My Brother Joined the UC and Was Murdered in US While Selling Roses

Shūkan Bunshun, July 29, 1993, pages 38-41

Hiroshi Funaki, his younger brother, gives a confessional account

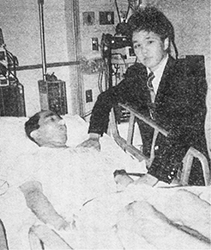

Hiroshi and his mother watching over Atsushi “Junji”

[on an artificial respirator] lying on his deathbed ▼

At the age of nineteen, my brother Atsushi “Junji” Funaki was recruited into the Unification Church after answering a street questionnaire. While living communally with other followers, he completed his schooling. He sold personal seals and peddled fish, then went to the United States. While selling roses on a street corner last year, 1992, he was attacked by two robbers and died of his injuries.

The short, unhappy life and tragic death of Atsushi are revealed here by his younger brother.

My older brother was attacked and killed by two robbers last May in Philadelphia, USA. This happened while he was selling roses on the street as part of the Unification Church’s economic activities.

▲ Hiroshi “Yoji” Funaki at the scene of the attack on his brother

He was 32 years old. My brother’s name is Junji (read “Atsushi”), and mine is Yoji (read “Hiroshi”). We were brothers, three years apart, the only two children of our parents.

This crime was not reported at all in Japan. The culprits have not been caught, and the truth remains unknown.

More than a year later, I have decided to speak out in public about my brother’s death because I have realized that this is not a problem that only our family are grieving over.

I know that there are many people throughout Japan who are suffering because their family members have been taken away by the Unification Church.

Anyone could be involved in a similar incident at any time. I want as many people as possible to know about the reality of the Unification Church’s activities. And I want to prevent such tragedies from ever happening again. I realized that taking action for this purpose is the only way to ensure that my brother’s death, and our tears, were not in vain.

My family consisted of my father, mother, and older brother. In the summer of his fourth year at Osaka Prefectural Industrial College (a five-year program), my brother was invited to visit the Unification Church through a survey done on the street.

That was in 1979, fourteen years ago. Until then, my brother, from my perspective as his younger brother, was serious but he often laughed. He loved kendo and even participated in national tournaments. At that time, his daily routine was to come home by 8 PM and study until around 1 AM. Then, he started not coming home until 12 or 1 AM. When my mother asked him, he said he was “doing volunteer work.” When I asked, “Can you balance this with school?”, the answer he gave was “Yes.”

However, only three months passed before he said he wanted to quit school. His grades were also rapidly declining. When his father became furious, he said, “I’m doing the right thing. Eventually the Soviet Union will invade Hokkaido, and you and Mom will be beaten to death with axes.”

Eventually, my brother left home and began living communally with other members at a Unification Church home while attending school. For our parents, this was likely a compromise to prevent him from dropping out. When I spoke to his classmates, they said, “Funaki-kun is always sleeping during class.” Looking at his diary, it seems he went to bed at 1 AM and woke up at 4 AM to participate in Unification Church activities, so it’s no wonder. During the summer vacation of his fifth year, he went on a mobile team selling specialty foods.

Upon graduation, my brother dedicated himself to the Unification Church, saying, “I’ll regret it for the rest of my life if I don’t do this.” Initially, he evangelized along the Keihan Line in Osaka, and later sold seals in Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture. From November 1983, he started selling fish from a light truck for “Isshin Tenjo.”

What was different about him compared to other members was that wherever he moved, he always kept in touch by phone or letter, letting us know his whereabouts. This was when he was still in Osaka. He contacted my mother asking her to send him 1,000 yen. My mother, worried, went to the home and waited for him at the nearest train station’s ticket gate.

Going out to proselytize with only 400 yen for lunch

When she caught him getting off the train late at night, he said, “Actually, I’m so hungry, I can’t stand it.” She took him to a nearby yakiniku restaurant, and I heard that the way he ate was like a starving child. He said, “I’ve never eaten meat before.” He must have been passing by the yakiniku restaurant with its delicious aroma morning and night, while eating meager meals. When I listened to his story, he said, “When I go out to do missionary work, I only get just enough money for the train fare and 400 yen for lunch every day before I leave the house.”

