attorneys and go voluntarily into her parents’ custody.

The Underwoods won the battle, but the war is not over.

The California Court of Appeals has since ruled unanimously that Judge Vavuris’ ruling was dubious law and has issued a stay. After reading the trial transcript, the appeals court is expected to issue a final order in a month or so.

If the court overturns Vavuris’ decision, parents and deprogrammers may have to look for another legal way to attack cults in California, and similar court fights can be expected in other states.

The Pittsburgh Press

Friday, June 3, 1977 page 21

For Moonies ‘Deprogram’ Meant Torture

‘The Moonstruck Cult’ (This is the last in a four-part series)

▲ Those who returned to Rev. Moon’s church after deprogramming were regarded as heroes.

By Bill Keller

Tucson, Arizona – Deprogramming, the psychological antidote to alleged brainwashing by exotic religious cults, has become almost as controversial as the cults themselves.

It is such a chilly, 1984-ish word even those who practice it would rather call it something else.

To a member of Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church, the word conjures up kidnaping, confinement, torture, loss of friends, loss of God, loss of hope.

Barbara Underwood, who was deprogrammed a few weeks ago, now calls the experience “sensitive and compassionate,” and says she may want to try it herself on those still in the church.

But while she was in the Moon movement she was warned that deprogramming tactics might include cursing, beating, humiliation, seduction or even rape.

A few months ago she was secretly spirited out of California to avoid deprogramming. Another time she went, armed with chemical mace and a deafening noisemaker, to stake out a house in Ohio where a Moonie was undergoing deprogramming and, if possible, aid in an escape.

So intense was the terror of deprogramming inside the cult, she said, that some Moonie leaders passed out razor blades, with instructions that captured Moonies should attack their deprogrammers or hurt themselves so they would have to be taken to a hospital.

The horror stories of deprogramming, ex-Moonies claim, are largely church propaganda fed by reports from disciples who have been partway through the process and escaped back to the church. Ex-Moonies say the escapees embellish their stories to enlarge their hero-status within the cult.

One recent escapee from deprogramming has claimed his captors poured water up his nose; witnesses who were present say one of the deprogrammers sprinkled water in his face in an effort to break his trance-like state. Another Moonie says she was beaten with pillows; witnesses say an ex-Moonie gently tossed a pillow at her to get her attention.

Ex-Moonies don’t deny that occasionally a cultist has been slapped or sworn at, or that it has sometimes taken considerable force to hold a deprogrammee — especially in cases where the youngsters have been snatched without the authority of a court order. But they maintain such instances are exceptional.

Berkeley psychologist Dr. Margaret Singer, who has studied more than 100 former members of the Unification Church, said she knows of “nothing untoward” about the deprogrammings of any of Moonies.

Dr. Singer says that almost all the ex-cultists she studied continued to be deeply religious, either returning to the faith of their childhood or developing “a basic religious belief of a kind they say is really theirs.” Barbara said she has kept a deep faith in God, without feeling attached to any particular religion.

But concern about deprogramming is not limited to Moonies, nor based entirely on exaggerated stories of brutality.

Ralph Baker, attorney for the Unification Church, said he believes the pillow-beating and water-up-the-nose stories but feels even nonviolent deprogramming “is kind of alien to our American way.”

Baker says deprogrammers often charge “$15,000 to $25,000 a head,” and are simply profiteers taking advantage of gullible parents.

Deprogramming is expensive, though less so than Baker claims. The Freedom of Thought Foundation in Tucson, which wrestled Barbara from the Moonies says it charges parents a $10,000 retainer for legal work, travel, motels and the actual deprogramming. The foundation also provides several weeks of “rehabilitation” in a bungalow on the outskirts of Tucson, paid for by a Detroit philanthropist whose daughter left a cult.

Ann and Adrian Greek, a Portland, Oregon couple whose son, Phil, was pulled from the Unification Church under an Oregon court order and deprogrammed in the state, said it cost them about $4,000. Neither family complained of the cost.

According to Barbara and several other former Moonies, the deprogramming process consists of two basic elements: confinement and conversion.

After the “pick-up” of a Moonie, sometimes a forceful kidnaping but now more commonly under a court-ordered conservatorship, the cult member is confined in a motel room, at least until he or she seems unlikely to attempt escape.

The deprogramming period, usually a matter of days, often includes walks and trips to restaurants. In the case of Barbara who responded rapidly, the first few days included a picnic, horse-back riding and a tour of a California winery.

All of those interviewed said the cultists are given three meals a day and at least 8 hours of sleep a day. Under the conditions of Barbara’s court order, she was allowed to talk to her church attorney, to have any reading material she wanted and to practice her religion.

“I’d rather talk to you well rested, well fed and with all your faculties,” said Joe Alexander, a veteran deprogrammer with the Freedom of Thought Foundation. “You can accept what I have to say much better.”

Alexander, a high-school-educated former Ohioan who used to run a chrome and nickel plating shop in Akron, got into deprogramming six years ago when he helped pull his nephew out of a small cult called The Christian Foundation.