“400 yen isn’t even enough for an oyakodon (chicken and egg rice bowl). You can only afford something like an egg rice bowl, right?”

“Yeah.”

“Even though it’s so hot, you can’t even buy a can of coffee. What do you do when you get thirsty?”

“I drink water at the park.”

“…Even if you asked me to lend you 1000 yen, you wouldn’t be able to pay it back, would you? What if I just gave it to you?”

My mother said she gave him 2000 yen before they parted ways. I wonder if my brother ever got to eat his fill of yakiniku (grilled meat) in his life after that.

Around that time, he would come home about once every three or four months. He would only stay for a few hours, but when he left, he would take food from the house, like somen noodles or watermelon. He wasn’t going to eat it himself; he said, “I’m going to sell it to the old ladies near the home.”

My father said he often thought, “Should I push him down the stairs? If he broke a leg or something and had to be hospitalized…”

He worked at “Isshin Tenjo” in Yokohama, and then in Suginami. My brother, who knew nothing about fish, was asked by a customer, “What’s in season right now?” and reportedly replied, “What does ‘in season’ mean?”

Even so, he must have worked hard. He became the top salesperson and received a commemorative album, and, presumably at the direction of the church, he also obtained a chef’s license.

In August 1986, my brother went to America. With his chef’s license he began working as a cook in a Japanese restaurant run by the Unification Church.

Six years later, without ever returning to Japan, my brother passed away.

According to my mother, his desire to work overseas had been a dream since childhood. She said that during his junior high school years, he even talked about wanting to join the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers.

His plan was to stay in America for only two years. He moved between restaurants in Jacksonville, Florida; Columbia, South Carolina; East Maynard, North Carolina; and Washington D.C.

His life as a Unification Church member wasn’t as harsh as it had been in Japan, and he even had time to enjoy activities like fishing. He was called by the nickname “Joey,” and seemed to be enjoying his life in America. His cooking skills were also recognized, and he was even offered the opportunity to run his own restaurant by a regular American customer.

Even so, he intended to return home after two years and had even booked a flight. However, his luggage from home was delayed, and he missed his flight. Then, he received instructions to help out at a different restaurant, and so he continued working.

After moving along the East Coast, including Richmond, Virginia; Columbia, South Carolina; Charleston, West Virginia; and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, he finally arrived at his last workplace, the Japanese restaurant “Sonobana” in the New Yorker Hotel in New York.

He was married but the couple never lived together

During this time, in 1988 or 89, he participated in a mass wedding ceremony. His partner was Ms. K, who lived in Tokyo and was four years younger than him. Because our parents refused his request for money transfers, my brother couldn’t fly to Seoul, and Ms. K attended the ceremony alone with a picture of him. Two years later, Ms. K visited my brother in America for about a week.

Ultimately, the two never lived together, and their married life consisted entirely of that one week.

My brother intended to obtain permanent residency in the United States. Last June, he was planning to return home for those procedures. The incident happened a month before that.

On May 10th, my brother went to Philadelphia with two other church members, Mr. A and Mr. B, to sell roses from their car.

The three of them separated to sell the roses. Around 7 PM, when Mr. A went to pick him up in the car, my brother was in the middle of cleaning up.

Mr. A, who had gone to use the restroom at the Kentucky Fried Chicken across from the scene, came out a few minutes later to find an ambulance there, and my brother receiving first aid. According to witnesses, two young black men suddenly struck my brother on the head from behind with a metal rod, and then stripped him of everything he had, from his watch and earnings to his driver’s license.

[The police did not understand how the Unification Church could send a person with money to such a dangerous area in East Philadelphia on their own. The police said that they themselves only went to that area in pairs. They also wondered how a person with poor English could explain themselves to any attacker.]

He was immediately taken to the University of Pennsylvania Hospital. Since he had no belongings and his identity was unknown, the temporary name given to my brother was “Joey.” Strangely enough, he was called “Joey,” the same nickname he used during his time in America. When he was brought in, he was already unconscious. However, he seemed to have said something. But since it was in Japanese, the doctor later regretted not understanding what he said.