He claims a 90 per cent success rate, working with hundreds of young people in more than 30 cults. The Moonies, Children of God, the Hare Krishnas, Divine Light Mission, Scientology, The Christ Family, The Way International – “All of the groups are carbon copies of each other,” he said.

The key figures in a deprogramming are not usually the professionals like Alexander, however, but ex-members of the cult who are fluent in the church jargon and can reassure the “client” that they’ve been through it themselves.

The goal ls to get the cultist to listen.

“Eventually each person deprograms himself,” Barbara said. “Eventually a person talks out all the defenses until they’re tired of talking out their defenses, and then they begun to listen.”

The process was easier for Barbara than for most. She says her faith in the church had already been rattled when her two closest friends – Eve Eden and Jeff Scales – were taken and deprogrammed last December. Both now practice deprogramming.

Then during the 12-day courtroom fight for her custody, Barbara said, the give and take aroused her curiosity. Why, she puzzled in her journal, had her attorneys not tried to convince the court of the alleged abuses that take place in deprogramming? And if all those charges were true, she wondered, why would her parents be willing to put her through it?

When the judge awarded her parents a 30-day conservatorship, Barbara and four Moonie co-defendants were driven to the Travelodge near San Francisco Airport, where they were met by a large team of deprogrammers and ex-Moonies.

The families split up into smaller groups, Barbara with her parents, her old friends Jeff and Eve, and Gary Scharff, once the top East Coast lecturer for Moon, now an official of the Freedom of Thought Foundation.

Many cultists resist for days, chanting to themselves, praying, pacing the room. Eve Eden said she “tried to fake it” for four days; pretending the talk was sinking in but actually chanting inside and concentrating on the possibility of escape. Barbara, however, had decided from the start to give it a try.

“I really had confidence that if I talked, it wouldn’t shake my beliefs,” she said. “I’d spent four years believing it and I’d sacrificed my whole life for it, 20 hours a day working for it and four hours dreaming about it.

“I just couldn’t conceive of anything short of brutality and torture that would get me to change my mind.”

For the past several weeks, Barbara has been relaxing in Tucson with other ex-Moonies; swimming and hiking, reading and studying, “trying to reclaim my past.”

Her future plans are uncertain, which is not unusual. Dr. Singer says it takes most Moonies eight months to a year to return to a “normal” way of life.

“Once you’re deprogrammed, that’s one thing,” says Eve Eden. “Then you’ve got to face yourself.”

In New York recently to be interviewed for a television talk show, Barbara worried for a long time whether to wear her long brown hair down, a style considered “satanic” in the church. Concerned about the Moonies who might be watching, she wore it up.

But despite such emotional tugs she feels she is free of the Unification Church, and glad of it.

“I can’t express the amount of relief I feel about being rescued,” she said. “And I really feel it was a rescue, because I know that I never would have left on my own. It would have been absolutely impossible. It’s so hard for anybody outside of the experience to understand the depth of that.”

HOSTAGE TO HEAVEN

by Barbara Underwood and Betty Underwood

Four years in the Unification Church by an Ex Moonie and the mother who fought to free her.

published 1979

back cover

A riveting firsthand account by a mother and daughter of the dangers of cult life, and a moving testimonial to the power of family love.

From the advance praise:

HOSTAGE TO HEAVEN is the mother-daughter book of the year—in poignancy to be compared with Anyone’s Daughter by Shana Alexander. … An exceedingly personal book, it will also be grist for psychologists and for social commentators on our times. Once you start reading this alarming work you cannot put it down.

Paul Ramsey, Professor of Religion,

Princeton University

A moving and gripping account of a young woman’s journey to define meaning and structure in her life, and in the universe, but at the expense of her individual and intellectual freedom … This is an autobiography of searching, of endurance, and of familial love of the highest order. It is an enlightened warning to each and every household.

Senator Mark O. Hatfield, Oregon

Not only is the book informative and revealing about what led to the daughter’s becoming involved with the Moonies and what happened while she was with them, both to her and her family, but parts of it hold the suspense of a mystery novel.

Margaret Thaler Singer, Professor of Psychology,

University of California, San Francisco and Berkeley

cover flaps

HOSTAGE TO HEAVEN

by Barbara Underwood and Betty Underwood

Four years in the Unification Church by an Ex Moonie and the mother who fought to free her

A deeply disturbing look at the dangers of cult life, and a testimonial to the power of family love

Betty Underwood and her daughter, Barbara, give their overlapping, sometimes conflicting versions of the four years Barbara spent in the Unification Church, more popularly known as the Moonies: four years of increasing anxiety and anguish for Barb’s family, four years of self-denial, self-sacrifice, work to the point of physical and emotional exhaustion, and the excitement that comes from a sense of mission and destiny for Barb.

What Barbara saw as her God-given purpose in life—fund-raising, recruiting, and, on occasion, much more dangerous and frightening work for the benefit of the Moonies— Barbara’s parents came to see as enslavement. And when a group of parents similarly deprived of their children by the Unification Church approached them about their possible interest in springing Barb from the Moonies, they began an intense period of soul-searching. They were torn between their desire to respect their daughter, her integrity, her civil rights, her freedom to make her own decisions on the one hand, and, on the other, their growing conviction that she had endured a form of brainwashing that effectively prevented her from making any free choices.

What followed was the internationally publicized court hearing of the “Oakland Faithful Five,” where, for the first time outside of the context of war, mind control was the central issue in a court of law. Climaxing in a series of courtroom scenes in which Moonies and their parents confront each other. Hostage to Heaven is a dramatic and moving portrait of a family in conflict. As an indirect testimonial to the strengths and virtues of the traditional family, as a deeply disturbing account of the emotional and psychological chaos in which so many of our young people are floundering, and as a horrifying look at the power that various cults can exercise over them. Hostage to Heaven is an important story, the ramifications of which are being played out on the front pages of newspapers across the nation.

Barbara Underwood was born in Eugene, Oregon. After spending four years in the Moonies, she attended the University of California at Berkeley and received a B.A. degree in sociology in June 1979. Since she left the Moonies, she has done deprogramming and counseling with other young people from various cults, and at present is working free lance as both writer and counselor. Recently she married Gary Scharff.

Betty Underwood is an award-winning author of books for children and young adults, whose book The Tamarack Tree received the Jane Addams Children’s Book Award for excellence in writing on the theme of brotherhood. She was born in Rockford, Illinois, and lives in Portland with her husband, Ray. She is the mother of three children.

Acknowledgments

Ray Underwood’s insights, steadiness and fortitude helped build this book.

Gary Scharff added a very special dimension of care and understanding.

Clarence, Scott, and Lauriel Anderson gave of themselves in time of need, as did Russell, Douglas, and Jeffrey Underwood.

Carl Katz generously let us share some of his notes on certain days of the court hearing.

Eve Eden and Jeff Scales were initiators and counselors.

Jean Naggar and Beth Rashbaum believed in the book.

Contents

Foreword by Barbara Underwood ix

Foreword by Betty Underwood xi

Barb: Who Is the Captive? 1

Betty: Growing Up—Barb, Her Family, Their World 13

Betty and Barb: Going Into the Cult—A Combined Account 37

Barb: In the Unification Church—I Am Reborn 57

Life at the Centers 61

Flower Seller 75

Behind Fences: Boonville 97

All for True Parents: National Activities 109

Who Is Not With Us Is Against Us: Persecution 121

Betty: In the Cult—Visits and Nonvisits 127

Betty: Deciding to Take Action 151

Betty: Hearing 163

Barb: Hearing 213

Barb: Deprogramming 233

Betty: Barb’s Coming Out 257

Barb: Free of Captivity 263

Betty: Barb Is Out 271

Barb: Conclusion 277

Appendix:

Mind Control 283

The Sociology of Cults 289

Unification History 291

Unification Politics and Finances 293

The Divine Principle 297

Glossary 299

Foreword by Barbara Underwood

The genesis of my voice in this two-person account goes back to April 1973, before I entered the Unification Church. As a student of sociology at the University of California at Santa Cruz, I had intended to keep an objective account of my experiences while “studying” the Unified Family. But I never predicted an account of four years duration. Nor did I predict such a totally involving and personal record. In short, I failed to anticipate the overwhelmingly seductive power of an experience to which I eventually surrendered without reservation.

I waged an inner battle about keeping my journal while I was in the Church. At first writing seemed like a personal, selfish attachment. So I stopped. Then I conceived of my writing as a testament by a living disciple of the Messiah; I thought my journals might one day be a chapter in the “Completed Testament.” I also began to cherish my Church brothers and sisters whose personalities and character traits I felt compelled to preserve, with the intention of writing a series of biographical sketches some day when there was time—presumably when the Kingdom of Heaven arrived.

After leaving the Church in April 1977, I worked with my mother on an account of the events of the preceding four years, years that had transformed our lives. Our decision to write together, as mother and daughter, reflected a need to bridge the chasm those years had created. As I read her story of the pain of rejected parenthood, my love for her took deeper root. As she read my story of sacrifice and visionary hope, she recognized a reflection of her own youthful idealism.

The Unification experience is complex. Within the Church or without, there are no ultimate victors and no easily defined enemies. And within the Unification membership there are decent but fallible human beings demonstrating a desire to love, to weave myth, to claim for themselves the glory of God. Unfortunately, the passion for God and goodness can lead to severe violations of the freedom of the individual. And worse.

Was I “brainwashed”? My mind was certainly manipulated through my intense desire to believe and love, my freedom was lost, my values distorted. But even now it is difficult to say for sure which cult experiences are dangerous, how to evaluate them, how to strike a balance between spiritual commitments and secular freedoms. Having seen both sides of the issues involved, I have no easy answers.

Foreword by Betty Underwood

“How the Moonie Magic Is Turned On”; “The Battle for Mind Control”; “Out of the Shadow of Moon Madness”; “What that Spaced-Out Look Means”; “Judge Gives Moonies to Parents”…

On and on they went, the lurid yellow journalism headlines about cults and cultists.