The first news of the incident reached our home in Osaka twelve hours later, around 9 PM on the 11th, Japan time. It was a phone call from Mr. B: “Atsushi was beaten by two American men and is in the hospital.” At this point, we didn’t yet understand the seriousness of the situation.

A while later, there was another phone call: “He has a brain hemorrhage and is undergoing surgery to drain the blood.” At this point, the family turned pale. At 1 AM, the third phone call came. “He is now in a critical condition, so we need you to come immediately.”

The morning of the day the incident happened, I had a dream. It was a dream of hiking. As I was walking through a meadow, a man collapsed, having a seizure. An ambulance arrived, and they were about to give him an injection. They said it was an injection to euthanize him. I shouted, “We don’t even know if he’s going to die yet, so what are you doing?!” That was the dream I had.

The next morning, we began preparing for our trip to the United States. The Unification Church handled all the arrangements for the flights and accommodation. My father had to stay in Osaka for work, so my mother and I met up with Ms. K at Narita Airport. On the evening of the 13th, when we arrived in New York, we went straight to the hospital.

▲ Hiroshi watching over his brother Atsushi “Junji” in hospital.

My brother, his head shaved and lying like a mannequin, was undergoing treatment to keep the blood flowing to his brain by accelerating his breathing. Because of his rapid breathing, his body was bouncing on the bed. It was exactly like the convulsive movements of the man I had seen in my dream.

This was my first reunion with my brother in six years.

Mr. B, a church member, acted as our interpreter. The attending physician explained, “The damage to his head is extensive, and he has lost almost all functions except for breathing. There is absolutely no possibility of recovery. We have done everything we can to save this young life, but it is almost hopeless.”

On the 15th, we were forced to make a decision.

The physician said, “Currently, he is being kept alive through medication. From now on, side effects from the medication will appear, and we will have to administer different medications to suppress those side effects. Of course, we will prioritize the family’s wishes, but from a humanitarian standpoint, please consider removing the ventilator and allowing him to pass away peacefully.”

With Ms. K also present, we replied, “Please give us a day to think about it.” After discussing it, the next day, we had the artificial respirator disconnected. My brother’s eyes were slightly open and quickly dried out, so the nurses occasionally put eye drops in them. My mother, unaware of this, looked at my brother’s eyes, which were moist as if overflowing with tears, and murmured, “I wonder if Atsushi is crying.”

A Styrofoam cooler used as a refrigerator

On the seventeenth, we went to the New Yorker Hotel where my brother had been staying and sorted through his belongings.

Despite having been in America for six years, my brother’s belongings were astonishingly few. Many of the clothes were ones I had worn before, and there were holes in his pajamas. In the corner of the room was a single-person rice cooker that looked like a plastic toy. Beside it were two cups filled with water inside a Styrofoam box, along with a partially eaten piece of bread and a mandarin orange beginning to spoil. It took me some time to realize that this was meant to be a makeshift refrigerator. The water was melted ice, and that was probably why the mandarin had gone bad.

At 9:16 p.m. that night, my older brother, Atsushi, passed away. It had been thirteen years since he left home after joining the Unification Church, and that improvised refrigerator seemed to symbolize his entire life.

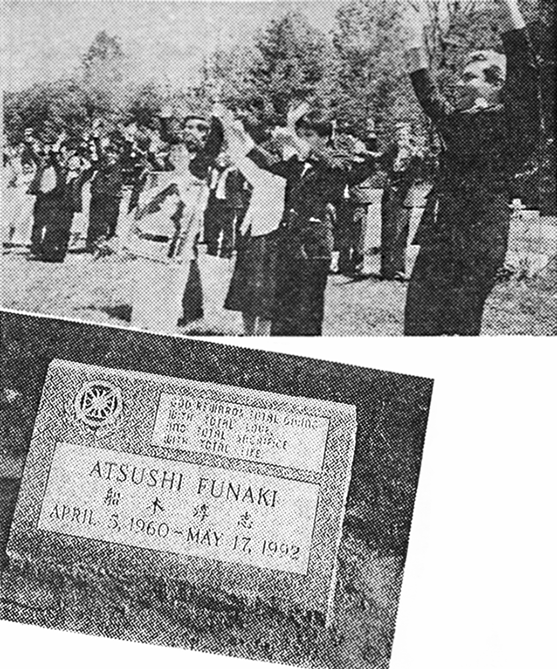

The next day there was a police autopsy. On the nineteenth came the funeral conducted by the Unification Church. It was called a “Seonghwa Ceremony” and a “Wondae Ceremony.” The way the funeral was carried out, and even the decision to bury him in a New York cemetery, were all done exactly as the Unification Church insisted.