When I came from my daughter’s court hearing, the last thing I wanted to do was write a book. I wanted instead to forget.

But after I’d regained my strength, I did put together the notes on the hearing in order to give them to a trusted young journalist friend.

Meanwhile, those sensational headlines kept proliferating and added to my sense that the cult phenomenon was being treated by the media as though it happened only to weird people.

I can’t remember the exact moment when Barb and I came to an agreement to try a book, probably sometime in June 1977, after she had left the cult.

By the fall it had already taken rough-draft shape as Barb clattered upstairs at the typewriter while downstairs in the den I did the same. Every now and then we shouted up the stairway to confirm a point or ask a question.

We were trying to write a book which would say, among other things, that our experiences could happen to any American family.

Look up and down the street (and inside your hearts) and, yes, it could happen.

More by unspoken understanding than by grand design, we began this two-person account, some of it based on journals and tapes that both of us had kept at various times during the four years Barb was in the cult.

A book which we hoped would tell what we knew to be our truth as we understood it.

Barb: Who Is the Captive ?

“And I know not to this day

Whether guest or captive I.”

—SIR WILLIAM WATSON

AUGUST 1976.

“Come immediately to Hearst Street. Pack for a week. You’ve got to look mature, up-to-date. This is a very special mission so I can’t tell you over the phone. They’re probably listening in. All right?” The voice was not waiting for an answer. It had delivered its command.

“Teresa, there’s one thing. My mother’s flown all the way to San Francisco to spend the weekend with me. I haven’t seen her in two years. She’s coming to Washington Street tomorrow morning.”

“Don’t worry about your mother. You can pray for her,” the voice advised, determined and dispassionate.

“Shall I call her tonight?” I asked hesitantly. “What shall I do?”

“No, absolutely don’t call. You’ll have to explain too much. Leave a note at the front desk and someone’ll treat her gently when she arrives tomorrow. Say you’ve been called out of town on an unexpected emergency,” Teresa ordered. “Now come quick. Amos and Irene are waiting.”

I hung the phone up, nervous with the excitement of imminent intrigue. Racing upstairs two at a time, I thought of my sparse wardrobe packed in brown grocery sacks in various closets. I had nothing fashionable to wear, only corduroy pants and turtlenecks, my daily uniform for flower selling or Boonville ranch life. As I rooted around the sisters’ wardrobes, I suddenly felt inadequate, wrongly chosen for the mission. Trying on dress after dress, I appeared to myself too young, too babyfaced, too tomboyish.

All the dresses were too short.

“Oh, no, my poor mom,” I thought abruptly. “She’ll never understand.” But I knew such thoughts were looked on as total faithlessness; I had to extinguish them.

Finished packing, wearing a tailored blue dress a staff sister had lent me, I scribbled a note which read: “Dear mom. I’m sorry I can’t see you. I’ve been called out of town on an emergency because a Family friend of mine needs me. I’ll write you later. Love, Lael (Barb).”

As I was driven across town, guilt was replaced by a secret sense of power which flooded me—after all, I’d been chosen to represent God and the Lord of the Second Advent. I was being given this chance to help establish the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth.

Irene, an elegant, angular-faced Jewish woman from New York with a gutsy, omniscient manner, greeted me at the door of the palatial Hearst Street center. I’d never felt comfortable around her. I’d been in the movement two years longer than she, but she had swiftly ascended to a higher position of responsibility and power. I knew too well about myself what Teresa had once told me, “Your problem is, you came as a wild rose and you’ve never been properly pruned.” Irene was already pruning others.

Amos, tall and restrained, disguising his urchin spirit, waved me a good night as he crawled into his sleeping bag next to the front door to guard the entrance to Hearst Street center. “Heavenly dreams,” he called out in a paternal voice. “Get some sleep. In the morning we’ll tell you what’s about to happen.”

Irene and I marched up the three flights of newly carpeted stairs. We opened our sleeping bags, removed our first layer of clothes, and, in order to execute a quick wake-up in the morning, hopped in, slips, hose, and all. “Let’s pray, then I’ll tell you the plan,” Irene said.

“O.K. You and either Jonah or Amos will be flying to Columbus, Ohio, to try to free Michele Tunis from deprogrammers and bring her back to the Family. We know where they took her after her parents kidnapped her because she left a note with her wallet in the San Francisco airport indicating Phoenix, Arizona. Then two days later she left a message and address in the stall of a john in Illinois; someone mailed it to us. She’s at the Alexanders’ house in Munroe Falls, Ohio, being deprogrammed. Of course, she’s there against her will, and we don’t have much time before they could break her. They could even be torturing her right now. You’re to go along to help influence anybody in the state government or courts, or police departments, to help release her. This is criminal. We’ll talk more in the morning. We only have three hours till we get up. Good night.”

“Amazing,” was all I could answer; my shivering I kept to myself.

“Hurry, Amos,” Irene yelled. “Onni and Abba are expecting us for breakfast by eight!” Onni (meaning “elder sister” in Korean) was the handsome, forbidding spiritual commander of Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church in California. Her will was undisputed, her decisions about policy matters autocratic and final. With her mystically manipulative aura, she was Moon’s most faithful and accomplishment-oriented disciple, was called his “daughter-in-spirit,” and was often bodyguard and caretaker of Hak-Ja Han, Moon’s wife, when she attended special public events in New York and San Francisco. Although everyone worshipped Onni’s passionate and indefatigable ambitions for God, privately she was regarded as impersonal and scary by certain staff members and novitiates alike. Abba (meaning “father” in Korean) was the name Onni had given to Dr. Mose Durst, a kindly, philosophical, tender Jewish college professor whom she’d handpicked as her husband and been married to in a “blessed” service performed by Moon himself. Dr. Durst, a credible public performer, had developed a benign front organization called New Education Development Systems, Inc., whose generalities about love and sharing appealed to and brought in many innocents, who later discovered they had somehow become members of the Unification Church. Together, Onni and Abba formed the leadership of the Moon mission on the West Coast.

We piled into the car. Within minutes, Amos, Irene, and I entered Onni’s magnificent western-style Berkeley Hills mansion, named The Gardens, through a controlled intercom system of electronic gates and doors.

We took off our shoes, stopped for pious and grateful prayers, and looked to each other for further directions. Soon someone beckoned us into the kitchen, where breakfast was being served: pancakes, bagels, yogurt, cheeses, eggs, juice, coffee. Preparations were always dignified and bountiful around the local “true parents.”

Onni came in with a flourish and indicated we should sit. Abba trailed in behind, fatherly, affectionate, with his arm around Jonah, one of the business-brain-children of the church.

I rose to shake hands with Dr. Durst. We all waited to see what kind of mood Onni was in. Our spiritual lives—which is to say everything that mattered to us—depended on pleasing her.

She wore curlers in her striking black, usually stylish hair; she was the least adorned I’d ever seen her. She radiated impatience, anxiety. Dr. Durst, too, looked more than usually upset.

“So, Jonah, you know how to get Michele back?” Onni barked in her idiomatic Korean-American blend.

“Well, we know where she is, but we don’t know who to go to when we get there. Play it by ear, I guess,” Jonah answered.

“You mean you don’t know what to do?” Onni accused. An oppressive silence followed.

“Amos, you go instead. Jonah, you don’t have head for this.” Jonah, shocked and speechless, turned to Dr. Durst for support. But there was no help there, either.

“Amos, you know all legal part? You and Lael make plane reservation right now. Lael, do exactly what Amos says. You must get Michele back. She so stupid to go with her dad. Good luck.” Onni got up and went out of the room.

Dr. Durst seemed near to tears. We knew he, too, saw deprogramming as the violent death that stripping away one’s spiritual life meant to the Church. The end of all hope for Michele … He showed us out the door, offering unspoken encouragement.

Amos and I stood for a moment on the doorstep. We had our orders, but no strategy. We’d have to devise a battle plan, using only God’s intervention and guidance.

At the airport Amos immediately assumed the parental role. From now on, I was to be his “object” and support, his obedient assistant … his attractive child. He purchased the tickets and we boarded the United airliner.

Picking out window seats, Amos motioned me to sit down. He took my hands in his and, as older brother-in-charge, urged, “Let’s pray: Heavenly Father, we’re so sorry for your misery. We know you’ll never have a moment of happiness until our Father has subjugated Satan in the spirit world and started the Kingdom on Earth. We’ll do everything we can to claim our sister, Michele, back from Satan’s grasp.” His beseeching voice concluded, “We pray that you can work through Lael to follow Amos exactly, and that together we can bring victory to our True Parents. Amen.”

It was a long ride. Amos opened his attache case and handed me piles of news articles and leaflets on the recent barrage of kidnappings and deprogrammings by parents of various cult young people, from Unification Church to Hare Krishna to Children of God. To the Church, the real devils appeared to be Ted Patrick, a black man known for his forceful snatches; Joe Alexander, senior and junior, noted for their legally sanctioned deprogrammings; and the Alexanders’ “mercenary” attorney, young Michael Trauscht from Tucson, Arizona. Michele was being held captive by the legal device of a conservatorship her father had just been granted by a California court. Her father had claimed she was in need of temporary parental guardianship because she was susceptible to “artful and designing” people in the ranks of the Unification Church. This was the first I’d ever heard of such a legal tangle; it sounded threatening, and I agreed with Amos that conservatorships must be fraudulent. We made a solemn vow to use any means necessary to spring Michele from her captors.

The plane let down in Columbus after two hearty meals, a catnap, and lots of earnest prayer and discussion. It was midnight.

Determined to save every penny for God, suitcases in hand, we Walked arm in arm two miles down a straight highway to the Holiday Inn. Stiff and formal, I felt like I was enacting American Gothic amidst the hayfields and cricket sounds of the Ohio summer.