▲ The Unification Church-style funeral and Atsushi’s grave

They say that being called up to heaven is the beginning of a new journey, so men wore white ties and women wore clothes adorned with red carnations, and at the burial everyone raised both hands and shouted “mansei” (“long live” literally “ten thousand years”) three times. If that was their way, there was nothing to be done about it. But why were my mother’s and my wish to at least bring him back to Japan ignored? All we were allowed to take back to Japan were a small lock of his hair and his fingernails. [The mother and brother were very upset about the funeral service.]

After returning to Japan, on the twenty-fourth, a “Seongcheon Prayer Meeting” was held at the Abeno Church in Osaka. Even though relatives from our family gathered, it was conducted in a very high-handed manner. At that time, the woman known as his “spiritual parent,” who had first recruited my brother through a street questionnaire, came and greeted my father and me. When I later told my mother about it, she scolded me, saying, “Why didn’t you tell me! I would have slapped her across the face once or twice.”

What I cannot tolerate about the Unification Church’s way of doing things is not limited to how the ceremonies were handled.

In early June, the church’s general affairs director, the vice chairman of the Abeno Church, and a person carrying a business card that read “Family Education Consultant” came to our house. When my mother asked, “The death certificate says, ‘involved in an incident while working.’ Doesn’t workers’ compensation apply?” the consultant—who was not even a member of the Unification Church—said, “It was an accident that occurred during religious activities.”

Even now, I cannot understand in what capacity he visited our home, or what authority he had to make such a statement. When we asked, “What about health insurance and pension?” a representative from the Unification Church’s U.S. office who visited later replied, “Young members are not enrolled in insurance or pension plans.”

In the end, the Unification Church provided only a little over two million yen as condolence money. Their irresponsibility was such that, at one point, we even considered filing a lawsuit for damages.

Why is this not reported in Japan?

But now that a year has passed, the issue of money no longer matters. What our family wants first and foremost is to bring my brother’s body back to Japan.

Next, we want to know the truth about what happened. We were told by a local church member that “an open investigation is being conducted on television,” but is that really true? If it is, how is it progressing?

When it comes to uncovering the truth, why did it take as long as twelve hours from the time the incident occurred until our family was contacted? According to what Mr. A said, my brother was surrounded by paramedics and no one could get close to him, and it took time to find out which hospital he had been taken to.

But if they were truly friends, wouldn’t they have pushed through the crowd, approached him, identified themselves by saying, “He’s my friend,” and ridden along in the ambulance?

The insistence on burying him in the United States, too, makes it impossible for me not to sense an intention on the part of the Unification Church to keep the matter from becoming public. Looking back now, our understanding of the true nature of the Unification Church at the time was still very shallow. That is deeply regrettable.

Why, moreover, was this incident not reported in Japan? Even when we contacted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, my brother’s name was not included among Japanese nationals who had died overseas.

What I want to appeal through the media is the misery and danger of the lives led by members of the Unification Church. I want even those who do not have a believer in their family to know about the realities described here.

Even now, I have dreams. Recently, I had one like this: my brother calls me on the phone.

“I’m at Osaka Airport right now. Come and pick me up in a car.”

When I open the second-floor window, my brother, who had said to come get him, is walking toward the house. When I let him into the room, he happily talks about America. Then he says, “I’ll clean a fish in the kitchen for you. I’m good at it,” and stands up. At that moment, I suddenly come to myself and think, “But my brother is supposed to be dead.” Then my brother’s face takes on a lonely expression, and before long his features blur and fade away.

It’s painful to relive these memories, and the helplessness of our family is heartbreaking. But it is so that my brother’s death will not have been in vain [that I have decided to speak out in public]. We earnestly hope that you will understand this reality.