I hid outside while Amos rented a single room. Dr. Durst had advised Amos to “be careful,” which, in the puritanical Church doctrine of total chastity before marriage, meant “no compromise” or, practically speaking, two separate bedrooms. But, eager to be frugal, Amos simply prepared a separate bed for me—the tub in the bathroom! We both laughed uncontrollably at the primly propped pillow, delighted we’d “obeyed” Abba without spending the extra cash.

At 5:00 a.m. Sunday we woke for Pledge Service. Together we carried out the Familial Unification Church ritual, chanting our lifelong devotion to God and Moon and our burning antipathy to Satan—who was everyone opposed to Moon.

Honoring the sacrifice Moon had made for us during his imprisonment in North Korean prison camps years ago, we drank orange juice and coffee but couldn’t eat till noon. Amos, in an elaborate and sanctimonious gesture, put sugar and cream in my coffee. To serve another in the Church is the highest honor; inverting usual habits, the server becomes the victor. A cup of coffee or tea offered and taken has cosmic significance.

Amos rented a silver Dodge and we drove to Ohio State University and made ourselves comfortable in the faculty club. Chanting under my breath for a good lead into our puzzle, I sparked up a conversation with what turned out to be the head of the dental school. After hearing my careful story, it developed that he’d graduated from Berkeley and knew the dean of a law school in northern Ohio very well. What a gold mine!

Amos was pleased with God’s effort so far.

After several phone calls, Amos made arrangements to meet with the dean of the law school that night. We knew Munroe Falls, where Michele was being held, was a suburb of Akron. Only two hours’ drive away, we were getting warmer….

The dean of the law school invited us into his orderly office. Calling himself a follower of New Education Development Systems, Amos pleaded Michele’s case. After Amos finished, our dean promised us that his assistant, Dean Reece, who’d handled the Vietnam Calley case, would help us the next day. The dean showed us briefly around his law school, bought us hot chocolates, and offered to let us sleep in sleeping bags in the student lounge. Surprised but grateful, we declined the hearty invitation because we needed to be where we could plan more privately.

Monday morning we charged into the Akron Public Library, fighting crowds of people swarming to see the famed Soap Box Derby, and combed through thousands of feet of microfilm of newspaper and magazine articles about the Alexanders, Michael Trauscht, and deprogramming.

The microfilms led us deeper into espionage and masquerade. We discovered there was an Akron person who conducted deprogramming from a subterranean office in an alley beneath the haunted-looking Brown Derby Hotel. The label on his door read Mind Freedom.

Inside worked a young, slapstick psychologist who claimed he knew everything about the recruitment methods of Hare Krishna, T.M., Scientology, and, worst of all, in his opinion, Unification Church.

We introduced ourselves as Amos and Lael; soon he’d handed me a New Age Magazine article by a journalist named Bob Banner about our own Boonville ranch. I recognized the magazine writer instantly; the article was all about Bob Banner’s experience in my group (and he named me) up on the recruitment farm! I excused myself hastily to go to the bathroom while Amos—unaware—kept presenting himself as a deprogrammer with special expertise in the neurophysiology of brainwashing. Amos, however, was soon handed the article, came across my name, and shortly excused himself, too, to fulfill “other obligations.”

Close call! we breathed, out on the street.

Dean Reece met us that afternoon. A gentle southern hulk of a man, he took in every word of our story and scoured it in his mind. I trusted him at once, but Amos made it clear by several sharp looks that I was not to reveal so much information. Reece himself, a loyal Baptist, said he didn’t care for the deceptions and dubious goals of some of the cults, especially Moon’s army (whom he suspected, despite our circumspection, we had some connection with), but he was concerned for the civil rights of “a woman being held against her will.” He promised that if we could verify Michele’s presence in Joe Alexander’s Munroe Falls house, he would go there accompanied by the local chief of police and talk to her. He recommended we do some sleuthing that night and find out exactly where she was.

Equipped with new Penney’s tennis shoes, a can of chemical eye-spray, and a deafening noisemaker, I stole through the molasses-black woods behind Prentiss Street, while Amos patrolled the pleasant rural neighborhood from the car, its headlights switched off. I’d never spied on a suspected house before, but I was well versed in stealth; flower sellers for the church dare illegal entrances to restaurants, bars, and office buildings, all of which forbid solicitations, from San Diego to Toronto. I prayed to be invisible and for the chorus of neighborhood dogs to stop yelping so suspiciously.

I crept up to the back of what I was sure was the right house and clung to one side of a tree. Finally I dared to look in.

Sure enough, Michele herself sat in the kitchen with a group of people. She looked tired and high-strung, but that was to be expected. After all, she was surrounded by the worst people on earth, the ones God raged against.

Yet, as I watched in fascination, eight ordinary-looking people around the dinner table bowed their heads and prayed. Then everyone laughed and talked companionably as they ate.

I grew more and more outraged. How could they pray, even presuming to address God? How could they pretend to be happy? I remembered Dr. Durst’s lecture: “God and Satan, good and evil, look exactly alike. But one is for world benefit, one is for self-benefit.” Who, the thought flashed in me, dictates or defines world or self-benefit? I let the troublesome wonder escape, seized as I was with the abrupt desire to let Michele know that her saviors had come, that her true Family was nearby, that her captivity was about to end….

Then, through the gold-lit window of the homey kitchen, I watched Michele get up, yawn, stretch, and leave the room with three young people. Eventually I edged across the moonlit lawn on hands and knees, hiding myself in the shadows alongside the back porch in order to eavesdrop on the people who had just entered it. A pair whom I guessed to be the Alexanders were talking with another couple whom I recognized from photographs as Michele’s parents. I studied their faces, earnest and worried; they looked malevolent, plotting….

Then a phone rang. When it did, I recognized my only chance to dart away unnoticed in the flurry of interruption.

Panting, and fearful of discovery, I caught up with Amos’s car and climbed in the window to avoid the noise of the door banging. Amos yelled when I stepped on his hand. I shushed his cry, only to sit down on the noisemaker in my back pocket! The pair of us, unintentional clowns that we were, eased the car through back streets to the main highway.

“Amos, she’s there! I saw her! We’ve got her!” I exulted.

“Is she tied up? Does she look bruised or beaten?” he demanded.

“Mostly just nervous. Out of place,” I replied, more slowly.

“Great, we’ll have her out by tomorrow. The dean’s reliable.

Thank you, Heavenly Father. Let’s pray.” Then, “You hungry, partner?” Amos coaxed.

“Anytime you are, chief,” I joked.

“We haven’t eaten all day. Let’s stop at the Red Barn. You order and I’ll call and give the good news to Onni.”

“Give her my love,” I offered awkwardly.

“I expect she gets all she needs from God,” Amos rebuked me. I felt like Cain, whose offering had been rejected.

After we ate it was midnight, but Amos’s and my night watch wasn’t over. Shortly after Michele had disappeared with her father in San Francisco, Mitch, a responsible Church member, had been seized in a hotel by his uncle and father on a conservatorship order and flown to Ohio to stay with one of the Alexander sons. Amos was intent on recovering Mitch, too, though his loss to the church was considered less disastrous than Michele’s, as she was a top staff member. We roved from one end of Akron to the other blindly searching for every Alexander listed in the phone book. We turned in unsuccessfully at 4:00 a.m. after singing boisterously to keep ourselves awake.

We met Dean Reece at ten sharp in his office the next morning. Amos told him the results of our reconnaissance the night before, filling in more details about my part than I’d supplied him. Reece listened closely, then put in a call to the Monroe Falls chief of police. An appointment was set up an hour from then in the sedate bedroom town.

As we crowded the dean into our rented car, he talked about an episode a month earlier when a boy had come bursting into his office, insisting that he buy some peanuts. Reece, from Georgia, couldn’t refuse, but he fumed to us now about the brazen intrusion. “That was Unification, wasn’t it?” he pressed. “I tell you, that kid acted like a little demigod, as though his work was more earthshaking than any I’d ever heard of.” Amos and I, in silent fraternity, winked at each other. Someday it would all be clear….

The sterile beige police station didn’t offer us much relief from our anxiety. We chanted incessantly in a lifeless cubicle while Reece conferred with the cop. When both insisted on going to the Alexanders’ home without us, Amos rebelled.

“No representation without us. Satan could get into the dean, especially with that policeman beside him. He’s not sympathetic,” Amos muttered to me confidentially.

More conferring.

Amos lost.

But as soon as the two men left, Amos instructed me to stay behind in the jail and pray hard. He was going to take the rented car and park outside the house on Prentiss Street anyway. After all, God had made him Michele’s guardian.

Amos later told me that at the very moment of his arrival, Michele and her mother had driven up from an errand. The dean and chief were with Esther Alexander on the front lawn awaiting their arrival.

Amos had hurled himself out of the car and run toward Michele.

“Michele, Michele, Lael and I are here. Onni and Teresa love you,” Amos shouted.

Instantly Michele turned to Esther, wild-eyed. “Get me away,” she begged. Esther Alexander grabbed Michele’s hand and ran with her into the house.

“Hey, you go back to the police station,” the chief came out on the porch and angrily shouted at Amos. “We told you to stay away.”

In dismay, in anguish, Amos drove back to join me. He didn’t interrupt my chanting nor did he offer any insight. Instead he held his head in his hands and cried for the pain of Michele’s betrayal.

The minutes we waited were merciless; more like light-years.

Dean Reece and the chief finally entered our room, sober-faced. The chief said, “The girl doesn’t want to see you. She says she cares for you both but she plans to stay with the Alexanders. She believes the conservatorship is justified. So do we,” added the chief.

I shot a hard, blazing glance to Amos. “But I thought conservator-ships were a fraud, a setup,” I backed him up.

“What did Michele say about Onni or Teresa?” Amos begged.

“I heard someone say—I can’t remember who—that Teresa has a devil’s mesmerizing ability,” commented the chief; he seemed open to that possibility.

“That’s a lie! They’re the devils!” Amos pounced.

“Now listen here, you’re a nice-looking pair of kids. The woman you claim is being held against her will wants to be there. Something’s fishy,” the chief remarked.

Dean Reece stood, judgelike hands behind his back. “It seems Michele’s undergone an experience called deprogramming. You’ve heard of it, of course….”

“Yes, and that’s exactly why we’re here. They’ve just finished intimidating, maybe even torturing her, ripping God out of her life in hateful cold blood,” Amos exploded in fury. “If Michele doesn’t come back with us, it’s because they’ve planted false, evil fears in her about a life she loved just two weeks ago. They’re the ones doing the brainwashing, can’t you see?”

“Look,” calmed Reece, “she appears to have control of her senses, and although she appreciates what you’re trying to do for her, she’s happy where she is and wants to stay there.”

“What makes you so afraid of deprogramming?” suddenly asked the chief.

Shocked, vulnerable, I waited for Amos to speak up. “Well,” he said, “my faith must be deeper than Michele’s ever was, but all the same, I wouldn’t relish having it threatened in inhuman ways.”

“How do you know it’s inhuman? Michele speaks highly of both the Alexanders and her parents.”

“She must be brainwashed,” I concluded.

“They’ve taken the Messiah out of her life and Satan’s possessed her spirit. She’s no longer responsible,” Amos added.

“Nonetheless, you two had better think pretty hard before you go traipsing all over America trying to uproot people from a situation they prefer to be in,” warned the cop.

“She no longer knows what she wants. She’s captive. Michele can’t be herself,” I spoke up.

“That, my girl, is a very serious accusation. Who are you to go around legislating or determining one preferred reality for another?” Reece moralized.

The policeman jumped on me. “Who told you to do this anyway? Maybe you’re the captive?”

I didn’t care what he said; I knew I was absolutely right. He simply didn’t understand God. How could he know that the final Truth of God had been proclaimed by the Lord of the Second Advent, who was living in New York at this very hour?

“I hope we’re still friends. I expect you’ll hear from this Michele again. She seems like a sweet person, and sincere. Let me take you both to lunch back at the Holiday Inn,” offered Reece. Since we’d been trained never to refuse a gift to a heavenly child, Amos and I accepted. But the meal was pervaded by our stunned silences.

On the phone to Onni before our return to San Francisco, Amos tried to explain Michele’s action. He told me it seemed beyond Onni’s mental capacity to accept. Michele, Onni said, was lost in Satan’s hands. Then Amos surprised me by a more practical note: Onni feared that Michele knew many secrets about the inner operation of the Church and would tell.

We were ordered home immediately. We owed God a thousand repentances; Onni left us with customary guilt.

“Amos,” I summarized on the plane, “one thing I’ve realized through this disappointment is how vicious and deceiving Satan is. Satan turns everything upside down. And God is helpless without our faith. I could never be deprogrammed. God needs me and I love Him too much.”

Two weeks later I finally talked by phone to my parents. Teresa told me my father had called our centers repeatedly trying to find me. I explained to my mother the mission I’d been on; she made little comment about being abandoned on the Washington Street porch when she came to visit.

What I couldn’t tell either my father or mother was that in June, when I’d begged them to come down just once more to a weekend seminar and they refused, I’d gone out and spent two hours in the dark crying under a tree in Lafayette Park.

That evening I’d finally given my mother and father up. I’d prepared never to see them again in my life, if God demanded.

When I’d come in from that heartbreaking darkness, my real parents had irrevocably and eternally become Moon, Hak-Ja Han, Onni, Dr. Durst. As I had been repeatedly taught in the cult, it was they who were my True Parents.

pages 57-60

Barb: In the Unification Church—I Am Reborn

“I would rather be ashes than dust. I would rather that my spark should burn out in a brilliant blaze than that it should be stifled by dry rot. I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in one magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet. The proper function of man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.”

— Joan London, Jack London and His Times: An Unconventional Biography

April 1973-January 1977.

The Unification years meant one essential thing: I was reborn. I experienced myself as a transformed, totally reconstructed person. In the transition period, I died to my old self, Barbara, and became Lael. My new identity was shaped by action, for life in the Church is action. As a new person in a new Family, acting upon new hopes, anxieties, and goals, I began my life for the first time. What was the process of this rebirth?

The seeds were planted when I first named all the love I had experienced in my life, God. But as Barbara, meeting the Unification Family, my love was uncharted and without direction. Through the Unification concept of Truth and God my love found embodiment in an individual, Sun Myung Moon, as a divine object of worship. Reverend Moon offered my life hope, power, and authority. Barbara was forced to die; only Lael would live forever.

Reborn, I was several different persons depending upon my “Heavenly” task. I participated in five major missions or activities: Center Life, Recruitment Workshops, Flower Selling, National Campaign Activities, and Devotion to Moon. In center life, where the new Truth was structured in community, I grew from “infant” to “child” to “parent” as I gained responsibility. In the recruitment workshops, where I learned the theology, I was a “visionary” along with all the other chosen brothers and sisters. As a flower seller, I was a “soldier” for God. As a national campaigner, I was a “crusader.” And in devotion to Sun Myung Moon as my Messiah, I was a “saved” person, who had sinned.